What’s Behind Mitt Romney’s Run for Senator in Utah?

Massachusetts’ favorite son is bucking to represent Utah in the U.S. Senate. But what's he really running for?

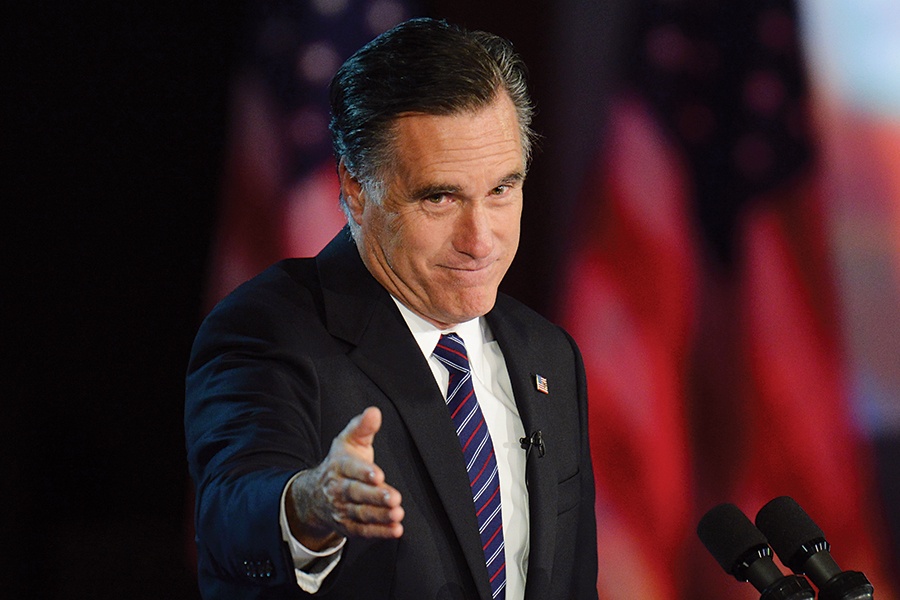

Photo from Getty Images

On a warm Saturday this spring, the cavernous Maverik Center in West Valley City, Utah, buzzes with the kind of carnival atmosphere that has become a staple of American political life. Down on the floor of the glittering arena, which also serves as the home of the Utah Grizzlies hockey team, candidates for major office hawk their visions for the future from inside trade-show-style booths as delegates wander aimlessly. In one stall, a cherub-faced Senate candidate named Sam Parker has hoisted himself onto a box and bellows that America has taken the devil’s path ever since the 17th Amendment mandated citizen election of U.S. senators. Nearby, Senate candidate Brian Jenkins campaigns in character as Abraham Lincoln, beard and all. Everywhere I look, would-be politicos are putting their spin on the same story: It’s time to give the establishment the boot. Welcome to Utah’s GOP Nominating Convention.

Amid these conservative fire-breathers, one smooth, polished, and unflappably cheerful figure stands out: Mitt Romney, former governor of Massachusetts, who’s once again gunning for office. Handsome as ever, with his trademark plastic grin, he poses for pictures, slaps backs, and answers questions with the aplomb of a well-practiced, carefully calibrated politician. I join a crowd of delegates watching him defend his on-again, off-again relationship with Donald Trump and offer his views on Obamacare. A close observer of Romney since the ’90s, I notice that many of his answers are better and more smoothly delivered than in the past. Still, in many ways he’s the same ol’ Mitt that we’ve known for decades—with one notable exception: a new bald spot, not especially large, just behind the crown of his perfectly sculpted head. He keeps it hidden by combing strands of suspiciously dark hair across it—just like the careful, unbreakable façade Romney has always maintained.

Today, he’s vying for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by the retiring Republican Orrin Hatch. Romney did not grant an interview for this article, but it probably wouldn’t have mattered anyway. His commitment to his own myths—to the selling of himself as a product—is so complete that it’s often hard to know when he’s being sincere. After all, this is the politician who once described his Massachusetts governorship as “severely conservative”—a shock to anyone who lived in the commonwealth during his reign. Indeed, turning down my request was part of a strategy to decline all interviews with out-of-state media, showing Utah voters that his sole focus is on them.

The thing is, while these calculated but clumsy pivots to one constituency or another can make Romney look like a power-hungry cynic—and let’s be honest, they often have—his underlying motives can be simpler, and purer, than outsiders and pundits like me often assume. On one level, Romney and those close to him have long claimed that all he’s ever wanted is to serve, be it for his family, the church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or his country. “He was raised in this household of public service,” says longtime friend Fraser Bullock. “That gets into your DNA.” That may very well be true, and his Senate campaign can be explained that way. But it also points to another deeper and more interesting explanation for why, in his seventies, Romney is still bucking to go to Capitol Hill: to fulfill his destiny and salvage a heritage of family political greatness (and loss) inherited from the same man and woman who passed down that near-perfect head of hair.

Like Mitt, his father, George Romney, was governor of a left-leaning state who believed that he was destined to be president—that the Republican Party needed him to rescue it from ascending hard-liners and bigots, led then by Richard Nixon. But 50 years ago, thanks in part to an embarrassing public gaffe, George failed, then had to watch his nation and party sink into war and unprecedented scandal. Likewise, Mitt’s mother, Lenore, ran for Senate in 1970 and lost painfully. His older brother, Scott, once expected to succeed in politics, was derailed partly by failed marriages. It has been up to Mitt to bear the family’s political burden—and all he has to show for it is a single term as Massachusetts governor, a failed 1994 campaign for U.S. Senate, and two unsuccessful presidential runs.

Now, however, with a seemingly unlosable race for Senate in Utah, Romney has the chance to ensure that his legacy—and the family’s political history—doesn’t end with his sad 2012 election-night concession speech at the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center. The question, though, is whether he’s running for office again because he feels his country needs him, or because he needs his country to expunge the failures of the past and give the Romney name one last shot at greatness.

That the Romneys are meant to make an important mark through public service is taken as a kind of dogma in certain circles. People around Romney believe it, Mormon church leaders believe it, and, most important, family members believe it whole-hog. “The Romney family, and Mitt,” says one of Romney’s top former consultants, “like the idea of the multigenerational line of Romneys holding political office.”

But those who know Romney insist that he has never wanted the world to speak of “the Romneys” like they do the Kennedys or Bushes—dynasties rich in scandal and privilege. Instead, he hopes his family will be remembered for its selflessness. “Clearly, the governor is motivated to serve,” says former Massachusetts Governor Jane Swift, whose praise of Romney has been spare since she had to bow out of the 2002 Republican gubernatorial primary after he joined the race. “In this era, when many folks are discouraged and leaving the party, I give him huge credit for continuing to be a voice of reason.” This admittedly noble conviction is coupled with the equally sincere belief that the nation desperately needs him. “If not Mitt, who?” his wife, Ann, wrote in her 2015 memoir, explaining his decision to run for president in 2008.

This worldview—a heady, often contradictory mélange of humility and hubris—seems to stem in part from the Mormon church’s notion of great families, whose best members are destined to lead. Charting the family tree and researching past relatives is not a mere curiosity; it is a commandment of the church. Romney’s bloodlines trace back to the Pilgrims: He’s a direct descendant of Anne Hutchinson, who was driven from the Puritan colony in 1638. Mitt’s great-great-grandfather Parley Parker Pratt served as one of the Latter-day Saints’ original Quorum of Twelve Apostles and helped found and design Salt Lake City as a home for the church. George Romney’s cousin Marion Romney was one of the three LDS leaders who received the revelation from God, in 1978, that the church should allow black priests. In short, the family has long been destined for something great.

That lineage did not always translate to privilege. George Romney was born in Mexico among Mormons who had fled persecution in the United States during the 19th century, and he had to climb from humble beginnings. A self-assured, even self-righteous man by many accounts, he worked his way up to become CEO of American Motors Corporation and then governor of Michigan, building a reputation for principled politics and a fierce, charismatic commitment to whatever he set his mind to. Projecting an aura of moral righteousness, he famously took credit for walking out on the 1964 Republican National Convention over the presidential nomination of hard-liner Barry Goldwater. When George ran against Richard Nixon in 1968—and the bigotry and cynicism that carried Nixon to the White House—he campaigned on a progressive vision for the GOP that included getting out of Vietnam and supporting racial integration. It was a form of Republicanism that Republicans didn’t want. Even so, he had a respectable shot until an earnest slip of the tongue turned into a campaign-ending gaffe. When George blamed his previous pro-war position on the “brainwashing” U.S. officials in Vietnam had given him, his opponents and the media took it as a troubling literal confession. He couldn’t shake it; his supporters abandoned him. George Romney went from 1968 presidential frontrunner to a flatfooted also-ran forced to drop out before the first primary.

Once his own political career was over, George encouraged his wife to step into the ring. Lenore, who combined movie-star beauty with family money, had sacrificed her own career opportunities to buttress George’s. Still, she emerged as the beloved first lady of Michigan, whose sparkling wit and grace shone during her husband’s campaigns. In 1970, she ran an underdog campaign for Senate in Michigan, as a social moderate and opponent of the war. Like her son Mitt, Lenore shirked from the counterpunching that George seemed to relish. She struggled through a bruising primary, winning by just four percentage points. With a divided Republican party in an increasingly Democratic state, and facing considerable sexism, she lost by a landslide in the general election.

Neither of Mitt’s parents ever won federal elected office, nor did they live to see their son’s later political success. Instead, after suffering the slings and arrows of their own campaigns, George and Lenore were on hand daily throughout their son’s wrenching 1994 U.S. Senate loss to Ted Kennedy. “George was really emotional,” says Ronald Scott, author of Mitt Romney: An Inside Look at the Man and His Politics. “He said, ‘My son’s a good, upstanding person; why are they treating him like this?’” George died in 1995; Lenore passed away three years later, during an awful stretch for Mitt that included Ann’s multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Determined as ever, though, Mitt kept trying to work his way back to Great Man status in DC. In 2012, after winning the GOP presidential nomination that his father could not, he seemed poised to finally make it, until his own notorious “47 percent” gaffe derailed his campaign, repeating family history.

The Romneys and their friends have long insisted that Mitt is not the sort of politician who’s constantly calculating his next move.

The opportunities, they maintain, just keep presenting themselves, and he selflessly accepts. Romney’s unsuccessful 1994 Senate race was a one-time agreement to step up for his party, they say, and challenge Ted Kennedy, whose reputation had cratered following the tawdry 1991 rape trial and acquittal of his nephew William Kennedy Smith. When Romney left Massachusetts to take over the scandal-plagued 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, it was merely a perfect chance to serve. “There was no political motivation at all,” says Bullock, who was Romney’s COO and CFO for the Olympics. Likewise, I’m told, Romney was not thinking of his 2002 gubernatorial run as a launchpad for the presidency. After losing the 2008 Republican presidential primary, says Stuart Stevens, chief strategist of Romney’s 2012 campaign, “I never thought he’d run again. He was in La Jolla, writing [his memoir, No Apology]. He seemed happy.”

After losing to Barack Obama in 2012, Stevens and other campaign advisers say that Romney was done running for office. Within weeks of that election, one adviser said, he had picked out a spacious lot in Utah to build his retirement home. So, once again, his decision to run for the open Utah Senate seat was not a carpet-bagging relocation from New England, as pundits have suggested, but a local retiree waking up one day to find himself being recruited to fill Orrin Hatch’s shoes. Never mind how it looked when his Twitter profile changed from “Massachusetts” to “Holladay, UT” within hours of Hatch’s retirement announcement in January.

In truth, it’s hard to see these opportunities as luck or whimsy. Take the retirement of Hatch, which opened up the Senate opportunity for Romney. Hatch publicly promised to not run again during his 2012 reelection campaign—casting Romney’s near-concurrent decision to build a home in Holladay in a very different light. Then, as Hatch appeared to be waffling on that promise, “big-money backers of Mitt Romney” stepped up with “an off-ramp that could ease Hatch out of the Senate,” according to the Salt Lake Tribune, by putting up money for the Hatch Center at the University of Utah, similar to Boston’s Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the U.S. Senate. One of those backers paving the way was Kem Gardner, the former LDS mission president to Boston who helped recruit Romney for the Olympics gig in 1998. “His friends and allies,” says the former consultant, “do things to help position things so he can’t say no.”

Romney learned from his parents’ mistakes—especially his mother’s—and as a result took only the most calculated of risks, entering races when he was either assured of victory or would have a good excuse for failure. Taking on Ted Kennedy in Massachusetts fell into the latter category. Running for governor in 2002—gaining the nomination over Swift, at least—fell into the former. The behind-the-scenes pressure, applied through party operatives and funders, eventually lead to Swift stepping aside, says Scott, the Mitt Romney author. “It was handed to him—it was exactly what he wanted.” And in 2012, he made sure that other strong potential Republican presidential candidates would stand aside, Scott says. “Now in Utah, he’s done it again.”

In his booth at the Utah Republican convention, Romney fields a question about Donald Trump. He’s glad, he says, to have the president’s endorsement but disagrees on issues such as international trade. After all, Romney says in that inimitable way of his, trade is “darn good for Utah.” Make no mistake: Even though he ultimately failed to win the delegates’ nomination, Romney will easily win the Senate race in this overwhelmingly Republican yet Trump-averse state. And in what may well be the final chapter of his political career, people want him to make a stand. The question, though, is whether taking a stand is part of his grander plan.

What exactly is going on under that once-perfect hair is hard to tell. Many Romney backers want him to lead the GOP resistance to Trump. After all, Romney lambasted Trump during the 2016 campaign—even considering entering the race in a late attempt to stop him. But after he joined the Utah Senate race, Romney dramatically toned down his criticism, happily accepted Trump’s endorsement, and declared himself “more of a hawk on immigration than even the president.” Now, both pro- and anti-Trump sides are left guessing which candidate will show up next. “Is he going to be a courageous senator?” Scott asks. “Will the real Romney please stand up?”

The answer depends on who you ask. Cynics will tell you that all you need to do is watch which way the wind is blowing. “People have a lot of expectations for what Mitt will be when he gets to the U.S. Senate,” says the former consultant. “But who he is will be dictated by the political expedience of whatever situation will present itself.” Optimists, on the other hand, see Romney, at last, free of the political calculations that have muddied his career. He can simply be himself and stand up for what he wants. Whatever that might be. “He’s retired, he’s 71, he could spend time with his family,” says Rob Anderson, the Utah GOP chairman.

Romney echoed that sentiment when speaking to delegates at the recent convention. “This is not about my political career,” he said. “I’ve got no political career. I had a business career. This is about serving.” Like all of us, though, he is made up of many parts, and in Romney’s case they seem to include his parents’ failures and their desire to fulfill the family destiny as great leaders to a nation in need. I wouldn’t be surprised to wake up and learn that the entire Senate seat was nothing more than one final stab at ousting Trump and assuming the White House. Arguably, it may well be the moment he’s been waiting for. With a party in revolt and decorum in tatters, it’s not only a chance to win the race his father couldn’t, but to strike a crushing blow against the forces that tore him down. And that, it’s fair to say, would be some legacy.