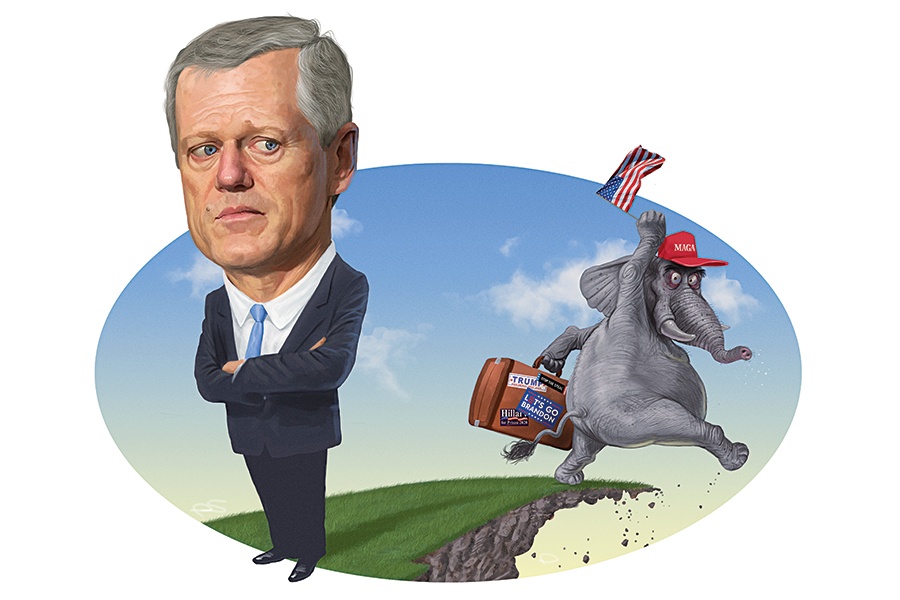

So Long, Charlie. RIP, GOP.

Last in a proud line of “Weldian” governors, Charlie Baker is leaving office for good and clearing the way within the GOP for a new breed of Trump-loving leaders. The result? The death of the state’s Republican Party.

Illustration by Dale Stephanos

DEATH NOTICE:

The Weld Republican—iconic provider of partisan balance in Massachusetts for decades—passed away on December 1, 2021. Its death was confirmed by Charlie Baker, last in the modern-day line of fiscally prudent but socially tolerant GOP governors, in an announcement that he won’t seek another term. The deceased will have held the governor’s office for 24 of the past 32 years, spurred important reforms, and provided a crucial check on Democratic rule. Visiting hours at the State House are until noon on Thursday, January 5, 2023, when the new Democratic governor will be sworn in. In lieu of flowers, memorial gifts may be given to the campaigns of future bearers of the flame, should any emerge.

Poor Charlie Baker. Heir to a generational legacy of thoughtful, civil, community-minded, results-oriented Republicans, his departure now clears the way within his party for the ascendance of dismissive Trumpian ideologues.

As the last of a breed of governors who sought bipartisan consensus not just out of expedience but as a matter of principle, Baker is now helpless to restrain the toxic partisan tide washing over the commonwealth. “That bipartisan approach, where we listen as much as we talk, where we focus our energies on finding areas of agreement and not disagreement, and where we avoid the public sniping and grandstanding that defines much of our political discourse,” said Baker as he declared himself a lame duck, “allows us to make meaningful progress on many important issues.”

A nice selfie epitaph, but it’s a vision of Massachusetts Republican governance that for now seems as dead as Baker’s political career. The exhaustion of the national Bush-era GOP establishment opened the door to Donald Trump’s toxic 2016 takeover, and now it’s Massachusetts’ turn. Baker’s departure—and the lack of a comparable successor in waiting—marks the end of a productive era in Bay State politics and the dawn of a potentially nasty new one, where paranoid, far-right GOP ideologues obsess over social issues such as gay adoption that no longer matter to the vast majority of voters here, poisoning the Republican brand for the foreseeable future. Most of the Massachusetts electorate sees Trumpism as a cancer. The demise of the Weld Republican era incentivizes many voters to seek its surgical removal.

Who has that Republican blue blood on their hands? Not the Democrats. In the pitiful tradition of a party long known for resembling a so-called “shootout in a lifeboat,” Massachusetts members of the GOP did it to themselves.

It wasn’t so long ago that things looked reasonably bright for local Republicans. There was state Senator Scott Brown’s upset win over Democratic Attorney General Martha Coakley in the 2010 U.S. Senate special election to succeed the late Ted Kennedy, fueled by independents and some townie Democrats. Baker could have beaten incumbent Governor Deval Patrick that year if state Treasurer Tim Cahill’s independent candidacy hadn’t siphoned off 8 percent of the vote. By 2014, when Baker beat the hapless Coakley in the race for governor, those voters eagerly returned to hiring a GOP bouncer to restore order on Beacon Hill. Meanwhile, Cape Cod, Plymouth County, and Greater Worcester have consistently elected Republicans to offices such as sheriff and district attorney, reflecting the enduring appeal of the Weld Republican tough-on-crime brand.

Throughout his governorship, Baker’s sky-high approval ratings have been widely seen as affirmation of the Weld Republican approach. As Joshua Miller observed in the Boston Globe, Baker was “a man who is not shaping the political zeitgeist but is in harmony with a key part of it; a pol who is neither too hot nor too cold on key issues of the day…. Baker is the Goldilocks governor: just right.” But in this newly updated version of the fairy tale, the bears tear Goldilocks limb from limb and dine on the remains. Baker’s announcement marks—as the leading expert on the subject, former Governor Bill Weld himself once told us—“the end of the Weld Republican.”

It will also be the end of the GOP governor. For the better part of the past 31 years, Massachusetts voters have hired Weld Republicans to paint with a tasteful color palette: blue on healthcare, education spending, and social tolerance, and red on crime with shades of purple on other big issues, including immigration. They provided a necessary check and balance to our overwhelmingly blue legislature. They put the brakes on spending.

Now, the last of them, Baker, the hardcore policy wonk who boasts of “managing the state’s fiscal affairs with discipline and care,” will watch from the sidelines as Democrats seek to seize virtually unchecked control of the state. Massachusetts “is in really good financial shape right now,” says former state Senator Richard Tisei, Baker’s 2010 running mate, “and you could reverse all the progress we’ve made.”

In addition to an absence of financial accountability, one-party rule serves up other ominous dangers, including the potential for a staggering lack of transparency at the State House as well as a chokehold on all legislation and policy, social, fiscal, or otherwise. Is this the future we all want for Massachusetts? Given the recent death of the Weld Republican and the state GOP’s self-immolation, it’s starting to look like we may not have a choice.

Massachusetts has not always been hostile to Republicans. As Ted Frier and Larry Overlan note in their definitive history of the state GOP, Time for a Change: The Return of the Republican Party in Massachusetts, the Sacred Cod in the House chamber once pointed to the right—signaling a Republican majority—for nearly a century, from the Civil War until a few years after the end of World War II.

Republicans were mostly in sync with indigenous strains of tolerance for religious and ethnic diversity, rejecting the nativism and racism that today define the national GOP. Even during the post-World War II Democratic ascendancy, the state GOP brand was defined by civic-minded, good-government Brahmins ranging from Leverett Saltonstall, a U.S. senator from Massachusetts from 1945 to 1967 after three terms as governor, to Frank Sargent, who served as governor from 1969 to 1975.

After Michael Dukakis succeeded Sargent in 1975, the GOP Brahmins were eclipsed by conservative followers of Ronald Reagan, the last Republican presidential nominee to carry Massachusetts, in both 1980 and 1984. Millionaire businessman Ray Shamie energized younger Republicans by swamping card-carrying Brahmin Elliot Richardson in the 1984 U.S. Senate primary. The 1986 election was a classic lifeboat gun battle in which the two leading GOP gubernatorial candidates withdrew from the race for reasons ranging from allegations of wandering nude in the office to falsely pretending to be a Green Beret. But it cleared the way for Shamie to seize control of the party and rebuild its candidate recruitment and opposition research.

By 1990, Dukakis had squandered the state’s fiscal health in service to his failed presidential campaign, and Massachusetts voters were angry. In the November elections that year, the GOP made its biggest gains in the state House of Representatives in 38 years, and also elected enough state senators to sustain a gubernatorial veto. Most important, a younger, hipper species of Brahmin—former U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts Bill Weld—squeezed past the dyspeptic Democratic nominee, Boston University President John Silber, to win the governor’s office.

The era of the Weld Republican had arrived, combining fiscal conservatism with unapologetic social liberalism. At the state GOP convention in March 1990, a speech by the staunchly pro-choice Weld was interrupted by a pro-life delegate who rushed toward the front of the stage, holding aloft his baby daughter for Weld to see while screaming, “Hey Bill, are you going to kill her, too?” Pro-life House Minority Leader Steven Pierce won the convention endorsement, only to be crushed by Weld in the primary.

Meaningful policy victories quickly followed Weld’s inauguration: the repeal of an unpopular sales tax on services, unemployment insurance reform, and major changes in the welfare system. Most telling, Weld worked in tandem with moderate Democrats in the House and Senate to pass a landmark education bill pouring money into schools while introducing two reforms bitterly opposed by powerful teacher unions: charter schools and MCAS testing. By his own account, Weld “got along great” with the building trades and was willing to take on the public-employee unions, who hated his neoconservative money-saving ideas. (Some older MBTA stations still sport faded stickers on the wall declaring efforts to cut costs by privatizing some state services “a Weld scam.”)

Weld says he chilled the ideological climate by endorsing progressive environmental and immigration policies, creating the state’s first commission on gay and lesbian youth issues, and appointing the Supreme Judicial Court Justice Margaret Marshall, who would eventually write the decision legalizing same-sex marriage. “It made everybody relax. There wasn’t a huge fight over everything,” he recalls. An added plus come reelection time: Weld’s moves resonated with suburban liberals more than public-sector union whining.

Conservative Republican discontent over this lurch leftward was mitigated by patronage hiring and an infusion of young pro-Weld activists into party operations. Weld’s lieutenant governor, Paul Cellucci, had closer ties to GOP insiders than Weld and kept the party rolling when he succeeded Weld as governor, easily dismissing state Treasurer Joe Malone’s challenge from the right in the 1998 gubernatorial primary. Even a bona-fide social conservative such as Mitt Romney claimed to be pro-choice when he won the gubernatorial election in 2002, a tribute to the enduring political power of Weldism.

Deval Patrick, running on his résumé and a few Weld-like policy positions such as developing wind power and easing the property-tax bite, interrupted the Weld Republican winning streak in 2006. With Baker’s 2014 victory, though, Weldism was restored. And despite a pandemic that put Baker’s master plans on hold and triggered politically risky shutdowns and mandates, by mid-2020 his approval ratings had never been higher, with Democratic approval of the governor regularly topping 50 percent.

Baker was also the latest governor in the Weld Republican line to treat the GOP’s more conservative activists and the party apparatus with indifference verging on contempt. The party faithful fumed as Weld stacked his administration with left-leaning acquaintances. Supporters of fringe Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul packed the 2012 GOP caucuses and won delegate seats at the national convention in an effort to embarrass presidential nominee Romney before being ejected by party leaders. “The party has been infiltrated by liberals,” declared the head of a conservative splinter group, the Massachusetts Republican Assembly, in 2013.

Nearly a decade later, Trumpism—and seven years of Baker’s unbridled disgust for it—has turbocharged local Republicans’ grievances. The lifeboat crossfire reached new heights last June when state party chairman Jim Lyons refused to condemn a far-right GOP state committee member who told a married gay Republican she was “sickened” that he had adopted children. All but one of the 30 House Republicans signed a letter calling on Lyons to denounce her. His response: “We as Republicans must not act as the far left wants us to.”

Forget safeguards against the Democrats going overboard on issues of taxation, education, and crime; the tenor of the new, Trumpified state GOP promises a future where Republicans are so tainted by far-right dogma that they can’t even get a look from most unenrolled voters. “There are definitely [people] who enjoy having that check and balance and like having a Republican in office,” says Jennifer Nassour, state GOP chair from 2009 to 2011. “But it has to be a Republican focused on the right things.”

Could that describe former state Representative Geoff Diehl? He was the GOP’s first significant entry in this year’s governor’s race. In homage to the pro-business agenda embraced by Weld Republicans, Diehl markets himself as “a leader who knows the challenges faced by small businesses [and] the impact of over-taxation and reckless spending by government.” And last spring, Diehl made a show of urging Baker-hating GOP activists to welcome a change in party convention rules so that Baker had a better chance of getting on the ballot in 2022.

Still, a few head fakes toward the center can’t hide Diehl’s flagrant fealty to the most egregious fantasies of Trumpism. On October 4, 2021, he paid his Mar-a-Lago initiation fee by claiming “the 2020 election was rigged,” even calling for a “forensic audit” of the landslide Trump defeat in Massachusetts a few months earlier.

The very next day, Trump endorsed Diehl. And a solid majority of Massachusetts GOP voters have made it clear that’s the way they like it: One poll late last year had Trump’s favorable rating with them at 81 percent; three out of four wanted a gubernatorial nominee who is loyal to Trump, and 68 percent insisted Joe Biden’s election was illegitimate. Says Weld of Diehl, “He’s made the ultimate Faustian bargain with Trump.”

He’s not the only one who feels that way. As this issue went to press, Chris Doughty, a Harvard Business School graduate and president of a large Wrentham-based metal manufacturer, and a total unknown in political circles, entered the GOP primary contest against Diehl. “He brings common sense to this race,” says his campaign strategist Holly Robichaud, a former aide to Diehl.

It would be easy for the 90 percent of us who aren’t registered Republicans to laugh off the party’s suicide, with or without schadenfreude. Call the Harbor police! Those Republicans are in the lifeboat taking target practice on each other again! But for citizens nervously eyeing the state’s ever-growing cost of living, it’s no joke. Chief among the concerns of the Weld Republican constituency is the loss of a check on Democrats’ desires to spend more, and tax more to pay for it. “You have to have somebody to take the drinks away and say you can’t do everything you want,” says Tisei, the former state senator. Under the uncontested Democratic rule of the Dukakis years, he recalls, “everybody in state government thought a certain way, there was only one way to do things, and nothing else was possible.”

Back then, even the threat of political competition exerted a check of sorts. Right-leaning Democrat Ed King skewered Dukakis-era liberalism in a 1978 Democratic primary upset, emboldening moderates and conservatives. In order to keep them on board, “Democrats didn’t do things like fight Proposition 2 ½ and press on tax policy,” recalls veteran Democratic consultant Scott Ferson of the Liberty Square Group. At least, not successfully.

After voters rewarded Weld’s first term with a 71 to 28 percent reelection landslide in 1994, it didn’t matter that Republicans no longer had enough senators to sustain a gubernatorial veto on a party-line vote. “When you have two parties that have some substantial ability to influence outcomes, you have a more full-ranging discussion about the issues and more opportunity to work toward compromise,” says former U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts Michael Sullivan, a Weld Republican who served in the House during the early 1990s.

But will that opportunity now be lost? After Ayanna Pressley’s 2018 congressional upset, Senator Ed Markey’s 2020 defenestration of Representative Joe Kennedy, and Boston Mayor Michelle Wu’s sweeping win last year, the local left is on a roll.

Power abhors a vacuum. Sullivan predicts some of the most loathed aspects of Beacon Hill sausage-making—big decisions taken behind closed doors and jammed through without roll-call votes—could become even more ubiquitous: “Little would need to be disclosed if you don’t have a vibrant opposition within the system.”

History shows us what we stand to lose. When Massachusetts Republicans choked to death on their own colic in the mid-1980s, leaving us with one-party Democratic rule, state government became a costly shitshow. Now, “The danger here is that the economic climate could be quickly harmed by a movement on the far left to view the business community as the enemy, not as a partner, in charting a course for the future of the state,” says lifelong Democrat Will Keyser, who wound up advising Baker’s campaigns.

Whether or not history repeats itself, the surrender of the local GOP to the corrosive style and hard-right substance of Trumpism delivers an immediate blow to our state’s outsize belief in our own political exceptionalism. From the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s first seal depicting a Native American begging the colonists to “come over and help us,” to the 19th-century conceit that Boston was “the Hub of the Universe,” to the post-1972 bumper stickers touting us as “the one and only” state to vote for McGovern over Nixon, to contemporary self-congratulation over trailblazing policies on universal healthcare and same-sex marriage, we’ve paraded our status as the valedictorian of American politics. A presidential cycle without Massachusetts candidates is a rarity; this past one, we had four (Weld, Patrick, Elizabeth Warren, and Seth Moulton).

Our run of thoughtful Republican governors has granted us bragging rights to bipartisanship in an era when hyper-partisanship rules. And they provided us with balance.

No longer. Those fantasies will be interred along with the Weld Republican. And that is something we should all be mourning.