Bill Russell Changed What It Meant to Be an Activist Athlete

The Boston Celtics legend leaves a legacy just as impressive off the court as on it.

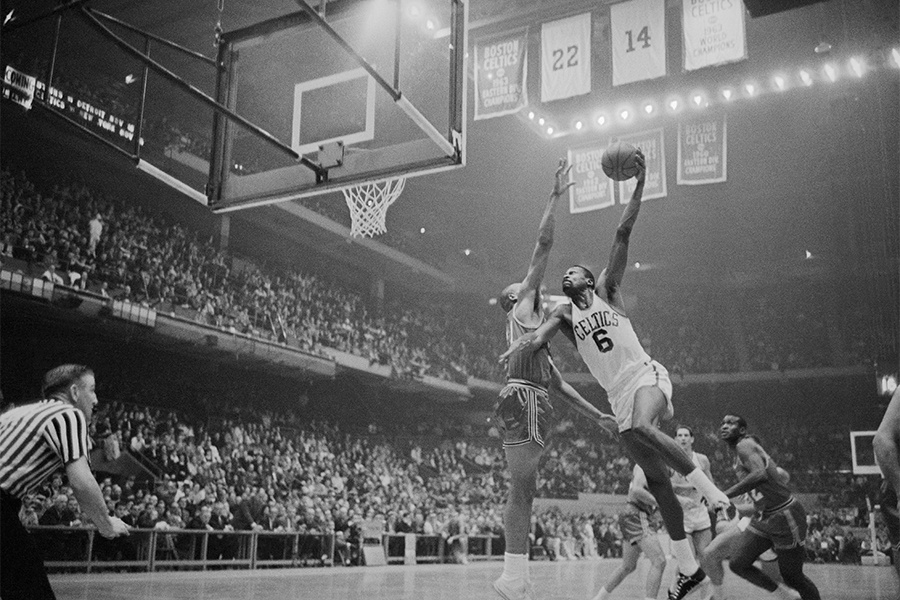

The Boston’s Celtic’s Bill Russell, (R) goes in high to score as St. Louis Hawk’s Zelmo Beaty, (L) tries to block the attempt in a 2nd person action at the Boston Garden in this photograph. Celtics won the game with 116-110. Photo via Bettmann/Getty Images

When I heard of Bill Russell’s passing, the first thing I thought of was how much recency bias and the passage of time obscured his accomplishments on the court. I stopped what I was doing, went to YouTube and watched old footage of his playing days. I watched him fly up and down the court, grabbing rebounds, initiating the fast break by not only blocking the shot but directing the ball to his teammates while they were already in motion, beating everyone down the court and finishing at the rim. I was reminded once again of Russell’s utter grace and supreme athleticism on the court. But even though his skills were undeniable, his impact on the city of Boston and on professional sports in this country as a whole is nigh-incalculable. His reach and influence extended so much farther than what he did on the basketball court. In his 88 years on this planet, Bill Russell became a trailblazer and an icon in the space of civil rights and social justice while remaining the gold standard of the activist athlete.

Bill Russell was the first Black superstar in NBA history, which meant he was going to face serious resistance no matter what city he landed in after the 1956 NBA Draft. The St. Louis Hawks had the rights to the 2nd pick, but didn’t want a Black player to be the face of their franchise, so Red Auerbach made a deal with them and brought Russell to Boston. Mind you, he had just come off back-to-back NCAA Championships with the University of San Francisco and was mere months from leading the United States to an 8-0 record in Melbourne, Australia to bring home the gold medal in basketball at the 1956 Summer Olympics. The deal wasn’t without controversy at the time—Auerbach parted with two beloved future Hall of Famers, “Easy” Ed Macauley and Cliff Hagan, to make Bill Russell a Boston Celtic. Most people thought Red had lost his mind, but they certainly didn’t think it a year later when the Boston Celtics beat those very same St. Louis Hawks in 7 games to win their first NBA Championship led by Russell, who had 19 points and 32 rebounds in the deciding game. It was the first of what would eventually be a mind-boggling 11 championships for the team as led by Russell.

But no matter the highs of his professional playing career, Russell suffered indignities and poor treatment due to the fact he was the Black face of a sports franchise. He dealt with racism, whether here in Boston or on the road. I remember as a kid hearing about how he was denied even being sold a home in Wellesley while leading the Boston Celtics to multiple NBA championships. He ultimately ended up in the nearly all-white suburb of Reading, but not without encountering a near-insurmountable level of resistance. For those of us who grew up in Boston with his legend, though, he was a hero. I was raised in the South End and Lower Roxbury, the home of the city’s most prominent activists, freedom fighters, and civil rights leaders, so Bill Russell was simply another local champion for social justice we all looked up to and hoped to emulate as adults.

And though he may have been one among multiple titans of social justice here, he was still larger than life. For one thing, he wasn’t one to hold his tongue or mince words, and he was an active participant and leader in the civil rights movement. He attended the March on Washington, and he immediately traveled to Jackson, Mississippi after the assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers to lead the first ever integrated basketball camp in the state’s history. He was also front and center supporting Muhammad Ali when he refused to be drafted during the Vietnam War. His activism wasn’t only national, either. When Mel King led protests following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. demanding affordable housing in Boston’s South End and Lower Roxbury neighborhoods, Bill supported him and the other protesters by bringing them free food from his nearby restaurant, Slade’s. The protests led to the opening of the Tent City Apartments on Dartmouth Street.

Even on the court, his activism was clear. He refused to reward fans who shouted racist epithets during games with autographs, which was met with further hostility. When his name was called before games, he didn’t jog out onto the court like the other players did—he walked to the center line and crossed his arms as an act of defiance. He spoke up against injustices and inequity on a regular basis, both in the world of sport and beyond it. To him, he was doing what he thought was right and just, but to spectators and critics, he was an arrogant, uppity, self-important athlete, even as he was fighting for everyone’s fair treatment and equal protection under the law.

Russell was particularly beloved in inner city Boston neighborhoods like the South End, Roxbury, and Dorchester where the Black and Latino population was concentrated. Even though he hadn’t played a game in a Celtics jersey in over a decade while I was growing up, elders and older kids spoke his name on the stoops, at the basketball court, and the arcade so frequently you’d think he was still on the roster. The highest praise that could be heaped on my shoulders as the tallest kid on the court playing center against my peers was if the grown ups watching called me “Little Bill Russell.”

But he never truly felt appreciated by white Bostonians during his playing career, to the point that he was uninterested in having fans attend his jersey retirement ceremony at Boston Garden on March 12,,1972, even after being the player that made the Boston Celtics the greatest franchise in NBA history. It wasn’t just racist fans that made Russell’s playing days hard here in Boston—he also endured a great deal of unwarranted animosity for being outspoken, uncompromising, and unapologetically Black during his playing career. It’s not an exaggeration to say he’s the reason that Black sports superstars in Boston like Jim Rice, Paul Pierce, Kevin Garnett, David Ortiz, Mookie Betts, Jaylen Brown, and Jayson Tatum can be beloved in that very same city many years later.

When I think of Russell, what one man managed to do on the court and off of it, I think about how he made everyone rethink what it meant to affect change in the world as a professional athlete. And for someone who has been a Celtics fan all his life, through thick and thin, through good teams and bad, and who knows all too well what some of the worst of the fans can be like, I look at situations when the fandom is critical of a player both inside TD Garden and on social media, and thank the heavens real time social media didn’t exist during #6’s career in kelly green.

But even without it, the city of Boston didn’t exactly reciprocate the love during the career of the greatest winner in the history of team sports. The recent announcement that the NBA will retire that #6 across the league is long overdue—and also a concrete acknowledgment of Bill Russell’s impact as a champion of civil rights, a humanitarian, and a lasting symbol of leadership.