The Secret Life of Cohasset Con Man Brian Walshe

Friends and neighbors from the Back Bay to the South Shore thought Brian Walshe was a decent husband and a fun-loving guy. Then his wife Ana disappeared—and police discovered his search history.

Photo illustration by Benjamen Purvis

On January 4, Cohasset police officers drove down a long, rocky driveway to check on a woman named Ana Walshe. The gray Colonial with a large, red-brick chimney and a pool in the backyard was quiet. From the outside, they saw no signs of life.

None of Ana’s colleagues at Tishman Speyer in Washington, DC, where she commuted each week for her job at the real estate firm, had seen Ana since before the holidays. She hadn’t shown up at her desk on January 3 and wasn’t answering her phone. Her frequently updated Instagram account, filled with inspirational quotes and glamour shots of the petite brunette in designer clothes, had also gone silent. Concerned when Ana didn’t come in the next day, the company called her husband, Brian Walshe, who said he hadn’t seen her, either. Concerned, Tishman Speyer’s head of security dialed the cops.

The Walshes’ home sits snugly in the suburbs, less than two miles from Cohasset’s charming downtown, and is set back in the woods behind Chief Justice Cushing Highway. A small used-car dealership is around the corner, with a Stop & Shop just a two-minute drive away. When police arrived, Brian answered the door. With his long, dark hair swept back, he said he hadn’t seen his wife since the pre-dawn hours of New Year’s Day, when she rose from their bed and left the house in an Uber or a Lyft, heading for Logan to catch a flight to DC for work.

Police tried to piece together what they could. On New Year’s Day, Brian told them, he’d made breakfast for the couple’s three boys, all between the ages of two and six, before heading to Swampscott to run errands for his mother at CVS and Whole Foods. The next day, he said, he left the house just once to take his son for ice cream. By the time officers drove away, Ana was considered missing.

Two days later, investigators were still seeking answers. At a press conference, Cohasset Police Chief William Quigley announced that there was no evidence Ana had ever gotten into a rideshare on New Year’s morning, much less on a flight. Perhaps, Quigley told the public, the busy working mom “just needed a break. We just need a call from her or someone who has talked to her.”

Waiting anxiously for news, the couple’s friends—many of whom were regular members of Boston’s high-end restaurant scene, where Brian was known as a lavish spender—buzzed with speculation. One theory was that Ana had jetted off to a fabulous island somewhere and was waiting for her husband, who’d landed in some legal trouble related to his business dealings, and boys to join her. No one suspected foul play.

In no time, search-and-rescue efforts launched into action. Cohasset police converted the Stop & Shop parking lot into a mobile command center while K-9 officers with dogs trampled through the trees and dry brush near the Walshes’ house, searching for Ana. Divers submerged themselves in a nearby frigid stream, and helicopters buzzed overhead. Meanwhile, television trucks lined the street near the Walshe home as reporters fanned out across the neighborhood knocking on doors. Media coverage spread like wildfire, even reaching Ana’s native country of Serbia.

As police continued to investigate, a picture of Brian began to emerge. Detectives pored over hours of grainy security footage from the CVS and Whole Foods in Swampscott, where Ana’s husband said he’d been on January 1. They didn’t spot Brian. They did find evidence that he’d bought ice cream for his son on January 2, but it wasn’t the only time he’d left the house. Police also found surveillance footage of Brian, clad in a mask and gloves, at Home Depot that day, buying mops, brushes, tape, a Tyvek suit with boot covers, goggles, buckets, baking soda, and a hatchet—all in cash. When officers searched Brian’s basement, suspicions grew with the discovery of drops of blood and a bloody knife. On January 9, just five days after Ana was reported missing, police charged her husband with obstructing their investigation by lying about his whereabouts after she vanished. When authorities led Brian in handcuffs out of the courthouse in Quincy, he smiled broadly for the TV news cameras.

Screenshot from NBC10 Boston

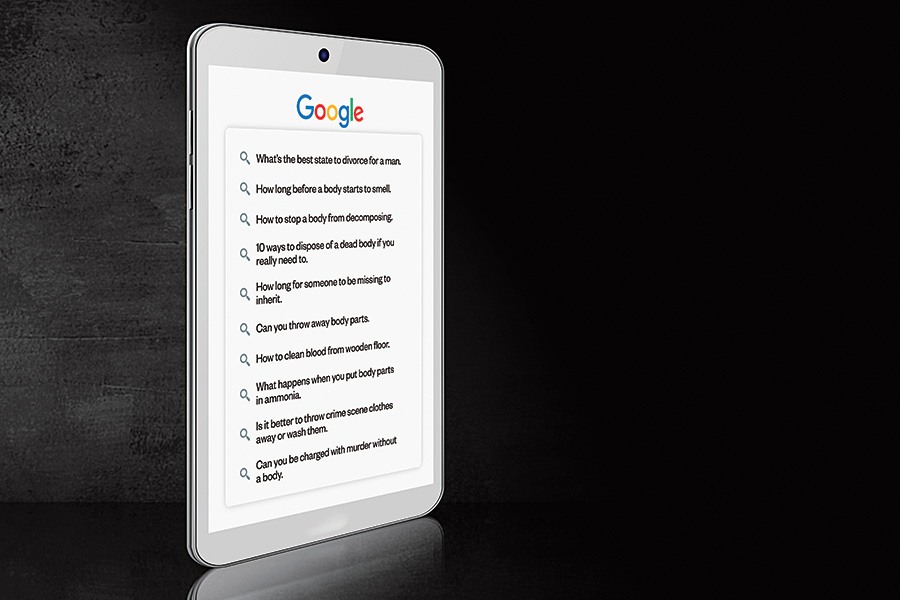

Soon, more clues surfaced. Ana’s body was still nowhere to be found, but surveillance cameras had caught Brian straining under the weight of heavy garbage bags that he disposed of in dumpsters at apartment complexes in Abington and Dover the day before his wife was reported missing. Authorities were unable to recover the trash bags from either facility. Brian, according to prosecutors, also drove to his mother’s housing complex, where he unloaded more bags in another dumpster. These bags were later recovered by investigators, searched, and found to contain items including a Prada purse, a portion of a necklace seen worn by Ana in previous photos, and the Hunter rain boots she was last seen wearing. Both Ana’s and Brian’s DNA were detected on the objects. Brian’s Google search history didn’t do him any favors, either. From his son’s iPad, he’d queried:

How long before a body starts to smell?

Hacksaw best tool to dismember.

Dismemberment and best ways to dispose of a body.

How long for someone to be missing to inherit?

Three days after Brian’s initial arraignment, Cohasset residents—bundled up in scarves and cupping candles in their hands—gathered on the town common to pray for Ana’s safe return, struggling to comprehend what might have happened. “Murder is so far out of his character,” said Brian’s former best friend, who asked not to be named for privacy. “At worst, he could throw a tantrum, but he wasn’t violent.” In fact, friends say, they hadn’t seen any signs of marital strife between the Walshes, even on the night before Ana disappeared. Could he really have fooled them all?

The town’s prayers for Ana’s safety went unanswered. Less than a week later, police charged Brian with murdering his wife.

Friends said they hadn’t seen any signs of marital strife between the Walshes, even on the night before Ana disappeared. Could Brian really have fooled them all?

In early 2010, Brian glided from table to table as though he were the father of a bride at a wedding inside the sumptuous art deco dining room of Sandrine’s French bistro in Harvard Square. Over the din of conversation and the gentle clinking of silverware, he checked in with his guests, who were savoring the tasting menu and wine pairings that he and renowned chef Raymond Ost had spent days fussing over together. The guest list that night had been carefully curated, as it had been time and again over the years whenever Brian threw dinner parties at Boston hot spots such as Select Oyster Bar, Puritan & Company, Deuxave, and Boston Chops, as well as suburban favorites Bistro 5 and A Tavola. Toward the end of the meal, a hush settled over the room before Brian, the master of ceremonies, introduced Ost and his kitchen crew to one ovation after another.

Brian had long sought to make a name for himself among the city’s top restaurateurs, wanting to be known as a whale, or a big-ticket patron—and he often succeeded. One former friend in the restaurant industry (who asked not to be named for privacy) recalls meeting Brian the same night Brian ran up a $6,000 tab at the restaurant where he worked. When it came time to settle the bill, the friend says, Brian had credit card trouble and was unable to pay. He left his Breguet watch as collateral and returned the next day and paid his tab in cash, adding an extra $2,000 to smooth things over. Another time, the friend says, Brian took them to dinner at Charlie Trotter’s in Chicago and bought a $25,000 bottle of wine. “He insisted on having chef’s tasting menus everywhere he went, regardless of whether it was even offered,” says the friend. Then there was the time, the friend recalls, when Brian ordered Deuxave’s entire inventory of truffles in a feat so outrageously decadent it was memorialized by local food writers.

View this post on Instagram

Brian didn’t stand out only for his spending, but also for his worldly air and sophistication. He knew a lot about wine and art, and no one in his social circle could mention the name of their next vacation destination—no matter how far-flung or obscure—without Brian offering travel advice, hotel recommendations, and, of course, restaurant suggestions. He also seemed able to secure near-impossible reservations, jetting off to dine at Copenhagen’s Noma, widely considered the world’s best restaurant, and a Noma pop-up in Tulum, Mexico.

Even as Brian wanted to be known, he didn’t let many people know much about him. He often told people that he was wealthy and Persian. He also let on that he owned a home at 225 Beacon Street, a five-story, 6,000-square-foot brownstone. He’d often meet friends outside, ahead of an evening on the town, and later see them off from his stoop before entering his home’s glass vestibule. He never entertained in any of his residence’s multiple ballrooms, nor did he ever throw a dinner party there. In fact, with one or two rare exceptions, the close friend from the restaurant says, Brian never let anyone inside.

The source of Brian’s wealth was also a mystery. When asked, his explanations were often varied and vague. According to former friends, Brian said he dealt in art. He also claimed that he and a college roommate had sold an airline ticketing service to Expedia for close to $200 million when he was in his twenties. At other times, he said he made his money off the oil fields of Papua New Guinea and the Yucatan peninsula. His moniker among acquaintances, according to the restaurant friend, was aptly “international man of mystery.”

Behind the enigma, though, was less than met the eye. Brian didn’t own the fabulous brownstone at 225 Beacon, despite what he’d told his friends. His mother, Diana, held the deed to the home, and she allowed him to live there with her. And as much money as he spent around town, his former friends say, Brian was seen bouncing checks and having trouble with his credit cards. “He borrowed money from a lot of people,” Brian’s former best friend says, adding that Brian often blamed his accountants and money managers for his financial woes. “He was always buying time.”

Still, not everyone in Brian’s orbit bought his act whole cloth. “I sensed an emotional neediness behind the extravagance and expense,” says Amy Traverso, the senior food editor of Yankee Magazine, who was among those invited to Sandrine’s in 2010. “The evening was a production, and Brian very much needed to be the center of attention, the person everyone had to thank.”

That need for attention may have been rooted in a troubled childhood, people close to Brian say. He told friends that his mother and father, Thomas Walshe, a neurosurgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, were physically and emotionally abusive to him while growing up. “According to Brian,” says his restaurant friend, Brian’s “father was particularly abusive, beating the shit out of him and telling him he was a loser.” Ana echoed this in a letter of support she filed on her husband’s behalf in a court case involving Brian’s business dealings. “A deep feeling of shame governed his life,” she wrote. “He was taught to lie and hide. He was told that he was a loser, that his parents should have not had him, that he had no chances of making anything of himself in life, and that he was a lost cause.” According to a sworn affidavit by his father’s close friend, Brian even spent time in the Berkshires at a psychiatric hospital, where he was “diagnosed as a sociopath.” (Sociopath is not an official psychiatric diagnosis, but is often used colloquially to refer to someone who has an antisocial personality disorder, which is characterized by a disregard for others, a lack of empathy, and dishonest behavior.) At the same time, “being accepted by others was survival for Brian,” his former best friend said, adding that money wasn’t Brian’s endgame but rather something he used in order to build relationships and buy acceptance. “It was all pay-to-play for him.”

There was one thing Brian told people about himself that was true—at least, almost. He claimed that he often dealt in art. He just didn’t mention it was art forgeries.

There was one thing Brian Walshe told people about himself that was true—at least, almost. He claimed that he often dealt in art. He just didn’t mention it was art forgeries.

On a sunny November day in 2016, Brian was seated at a table in a well-appointed lounge inside the Four Seasons Hotel, two paintings tucked inside his designer bag, waiting for the assistant of a Los Angeles gallerist to arrive. Earlier that month, Ron Rivlin of L.A.’s Revolver Gallery, which holds the world’s largest gallery-owned collection of Andy Warhol pieces, noticed an ad on eBay that Brian had posted. It read, in part, “We are selling 2 Andy Warhol paintings from our private collection…only because we need the money for renovations to our house. Our loss is your gain.” The ad claimed that the true auction value of the pair of paintings was anywhere from $120,000 to $180,000 but that he was merely asking for $100,000—and doing so on eBay, of all places—because Christie’s was unable to auction them until the following spring. Included in the ad were photos of the Warhol Foundation authentication stamps and pictures of the works.

Rivlin called Brian and agreed to pay $80,000 in cash for the art. Satisfied that the paintings were genuine, Rivlin wanted to know if the seller was, too. He asked Brian to forward an image of his Massachusetts driver’s license and then Googled the listed address: 225 Beacon. When Rivlin saw that the home was worth an estimated $6.6 million, he exhaled. Brian seemed to check out. Soon after, Rivlin dispatched his assistant to Boston with an $80,000 cashier’s check in her bag and strict instructions: “I told her,” Rivlin recalls, “‘Examine the canvases and then step away and call me with your impressions.’”

View this post on Instagram

Inside the Four Seasons, after Brian pulled the paintings out of his bag, Rivlin’s assistant called her boss. She explained that she couldn’t examine the authentications on the back of the artworks because the paintings were in frames that were screwed on tight. “He’s a really cool guy,” Rivlin recalls her saying. “He’s dressed nicely, and the paintings were in a Prada or Gucci bag.” Rivlin told her to execute the deal, package the paintings, and return home. By the time Rivlin’s assistant landed at LAX later that day with her precious cargo in tow, Brian had already deposited the cashier’s check.

The following morning, Rivlin eagerly unwrapped his new paintings. Then his heart sank. The color was off. When he unscrewed the frames, he saw there were no authentications affixed to the back and the canvases had strings hanging off them, a tell-tale sign that they’d been freshly cut. Rivlin knew he’d been had.

He quickly grabbed his phone and dialed Brian. There was no answer. Rivlin called again. No answer. Rivlin fired off a text. Still no reply. In all, Rivlin tried to contact Brian 16 times over the next few days in vain. Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, Brian had paid off $24,900 in credit card bills.

A week later, Rivlin finally received an email from Brian in which he promised to pay the gallery owner back. Yet over the next several weeks, court records state, Brian made excuse after excuse for why he hadn’t refunded the money, including that he was having trouble with his bank. In the end, Brian transferred $30,000 to Rivlin—a small portion of what he owed—followed by more excuses. When the rest of the money never came, Rivlin called the FBI.

The federal investigation took nearly a year and a half, but the law finally came for Brian. On a spring day in May 2018, FBI agents walked up to the Walshes’ recently refurbished industrial loft in Lynn, where Brian and Ana had moved from Boston, and raided the home. Soon after, prosecutors indicted Brian on charges of wire fraud. Authorities fitted Brian with an electronic-monitoring ankle bracelet as a condition of his pretrial probation.

When the legal dust settled, Brian’s business model became clear: For more than five years, he had been running a scam. It had all started, according to court records, on a 2011 trip to South Korea, where he’d convinced his college friend’s family to give him three Andy Warhols, two Keith Harings, and a Chinese statuette, plus all of the paperwork proving their authenticity. He’d assured the family that he could sell the artworks on their behalf. When Brian returned to the United States, he hired a skilled New York–based forger to copy the Warhols. From there, Brian orchestrated a classic bait-and-switch operation: He showed buyers the originals and the paperwork and then sold them the fakes. He ran this scam numerous times on two different continents until the feds finally caught up with him. If found guilty, Brian would have to pay nearly a quarter of a million dollars to his victims in restitution and return the original paintings to their Korean owners. Even worse: He was facing jail time.

To his friends, Brian’s life seemed to be unraveling. Just weeks after being indicted, he met with his buddy who worked in the restaurant industry and talked to him for more than four hours. According to the friend, Brian confessed that he was not an art dealer, as he had told people, but rather an art swindler and that he was in legal trouble. As the friend recalled, “Brian said, ‘Everything about me is made up.’”

Brian Walshe during his January arraignment at Quincy District Court. / Photo by Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe/AP

It didn’t take Brian long to find a new potential source of income. In typical fashion, though, it would require yet another illusion. In September 2018, court records state, Brian learned his father had died while on a trip to India. A few days later, he and Ana pulled up in front of Thomas Walshe’s charming oceanfront home perched just north of Nantasket Beach and parked in the brick driveway. They walked up the salt-weathered front steps to the front door and let themselves inside.

According to court records, there were papers on the middle of Brian’s father’s desk labeled “Will of Thomas M. Walshe III.” The document had a single line that referred to Brian, his only child and heir apparent. It read: “I hereby bequeath to Brian R. Walshe my best wishes but nothing else from my estate.”

It wasn’t much of a surprise: Brian had been estranged from his father for more than a decade, after his father had accused him of swindling him out of nearly a million dollars from a real estate deal gone bad. According to an affidavit from a close friend of Brian’s father, the disinheritance was consistent with the elder Walshe’s desire to remain estranged from his son. In essence, it was payback.

Still, by all accounts, Brian wasn’t ready to accept his dad’s decision. In court records, he denied that he’d ever seen his father’s will, and soon after his visit to Thomas Walshe’s house that day, he filed paperwork in Plymouth County petitioning the court to name him, as his father’s only child, the sole representative of his father’s estate in the absence of any will. By December 2018, the court agreed.

On the first business day of the new year, according to court filings, Walshe approached a Santander Bank branch and drained his father’s account of the $76,488.04 in it. Later, Brian logged onto his computer, uploaded photos of more than 100 of his father’s prized belongings, and posted an ad online for an estate sale. He listed Merona glass, Persian rugs, art deco platform beds, china, and Asian art, before ending the estate sale ad with, “BONUS CAR FOR SALE Large amount of jewelry just discovered will post pictures soon!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!”

By the time the doors of 909 Nantasket Avenue opened in late January, the bargain hunters were ready. They looked over the jewelry, ran their fingers over the Persian rugs, and scanned artwork for authenticity before opening their wallets. Brian had hit pay dirt. What Brian didn’t know was that Jeffrey Ornstein, his father’s close friend, had been to the elder Walshe’s house before Brian, spotted the will, and—not trusting his dear friend’s only son—taken a picture of it. Ornstein went to the authorities and, according to court documents, on February 2020, the probate court declared that Ornstein’s photograph of Thomas Walshe’s will was valid.

One year later, Brian pleaded guilty to charges related to the art forgeries case and was placed on house arrest until his formal sentencing. It seemed as though he might elude jail time, but on August 2021, just before Brian was to learn if he’d be sentenced to prison, the prosecution caught wind of the alleged destruction of his father’s will and the liquidation of assets from his father’s estate. If proven in court, these actions would not only have constituted a violation of Brian’s pre-sentencing probation but could have also landed him back before a criminal judge to answer for a fresh set of fraud and embezzlement charges. Prosecutors asked for a postponement of the sentencing hearing to give the government time to investigate.

Walshe had fooled people about his wealth, his profession, and his inheritance, and he was finally suffering the consequences. At least, though, he still had Ana.

Ana Walshe pictured at a 2021 outing with her former employer, the Mutlu Group; just over a year later, her husband would be charged with her murder. / Photo by Stephen Sherman Photography

The last night she was seen alive, Ana appeared to be happy. On that unseasonably warm New Year’s Eve, she and Brian gathered around their kitchen counter at home in Cohasset with their dear friend and Ana’s former boss, Gem Mutlu, to ring in 2023. The dinner Brian had painstakingly prepared bubbled away in the kitchen while the Walshes’ three sons played. A note, written in lipstick-red ink on a box of Lanson Noble Cuvée, presaged a bright future for the couple: “Let’s make 2023 the best one yet! We are the authors of our lives…courage, love, perseverance, compassion and joy. Love Ana.” Mutlu later told reporters that nothing seemed out of the ordinary that night between Ana and the man she said she’d loved since the moment she’d laid eyes on him.

Ana met Brian in 2008 at the Wheat-leigh hotel in Lenox, where she was working as a reservations manager. At the time, she was married to a chef who had previously worked at the Inn at Little Washington in Virginia, where she had her first job as a housekeeper and server after emigrating from Serbia. Next, the couple moved to Lenox to work at the Wheatleigh, and then after two years moved south again to work in DC, where she ascended from an assistant front-office manager at the Willard InterContinental Hotel to front-desk manager to front-office operations manager.

As she climbed the professional ladder, Ana stayed in touch with Brian. In 2013, she began dating Brian, according to friends, and her divorce was finalized the following year. “She was head over heels for Brian,” says Ana’s longtime friend from Washington, DC, Carrie Westbrook. “Brian was flashy and showy, and that’s what Ana liked about him. He appeared to embody the things she wanted. It was almost like she had a mental vision board for the house, cars, family, and lifestyle she wanted, and she thought he could provide it.”

The couple spent much of 2013 and 2014 crisscrossing the globe, staying in high-end hotels, and in December 2015, they tied the knot: Ana wore a strapless white gown and veil while Brian donned a black tux during an intimate wedding ceremony at Boston’s L’Espalier. They held a small reception at the InterContinental, where Ana was now director of the front office. By then, Ana had left behind her life in DC and moved in with Brian and his mother at 225 Beacon. In July of the following year, the newlyweds welcomed their first child. They named him Thomas, after Brian’s father.

View this post on Instagram

The Back Bay brownstone had more than enough space for the young family plus Brian’s mother, but it proved too small to contain both Ana and her mother-in-law’s strong, and sometimes clashing, personalities. In the fall of 2016, Westbrook says, Ana insisted that—for the first time in Brian’s life—he leave the nest and his swanky address behind.

Over the next several years, Ana built a real estate portfolio of homes the couple would either flip or rent out. After moving to Lynn, they bought a place in Marblehead before moving on to yet another exclusive address: Jerusalem Road in Cohasset. Ana’s career aspirations continued to rise. After demonstrating her prowess with real estate, she changed careers and took a job with Gem Mutlu at the Mutlu Group, which specializes in high-end homes.

The perception among neighbors in Cohasset was that Ana was more impressive than Brian. “Everyone seemed to think Ana was the sharper and more together of the two,” says one neighbor, who asked not to be named for privacy. This was also before any of them knew about his legal troubles.

From the outside, the Walshes appeared to have everything they wanted. Soon, though, Ana began to complain about her domestic situation, albeit not her marriage, Westbrook says. Wanting to return to DC, Ana took a job at Tishman Speyer, sold the Jerusalem Road house in five days for $35,000 over asking price, and bought a home in the tony Chevy Chase neighborhood of DC. Brian and the boys, meanwhile, moved into a rental home in Cohasset, where Ana spent her weekends before traveling to DC for the workweek, waiting for Brian to resolve his legal woes so that he and the boys could join her in their new home.

The commute and the distance from her family began to wear on Ana. Other than that, though, few people knew of trouble in their marriage. But there was a history of trouble that preceded Ana and Brian’s wedding. When they were dating and Ana was living in DC, she reported to police that her boyfriend from Boston had threatened to kill her and her friends. (She never named Brian and never pursued formal charges.) In 2014, meanwhile, she said that Brian abused her: In a text message to Brian’s close restaurant friend (which Boston viewed), she complained that Brian “is violent with me.” (Brian Walshe’s lawyer, Tracy Miner, declined to comment on the text and declined requests for an interview with either her or Brian, who has pleaded not guilty to the murder charges.) There was also a cryptic but desperate text message that Ana sent to her mother just a week before New Year’s Eve, asking her to come to Boston at once. A few days later, Brian typed into Google: “What’s the best state to divorce for a man.”

By the time New Year’s Eve rolled around and Mutlu joined the Walshes for dinner, though, it was all smiles, laughter, food, fine wine, and heartfelt wishes for a bright future from a happy-looking couple. Hours later, Brian’s wife disappeared forever.

First published in the print edition of the May 2023 issue with the headline “The Secret Life of Brian Walshe.”