GE CEO Jeff Immelt Is All In

Portrait by Ken Richardson

On a Friday morning in early March, I went to see Jeff Immelt at General Electric’s temporary office, a converted warehouse in the Seaport complete with exposed-brick walls—a daring motif for the bluest of blue-chip companies. About a week before, a Wall Street Journal article had speculated about who would replace Immelt as CEO, which came as an ominous sign considering Immelt has given no indication that he plans to step down. So I was surprised to find him loose and relaxed. “I hear he’s wearing jeans today,” his press liaison told me when I arrived. “He must be trying to make a statement.”

Upstairs, I spotted Immelt—6-foot-4 and built like an offensive lineman—loping around the office, his tuft of unruly white hair bobbing as he occasionally stopped to chat with employees. At a coffee machine, he rehashed highlights from a recent Celtics-Cavaliers game with a man who seemed about a foot shorter than him. “LeBron dove into the stands,” Immelt said, blinking excitedly. “He almost took out Belichick.”

A few minutes later, Immelt greeted some photographers who had set up a makeshift portrait studio in a corner of the open-plan office. In front of a gray screen, with a spotlight trained on him, he stood with his shoulders slouched, arms hanging. He grinned broadly. There was something self-effacing, even goofy, about his demeanor. It was as if he was trying to make himself smaller, to lessen the impact of his stature, which is staggering both physically and socioeconomically. As the chairman and CEO of one of the world’s biggest companies, he earned $21 million last year while commanding a workforce of 295,000 people. “This is for Boston’s best-looking, right?” Immelt asked, chuckling. A photographer quipped that it was for more of a calendar. “Hold on,” Immelt replied, “I’ll go take my shirt off.”

Cracking jokes with the photographers, Immelt appeared unfazed by the previous week’s Journal article and the criticism that followed. If you believe his friends, that might be because Immelt rarely shows signs of stress—not a bad thing given that Wall Street investors, who own the vast majority of GE, appear to be turning on him. “The heat in the kitchen is way up,” says Nick Heymann, a longtime GE analyst at William Blair.

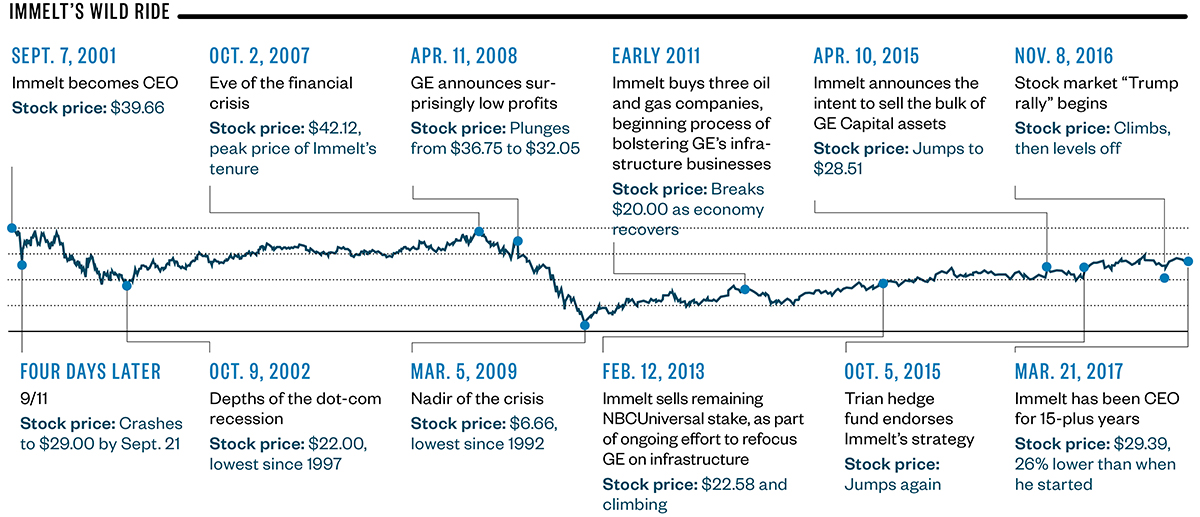

Immelt knows this territory well. Fierce criticism, which escalated recently into agitation for Immelt to step down, has been nearly constant during his 16 years at the helm of GE—a period of decline for one of America’s most venerated companies. Founded by Thomas Edison after he pioneered the incandescent light bulb, GE grew over the next century into a sprawling conglomerate that sold everything from toasters to jet engines and owned an insurance business, not to mention NBC. For decades, it was a darling of Wall Street investors, who viewed the company as a proxy for the American economy—and a reliable source of investment returns. When Immelt took over in 2001 from the legendary Salem native Jack Welch, GE was the most valuable company in the world, worth $402 billion.

Under Immelt, though, GE’s stock price—along with the company’s value—has fallen by about 25 percent, infuriating Wall Street investors, many of whom now want the boss sacked. And the slide hasn’t stopped there. Roughly a dozen publicly traded companies are now worth more than GE—including Facebook, which didn’t even exist when Immelt became CEO. Formerly regarded as America’s premier employer, GE no longer gets its pick of the country’s top young business talent. Today, says Jay Light, dean emeritus of Harvard Business School, “the big company that a lot of people want to go to is Google.”

Click to view larger. / Source: Yahoo Finance

Much of this is not Immelt’s fault. Enormous multinationals such as GE are in decline worldwide. And Immelt has successfully navigated GE through one storm after another, including 9/11, the 2008 financial crisis, and the collapse of oil prices. At the same time, he’s been striving to radically transform the 125-year-old business so it can survive in the 21st century. What was once a massively diversified industrial behemoth will become, in Immelt’s vision, a dedicated infrastructure company that doubles as a top-10 software firm, a bleeding-edge tech innovator, and a leader in a field many see as the next revolution in computing: the Industrial Internet.

If this idea sounds preposterous, that’s because it is. But Immelt, a cerebral, long-term strategist, is certain his vision is the only way forward. As he’s said, “It’s this or bust.” Yet he knows full well that success isn’t guaranteed.

That’s where Boston comes in. For 42 years until last summer, GE’s headquarters was a grassy corporate complex in suburban Fairfield, Connecticut—isolated from the world and, especially, from the centers of technological innovation. Being able to “look out the window and see deer” had become a problem, Immelt has said. Boston, on the other hand, while it lags behind California and possibly even New York in headline-grabbing, consumer-oriented startups, is a leader in the kind of tech that attracts CEOs rather than smartphone-wielding teens. “[Boston’s] strengths are robotics, supply chain management, enterprise software, artificial intelligence, database technology,” says Maia Heymann, a Kendall Square venture capitalist. “This is the tech GE is looking for.”

Governor Charlie Baker and Mayor Marty Walsh might like to think that their negotiating skills and the more than $145 million in financial perks they offered GE are what enticed the company to move its world headquarters here. In reality, though, it was Boston’s brains and tech—ranging from startups to university labs—that sealed the deal. (The perks, Immelt told me, “weren’t the best incentives we saw.”) For Immelt, the move to Boston is meant to be the next phase of his ongoing transformation of GE, not a final act as CEO—as some investors would prefer. Last year, he even dropped $7.5 million on a Commonwealth Avenue townhouse, as if to send the message I’m here to stay. The mayor, the governor, and local CEOs are rooting for him. They’d like to see Immelt last long enough to restore GE to its former glory and, along the way, transform business in Boston. The question is: Can he do it before Wall Street shoves him out the door?

When I sat down with Immelt after his photo shoot to discuss his grand plans, he adopted his typical interview style: folksy charm that masks, with some success, the fact that everything he says is calibrated to spare GE and himself any harm. Many of his answers began with a disarming Oh gosh, and it struck me as we spoke that he might make an excellent politician in the mold of Barack Obama—friendly and professorial but, above all, restrained. When I asked, for instance, how he met his wife (she worked with him at GE in the early ’80s), he demurred, saying, “Well, I can’t tell you everything.” Can you tell me anything? I asked. He chuckled, and then said, flatly, “No.”