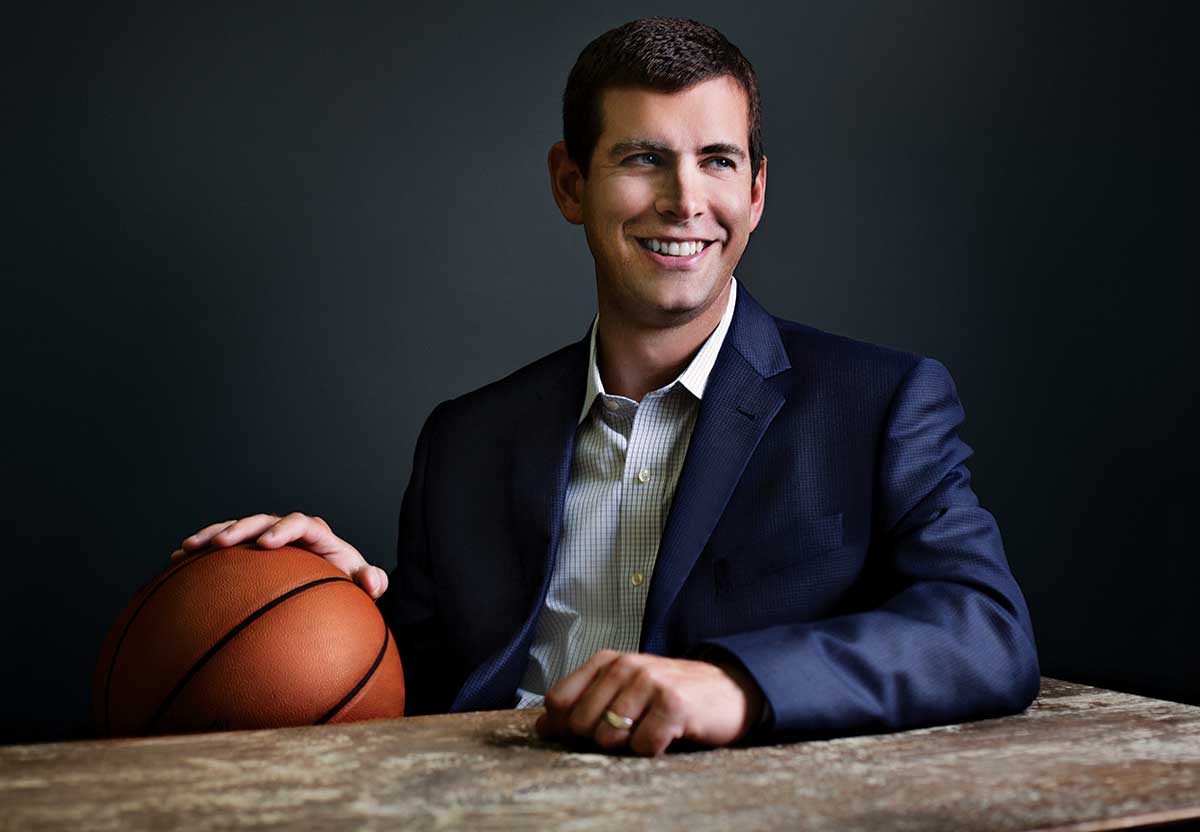

Can Coach Brad Stevens Put the Celtics Together Again?

Photograph by Trevor Reid

It’s Saturday night in Las Vegas, and the NBA Summer League is in full tilt. There’s none of the pomp of the regular season—that’s the appeal of this brief showcase—but the Thomas & Mack Center, on the UNLV campus, is still packed with well-known faces. Hall of Famer Dominique Wilkins is standing at the entrance. Former All-Star and current Milwaukee coach Jason Kidd patrols the baseline. Mavericks owner Mark Cuban is courtside.

The pavilion’s setup is so intimate—it’s essentially a high school gym decked out with a pair of HD video boards—that the only thing separating the coaches and scouts from the fanboys and autograph hounds is a thin line of police tape, cordoning off a small section of reserved seats.

Summer League is a chance for NBA teams to evaluate young talent, and on the court tonight are the Celtics’ rookies, second-year hopefuls, and undrafted free agents. There’s just one twist: This ragtag group of inexperienced unknowns might as well be Boston’s 2015–2016 opening-night roster. Three years removed from the Big Three era—Ray Allen departed in 2012, Kevin Garnett and Paul Pierce in 2013, Rajon Rondo last year—the Celtics have the fewest marquee players of any major Boston sports franchise. None, in fact. Instead, the most recognizable Celtics brand name is, on this Saturday night, sitting in the lightly policed VIP section with his son. Four rows up, seated amid the easily identifiable NBA professionals talking on their phones and taking notes in their team-issued polo shirts, the man and his son are recognizable only for their utter banality: The boy is decked out in Boston green and white, glued to his team at the edge of his seat, while his father tries to strike up a conversation with a man sitting beside him.

The pair’s presence seems so out of place that it catches the attention of an usher, who approaches the dad and asks to see his team credentials. The father doesn’t seem surprised. He calmly lifts the plastic tag at the end of his lanyard to show the usher: “Brad Stevens. Boston Celtics.”

It’s hard to imagine Doc Rivers or Phil Jackson or even Golden State’s Steve Kerr getting carded at an NBA venue—and certainly not without a flash of annoyance or fluster of indignity. But Stevens takes it as a matter of course. Not getting recognized happens to him almost every day, and not just on the road. It happens when he’s boarding a plane at Logan, out with his family near their home in Wellesley, even grabbing a bite around the Garden smack in the middle of Celts-crazy Boston. Rare is the day that passes without the slender, 6-foot-1 coach going unrecognized. “I don’t think I’m overly recognizable,” he’ll say, running his hand over his clean-shaven cheekbones.

This could be a problem. If the ushers don’t recognize your head coach—the man team president of basketball operations Danny Ainge has handpicked to whittle a band of young unknowns into NBA playoff contenders—then it’s a good bet he’s not famous enough to put on the cover of the media guide. And if not Brad Stevens, then who?

It’s not just Stevens’s face that blends into the scenery. His whole approach to coaching is based on deflecting attention. He hardly ever yells at his players, doesn’t stomp and carry on from the sideline. The only time he talks about himself is when he’s assuming blame for the mistakes and subpar play of his crew of misfits. It’s precisely the meek and humble demeanor you’d expect of a former Division III point guard and coach from a tiny private college in Indiana dropped into a locker room of NBA-size egos. “In college, you’re coaching young men who haven’t accomplished anything, and they have to adapt to you, mostly,” says Stevens’s friend Mike Krzyzewski, the iconic Coach K who has won five NCAA championships at Duke, and guided two pro-stocked U.S. national teams to Olympic gold. “Professional athletes are men—that’s what they do. If you’re smart, you’ll adapt to them.”

So far, Stevens’s adaptation has yielded a combined 99 regular-season losses in two years. To be sure, this Celtics team is a rebuild. Everybody understands this. And everyone acknowledges that in the midst of the carnage, Stevens has been able to carve out a few symbolic victories. Last year, he engineered a late-season hot streak—overcoming a flurry of personnel shifts, including Rondo’s departure, by deploying his tireless preparation and vast basketball IQ—and led the Celtics on a spirited 20–11 run to sneak into the Eastern Conference playoffs. It was impressive, but only to a point. If there was any faint hope that Stevens’s shoddy Celtics could compete with playoff-caliber NBA talent, it was wiped out when LeBron James and the actual stars of the Cleveland Cavaliers dispensed with Boston in four straight games and sent them home.

As Stevens leans back into his seat in Vegas, he’s looking at a bench of players who cannot win it all. If Boston is ever going to regain a legitimate place at the playoff-season party, it’s going to need superstars—and a coach who can command and control them. Young players eager to make their mark on the league, at bargain-basement prices? Mid-level talent looking to impress a true contender and jockey for a trade? These are the guys who will play their hearts out for Brad Stevens—which makes Ainge a genius and Stevens the perfect man for the moment. But what’s the long-term play? Teams tend to take on the personalities of their leaders. Phil Jackson was the mystic Zen master. Pat Riley was the firebrand; Gregg Popovich, the grizzled yeoman. Can Stevens’s everyman routine provide the energy it’s going to take to win banner number 18? Or is he just a stunt driver, taking the bumps and keeping the seat warm while Ainge pieces together a championship machine—and then hires a bigger name to drive it across the finish line?

Photograph by Trevor Reid

Talk to Stevens now, and you’ll hear platitudes about selflessness and team play. It wasn’t always that way. In his childhood imagination, Stevens was the one with the ball as the game clock expired at Assembly Hall, home of coach Bob Knight’s Indiana University Hoosiers. In the floodlights of his parents’ suburban Indiana driveway, he’d coordinate daylong pickup games with neighborhood kids. In the unfinished part of his parents’ basement, the only child dribbled around chairs while watching worn-out videos of IU games. He wasn’t dreaming of exerting his egoless mentorship from the sideline. The young Brad Stevens had his heart set on basketball stardom.

By the time Stevens finally stepped onto the hardwood, on a fifth-grade AAU team, he was running the game as a small guard who was more interested in shooting than dishing to teammates. “He couldn’t play a lick of defense,” says Brian Flickinger, a friend and teammate since they were seven. “But he tried. He tried hard.”

When the shot didn’t fall or the final score wasn’t in his favor, Stevens anguished. While other kids were going out for postgame milkshakes, he stayed behind and practiced in an empty gym. His father, an orthopedic surgeon who had played football at IU, and his mother, a college lecturer, often found themselves at a loss to console him. It wasn’t simply competitiveness. “I grew up with a maybe healthy—maybe a little unhealthy—fear of failure,” Stevens says. When Stevens’s ability and preparation weren’t quite enough to prevail, he was not above trying to find other ways to beat you. “He comes off as a squeaky-clean guy, but he’ll take advantage,” Flickinger says. “Not cheating. But he can read people.”

That ruthless streak served Stevens well at Zionsville Community High School, where he set the school record for career scoring, assists, steals, and three-pointers, and the team went to two Indiana State Sectional finals in his three seasons as a starter. In Stevens’s senior year, he led the state in scoring during sectional play and was named sectional MVP.

But Bob Knight never called. Stevens was a bit undersized, a bit too slow. Instead, he accepted a scholarship to DePauw, a Division III liberal arts school where he would be able to play right away. Sure enough, Stevens immediately shot his way to all-conference honors.

The team, however, was winning only about half its games. After the Tigers stumbled out of the gate in Stevens’s junior season, coach Bill Fenlon decided it was time to give more minutes to a new crop of underclassmen. Suddenly, Stevens the star was watching from the bench. “He struggled with that a lot,” says his wife, Tracy, a fellow DePauw student who was dating him at the time. “I remember staying up late and having very long conversations about it.” Classmate Josh Burch was beside Stevens on the sideline. “We had to make a choice,” he says. “Put our ego in front of our team, or be leaders and put our team before ourselves.”

At first, Stevens chose ego. During one practice, Burch remembers that along with Stevens, he and the other upperclassmen took it to the rookies in a scrimmage, even talking a little smack along the way. “We kicked their butts,” Burch says. “We were feeling pretty good about ourselves, like we had proved that we deserved more playing time.” Coach Fenlon disagreed and pulled his team captains aside after practice. “I told them that these kids needed mentors to make some sacrifices, not to freeze them out,” Fenlon says. “You have to accept your role, whatever it is. You don’t necessarily have to like it, but if you can’t accept it, you’re just a shitty teammate. Everybody’s got an ego. We’re all me-first to an extent. But when you’re on a team, it can’t just be me first.”

That wisdom didn’t sink in immediately for Stevens. In fact, at the time, he considered quitting. For the first time in his life, his personal basketball glory and his team’s success were not on parallel paths. On the contrary, they now seemed at odds. It had been plain to Stevens for some time that he might not be destined to knock down the winning shot at the Final Four. Until now he thought he’d have two more years in the spotlight to keep the dream alive. And yet to walk away now would be to admit the ultimate failure—something Stevens was not capable of doing. So he stayed, and took a back seat.

In Stevens’s last two seasons at DePauw, Fenlon remembers that Stevens said all the right things, continued to work in practice and contribute when called upon, and went through the motions of being a good teammate. But Stevens admits he was never comfortable in his reduced role. He graduated in the spring of 1999 with a degree in economics and traded his failed dream for a job as a marketing associate at Eli Lilly, the multi-billion-dollar pharmaceutical company. His basketball career was effectively over.