Mike Sherman’s Fifth Quarter

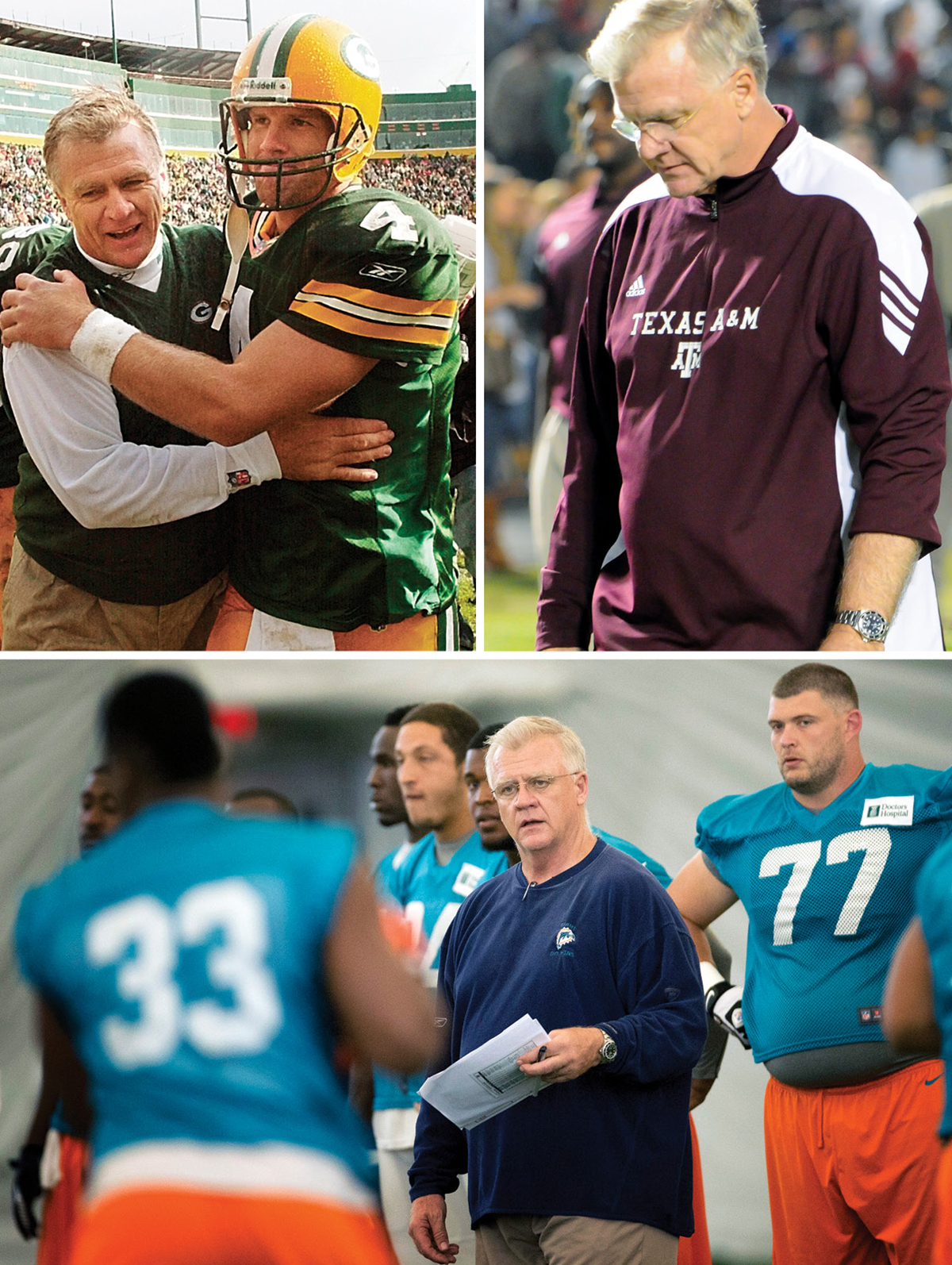

Clockwise from top left: As head coach of the Green Bay Packers, Sherman and quarterback Brett Favre led the team to five consecutive winning seasons from 2000 to 2004; He was fired from his position as head coach of Texas A & M after losing to rival University of Texas in the final Lone Star Showdown, 27–25; Sherman served as offensive coordinator of the Miami Dolphins for just two seasons before losing his job. / Photographs by Morry Gash/AP Images (Green Bay); Cal Sport Media/AP Images (Texas A & M); J Pat Carter/AP Images (Miami)

When Sherman moved to the Cape in 2014 with his wife, Karen, and teenage daughter, Selena, the youngest of their five children, he didn’t plan on coaching high school football. He was just looking forward to settling down after a nearly 35-year grind of a career, enjoying the view of the Bass River from the house he had built in West Dennis, and going fishing on his boat, the Flea Flicker.

But he didn’t want to quit the game altogether—so in early 2015 he started looking into the possibility of starting a summer football camp for high schoolers. He called Nauset’s former football coach and newly hired assistant principal, Keith Kenyon, about possibly using the school’s field. “I see this out-of-state area code on my phone and I pick it up,” Kenyon recalls. “The guy on the other line says, ‘Hi, my name is Mike, and I’d like to talk about some football.’”

The two talked for a while before Kenyon—who’d recently stepped down as coach—threw a Hail Mary: “I told Mike about the opening,” he says. To his surprise—and excitement—Sherman didn’t flat-out say no. The courtship was on. Not that the sell had to be as hard as you might imagine. Sherman’s Massachusetts roots grow deeper than those of the oak trees at the George Wright Golf Course in Hyde Park.

Born in 1954, Michael Francis Sherman was raised along with his four siblings among their extended family in Hyde Park. They lived with their parents on the third floor of his grandfather’s triple-decker on Oak Street. Sherman’s father worked for an insulation company and kept asbestos samples in the trunk of the family car. “The most important person in my life was my father,” he tells me. “He taught me about honesty and integrity.”

Sherman attended Boston Latin for seventh and eighth grade before the family moved to Northborough. There, he enrolled at Algonquin Regional High and became a star athlete on the track, wrestling, and football teams. Baseball pitcher Mark Fidrych—the flaky future rookie of the year with the Detroit Tigers—was in the class behind him, and the two became close friends. In the summers, Sherman would visit his grandparents at their place in Yarmouth on the Cape. He’d work out at the Dennis-Yarmouth High gym during the day and fall asleep at night listening to Ken Coleman calling Red Sox games on the radio. Yaz was his favorite player.

During his senior year, Sherman accepted a football scholarship to Central Connecticut State, where he earned four varsity letters and a degree in English and political science. His first job out of college was as an English teacher and assistant football coach at nearby Stamford High School. From there, he got sucked into the coaching vortex—and became addicted to the pressure, expectations, and, yes, winning. His next stop was Worcester Academy in Massachusetts before he jumped to colleges—Pittsburgh, Tulane, Holy Cross in the Gordie Lockbaum years, Texas A & M as offensive line coach under legend R.C. Slocum, and UCLA, followed by A & M again. He never set out to become an NFL head coach: “I just thought to myself, I want to be the best I can at what I am right now, and if I do that, opportunities will present themselves.”

He was right. In 1997—a comet in the cozy coaching ranks—Sherman accepted Mike Holmgren’s offer to coach tight ends for the Packers. He held the job for two years before following his boss to Seattle as offensive coordinator. In 2000, despite having only three years of NFL experience, Sherman became Green Bay’s head coach, and a year later took on the added title of general manager. The press called him Holmgren’s “detail oriented” and “disciplinarian” protégé. The Packers thrived offensively under Sherman, breaking single-season team records in passing and rushing, and QB Favre maintained his dominance, leading the league in touchdown throws in 2003.

Despite Green Bay’s regular-season success under Sherman, his teams never advanced past the divisional round of the playoffs. The cheese-eating masses, watching Favre’s prime years dwindle, grew impatient. Sherman was fired in 2006 after the team, sabotaged by injuries, went 4–12. It was his only losing year, and Green Bay’s first in 14 seasons.

Next, the coaching carousel spun Sherman to the Houston Texans for two seasons as an assistant coach, before he moved back to College Station, Texas, where he became head coach of a backsliding A & M program. Each year his record improved, from 4–8 in 2008, to 6–7 the next year, to 9–4 and a Cotton Bowl berth the next. But he was fired in 2011 because coaches who get paid $1.8 million a year in the Blazing Hotbed of Football are expected to perform instant miracles—not gradual ones—and to beat archenemy Texas. He had done neither.

Sherman’s parting gift to A & M was the redshirt freshman and future Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Manziel, whom Sherman helped coax out of a verbal commitment to Oregon. Just before Christmas, a few weeks after his dismissal, Sherman wrote a remarkably earnest, 4,300-word Jerry Maguire manifesto to the high school coaches of Texas, thanking them for opening their doors to him on recruiting visits, and offering his advice. In it he preached for them to “be honest but positive,” “embrace your players,” “break down barriers.”

He closed with a flourish: “This ‘game’ also has the ability to bring out the very best in us at times as well as the very worst in us at times. Here is hoping that it brings out the very best in each and every one of us all the time.”

Sherman returned to the NFL as offensive coordinator for the Miami Dolphins in 2012, but was let go after two seasons. At that point, his wife, Karen, decided she was finished moving around. It was time to settle down, to go back to his home of Massachusetts. The couple decided on West Dennis, where Sherman had spent so many summers as a kid, and where they had often brought their children on vacation.

That’s how Sherman wound up on the Cape being recruited for the Nauset coaching job. Yet it was Karen who convinced him to accept. “She told me, ‘How do you know that you were meant to coach the Green Bay Packers? Maybe you were meant to be the coach here. Even if you’re making a difference in just one or two kids’ lives, you’re making a difference,’” Sherman confided.

Every man has an ego, though, and after the heights he had reached in his profession, taking the job at the most out-of-the-way high school in Massachusetts—where the closetlike coach’s office comes furnished with wobbly cafeteria chairs, and the locker room ought to be hashtagged #1980—would be a blow, no matter how noble the intent. Or, as Jacob Hirschberger, Nauset’s tight end and linebacker, put it, “To go down from where he once was and coach a bunch of high school kids who don’t know what the heck they’re doing, it’s tough.” Then he added, “But it means something.”

When Nauset’s preseason football workouts began, the school’s star baseball player, Mike Doherty, didn’t much know or care. That is, until the last Saturday morning in August, when he received a mysterious text from Nauset’s assistant principal, Keith Kenyon, asking him to show up at the school in a couple of hours for an important sports meeting. When Doherty arrived, he found himself joined by a pair of baseball teammates and two of the school’s top basketball players.

Kenyon, flanked by the athletic director and the baseball and basketball coaches, told them they were being recruited to join the football team. He said: We need you. We need leaders. Do it for your school. Do it for a chance to be coached by one of the best.

At the end, Sherman dramatically walked into the room to make the closing pitch. They were asked to make a decision within a week. The boys went home and group-texted to discuss. One basketball player wasn’t interested. One baseball player didn’t want to injure himself. Senior third baseman Sam Majewski was the first to say yes. Doherty and the remaining basketball player then joined as well.

The first practice was a tsunami for the 6-foot, 220-pound Doherty. Unsure how to put on his equipment, he watched the other players get ready in the locker room. The coaches positioned him at guard, but they might as well have dropped him in a space suit on Mars. “We were protecting screens in practice, and I went up to Coach Sherman and said, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing,’” Doherty told me. “He paused, then he gave me a look like, ‘This kid’s never blocked for a screen? You’ve got to be kidding me!’”

Within a week, the basketball player had quit, leaving just Doherty and the tall, fleet-footed Majewski, who was playing linebacker. Either one could have walked away without shame, but they didn’t, subjecting themselves to the losses, Sherman’s grueling demands, and the abject terror of playing for such a towering figure. “I thought this would be a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” Majewski said to me, regarding his decision to stay on the team.

It certainly would.

It’s less than a week removed from the September blowout loss to Cardinal Spellman when Sherman drives his hardtop Jeep Cherokee to the grass practice field, which is set more than a quarter-mile from the school. The sun is already hidden behind the pines, and the players are grimy, exhausted, and ready to head home for dinner and homework. But before they escape to the locker room, the coach calls them over to his vehicle.

The season has started poorly for the Warriors. They played their first game at home against the top-ranked team in western Massachusetts, East Longmeadow, whose senior running back, Mike Maggipinto, came into the year aiming to break the state’s career rushing record. The Nauset stands were crammed with fans eager to find out if the school’s lovable football misfits had been somehow miraculously transformed under Sherman, like in a Disney movie. They got their answer immediately, when East Longmeadow returned the opening kickoff 80 yards for a touchdown. The Warriors lost 42–7. Then came Cardinal Spellman, which ended with a similar result.

As the boys reach the coach behind his vehicle, they see a metal wastebasket on the ground next to his feet. The smell of gasoline wafts around them.

“Don’t hold onto the losses,” he tells them, grabbing a pile of notebooks and tossing them into the trash can. “You have to live in the present.”

Sherman then takes file folders, Bible-thick with scouting reports and game plans, and throws them in. Then some game tapes. He balls up the shirt he wore before the Cardinal Spellman game. Thunk—into the can.

Sherman lights a match and throws it in. A flame shoots into the air, almost high enough to singe his white eyebrows.

“We got the message,” Van Vleck tells me later. “He wanted us to move on.”

The next day, in the homecoming game against Sandwich, the ploy looks ingenious—at first. The Warriors take a 6–0 lead early in the first quarter on a Van Vleck quick pitch to running back Atkinson, who sprints 7 yards into the end zone. The crowd of 400 or so fans on the Nauset bleachers jump to their feet. A cowbell rings. It’s the team’s first lead of the season! The cheerleaders look at one another for a second, then dust the cobwebs off their post-touchdown cheer.

“Get! Those! Extra points!”

The kick is good. Five plays later, though, Sandwich answers with a touchdown. Then another. Then another. And then another. By early in the third, the enemy is up 27–7. Nauset gamely counters in the fourth with a desperate comeback, as Van Vleck and McGough connect on scoring passes of 51 and 54 yards, but the deficit is just too great, and time too short. Final tally: 27–20. The Nauset players trudge off the field, heads bowed.

That’s when Sherman, left to dissect another loss, comes to a realization: It’s not the kids who need to move on from the past—it’s him. He has been too fixated on winning. He has to remind himself that he’s not at A & M or Green Bay anymore.

Instead, he’s on Cape Cod, with a team of kids so green that some didn’t know what a screen pass or flea flicker was when the season started. A team so bereft of talent that he’d snagged upperclassmen from the baseball and basketball teams who had never played the game. A team so scant in numbers that they don’t have enough kids to field a JV squad. Sherman realizes that if he doesn’t make the practices more fun and the experience more educational for the kids, he’s failing them and himself.

So he decides to follow his own advice and pour gasoline on his old priorities as a bigtime coach, and throw a match on them. From now on, each week of practice will carry with it a theme—like overcoming adversity, perseverance, or attention to detail. “I was going to accomplish something, no matter what,” he tells me.

What won’t change is Sherman’s commitment. He’ll keep preparing each week as if Nauset is in the running for the state championship—or as if he’s coaching in the Cotton Bowl or NFC Championship Game. He’ll still obsessively spend hour upon waking hour scripting practices, breaking down films of opponents, even studying NFL games to learn new tricks on offense and defense, and of course plotting his next life lesson for the players. It’s the only way he knows how to work. He hopes this quiet example and unwavering dedication will be his greatest lesson.