This 121-Year-Old Boat-Making Company Combines Passion with Innovation

Maine-based Old Town Canoe builds handcrafted vessels along the Penobscot.

Photo by Greta Rybus

The team at Old Town Canoe really, really wants to get you on the water. “Our brand statement is ‘Adventure lives here,’ and that’s [truly] our banner—unplugging from everyday life and plugging into watercraft that let you reconnect with nature,” says Ryan Lilly, the boat-building company’s brand manager. And with more than a century of experience to its name, the Maine-based outfit offers consumers plenty of options to plug into: canoes and kayaks for rafting, hunting, tripping, fishing, and relaxing, plus the paddles and life jackets to go with them.

It helps that most of the company’s employees are water enthusiasts themselves. “Nearly everybody that works for us uses our products on a regular basis,” Lilly says. That means Old Town knows just what its customers need in their boats—a place to secure fishing rods; extra-durable hulls for traversing rocky rivers; space to fit a dog—because the people designing, building, and promoting the boats live and breathe the company’s creed.

With its sister company, Ocean Kayak, Old Town produces about 100,000 boats per year. / Photo by Greta Rybus

A worker adds the storage hatch to a kayak on the assembly line. / Photo by Greta Rybus

Applying Old Town graphics, a worker preps a kayak mold for use. / Photo by Greta Rybus

And that’s really what Old Town is about: authenticity. Like many of Maine’s artisan-focused companies, heritage plays a part in every aspect of the business. The Gray family started the operation in 1898, in Old Town, Maine, along the Penobscot River. When the river froze over that winter, the Grays enlisted out-of-work loggers to build wood-and-canvas canoes, and by the following year, a booming craft business was born. More than 100 years later, although the owners have changed (Johnson Outdoors bought the company in the 1970s) and the product offerings have diversified, the made-in-Maine-by-Mainers song remains the same. “We have many employees who are multigenerational; their parents and their grandparents built parts for our boats,” Lilly says. “The company is so interwoven with the community.”

The boat-building company prides itself on its innovative designs, including the “Discovery 119 Solo Sportsman,” a new hybrid canoe-kayak model. / Photo by Greta Rybus

Inserting a jig into a newly formed boat helps the vessel maintain its shape during the cooling process. / Photo by Greta Rybus

Yet for all of its nods to the past, Old Town keeps one oar sunk firmly in the future. Research and development is a cornerstone of the brand’s business model. Thanks to a 3-D printer, Old Town can design, print (in foam), test, tweak, and retest model boats before sending them to market. “We’re usually working a year and a half, two years out on the next product to keep our pipeline full,” Lilly says. That proactivity means the company often sets the industry standard for innovation, putting out products such as pedal-driven kayaks (similar to a recumbent bicycle, but on the water), and snagging awards along the way. “It’s pretty awesome to have such a [rigorous] research-and-development side,” Lilly says.

Once a boat design gets a greenlight, Old Town makes it using one of two processes. The first, rotational molding, or roto-molding for short, results in single- and triple-layer watercraft, such as the “Penobscot” and “Discovery” kayaks. The other, thermo-forming, is used for just one product line: the “Saranac” canoes. For roto-molding, workers take a bisected boat mold (split “like a bagel,” Lilly says), and fill each half with a plastic resin powder. They put the halves together and stick them in a giant oven, which oscillates to distribute the melted plastic throughout the mold. That takes 20 to 35 minutes, after which the molds cool for the same amount of time. Workers then remove the newly formed boats from the molds and toss them into an on-site tank to see if they float properly.

Once a boat passes the float test, workers start screwing in seats, rudders, bungees, and other riggings. / Photo by Greta Rybus

During its busiest season, the company operates three production shifts a day, seven days a week. / Photo by Greta Rybus

A staffer pours plastic resin powder into a boat mold. / Photo by Greta Rybus

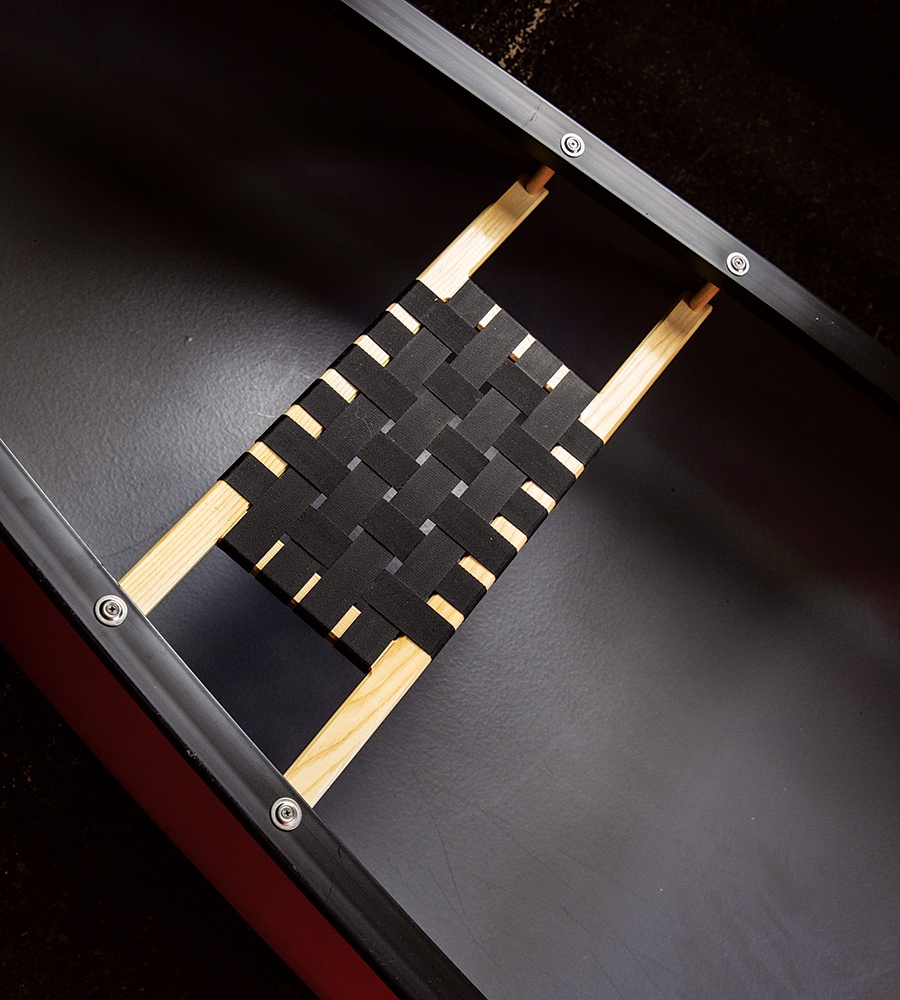

If there are no cracks or holes, the boats go into the production lines, where staffers trim the edges to remove any extraneous resin (which they reprocess for future use) and then kit out the boats according to their models. They’ll rivet a vinyl gunwale along the top; affix deck plates on the bow and stern to keep the corners together; screw in the braces that run from one side of the boat to the other; and screw in the seats, bungees, and rudders if needed. A lot of the inserts are melted in place during the roto-molding process, Lilly says, so workers screw items into a receiving end that’s already part of the boat.

With its sister company, Ocean Kayak, Old Town puts out about 100,000 boats a year from their shared facilities. Those boats go to water enthusiasts all over the world: Florida, New Zealand, Canada, Texas—“wherever you’ve got a lot of great water recreation, you’ve got a lot of our canoes and kayaks,” Lilly says. And because Old Town’s been around for so long, he adds, many generations of people have had the chance to experience its products—which is exactly what the company intended. “Whenever I talk to people about what I do for work, they’ll say, ‘Oh, I grew up going to my grandparents’ and they always had their Old Town canoe.’ It’s just that staple,” Lilly says. “There are a lot of fond memories that people have from our products. It’s pretty awesome.”

“Adventure lives here” is Old Town’s brand statement. “Our boats are all about getting our consumers on the water experiencing what they love to experience,” Lilly says. / Photo by Greta Rybus

Old Town ships boats everywhere from North America to New Zealand. / Photo by Greta Rybus

A nylon-web canoe seat, riveted into the gunwale. / Photo by Greta Rybus