Tsarnaev, the Death Penalty, Three Murders in Waltham, and Me

In anticipation of her forthcoming book, the author argues that when it comes to punishing Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, there is more than meets the eye.

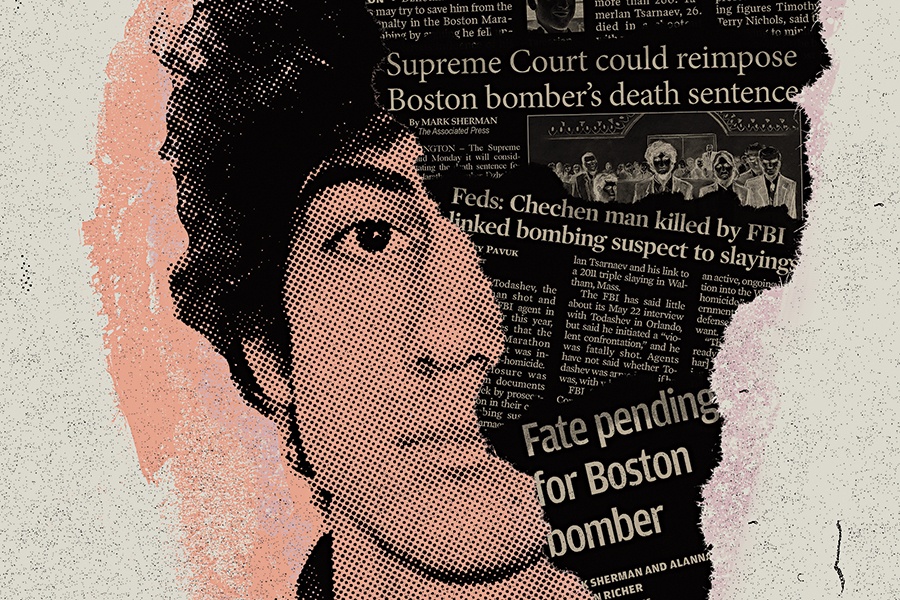

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Photo provided by FBI via Getty Images

One clammy day in October, the nation’s deputy solicitor general, Eric Feigin, stood in front of nine U.S. Supreme Court justices and spoke about a murder in Waltham. More than a decade ago, on September 11, 2011, three men were brutally slayed in a second-floor apartment: throats slit, heads turned to the right, marijuana dumped on two of the bodies, and $5,000 in cash left behind at the scene. “We’ll never know how or why three drug dealers were killed,” Feigin told the highest court in the land.

Feigin’s statement about the obscure killings in a Boston suburb sits at the crux of the federal government’s argument in a totally different case—the one regarding whether to execute convicted Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. After he received a death sentence following his initial trial in 2015, a panel of three federal appeals judges ruled that Dzhokhar had been denied the right to a vigorous defense because the original judge had precluded the presentation of potentially relevant evidence and testimony related to the Waltham murders, in addition to other issues with his first trial. Unless the government opted to hold Dzhokhar’s sentencing phase of the trial all over again, the appeals judges declared, Dzhokhar’s death sentence would be reduced to life in prison. In a highly unusual move, the government chose neither option and appealed straight to the U.S. Supreme Court.

How are the Waltham murders and the marathon murders related? Through Tamerlan Tsarnaev, Dzhokhar’s late brother and co-conspirator in the marathon bombings, who has also been suspected in the Waltham homicides (though the investigation still remains open). Had Dzhokhar’s defense team been able to present evidence related to the Waltham murders at the original trial, Dzhokhar’s lawyers contend, they could have argued that Tamerlan, seven years Dzhokhar’s senior, had become a radicalized Muslim before Dzhokhar, that he’d committed a violent act previously and independently from Dzhokhar, and therefore he could have intimidated his younger brother and must have played a larger role in the marathon bombings. Following this logic, Dzhokhar is still guilty under the law, but arguably less culpable than the government claimed and does not deserve to die.

This so-called “Svengali defense” has worked before: See the DC sniper attacks. In that case, the younger perpetrator was sentenced to life in prison and the elder perpetrator was sentenced to death after the defense team was able to call a witness who watched the elder train the teenager to overcome his fear of shooting human targets. Dzhokhar’s defense attorneys didn’t have many witnesses who could testify about a similar dynamic between the Tsarnaev brothers. What they did have was Tamerlan’s alleged involvement in the Waltham murders—until, that is, they didn’t. That left prosecutors free to argue that Tamerlan was merely a “bossy” older brother and not, as the appellate judges later put it, “a stone-cold killer” who convinced his younger brother to help him.

In Boston, the federal government’s decision to pursue the death penalty for Dzhokhar by petitioning the U.S. Supreme Court rather than accept a life sentence was the subject of widespread debate. Death penalty opponents found it disappointing. And odd. After all, the relatively new Biden administration has vowed not to seek any more federal executions, yet it remains hell-bent on pursuing this last one.

At the same time, here in Massachusetts, there is another—less obvious—cost to the government’s dogged pursuit of the death penalty. It arguably gives federal law enforcement a vested interest in not getting to the bottom of the Waltham murders. It also ensures that no one declares the slayings an act of terrorism, lest that muddy the government’s argument for the death penalty for Dzhokhar. Functionally, it seems, Deputy Solicitor General Feigin’s statement to the Supreme Court—that no one will ever know the Waltham killers’ identities—is not so much a fact as a rather self-serving command: Leave this stone unturned.

As a result, the triple homicide in Waltham has been handled almost exclusively by state and local law enforcement. For a decade, the case has wallowed in the Middlesex County District Attorney’s Office, an agency that, from the get-go, has seemed to show little interest in pursuing it aggressively. Throughout it all, the friends and family of the Waltham victims have been left with the painful legacy of so many unanswered questions about what happened to their loved ones. I count myself among those friends.

I was standing in the NECN newsroom when I first heard that police had discovered three corpses in a second-floor apartment on a dead-end street in Waltham. The names of the victims had not yet been released, but I found myself intensely curious about this unusual crime.

At the time, I was a freelance, overnight production assistant fresh out of college, but I desperately wanted a shot at working as a reporter. I thought this story could be my big break. Several days later, authorities sent out a press release revealing the names of the deceased: Brendan Mess, 25, Raphael Teken, 37, and Erik Weissman, 31.

Erik had been my friend. I’d met him four years earlier, when I was 19, through some childhood friends. We got high together, I occasionally bought weed from him, and we quickly became close. He had a gentle soul, a quick mind, and a kind heart. Together, we would go on long drives and have endless conversations, deep ones. He believed in me, telling me I would be a writer long before I believed it myself.

Erik and the other two victims regularly sold marijuana. They believed that cannabis could heal, and dreamed of a time when it would become legal. But it wasn’t. I told Erik that my father was a criminal defense attorney and that I knew things often ended badly for people in his line of business. When he later got busted on a drug charge, my father assumed his defense.

In the weeks of shock and grief after learning he was dead, I lost my taste for the crime beat and quit. I told my news director I thought there was more to the story, but I wasn’t a reporter and my personal relationship to the victim precluded me from pursuing the case in a traditional newsroom. Plus, I figured, investigators would do everything they could to solve the gruesome murder anyway.

I was wrong. Even though the Middlesex County DA announced that the assailants were most likely known to the decedents—there was no sign of forced entry to the apartment—investigators did not appear eager to interview the victims’ inner circle of friends, which included Tamerlan, those friends tell me. Not even when police investigators later learned about Tamerlan’s conspicuous absence from Mess’s funeral did they try to talk to him, the New York Times reported.

It wasn’t just Tamerlan, though. Investigators seemed largely uninterested in following up on leads, according to dozens of interviews with individuals close to the case including friends, family, neighbors, and members of law enforcement. Shortly after the Waltham murders, law enforcement officials told the Weissman family that they figured someone would tell them what happened on the night of the murder when they needed a plea bargain for another crime. The message received by the Weissman family was that until then investigators would wait.

That break came 19 months later, but not in a way anyone had expected. Two pressure-cooker bombs were placed near the Boston Marathon finish line, and Tamerlan was responsible.

About one month after the marathon bombings, an FBI agent, along with two Massachusetts state troopers, traveled to Florida to interview Ibragim Todashev, an associate of Tamerlan who trained at the same gym as Tamerlan and Mess. During questioning, Todashev reportedly confessed on tape to going with Tamerlan to the Waltham apartment, where they robbed the victims of their “drug monies.” Todashev said he was unaware of Tamerlan’s plan to kill anyone, which he explained Tamerlan said was necessary to eliminate witnesses. The feds never got any more information out of Todashev. During the interview, he was shot and killed by the FBI agent in an act that was later ruled self-defense.

Despite Todashev’s confession, law enforcement has yet to officially pin the Waltham murders on him or Tamerlan. Instead, government attorneys have discredited Todashev’s statement, calling him “unhinged” and saying his confession is unreliable due to discrepancies between what he said and what officers found at the crime scene. These actions have served to bolster their argument for capital punishment and keep the Waltham murders out of the Boston Marathon bombings trial.

Not long after Todashev was killed, the Middlesex County District Attorney’s Office reassumed sole jurisdiction of the Waltham murders, and according to the government’s attorneys, barred federal investigators from accessing state evidence. A statement from the FBI confirmed that the bureau classifies the Waltham murders “as a state murder case under the jurisdiction of the Middlesex County District Attorney’s Office.” Since then, the office has failed to publicly release any more information about the case. After Todashev was killed, I quit my job, flew to Florida, and began investigating the case as a freelance journalist. I haven’t stopped since.

Key to the FBI’s ability to stay out of the Waltham investigations is the agency’s contention that the murders were not an act of terrorism, something that would put the case squarely in its jurisdiction. Government attorneys later took this same position leading up to the original marathon bombings trial, furthering their bid for the death penalty. Arguing that the Waltham killings were not terrorism-related fit their narrative that the brothers had been radicalized around the same time on their own accords and shared equal blame for the marathon bombings.

There are many reasons, however, to think that the Waltham murders were, in fact, a terrorist act, which the FBI defines as a “violent or criminal act committed…to further ideological goals.” One thing we know about Tamerlan is that before he became a terrorist, he was an anti-Semite. People who were close to Tamerlan say that in the late aughts he grew increasingly vocal about his anti-Semitic beliefs. According to a Reuters story, in 2011 Russian intelligence recorded a conversation between Tamerlan and his mother during which they discussed Israel, Palestine, and the possibility of Tamerlan traveling there to wage jihad. Waltham victims Weissman and Teken were not only Jewish, but Israeli.

If Tamerlan was behind the criminal acts in Waltham, the killings were likely driven, at least in part, by his anti-Semitic views. Tamerlan had been close friends with Mess and had disputes with him and Teken about Israel.

It’s also tough to brush aside the date of the murders, the 10th anniversary of 9/11. Was it an echo, or an homage even, to the most monumental terrorist event in our nation’s history? And what about Tamerlan’s six-month trip to Dagestan, which he undertook four months after the Waltham killings with the goal of meeting with terrorist leaders?

In addition to barring evidence about Tamerlan’s potential involvement in the Waltham murders during the original marathon bombings trial, the court also prohibited Dzhokhar’s defense team from introducing Tamerlan’s radical-leaning reading list: several conspiracy theory publications, such as Sovereign magazine, which, in the lead-up to the murders and the bombings, published stories suggesting Israel was responsible for 9/11 and that domestic terrorism was the “required response to tyranny.” Hearing transcripts show that in the weeks surrounding the murder, Tamerlan was reading texts in which Al Qaeda organizer Anwar al-Awlaki justified stealing from infidels to fund jihad. There were also messages in which Tamerlan and Todashev conferred with each other about religiously motivated violence and why that may or may not be justified. This evidence was blocked. Dzhokhar’s comment, allegedly relayed to a friend in the months leading up to the bombings, that his elder brother had carried out “jihad in Waltham,” was also not allowed to be heard in court.

Despite this evidence, Feigin argued that the Waltham murders were “very differently motivated” from the marathon bombings and were undertaken “in order to cover up who had committed the robbery of three drug dealers.” To help support this argument, government lawyers have cited part of Todashev’s confession—the same confession they have called unreliable—in which Todashev said the murders were not planned, but rather Tamerlan’s last-minute idea to ensure they could not be identified. That is hard to buy. Are we to believe that Tamerlan only realized after binding, torturing, and robbing a close friend that he would most certainly be recognized, and then decided in that instant to kill the robbery victims?

The apparent desire of government prosecutors to keep the Waltham case out of the bombings trial has made them come off like Tamerlan’s defense team for the Waltham case. They have worked hard to cast doubt on evidence of his guilt, as well as on any indication that the Waltham murders might be terrorism-related.

Meanwhile, the Middlesex County DA’s Office arguably has its own interest in keeping the homicide case open and unsolved. After all, if investigators had been able to conclude that Tamerlan was involved, they would have been admitting to having let the Boston Marathon bombers slip through their fingers. The Middlesex County District Attorney’s Office said in a statement that it is “actively investigating the Waltham triple homicide, including recently interviewing a material witness and identifying a new potential source of physical evidence.” It also admitted that Tamerlan and Todashev had been persons of interest in the case. Even if that evidence leads to a breakthrough, it will be too late to change the course of Dzhokhar’s death penalty case.

If the crime in Waltham was not an act of terrorism, then its victims, including my friend Erik, cannot be considered victims of terrorism. In fact, they are rarely referred to as any kind of victims at all. Instead Feigin has framed the people killed in Waltham as “drug dealers” and the bombing victims as “innocents.”

Labeling the victims as drug dealers arguably serves a couple of key purposes for the government. It helps to reinforce the lower court’s decision to preclude the Waltham murders from the marathon bombings trial. And it diminishes the significance of the Waltham murders. Three people died at the Boston Marathon finish line, including a child. Hundreds were injured and mutilated, and then an MIT police officer was killed days later. Still, three people were murdered in Waltham, too.

Forget an appeal or a Supreme Court case, the families of the men slain in Waltham have not seen a conviction or so much as an official statement confirming or denying allegations about Tamerlan’s role in the deaths.

But this isn’t about sympathy. It’s about safety. Had police vigorously pursued the culprits, it is quite possible that there would be no need for a U.S. Supreme Court hearing, appellate court ruling, or a trial. There might not have been any Boston Marathon bombings. Tamerlan might be behind bars on murder charges, and maybe no one would have heard of his younger brother Dzhokhar.

If the goal is to seek justice and closure in the wake of the bombings—let alone review failures of security—shouldn’t we be curious about what happened in Waltham? Can we truly account for this horrific attack without reconciling what happened that night on 9/11/11? Arguments to ignore this case may be strategically designed to ensure that Dzhokhar is put to death, but are they worth the cost? Ultimately that is the question the Supreme Court is being asked to resolve: How much justice can we afford to lose in the act of pursuing it?