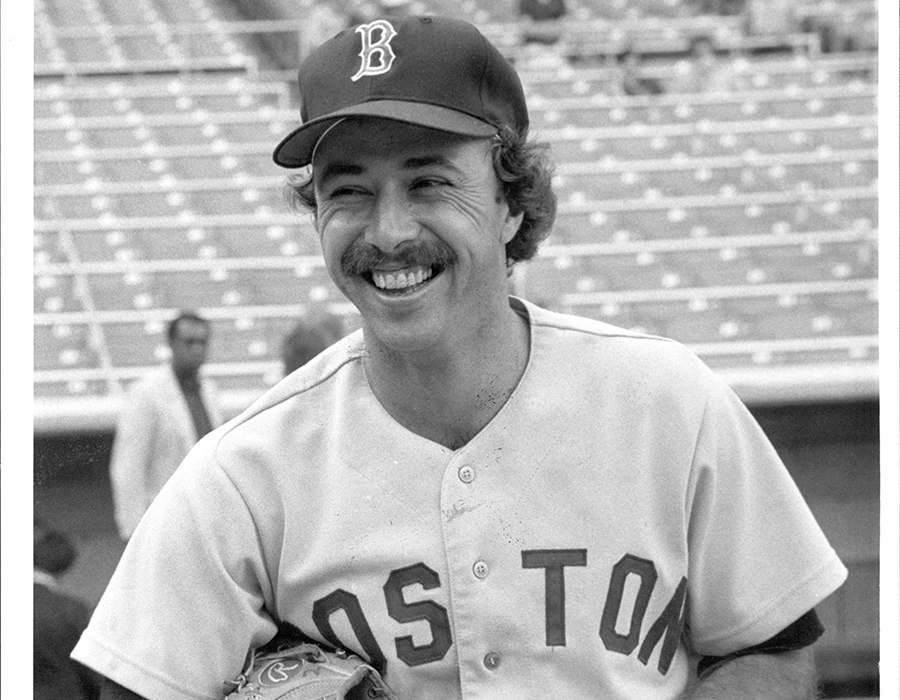

Red Sox Legend Jerry Remy is Ready to Talk About, Well, Everything

For 30-plus years, the Red Sox broadcaster won legions of fans with his on-air antics and guy-at-the-end-of-the-bar charm. Now coming off his latest bout with cancer, our most iconic sports personality isn’t finished yet.

Photo by Ken Richardson

On a bone-chillingly cold evening in mid-January, Jerry Remy—the veteran NESN color man and unofficial president of Red Sox Nation—is sitting shotgun in a double-cab Chevrolet pickup, watching the truck’s quadruple beams cut a tunnel through the gathering gloom. In approximately an hour and a half, Remy is due on stage at the Gracie Theatre, on the campus of Husson University in Bangor, Maine, to sign autographs for fans and participate in a question-and-answer session. But for now, at least, his mind is elsewhere.

“There’ll be food, right?” he asks. “I was told there was a sandwich.”

“There is a sandwich waiting,” confirms Diane Murphy, a manager at Blue Sky Sports & Entertainment, the Norwell-based marketing firm that represents Remy.

“Very good,” Remy says. He seems to visibly relax, and for the next five minutes—the remainder of the drive—he chatters amiably about all manner of subjects: George Steinbrenner (“Bigger than life!”), the emergence of the cell-phone camera and the selfie phenomenon (“Everywhere you go these days, you gotta take a picture!”), and the good fortune of young New England sports fans today (“I’ll tell you, they have no idea, none, not a clue, of what it’s like to lose”). The truck grinds to a halt behind the auditorium. Remy unfolds himself from his seat: first, feet; next, torso; finally, mustache.

“I’ll tell you the truth,” he says, tugging at his tie. “Five years ago? Even three years ago? I would not be standing here today. Never would have gotten me up here. The off-season? That’s when I hung out at home. That’s when I was on the couch, watching TV.”

He means it: Although Remy has been a fan favorite for almost all of his 30-plus-year career as a broadcaster—his in-booth persona is the Funny but Knowledgeable Buddy—until relatively recently, he was, by his own admission, a “real recluse” who found himself “extremely uncomfortable in social situations of any kind.” After road games, he’d retire quickly to his hotel room; after home games, he’d walk down to his car, parked in an optimal position outside of Fenway Park, and beat a hasty retreat back home. “I learned that they made Jersey Street a one-way, and so I’d head out there as soon as I could, zip down Boylston, out onto the Pike—easy,” Remy tells me.

At the age of 66, all of that is starting to change. He has survived four bouts with cancer and is in the midst of an experimental treatment to prevent a fifth occurrence. After a lifetime of crippling social anxiety, he’s finally becoming comfortable in his own skin and feels a sudden desire to give back to his fans. In an effort to let them in, he has embarked on a string of high-profile public appearances, including, most memorably, a turn conducting the Holiday Pops in December. He has made a point of publicly addressing both his battle with lung cancer and his even longer battle with depression and anxiety, which he has dealt with most of his life. And he’s even getting ready to share the story behind his greatest struggle. Five years ago, Remy’s son, Jared, was convicted of murdering girlfriend Jennifer Martel—a tragedy that dragged a long history of Remy family troubles into the light—and Remy alienated legions of fans by battling the Martels for custody of his granddaughter. This summer, however, Remy will publish a lengthy memoir, written with the late Boston Globe reporter Nick Cafardo, that will break a long, uncomfortable silence about his son, who is serving a life sentence in prison for the murder. After a lifetime of retreating into his shell, Remy’s making himself vulnerable like never before.

“It’s been a metamorphosis for him,” Dave O’Brien, NESN’s Red Sox play-by-play announcer and Remy’s partner in the booth, says. “I mean, 10 years ago, would he have gotten up in front of the Boston Pops like that? Would he travel around, talking to fans, doing question-and-answer sessions? Not a chance. But this is Jerry now: He’s been through hell, and he’s going to take his experiences and use them.”

In our conversations, Remy suggested that age was a major driver for his newfound openness. “As I get older,” he says, “I feel like I have more of a story to tell. And I’ve gotten more comfortable than I was in my own skin—more comfortable than I was 15 years ago, much more comfortable than I was 25 years ago.” He pauses and peers down at his hands. “But it’s also the fact that the things I’ve gone through, cancer or depression or anxiety, these are things that a lot of people go through,” he continues. “And they don’t like to talk about it, because it scares them. And honestly, it really scared me, too. I was no different. But look, I’m lucky enough in my position to have a bully pulpit, and I want to use it to help people. Use it to say, ‘Hey, listen, you’re not alone.’”

After a lifetime of seeking solitude, though, it’s a role that could take a little getting used to.

Although Jerry Remy has been a fan favorite for 30-plus years, until relatively recently, he was, by his own admission, “a real recluse.”

The Jerry Remy most Red Sox fans know sits in a small green room overlooking the emerald sprawl of Fenway, surrounded by screens displaying the live feed, and flanked by his play-by-play man. That’s where he comes recognizably alive: the guy-at-the-end-of-the-bar Remy, the affable but deeply knowledgeable Remy, the Remy with the undomesticated Massachusetts accent (see: “Xandah Bogahtz” or the “Amicer Pitch Zone”), unruly hair, and lopsided smile—the Remy “with an amazing authenticity and the ability to connect so well with everyone, to draw this universal love and affection,” as Red Sox president and CEO Sam Kennedy recently put it to me. “He is one of us,” the veteran NESN commentator Tom Caron has said of Remy. “He thinks like us, acts like us, and talks like us. He resonates with his viewers because he looks at the world the same way we do.” Put another way: “Jerry bleeds for New England sports,” O’Brien says. “It’s his heart and his soul. He lives for it.”

In the booth, Remy’s style is warm and wildly discursive—a grab bag of old stories, baseball scholarship, and off-hand observations, some funny, some disarmingly plangent, each one relayed in a relentlessly intimate tone. In my own time as a Sox fan, I have watched Remy bravely bite into a fricasseed grasshopper, perform air guitar, and lapse into hysterics as a fan struggled to put on a plastic poncho; I have also heard him wax poetic at the sight of a big yellow moon looming over the Green Monster. The antics do more than enliven games that might otherwise be dragging sluggishly into the later innings. They make you feel like you’re in the presence of a friend. “I think Jerry’s very genuine,” O’Brien’s predecessor, Don Orsillo, says. “People feel like they know him and that he is part of their family, even if they have never met.”

Outside of the booth, though, Remy was the opposite: awkward, reclusive, and painfully shy. He was raised in working-class Somerset, near Fall River, the first child and only son of a furniture salesman and a dance instructor. He remembers his parents as relentlessly upbeat people; his sister, he tells me, “was the complete opposite of me—happy-go-lucky, friendly.” The baseball diamond was one of the few places he felt truly comfortable. He didn’t have to talk, or not much, anyway; he could just play.

At a young age, Remy’s own potential was not immediately obvious to him. “I felt like the guys I was playing against, at the park, I was better than them,” he says. “But I had no idea that I could get a real career out of it.” Still, Remy was “fast as a horse,” as he put it, and by high school, pro scouts were taking notice.

Remy spent the bulk of his pro career with the Red Sox—seven seasons with the Olde Towne Team—but it was the Angels organization that drafted him after a brief stint in college. He recalls his days in the minor leagues passing in a booze-soaked blur. “People dipped, chewed tobacco, smoked. Did everything,” Remy says. “After the game it was basically, go find a bar somewhere, and drink and smoke until you couldn’t do either anymore, then go back to your room. And then get up and do it again the next day.” When Remy entered the major leagues with the Angels in 1975, he expected a more temperate environment. “But I walked into the clubhouse the first day into my camp, and everybody’s smoking,” he recalls. “The coaches are smoking. The players are smoking. It was great: You could just fire it up. It became part of my life.”

The smoking helped the shy twenty-something feel looser; the bright glare of the limelight filled him with pride. While Remy’s career as a player was a decent one—605 runs scored, 208 stolen bases, a stalwart .275 batting average—he shared the stage with some of the greatest athletes of his generation, from Carl Yastrzemski to Jim Rice. In 1978, he was an integral part of the legendary Red Sox team that won 99 games and advanced to a one-game playoff, only to lose—in devastating fashion—to the New York Yankees. Over time, Remy says, he came to appreciate the hothouse pressures of playing in his hometown market. “You can be a free agent, go to somewhere where nobody gives two shits about you, don’t care if you win or lose. Or you can be here, in Boston, where people live or die over what you do,” he says. “And you take the good with the bad. I would take the good with the bad any day, because people care.” For years, Sox fans loved the local kid done good.

In 1984, hobbled by a persistent knee injury, Remy finally hung up his cleats at the end of his 10th season. After initially entertaining the idea of becoming a coach, he agreed to take a trial run as a broadcaster for NESN, alongside the play-by-play announcer Ned Martin. “I was uncomfortable, terrible, not good at all,” Remy recalls. “I went to my wife and said, ‘I don’t like this. I don’t think I’m doing the right thing here.’ She told me to give it another year. I wasn’t sure, and I’m not sure the Red Sox were real pleased with what I was doing either. But they were willing to give me one more shot. I took it, and things did start to click,” he goes on. “I learned how to set up a play, how to better understand the stuff coming from the truck. I tell you, it was a process.”

As Remy’s life went through all of these changes, he became increasingly aware of a long-standing behavioral pattern beneath the surface. He would sink into inexplicably dark moods—half anger, half sadness—and suddenly lash out. “I’d have these days when I’d wake up pissed for no reason at all, and it’d last four days,” he says. “I’d take it out on everybody. My family, my wife. Four days later, it’d be gone, and then it’d come back the next month.” As time went on, the mood swings took on frightening new shapes. During the late 1980s, before a road-game broadcast in Cleveland, he suddenly felt his heart thudding angrily in his chest. He couldn’t breathe: “They put me on the table. I was lying there. Team doctor came over from the Indians, and said, ‘It looks like you’re having a panic attack.’ I said, ‘Panic attack! Please. What in the hell is a panic attack? I’ve never had one in my life.’”

The attacks continued, and soon triggered a deep depression. “I remember being at my house, and looking out the back window, looking at the woods, and I said, ‘I can’t take any more of this,’” Remy says. “I was afraid to go to bed, because I didn’t want to wake up the next morning. I felt like shit. I was afraid to get up in the morning because I didn’t want to face another day like I had the day before.” He tried therapy, but it didn’t help. “I finally said to the doctor, to the psychiatrist, ‘Hey, fuck this talking,’” Remy says. “It’s not doing me any good. I really need medication.’” He went on a twin regimen of Xanax and a powerful antidepressant. “And finally,” he remembers, “I started to feel better.”

Outwardly, Remy’s career took off. His salary swelled along with his popularity, and the Sox clinched the title that had eluded the organization for so long. In 2004, he hollered louder than anyone when his beloved team finally brought home a championship after 86 years of frustration; that same fall, he rode the duck boats through Boston in the victory parade alongside players and management. “You started to enter an era where we’re at now, where kids grew up expecting the Red Sox to win the World Series, or get to the playoffs, every year,” he says. “It was thrilling.” Privately, though, Remy was about to suffer an enormous setback.

A young Remy during his days playing for the Sox. / Getty Images

In the winter of 2008, Remy came down with the flu—something bronchial, something deep in his chest. His lungs ached and he was sore all over. He tried bed rest and self-medicating with over-the-counter painkillers, but the illness proved stubbornly resistant. After a few days, he got in his car and drove from his home in Wayland to Massachusetts General Hospital to see his physician, Laurence Ronan.

Ronan, knowing Remy’s history with tobacco and nicotine, ordered a chest X-ray; it showed a small dark spot at the bottom of one of the lungs. A CAT scan and biopsy followed. The results were conclusive: Remy, then 57, had Stage 1 lung cancer. If he hoped to survive into his sixties, he needed immediate surgery to remove the tumor. Remy remembers being “scared—just terrified, to the pit of my stomach.”

After the operation, Remy managed to work spring training and a few early-season games before throwing in the towel. “I was weak, fatigued,” he says. “It was obvious to me, and to the people at NESN.” In early May, before a game between the Sox and the Indians, the network had Orsillo read a statement on Remy’s behalf: “I want to focus on completing my recovery so that I can return to work without distractions or disruptions.”

Now, kept away from his team for the first time in decades, a familiar gloom started to envelop him, gray and heavy. In an attempt to shake it one evening, he clicked over to a NESN telecast of the Sox game. “But it hurt to sit there and see an event I knew I was supposed to be working,” Remy says. “I separate my problems with depression into two periods—that moment, that’s when the second period really started for me.” He picked up the remote and changed the channel. It would be months before he watched a Sox game again. “I knew I needed help,” he says.

In 2009, Remy hauled himself off the couch and trucked over to Mass General to see the head of psychiatry. He left with a prescription for a different antidepressant, Lexapro, in a dose that seemed to beat back the depression in a way the previous drug hadn’t. That August, with his cancer in remission, Remy returned to the Fenway Park broadcast booth for the first time in months, just to visit for an inning. As his face appeared on the big screen in center field, the entire stadium seemed to rise to its feet as one. “The outpouring,” Remy says, “was beyond belief.”

Yet in many ways, what O’Brien calls Remy’s personal “hell” was just beginning. In 2013, not long after the Red Sox clinched their third championship in 10 years, Remy’s eldest son, Jared, was arrested for murdering Jennifer Martel, the mother of one of his two children. The Boston Globe published a lengthy exposé on Jared’s past infractions, headlined “For Jared Remy, Leniency Was the Rule until One Lethal Night.” In some corners of Red Sox Nation, there was discussion of whether his father, Jerry, should be allowed to continue broadcasting. “If Jerry Remy sold used cars, then maybe none of it would matter,” the Globe editorial writer Alan Wirzbicki argued at the time. “But Jerry Remy doesn’t sell used cars. His job is to be a particular TV persona—the gentle, chuckling color commentator on Sox games. Playing that role has made him popular. But now, that’s not an image that he can project without turning New England’s collective stomach.”

The fallout from the murder painted an ugly picture that seemed incompatible with the affable Remy on TV. A friend of Martel’s had accused the Remy family of pressuring Martel to drop a restraining order not long before she was killed—a claim Jerry called “nonsense” at the time. Then the Remys battled for custody of Arianna, Jared and Jennifer’s five-year-old daughter, who was at home when her father stabbed her mother to death. In a column for the Boston Herald, Margery Egan gave a voice to many disappointed fans, questioning that decision and pointing out that all three of Remy’s children had been arrested for violent acts. “It’s time,” she wrote, “to acknowledge something terribly wrong at home.” Remy fired back during an interview on WEEI, saying, “You can call us the worst parents in the world, I can accept that. You can call me an enabler, I can accept that. But when you start talking about how we’re going to treat our granddaughter toward her father and say foolish, stupid things like that, I mean that is absurd. That is something we would never, ever expose her to. There’s been no contact; there will be no contact.”

Ultimately, Remy took a leave of absence from the NESN booth, and with his wife issued a statement expressing “sorrow” for the victim’s relatives. “No words can express the sorrow we feel for the Martel family. We are now focusing our attention on our grandchildren and doing what is best for them,” the Remys wrote. When asked, Remy declined to address the episode with me other than calling it “the worst part of our life. It will always be the worst part of our life. Not a day goes by where we don’t think about it.”

Jerry Remy at home in NESN’s studios. / Photo by Ken Richardson

If Remy had previously hid his personal life behind closed doors, that time was over. Now his private life was—for better or for worse—front and center. And on the topic of cancer, at least, he discovered he wanted to talk about it, wanted to explain his own fight in a way that might help others, and maybe even save lives. For the first time ever, he told me, he felt he had an obligation to use the moment as best he could and turn it into an opportunity. While he’d always brought his personality into the broadcast booth to talk baseball, he started talking about what he was going through. “I understood the impulse to pass on the physicals, to ignore any problems,” he says. “But I also understood that you couldn’t do shit like that, because cancer, if it’s caught early, they can deal with it. If it’s not caught early, you’re dead.” It was the start of a sea change in how he dealt with his fans—instead of continuing his lifelong retreat into his shell, he was starting to open up.

The process, however, began slowly. In 2015, back in the NESN broadcast booth after his son’s trial, Remy weathered his third recurrence of lung cancer, necessitating a course of radiation. His body seemed to tolerate the treatment: He never lost any of his hair, never got nauseous. But he was perpetually fatigued. “You learn to take it as it comes; it gets to be a part of your life,” Remy says. “More than that: It gets to be a way of life.” Eventually, Remy’s presence at games grew sporadic—he missed a handful of games in 2016, and in 2017, his doctors told him he’d need surgery to remove another tumor. “They rip your back right open, spread you open, go in to get the cancer,” he says. “It’s not fun.”

Remy was bed-bound for days. In the meantime, the get-well cards and flowers piled up in cardboard boxes that the Red Sox organization and NESN forwarded to his home. “It was a box every day,” he recalls. “Which makes you feel good at first, but then, at some point, you start to feel bad. These people are spending time writing letters to you, right, and you can’t respond to them. You’re failing. So that’s why,” he goes on, “every time I get back on TV, I make a point of thanking everybody for their concern, and to add how good it makes me feel that people care about me like they do.” He felt overwhelming gratitude, but also debt—how could he ever repay this outpouring of love?

Remy did manage to rejoin the booth for the end of the 2017 season, during which time he let fans in on his private life by speaking frequently of his cancer and depression diagnoses. “I’ve always said that if I can get to one person, to convince him or her to get to the doctor sooner rather than later, it’ll be worth it,” he says. “And hopefully I have. I do hear it from fans. They’ll say, ‘Yes. You helped me with my depression. You helped me get help.’ And that makes me feel good. It makes me feel like I’ve done my job.”

The year 2018 started promisingly for Remy: He worked spring training and the start of a season that was poised, even then, to be a record-breaking one. Then, one afternoon not long after the All-Star break, the NESN team was in Toronto for a game when O’Brien got a call from one of the senior producers—Remy had to fly home. “And I knew immediately what that meant,” O’Brien told me. “[The news of cancer] was like someone dropping an anvil on our heads. It’s actually emotionally difficult to think back on that moment, because you’re not only about to lose a partner, but a friend, too. And a lot of us thought, ‘Well, he probably won’t be back this season.’”

In November, at the start of the off-season, Remy announced a new batch of scans on his lungs had come back negative—he was officially cancer free, “for now and hopefully forever,” as he put it at the time. To help ensure the disease stays at bay, through the winter Remy participated in a Mass General pilot trial of a vaccine and immunotherapy that has been shown to halt the growth of tumors in mice; though he continues the regimen, he began scaling back last month. “The idea,” Remy says, “is that my cancer has historically been the same type of cancer, in the same area, and this could prevent it from returning. And I’m hopeful. Because that’s what you do, right? You hope. You hang onto hope.”

As Remy heals, colleagues have begun to notice a change. “Jerry is still the toughest guy I know, hands down.” O’Brien says. “But he’s softened a bit in some ways, and you can see it. He’s more lighthearted, more open.” Suddenly, he’s becoming the same guy off the air as he was on it.

Remy’s schedule in 2019 will be an attenuated one: He won’t work Opening Day, which is slated for March 28 in Seattle, nor will he work any road games west of the Mississippi. And many of the telecasts he does work will feature three-man booths, with O’Brien handling play-by-play, and Remy and former Sox pitcher Dennis Eckersley splitting color duties—another adjustment that will, Remy hopes, allow him to more effectively marshal his energy between treatments at Mass General. “I’ve been wanting to cut back on road games for a while,” Remy says, “and Eck is willing to step up. Also, I’ve got to take into consideration that I haven’t been very reliable because of the cancer. I’ve missed a lot of games. I need to be fair to NESN.”

In November, Remy signed a new two-year contract with the network, which will carry him through the 2020 season. In the past, he had often opted for longer contracts—three years, five years—but he says he was “not really at the point where I want that kind of thing anymore. Because the truth is, I don’t know if I’ll last five more years.”

In mid-January, I flew up to Bangor to watch Remy give his Husson University talk, followed by a question-and-answer session with fans. Tickets for the “VIP experience”—beer and cocktails, an opportunity to pose for a picture with Remy—were 100 bucks a pop; they sold out weeks in advance.

Backstage in the green room, Remy tucked into the long-awaited tuna wrap. An event staffer stuck her head through the door. “Mr. Remy?” she said with a smile. “The VIPs are all lined up for you.” I trailed Remy down a long hallway and into the antechamber to the auditorium, where the meet-and-greet before the Q & A would take place. At the sight of Remy, a roar went up from the crowd; a hundred smartphone camera flashes seemed to go off at once. Remy blinked into the light, a broad smile already plastered across his face. “It humbles you, it surprises you,” Remy told me later of meeting fans. “Every time—every single time—you’re reminded of how lucky you are.”

The line inched forward, a blue and red and white mass of Red Sox jerseys—Williams! Ellsbury! Victorino!—and Red Sox hats and world championship sweatshirts embroidered with the smiling green mug of Wally, the official Red Sox mascot. One by one, the fans dropped memorabilia onto the table for Remy to sign. Baseballs; posters; copies of Remy’s book; a photograph of a family member currently serving in Afghanistan; an older photograph of Remy in the booth with the broadcaster Ned Martin, who passed away a decade ago; a large pint glass from Remy’s eponymous sports bar, in Logan Airport. “You stole that from my restaurant?” Remy asked.

“I bought it!” the fan replied, grinning sheepishly. “I promise I did!”

Lou and Eleanor Miller, an older couple from down near Portland, had put together a book containing images Eleanor had taken at the 100th-anniversary celebrations for Fenway Park, in 2012. She extended the book in Remy’s direction with shaking hands, her eyes filling with tears. “Get better, Jerry,” she said. “Get better.”

Around 8 p.m., Remy made his way onto the auditorium’s stage for an hourlong Q & A session hosted by a local radio personality. The questions ranged in topic—the state of the Sox infield (Remy was optimistic), the prospects for a repeat championship in 2019 (ditto), Xander Bogaerts (“my favorite player!”), Manny Machado (jeers from the crowd)—but were almost always preceded or footnoted by a burble of emotion: “We miss you!” “We love you!” “We love you!”

As the event wound down, Remy cupped a hand over his brow and searched through the front rows. “Where’s Joyce Farwell?” he asked.

A woman, pale and a little unsteady, raised her hand. Remy called her up onto the stage. “Joyce, I met you in the VIP line,” he said, and explained that Joyce was recovering from cancer. “I just want everyone else to meet you, too.” The pair embraced. “She’s going to be okay,” Remy said over her shoulder, radiating warmth, lost in the moment in front of the crowd. “She’s going to be okay.”

And so was he.