Behind the Scenes at Necco

Photo by Olga Khvan

Necco Wafers. Mary Janes. Sky Bars. Canada Mints. Candy Buttons. Those inimitable staples of the Valentine’s Day classroom exchange, Sweethearts, which celebrate their 150th anniversary this February. All of these, some of the world’s most beloved and recognizable confections, have been produced by The New England Confectionary Company (or: Necco) for over a century. It’s the second oldest, continuously run candy company in the country, a feat topped only by Ye Olde Pepper Candy Companie in Salem. Necco’s products have been around long enough to have experienced some of the first Antarctic expeditions into the South Pole with Richard Bryd, and allegedly, even the battlefields of the American Civil War.

But don’t call them “nostalgic.” New president and CEO, Michael McGee, hates that word. Instead, the new head of Necco—who looks like Andrew Zimmern, if only the glabrous Travel Channel host preferred French cuffs and sleek Oakley frames—favors descriptors like “distinctive,” “traditional,” or even better, “emotional.”

“Candy is a very emotional category,” McGee says. “The holidays are a very emotional, permissible timeframe where people celebrate and treat themselves. They entertain. They gift. At Valentine’s Day they tell people they love them. And we have products that fit into all of those occasions. They like it from a taste standpoint, but there’s lots of memories attached to candy: When they tried it for the first time and who shared it with them. So, that’s why you see consumers using emotional words when describing candy.”

Built on the foundation of Oliver Chase’s ground-breaking lozenge cutting machine in 1847, an innovation that not only gave the world the Peerless Wafer (a precursor to the now famous Necco Wafer), but helped jumpstart the entire American candy industry—Necco has now been able to survive The Great Depression, both World Wars, and the effects of the Great Chicago Fire during the Chase’s brief outpost in Chicago. Part of that can be credited to Sweethearts, those chalky little love letters that still account for 15 percent of Necco’s business. But like conversation hearts, which annually discard dated expressions for more contemporary idioms like “LOL,” “#Love,” and “143,” the company has shown an uncanny ability to adapt.

Before the advent of high fructose corn syrup in, well, just about everything, Boston was the hub of candy production in the U.S. due to its ports and sugar refineries. But while Schrafft’s, Walter Baker & Company, and Rochester’s Fanny Farmer continued to compete in the dying generics market, Necco took a hard look at their future and scaled back to the essentials.

“Necco was a company like E.J. Brach’s, where we made everything: Jordan almonds, jelly beans, Boston baked beans, all kinds of things,” says Jeff Green, vice president of research and development. “I think it was the complexity of operating a business like that with a myriad of products, even just on the purchasing end, that finally did them in. I mean, when was the last time you saw a Jordan almond? It’s things like that which made those companies dinosaurs. Hershey’s makes a lot of stuff, but it’s all individual discreet businesses. There’s a Twizzlers factory. There’s a Reese’s factory. And that’s all that they do in those places. They don’t have these kind of mishmashes anymore.”

A Necco employee making Haviland malt balls for Easter. Photo by Olga Khvan

Green credits Necco’s acquisition in 1963 by UIS, Inc.—which he calls an “industrial syndicate or holding company”—from a fate similar to Scrafft’s, which was folded into PET Milk (now mostly a part of General Mills), its iconic Charlestown factory turned into commercial office for Telemundo, Mary Kay, and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

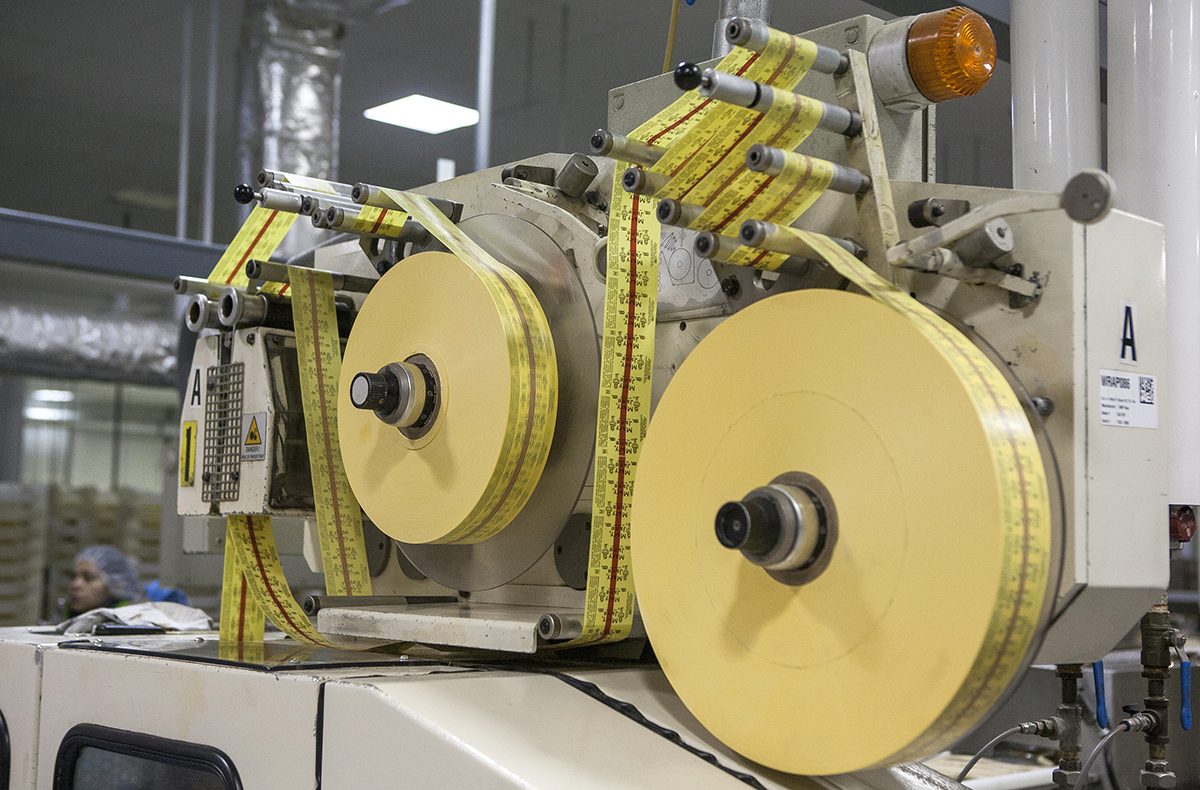

Exploring Necco’s 800,000-square-foot plant in Revere, which they moved into after 76 years at 254 Mass Ave. in Cambridge, you no longer see a line of open-fired kettles for the production of freshly made fudge or employees, gloves up to their elbows, dipping handfuls of raisins into tubs of chocolate to make raisin clusters. But there still is a hands-on element that has been abandoned in most confectionary companies this size.

There’s a designated Taffy-Pulling Room for the assembly of Squirrel Nut Zippers; a Panning Room where employees coat peanuts and malt balls in milk chocolate using giant, revolving cement mixers that are older than Fenway Park; and a peanut roastery for the construction of house-made peanut butter, which is then chopped, massaged, and squeezed into the center of every Mary Jane.

Malt balls being coated with chocolate in the Panning Room. Photo by Olga Khvan

While walking through one nondescript corridor, several employees pass by, their white shoes now dyed pink from a morning handling the dough for wintergreen Necco Wafers. Mary Lane, a member of Necco’s marketing and social media team, stops short and pulls a string hanging 30-feet from its vaulted ceiling. A wall slides open to reveal a shadowy boiler room where the temperature inside is a muggy 90-degrees and everyone is wearing respirators to combat the ground cocoa dust that hangs heavy in the air.

Unlike their competitors, which outsource the production of chocolate (not to mention almost every other ingredient), Necco continues to make every component necessary for their line of confections. Not only is that a source of pride, but it’s the primary reason Necco hasn’t up and followed Hershey’s to Monterrey, Mexico, or the cornfields of the Midwest. Many of the guys who passed by that morning with pink shoes—and all the women stacking Necco Wafers in metal molds, tweezers in-hand, ready to pluck out any chipped or cracked discs—they’ve been there for decades. Out of Necco’s 300 employees (500 during the holiday season), it’s not uncommon to speak with people who have been there for 40 years. Their intimate knowledge of every Clark Bar, Mighty Malt, and chocolate covered raisin would be almost impossible to duplicate outside of Massachusetts.

“This is now a one of a kind facility. They don’t exist anymore,” says McGee. “I think to justify it and be competitive here, it comes down to our ability to be resourceful. So yes, there is some high costs in this area, but there’s access to employees with years of experience. The heritage of being from here is something we’re proud of. Our customers and suppliers root for us. They like the fact that all of our candy is made here in America, and that’s something we leverage.”

While Green was part of the team that famously offended generations of Necco Wafer loyalists with his decision to substitute artificial dyes and flavors with natural colorings made from turmeric, red beets, purple cabbage, and cocoa powder in 2010 (Green blames the muted color palette for the public’s outrage), he and the top brass have learned much from the healthier, organic-obsessed Millennials they were trying to reach.

Mary Janes

“We employ union employees, and utilize U.S. sugar and ingredients. We make everything here in Boston,” McGee says. “That certainly is a big selling point for our customers, including big players like Walmart, Costco, and CVS who are making that a priority. You see a lot of retailers now moving toward regionalizing their offerings to take advantage of these localized things. We can deliver against that.”

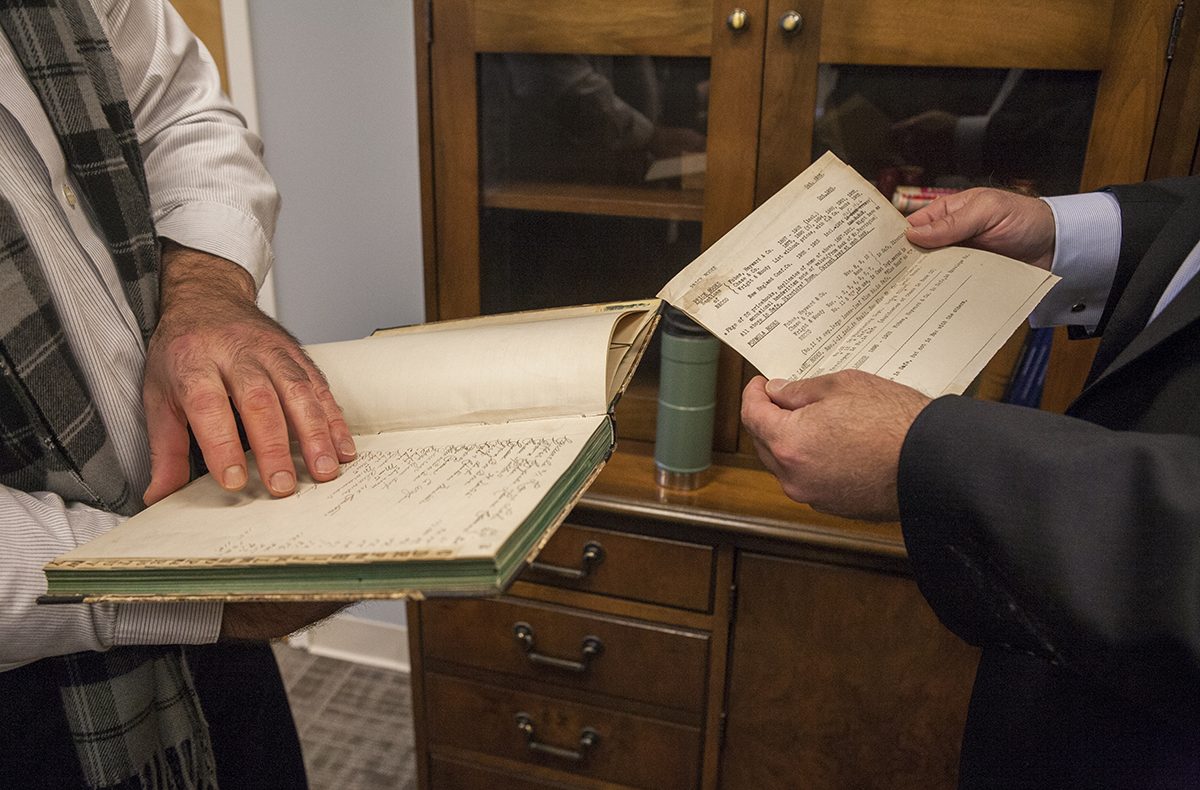

Green, who is a walking encyclopedia of candy knowledge, has an office lined with both competitors products as well as historic Necco artifacts, all of which he dug out of the trash during the 2003 move—single-handedly salvaging much of the company’s history. He studies everything from handwritten recipes from Necco’s late-19th century ownership group, Fobes, Hayward, and Company, to the current artisanal bean-to-bar movement, looking for the trends that will stick, as well as the ones that will plummet the company back into the red.

Necco has finally recovered from their “all-natural” debacle of 2010, and actually grew their business seven-percent in 2014. This year, the company made over two billion Sweethearts, or the equivalent of 30 million one-ounce Valentine’s boxes. They utilized 20 million pounds of sugar and grew Sky Bar’s presence in its native New England. Even McDonald’s has recognized the cultural significance of Necco’s most famous treat. This February you’ll be able to find stuffed conversation hearts, with messages like “BFF” and “Dream Big,” in every Happy Meal.

“Coming over to Necco has been this tremendous opportunity,” says McGee, who was formerly with Mars in New Jersey. “It was a candy that I knew from growing up. There’s great bones and structure here. It’s a great facility with an unparalleled heritage. The candy industry is a $27 billion dollar a year business, so there’s lots of room for competitors. But that being said, we offer products that are so distinctive and unique, we don’t have a lot of direct competition. We’re almost a category unto ourselves.”

Necco Wafers