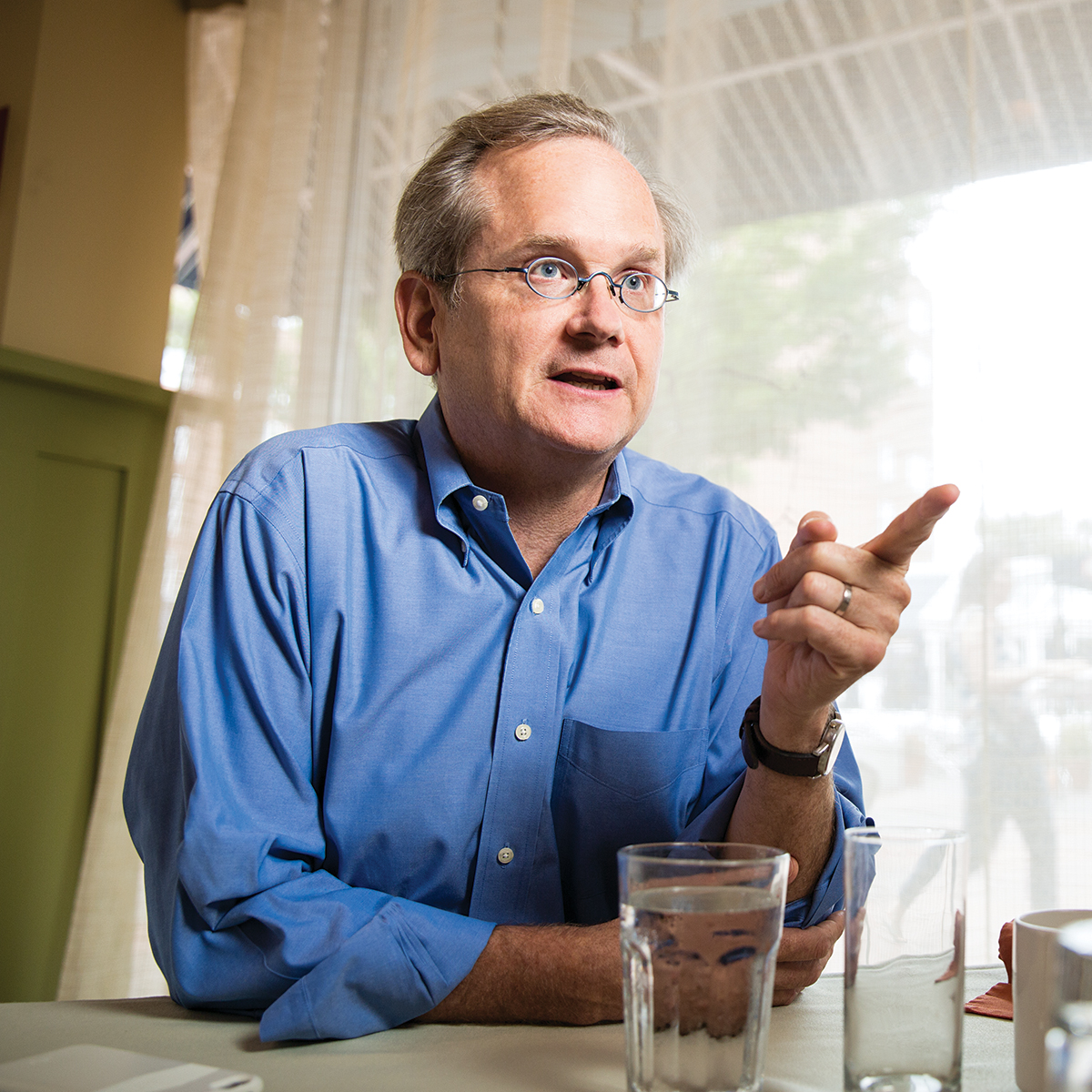

Power Lunch: Larry Lessig

Photograph by Ken Richardson

Larry Lessig thinks American democracy is broken. The Harvard law professor and activist is running for president in the Democratic primary to fight the political influence of ultrawealthy donors. If elected, Lessig says he’ll be a “referendum president,” focused on lobbying Congress to pass a sweeping political reform law. The day after Lessig, 54, announced his campaign in Claremont, New Hampshire, he met Erick Trickey for lunch at Henrietta’s Table, in Harvard Square, where the waiters know Lessig’s order: a vegan chopped salad. Lessig says he’s approaching reform like an entrepreneur, trying for “high risk, high reward.”

Why run for president?

Our poll in 2013 found that 96 percent of Americans believed it was important to reduce the influence of money in politics, and 91 percent thought it was impossible.

Amazingly, there is no relation between what the average voter wants our government to do and what our government does. The largest empirical study in political science finds a nice correlation between actual government decisions and the views of the economic elite and special-interest groups, and no correlation with the views of average voters. In this election so far, 400 families have given half the money.

What reforms are you advocating for?

We’d establish small-dollar public funding—matching grants and vouchers—so congressmen could fund their campaigns without worrying about special interests and lobbying. We would end political gerrymandering. Congress could enact systems for electing representatives that would ensure proportional representation. We’d also attack the incredibly stupid ways we suppress votes in America: voter ID laws, voting on days when it’s hard to vote.

Other candidates, including Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, have talked about public financing systems. So why vote for you?

Other candidates aren’t yet talking about these issues as if they’re day-one issues. If you don’t get this solved on the first day of Congress, you’re not going to get anything else done.

If they come to office in a divided government, arguing for 10 different issues, special interests will say, “No, your mandate is taking on Wall Street or student loans.” In 2007 and 2008, Obama also said we’ve got to deal with lobbying and campaign financing, or we’ll get nothing done. When he got to Washington, he didn’t even propose the change.

So how did the Affordable Care Act get passed?

The Affordable Care Act is a perfect example of the problem. A critical part of that statute says we can’t negotiate the prices of drugs. Obama promised a public [health insurance] option but backed away. Even in his signature legislation, with a supermajority in the Senate, Obama had to bend to satisfy funders.

Why do you think your strategy has a chance?

My focus is bringing people to see that everything they care about sinks or swims on whether we get this reform. If I win, I will have won with a different mandate than a normal, partisan president. We’ll recruit referendum Congressional candidates.

What if Congress rejected your ideas?

One year into the presidency, I’d be on the road 24/7, going to every district where there’s a holdout and campaigning on the idea that we’ve got to get our democracy back.

What would your approach to foreign policy be?

I’ve spent a big chunk of my life outside of the United States. I think I’m the only presidential candidate who has a West Wing episode based around my foreign policy engagement. That’s based on my work on the Georgian constitution.

The United States had moral authority and squandered it after 9/11, with torture, a war that made no sense, and a surveillance state. The idea that you’re going to blow up a bunch of people and then have peace is completely useless. If ISIS does XYZ, I think you’re forced to step in and defend as best as you can, but I would not commit us in a way that replicates these mistakes.

How would you address an economic crisis?

I believe in the evidence-based theory of economics, which is driven by how actual interventions matter. I believe the 2009 economic stimulus was essential and too small. We should’ve had a bigger, more aggressive stimulus, more focused on the people who were hurt most dramatically by that economic crisis, such people with mortgages that suddenly became underwater mortgages.

I do think we have a genuine question about how long we can bear the kind of monetary policy we’ve seen from the Federal Reserve. There are real social consequences to zero interest rates. Wall Street does well, businesses do well, and ordinary consumers can’t save.

I read that your friendship with Aaron Swartz, the late Internet activist, was your motivation to do this.

He said to me, “Why do you think you’re going to make any progress on the issues you’re working on so long as there is this fundamental corruption in the way our government works?” That conversation led me to give up my work on Internet and copyright policy and shift to this question of corruption. When Aaron died, I dealt with it by doubling down on my commitment.

What are your goals between now and the New Hampshire primary?

We need to get into the debates. I’ve got to beat every other person on that stage. Everything will hang on whether I can convince people that there’s another way to look at this issue. If I do, there’s a shot that the field begins to shift and we’ll get the resources to compete aggressively in New Hampshire and Iowa. Then I have to surprise everybody by how well I do in those two states. Each is a low-probability event, but each increases the probability of the next.

Let’s say you don’t win. What’s the next-best scenario?

I’m in it to win. I didn’t get in it for those other things. But consolation prizes are quite valuable. If I can get to a debate and bring it around the recognition of this fundamental issue first, that would radically increase its importance to the American public and increase the chances of solving it. Even if I don’t get into a debate, by pushing this into the center of the field, we’ve at least gotten the other candidates to acknowledge that this issue ought to be addressed.

The day I announced my campaign, Bernie Sanders had money and politics as number 8 on his list [on his website]. By the end of the day it was number two. Hillary Clinton never mentioned it, but is now talking about a really inventive funding reform.