Joe Gibbons, the Bank-Robbing Filmmaker

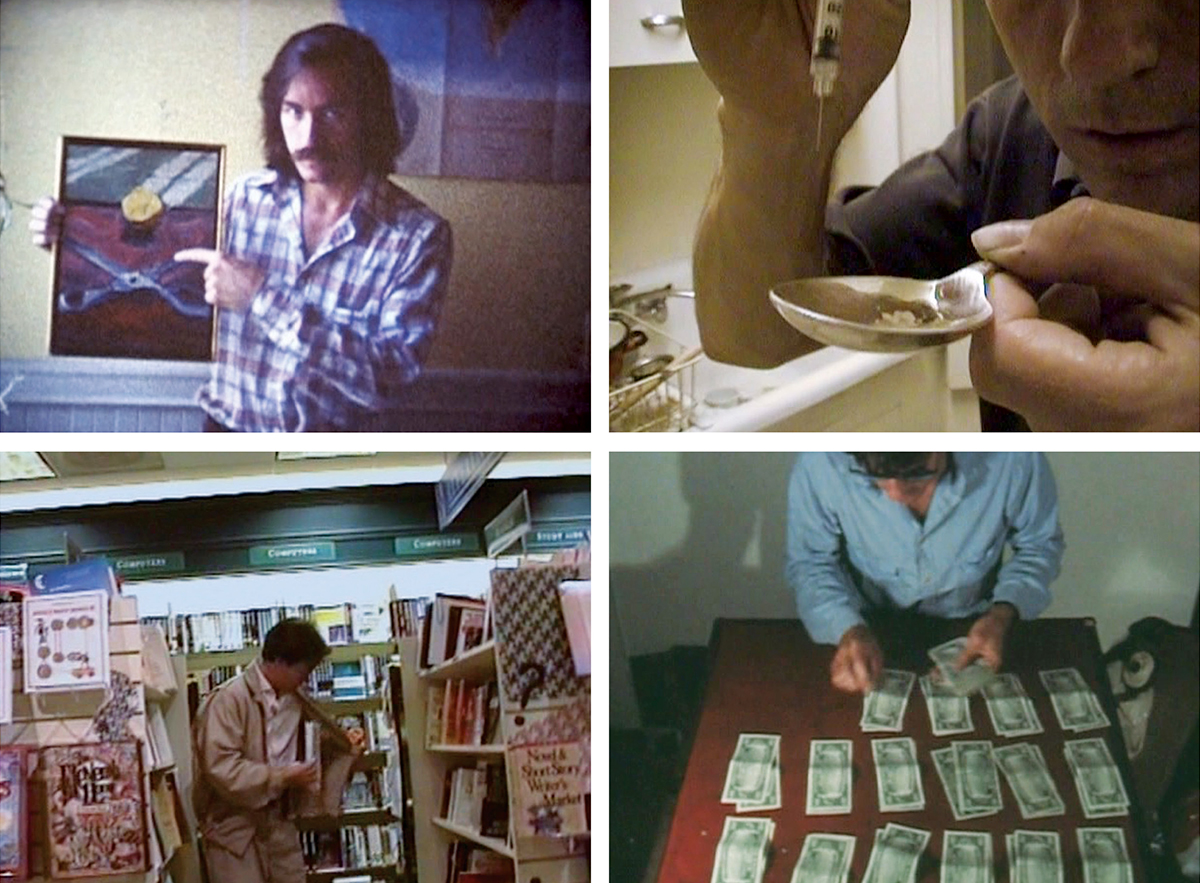

A Filmmaker’s Confessions: In Joe Gibbons’s critically acclaimed 2001 film Confessions of a Sociopath, the filmmaker brags about stealing Richard Diebenkorn’s painting Scissors and Lemon, shoplifts from a bookstore, shoots heroin, and talks about selling stolen books for money. / Surveillance footage courtesy of New York City Police Department; courtesy of Providence Police Department

But there was another side to his life in those decades, running parallel to the films he was making. Gibbons talks about that darker side on camera in his friend Saul Levine’s film series Driven (Boston After Dark). Shot in 2002 from the passenger seat of Gibbons’s car, Driven shows him driving around Boston and Cambridge, reminiscing about a time when a starving artist could still afford to live in the Back Bay and on Beacon Hill. He passes his first Boston address, a former rooming house on Beacon Street, and his next home, on Joy Street near the State House. At times, Gibbons’s tour of Boston in Driven becomes a petty-crime tour, as he confesses to shoplifting more books and champagne from local stores. Around Harvard Square, he drives past several bookstores he says he can’t go back to.

“In all his work, including my Driven, when he’s talking, there’s always a line between fiction and truth,” Levine says. “He’s always somewhat of a character. In Driven, he’s as much enacting a narcissistic personality disorder. He’s not necessarily saying he has one.”

In later films, though, Gibbons played up that ambiguity—especially in his 2001 opus Confessions of a Sociopath. In it, Gibbons often addresses the camera, confiding his subversive thoughts to the audience. Gibbons’s actual therapist appears on screen, but Gibbons also plays the part of a therapist in voice-over narration. “He is enormously preoccupied with himself and the image that he conveys to others,” Gibbons-as-narrator says about himself, as the footage fades to show a medical form listing diagnoses of narcissistic personality disorder and opioid abuse. Gibbons has said he used his real medical records from McLean in the film.

Using footage he shot during different eras of his life, Gibbons shows himself shooting heroin as the camera watches, telling the viewer he steals and resells books to make money, piling up books in his apartment, and slipping a book into his pants in a bookstore. Most of the footage seems to be from the 1980s, but some seems disconcertingly recent, shot on crisp video. On screen, Gibbons retells the story of his art theft in Oakland, and confides to the camera that he hopes his probation officer in Massachusetts doesn’t find out about his other probation in Rhode Island. The camera pans across what appear to be court papers from Providence in 1984—according to the Providence police, Gibbons was in fact convicted of larceny there that year. Rhode Island court records also show that Gibbons pleaded no contest in 1992 to shoplifting a $69 book about artist Fernando Botero and the $59.95 International Design Yearbook from the Brown University bookstore. He got six months’ probation.

Confessions, named in critics’ best-films-of-the-year lists in Artforum and Film Comment, cemented Gibbons’s reputation as an avant-garde comedian and auteur. “Mr. Gibbons’s persona, if not his actual personality, is at once guileless and entirely untrustworthy,” wrote New York Times critic A. O. Scott, “as if the distinction between lying and telling the truth had never occurred to him.”

Friends noticed the same ambiguity in Gibbons when he was off camera. “It’s like performing, but not performing,” says MassArt’s associate director of video, Joe Briganti, who got to know Gibbons when he was living in Jamaica Plain in the ’90s. “It was hard for me to tell if that was just the way he is. It seemed to never turn off.”

In his mid-forties, Gibbons settled down, as much as someone like him could. Handsome and funny, he’d had a lot of girlfriends. But in the late ’90s, he got into his longest relationship, with Louise Bourque, a French-Canadian filmmaker who was teaching film in Boston. They moved into a duplex in Malden together.

In 2001, Gibbons finished Confessions of a Sociopath, and won a Guggenheim Fellowship and a $12,500 grant from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Soon after, he got his steadiest job ever, joining MIT’s Art, Culture, and Technology program as a full-time lecturer. “This is where I teach,” Gibbons says on camera as he drives past MIT in Driven. “A lot of places ask me never to come back, but they’ve asked me to come back in the fall.”

Friends recall the job as a turning point for Gibbons. “He was living on the edge, running from debt collectors,” Levine says. Then, at MIT, “he had a decent day job and didn’t have to steal books to eat.”

Gibbons knew the job wouldn’t last forever. MIT normally limits lecturer appointments to three years, but Gibbons’s department head renewed his appointment, and he stayed for almost a decade. He became a popular teacher. Students stressed out by their high-pressure classes found his video-editing and visual-arts classrooms a refuge. Direct but not judgmental, Gibbons encouraged them to take risks in their work, and sometimes counseled students through family problems or breakups, says Benjamin Gerdes, his teaching assistant in 2006. “He was visibly not always comfortable in front of a class,” Gerdes recalls, “but also polite, charming, and endearing at times.” Students liked his edgy sense of humor, even if it caused awkward moments. Once, Michel Gondry, the prominent French filmmaker, visited Gibbons’s class and saw a student sleeping. “We shouldn’t have given him all those drugs,” Gibbons deadpanned. Gondry thought Gibbons was serious.

By the 2000s, Gibbons was a fixture of Boston’s film and art-gallery scenes. An experimental film and video series at the Coolidge Corner Theatre often showed his films. The Institute of Contemporary Art included a Gibbons film in its opening-night program when it moved to the Seaport in 2006. The next year, Gibbons collaborated with fellow MIT art instructor Joe Zane on two gallery shows at Allston Skirt Gallery, titled “Pull My Finger” and “Joe.” The shows included videos, a fake kit labeled “How to Become an Artist,” and a bilingual spoof edition of the German art journal Parkett with Gibbons on the cover, in an ’80s film still, brandishing a gun.

Gibbons made his film-panel talks into a sort of performance art. Robert Todd, a filmmaker and Emerson College associate professor, once shared a stage with him and indie-film director Hal Hartley. An audience member asked Hartley how he funded and produced his films, and after Hartley answered, Gibbons spoke up. “He went on this whole thing about hiring a crew, how expensive it was,” Todd recalls. Gibbons, who still made films with just himself and a small camera, was cracking a long joke about underground film’s do-it-yourself isolation from Hollywood. “He never broke a smile.”

Gibbons’s essential weirdness never quite receded. In 2003, Anjali Gupta, a writer for the San Antonio alt weekly Current, interviewed Gibbons and expressed surprise over his success at getting grant funding for Confessions of a Sociopath. “So how does he solicit money to make an autobiographical film about being an antisocial kleptomaniac junkie facing multiple prison terms?” Gupta wrote.

“I do quite like the irony in that,” Gibbons responded. “I guess I do sometimes successfully downplay the element of reality in my work.”

In 2010, after eight years, Gibbons left MIT. His former supervisor says he departed on good terms after his contract expired. But leaving MIT seemed to destabilize Gibbons. Without the job, he seemed to lose his footing. He began to fall.

Craig Baldwin, his friend from San Francisco, visited Gibbons about five years ago and found his Malden home a mess. Both sides of the duplex’s central hallway were lined with expensive art books. Super 8 reels were piled 5 feet high in one room. Gibbons, who’d declared his intention to make a sequel to Confessions of a Sociopath, was constantly cutting new versions of his old footage. Baldwin figured part two was in that mountain of reels. “It was insane, out of control,” Baldwin says. “He was addicted to film—like he was addicted to everything else, I guess.”

The sequel remains unfinished. Gibbons’s artistic output slowed to a trickle of minimalist, one-take shorts. The abstract film Driving/Rain from 2010, likely shot with a cell-phone camera, focuses on the sound of rain and visuals of pretty, multicolored lights blurred in a watery car window. In The Florist, a disturbing satire of emotionally tortured relationships, Gibbons talks to a bouquet of flowers, growing angrier and more envious of their beauty. Then he destroys them with scissors, a knife, and his bare hands. “Why can’t you just love me?” he shouts at one flower before eating it.

Gibbons’s friends in Boston saw less and less of him. Levine thinks he went to Canada with Bourque for a while and stayed with friends in New York State. At some point, Gibbons and Bourque broke up. (Bourque did not respond to Boston’s request for an interview.) Friends say the relationship’s end left him even more adrift.

Karen Finley last saw Gibbons in the summer of 2014, for her “Artists Anonymous” series at the Museum of Arts and Design, in New York City, in which Gibbons and artists talked, 12-step-style, about their addictions to art. Levine says Gibbons couch-surfed at various friends’ homes, but fell out with some of his hosts. In late 2014, Bourque sent out an email asking friends to help Gibbons. Levine says Gibbons emailed him asking to stay with him, but he decided against it because his girlfriend was scared to take Gibbons in.

Last November 18, according to Gibbons’s confession to New York City police, he woke up at a friend’s apartment in Providence and was reminded that he had to find another place to stay. Gibbons considered going to a homeless shelter or telling emergency-room doctors he was thinking of suicide. (It’s not clear whether Gibbons was serious, or just strategizing about how to get a roof over his head.)

To quell his anxiety, Gibbons wrote, he popped an Ambien and drank several Pabst Blue Ribbons. Then he walked to downtown Providence. A bit after 2 p.m., he looked into the window of the Citizens Bank on Westminster Street, then stepped into the bank and got in line.

“At some point I wrote a ‘demand note’ on a withdrawal slip,” Gibbons wrote. “When it came to be my turn, I approached the female teller with great trepidation.…For some reason, I told her the money was ‘for the church.’ I tried not to be intimidating, and thanked her for her cooperation, and apologized for the interruption.” She handed him $2,950.

Gibbons had read somewhere that robbers should shed their outfits as soon as possible. So after slipping out a side exit, he threw his red bubble jacket in a dumpster. He went to the Providence library, where he checked the cash for tracking devices and found none. The Ambien wore off and the weight of what he had done sank in. Anxious again, he found a bar and had several drinks. Then he called several people and confessed to them. None of them turned him in.

Captain Michael Correia, of the Providence police, says the silver-haired man caught on the bank’s security camera seemed like an unusual robber from the start.

“‘Thank you, this is for the church’—that’s not a common theme in bank-robbery notes,” Correia says. These days, he adds, bank robbers tend to be the downtown homeless, down-and-out people addicted to drugs or alcohol. “This guy seemed to be an outlier,” Correia says. “One of the detectives mentioned he seemed to be well dressed. He didn’t seem to be a drug addict. We were thinking maybe he had a gambling issue.”

Gibbons traveled from Providence to New York City, probably living off the stolen $2,950 for about six weeks. His first stop in New York was to see his psychiatrist, to replace an expired prescription for the antidepressant Effexor, he wrote in his confession. With his 62nd birthday seven months away, Gibbons also filed for Social Security.

In his confession, Gibbons portrays himself as drunk and spaced out on pills on December 31, the day of the New York City robbery. “I checked out [of] my room at the Bowery Grand and, not knowing what to do or where to go, took the only sedative I had—Ambien—and finished the bottle of Sutter Home Moscato wine from the night before,” he wrote. He walked around the neighborhood, waiting for the Ambien to kick in, then decided he couldn’t wait. “I took 30 mg of Adderall, hoping irrationally to focus my thinking. I remember recording some street scenes with my Kodak video camera. After that, my memory goes blank.” Somewhere in that blank spot, he turned on his camera and asked it if he should really rob another bank.

After his arrest, Gibbons’s friends debated whether his bank robbery with a video camera was an act of art, or an act of desperation. Karen Finley and Saul Levine say Gibbons’s filmed heist reminds them of the late Boston-born artist Chris Burden’s performance Shoot, from 1971, in which Burden let a friend shoot him in the arm with a .22 rifle. Finley calls Gibbons’s bank-robbing “very dangerous” to himself and others, but she notes that artists have sometimes responded to crisis, or to moments in history and culture, with acts of shock and danger. “That’s about subversion or interrupting what we’re seeing,” Finley says, “for us to relook at what we’re doing as a society.”

Levine sees the bank robbery as “a cry for help”—but also as part of Gibbons’s body of work. “The bank-robbery shot is kind of a money shot for an autobiographical, transgressive film about the dilemmas of being the marginal artist in America,” he says. It’s a dilemma that avant-garde filmmakers such as Gibbons and Levine know well. “I’ve been making films for fucking 50 years,” notes Levine, a MassArt professor who runs the MassArt Film Society’s Wednesday night screenings, “and you’re one of the first reporters in Boston to talk to me, and you’re not even talking about my work.”

In interviews before and after his bank-robbing, Gibbons said he was long influenced by Arthur Rimbaud, the famously decadent French poet who believed an artist “makes himself a seer” when he “exhausts all poisons in himself,” becomes “the great patient, the great criminal, the one accursed,” and “reaches the unknown.” But Levine points out that Rimbaud wrote that manifesto at age 16.

“Joe always lived on the edge,” Levine says. “When you live on the edge when you’re 20 or 30, it’s different than when you’re on the edge when you’re 61.”

In June, Gibbons pleaded guilty to the Manhattan robbery in exchange for a sentence of one year in jail. He and his Legal Aid lawyer never tried to use an art-making motive as a defense in court.

Two dozen former students and colleagues wrote the judge as character witnesses in support of Gibbons. Only one, former MIT instructor Julia Scher, argued that artistic intent should be a mitigating factor in the robbery. “I hope you cast your eye upon him favorably and not imprison him,” Scher wrote. “I am confident he meant only the best for his art.” Reached in Germany, where she now teaches, Scher said she didn’t want to comment further because of a backlash against her letter in the press and on art blogs.

Gibbons’s New York sentence was shortened to eight months with credit for time served and good behavior. On September 8, the day his sentence ended, the filmmaker who called his one-man video-editing company Fugitive Productions was arrested on a fugitive-from-justice warrant. He was extradited to Rhode Island two weeks later.

In Providence’s district court, jailed defendants make their first appearance in pairs, chained together. On September 28, Gibbons, dressed in prison blue over a gray T-shirt, stood before the judge, his handcuffs linked to those of a bald man in studded black jeans and a sleeveless Everlast hoodie. Gibbons’s chain mate went first. He was charged with drug possession with intent to distribute; a police inspector told the judge he was caught in a drug raid, standing over a flushing toilet with a plastic baggie in his hand. Then, it was Gibbons’s turn. He was charged with second-degree robbery—theft by threat, without a weapon. Gibbons asked for a public defender. He made bail on October 5.

Second-degree robbery in Rhode Island has a sentence range of five to 30 years in prison, or a fine of up to $10,000, or both. Michael Correia, the Providence police captain, says a typical sentence on the charge includes some years in prison and some years suspended. At press time, Gibbons’s trial had not yet been scheduled.

Last January, Gibbons told the New York Post that he’d robbed the Manhattan bank because he had no money, no food, and nowhere to stay. During his hourlong talk with me at Rikers in May, he didn’t mention his circumstances at all. Instead, he swung from bravado to self-deprecation, offering clever and not-quite-credible explanations. He said he believed many people have thought about robbing a bank. “I’m just more reckless than most people,” he said with a little rueful smile.

Gibbons told me he wanted to write a memoir, but his life wasn’t interesting enough, so he figured he’d add a bank-robbing spree. Most people think if you get caught doing something, you must’ve done it a bunch of times, he lamented, but it’s not true: He only got to two banks. Jail looked good, he suggested, a chance to get writing done.

The Manhattan teller gave Gibbons $1,002 in cash—just enough to make it grand larceny under New York law. The bundle had a hollowed-out rectangle inside that held the dye pack. Gibbons says he wanted to keep it as a souvenir and an art object and take pictures of it, but he figures the cops have it.

For now, Gibbons’s pink-and-silver video camera rests in a New York Police Department evidence room. Gibbons has told a friend he hopes to reclaim it. If he does, the images inside it may yet gain new life, in a work of art that makes sense of Gibbons’s compulsions and dark places. Or the camera may recede into anonymity among the evidence of hundreds of other crimes. It may take years to know which ending unspools.