The Boss: Sean O’Brien and the Teamsters Attempt an Extreme Makeover

Portrait by Jason Grow

Every spring, Teamsters Local 25, Boston’s most notorious union, hosts a gala downtown. It’s likely the only mainstay on the city’s social calendar where working stiffs with mustaches, bellies, and leather Teamsters vests share a dance floor with suits from the State House.

The event benefits Autism Speaks, a charity to which Local 25 has contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars. Nearly a thousand guests show up, including, in recent years, Senator Elizabeth Warren, Congressman Joe Kennedy III, and Mayor Marty Walsh, as well as film director David O. Russell and actor Chris Cooper. Ben Affleck lends his name to the event as a committee member. And standing at the center of it all like a beloved prom king is Local 25 president Sean O’Brien.

Stout, barrel chested, and with a shaved head, O’Brien has a look that says, You don’t want a piece of me. A former linebacker, he never sets foot on the dance floor but sustains a steady jig posing for photos with old friends and personally shaking hands with each newcomer. “If he ever stops for too long,” a partygoer says, “a line of people forms who want to talk to him. He’s the life of the party.”

In total, O’Brien has raised more than $5 million for charitable causes. “He’s not just cutting checks,” says Larry Cancro, who sits on the board of Autism Speaks New England alongside O’Brien. “He’s one of our most active members.” Over the years, he has managed to turn philanthropy into an altruistic and pragmatic calling. O’Brien, of course, is no dummy. After all, high-visibility largesse is good for his true concern: rehabilitating the Teamsters’ image.

For most of its history, Local 25 was not the type of organization to host parties at posh hotels. Members were more likely to turn up in federal court: The union had ties to Whitey Bulger’s Winter Hill Gang; one of its former presidents spent time behind bars; its rank-and-file members have been convicted of crimes ranging from armed truck robbery to embezzlement; its officers once had a reputation for shaking down movie crews. In 2011, a retired union member was found dying on a train platform carrying $180,000 in mysterious cash.

O’Brien swears he’s trying to clean up this longtime mess. Local 25’s side business used to be crime; now it’s philanthropy. Once a nearly exclusive club for men of Italian and Irish descent, it now counts hundreds of East African immigrants among its ranks. In the past, threatening strikes and pounding fists on tables won concessions from employers; now the union reaches deals through what O’Brien calls his negotiating “finesse.” O’Brien’s friends in high places—including Massachusetts House Speaker Robert DeLeo, state Attorney General Maura Healey, and Warren—have looked on with admiration. Former Governor Deval Patrick even appointed him to the board of directors of Massport, which employs hundreds of Local 25 members.

Meanwhile, O’Brien, 44, has climbed the ranks of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT), one of the most powerful labor unions in the world. In addition to leading Local 25, he is the head of the IBT’s governing council in New England and a vice president of the international body (a position he is defending in this month’s international Teamsters election). He is also a close ally of Jimmy Hoffa Jr., the IBT’s president—a job O’Brien could one day fill.

But cracks in the union’s—and O’Brien’s—new image are starting to show. Last year, five Teamsters from Local 25, including O’Brien’s second in command, were indicted on federal extortion charges. O’Brien himself has been suspended from union duties for threatening voters in a Teamsters election. His admirers describe these incidents as aberrations and defend their friend as a champion of the working class—and of Charlestown, Local 25’s historical home. O’Brien’s critics, meanwhile, call him a strongman who perpetuates the union’s long-standing culture of thuggery.

From a distance, trouble with the feds and accusations of heavy-handedness might sound pro forma in the world of Local 25. This time, though, O’Brien’s troubles extend far deeper, rooted in ex–labor leader Walsh’s mayoral administration and a controversial extortion investigation that has ensnared City Hall officials. Carmen Ortiz, Massachusetts’ tenacious United States attorney, has indicted two members of Walsh’s staff, Ken Brissette and Tim Sullivan, for allegedly withholding permits from organizers of the Boston Calling music festival until they hired unionized workers. Then there’s the whole Top Chef incident.

Two years ago, Local 25 discovered that a TV crew for the cooking-competition show was filming in the Boston area with nonunion workers. A dozen or so Teamsters confronted the show’s crew at a restaurant in Milton, forming a picket line and allegedly shouting slurs such as nigger, fag, and slut. According to an indictment, some of the members tried to force their way into the restaurant, and car tires were slashed.

Then the real trouble hit. A federal indictment came down alleging that a City Hall official, later identified as Brissette, had warned two Boston restaurants where Top Chef was planning to film that they’d have trouble with Local 25 if they allowed a nonunion crew on their premises. Federal prosecutors framed the warning as collusion with Local 25 and indicted the five Local 25 Teamsters.

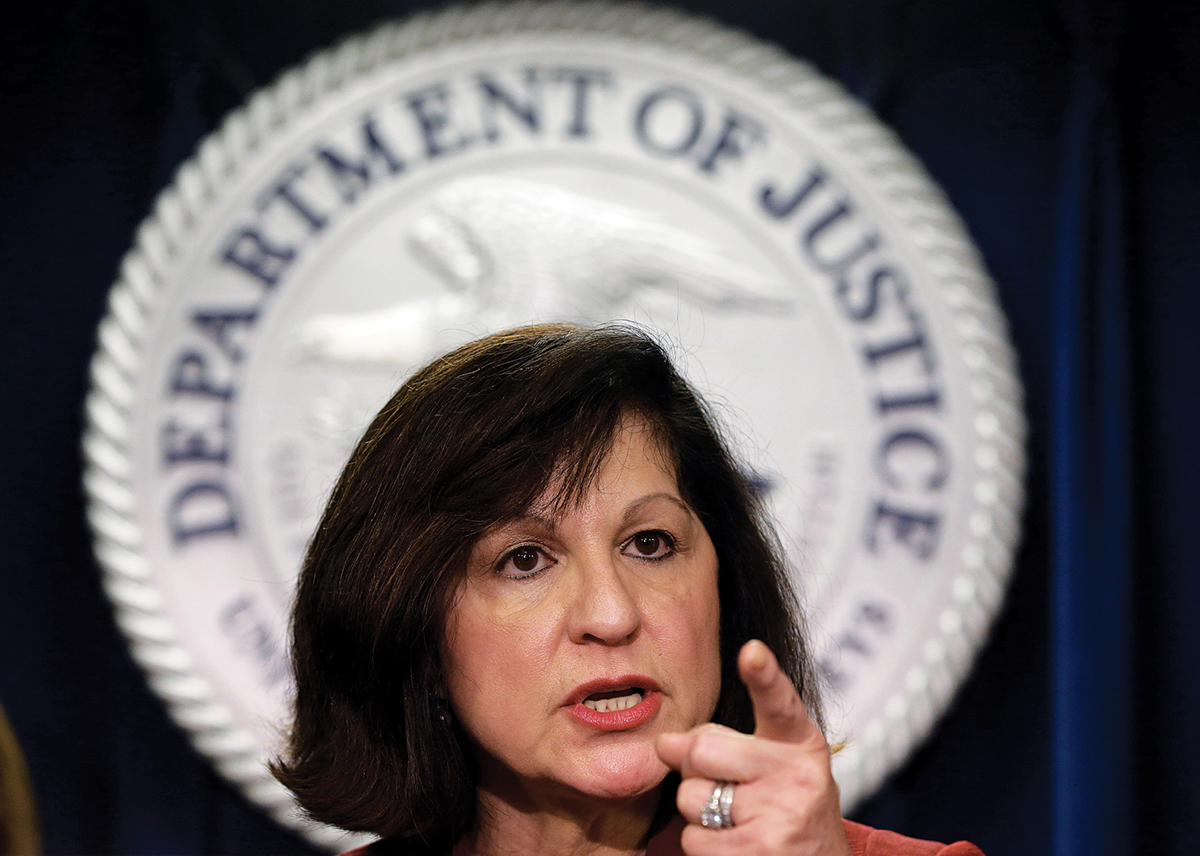

Massachusetts U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz has been criticized by former Attorney General Martha Coakley for prosecuting City Hall officials and members of Local 25. / Photograph by Steven Senne/AP Images

From the start, Ortiz’s critics—a loud and growing club—have cried foul. This isn’t extortion, they say; it’s just a pro-union administration lending a helping hand to working men and women. With the supporters of O’Brien and City Hall pitted against Ortiz and the U.S. Justice Department, however, the probe sheds a light on two very different and colliding Bostons. In one world, the city and O’Brien are tireless champions of the working class and Ortiz is a villain. (Ortiz makes the characterization easy thanks to a history of pursuing low-level offenders.) In the other version, O’Brien leads a gang masquerading as a legitimate outfit, and the city is so in bed with labor that it’s willing to look the other way.

Driving both views is a deeper anxiety about the city’s identity. Is Boston a place where blue-collar power brokers look out for friends and neighbors? Or is it the free-market center of tech and finance that the mayor and governor pitch to outsiders? Our pro-union and pro-business leaders would have us believe there’s room for Boston to be both. If the animosity brought on by O’Brien and Ortiz is anything to go by, though, this town may only be big enough for one Boston or the other.