Can Any of Boston’s “Oldest Continuously Operating” Landmarks Keep the Title?

The pandemic put their legacies to the test. But what's in a name anyway?

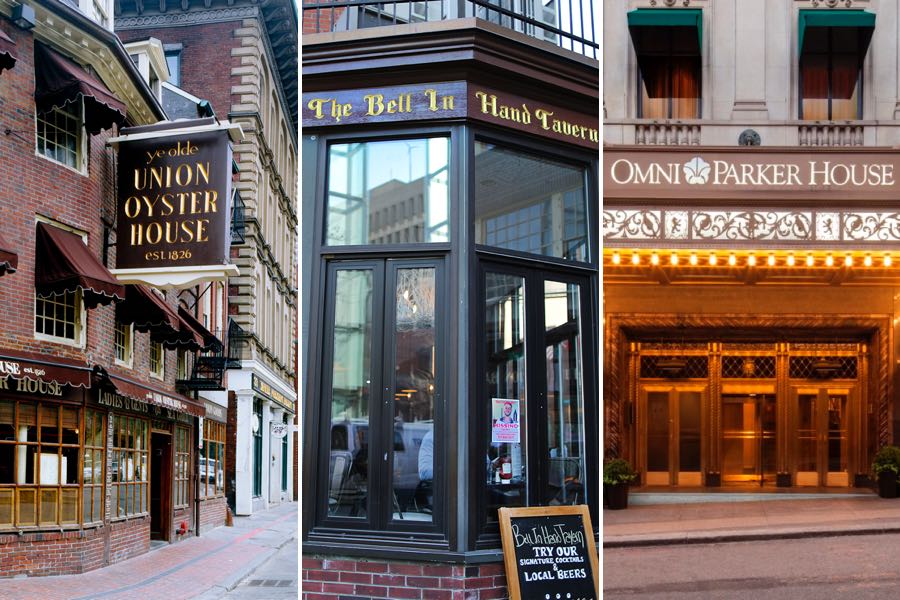

Union Oyster House photo via Getty/Buyenlarge | Bell in Hand Tavern photo via Getty/Boston Globe | Omni Parker House photo provided

Boston prides itself on its rich, still-living history. Ancient cobblestones dating back to the revolution are still embedded in its streets. Transit dorks gush over how the oldest subway tunnel in America is still (on good days) getting Bostonians from A to B. Tourists come here to get up close and personal with the past, and Boston’s authentic and enduring bonds with history will be a draw for them long after the pandemic recedes and the economic recovery begins.

And few aspects of the only-in-Boston historic experience are more tantalizing than that of the “oldest continuously operating” landmark. As locals and visitors have long known, you could, if you were so inclined, grab a Sam Adams at America’s “oldest continuously operating tavern,” sample the chowder at the nation’s “oldest continuously operating restaurant,” then get some shut-eye at the “oldest continuously operating hotel.” Unless your hometown eatery unlocks the secrets of space-time, it’s a pretty strong selling point for the Boston experience.

But many of our favorite landmarks, of course, did not operate continuously this past year. They didn’t have a choice: State and city-mandated lockdowns brought their famously uninterrupted timelines to an abrupt halt. So what are these renowned spots to do with their priceless badges of honor in 2021 and beyond? Do we start the clock at zero?

The answers don’t come easy. In fact, when it comes to what exactly it means to be “consistent” for all this time, they never have.

Joe Milano is not one to gloat about the Union Oyster House’s historical street cred. He doesn’t have to: Back in 2003, researchers with the U.S. Department of Interior combed through centuries of records for cold-hard proof, and ultimately named his restaurant the “oldest continually-operating restaurant and oyster bar in the United States.” The feat is immortalized on a pair of plaques at the restaurant, which for nearly two decades have spoken for themselves. “You can’t negate that,” he says. “Do I bring it up a lot? No. Am I proud of it? Yes, of course.”

Then came last year, when for three months starting just before St. Patrick’s Day, the historic restaurant was closed. But if you ask him, it’s not time to start crowbar-ing those plaques down. After all, he says, the Union Oyster House has closed temporarily many times in its nearly 200 years of serving diners, including after fires in the 1830s and back in 2017.

“I’m not an English major, but I would say ‘continuous’ means it’s uninterrupted,” Milano says. “You can renovate it, or close it for a period of time, maybe a month or two. I don’t think that would negate the continuous aspect at all.”

Milano is not the only one to adopt this attitude about his restaurant’s claim to continuous operation.

“We view it more as we were on pause,” says Debbie Kessler, owner of the Bell in Hand—the nation’s “oldest continuously operating tavern since 1795,” which went dark for nearly a month back in early 2020. “Everything was temporary,” Kessler says. “So if it was like a permanent closure, I would view it as not reopening for years. This is not the case at all. It’s like a blip.”

Party-poopers and sticklers for detail, of course, have always been able to find flaws in her bar’s claim. Over the years the Bell in Hand has operated out of three separate addresses, having moved to its current location in the non-revolutionary era of the 1950s. But, Kessler points out, the bar has retained its name, stayed in the same neighborhood, kept a license as a tavern (not a restaurant, inn, or saloon), and poured drinks for people from all walks of life for more or less the entire time. There was of course another blip in its past, one that was also no fault of its own: It closed for 13 years during Prohibition.

The Omni Parker House Hotel, meanwhile, has a fairly ironclad record of consistency. Since it opened its doors in 1855, according to its general manager John Murtha, the hotel has kept at it incessantly in some capacity every day. There is a big caveat: Much of the building was demolished and rebuilt in 1925. But even then the Parker House was still open to guests: a separate wing with 80 beds stayed open during the construction.

The hotel stopped accepting visitors altogether for the first time ever last year, for a six month period between the start of the pandemic and Labor Day. But Murtha says its hard-earned streak, to his mind, is still valid. It has continued operating, because much of its staff has remained on, handling maintenance as well as such tasks as marketing and booking future stays.

Not everyone in the “oldest continuously operating” community sees eye to eye. For ages, the 173-year-old Franklin County Fair in Greenfield proudly celebrated its heritage as the nation’s “oldest continuously operating county fair in America.” But when fair President Michael Nelson and his board decided it didn’t make financial sense to hold the fair in 2020 given the restrictions, they all agreed their claim to fame had to go. So one day last year, he quietly deleted the phrasing from the fair’s website.

If he’s being honest though, Nelson has always had his doubts. Not far away, the more than 200-year-old Three County Fair in Northampton boasts a similar claim to the record. So where did it come from? “To be honest, I have no clue at all,” Nelson says, laughing. “I just know that somewhere along the line, somebody started calling us that.” The way he sees it, any question on the matter has now been resolved. The Three County Fair went on as planned this year, albeit a scaled-down version, so go ahead and pin the ribbon on them. People who come to the Franklin County Fair with their families year after year for the hometown pride, the fatty fried snacks, and the demolition derby aren’t likely to be fazed.

Still, Nelson was shocked when I told him his peers in Boston didn’t share his sense of strict adherence to the rules, and that they’re all keeping their titles. “Are they? Interesting,” he said. He’s now chewing over a replacement for the site: “One of the oldest running fairs.”

“Which is absolutely what we are,” he says, adding, “I think that’s a pretty great title.”

In the end it probably won’t matter much, for him or those rule-bending Bostonians. History has always been about making sense of complex events and telling easy-to-digest stories about them. What’s important is that these places have value because they’re very, very old—and they’re ours. So what if they have to fudge it a little?