Respecting the Craft: An Oral History of Cambridge Brewing Company

As the Kendall Square brewpub celebrates its 30th anniversary, we went straight to the source to learn how this neighborhood restaurant fermented Boston's now-booming craft beer scene.

In many ways, this past Saturday was a normal day at Cambridge Brewing Company. Brewmaster Will Meyers and founder Phil Bannatyne mingled with longtime regulars seated at the bar and crowding the patio. Chef David Drew and his team manned the grill outside—a regular happening at CBC’s frequent festivals—and inside, cranked out orders of buffalo chicken tenders, nachos, and more locavore pub grub.

And of course, the draft lines flowed with beer. This cloudy May day even featured Benevolence: a strong, bourbon barrel-aged dark sour ale that was one of the first American experiments in both barrel-aging beers and blending sour ales when it arrived on the scene two decades ago.

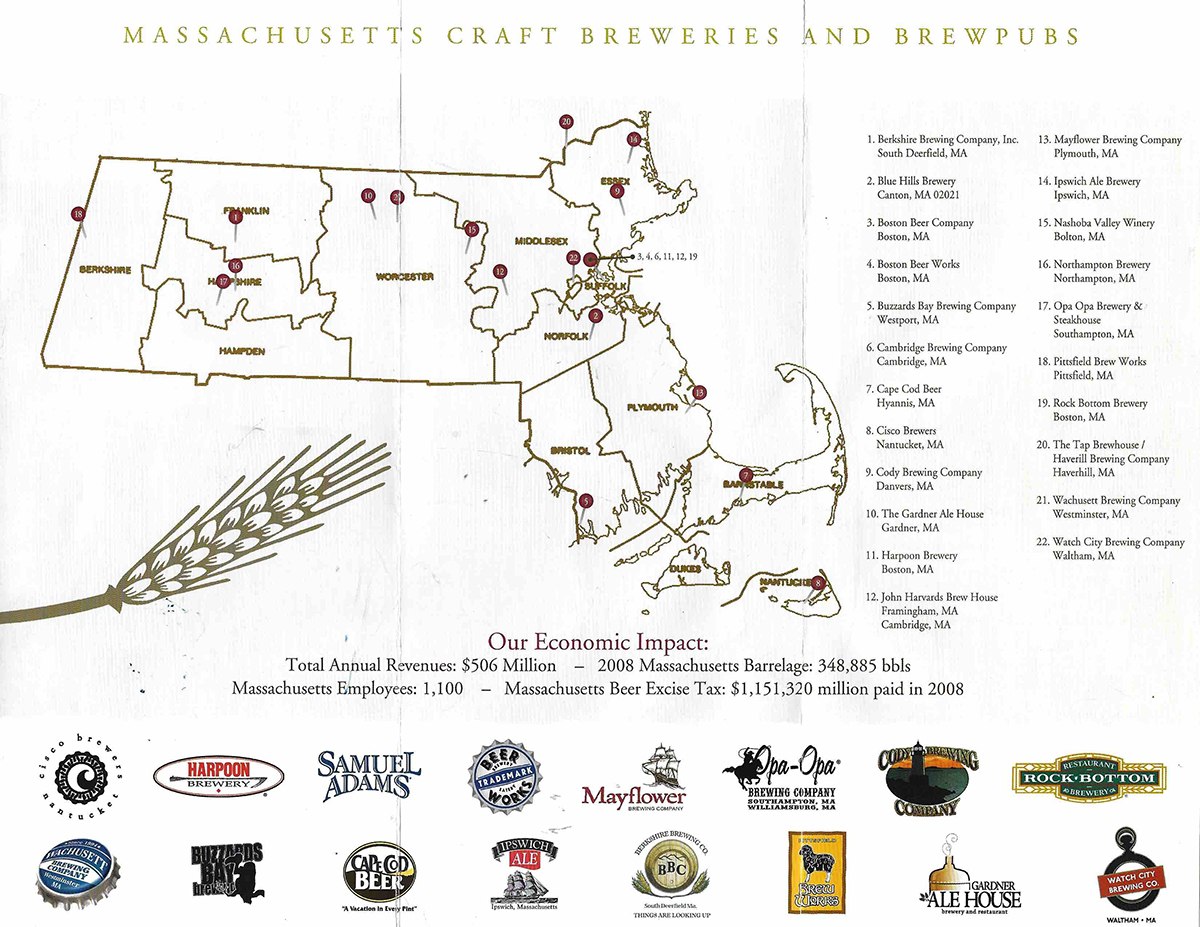

That’s because there was a special reason for celebration. It was the influential brewpub’s 30th anniversary party, and the guests included many CBC brewing alumni who came to toast the stalwart spot’s history. (Many also teamed up the day before to brew a special, new beer together—stay tuned for that release.) They represented a who’s-who of current brew-world notables, including Ben Roesch, cofounder and brewmaster at Wormtown Brewery; Megan Parisi, the current research and development brewer at Samuel Adams’ Boston production; and Ben Howe, the one-time Enlightenment Ales sage who just announced plans to open his own brewery in Washington State.

Cambridge Brewing Co.’s family tree has branched to every corner of the industry. Other CBC vets include the founding taproom manager at Worcester’s new Redemption Rock; the owners and brewers of Honest Weight Artisan Ales in Orange, Mass.; and the chef and brewer of the soon-to-open Brato Brewhouse + Kitchen in Brighton. The CBC reach extends across the country, with alums now making beer in Austin, Texas; Wells, Maine; Richmond, Virginia; Sonoma County; and elsewhere. The storied team has also spawned a drinks writer, a brewery consultant working in Asia—the list goes on.

Few other operations could claim to be as impactful on our region’s craft beer landscape. What has allowed this neighborhood restaurant to make such an impact on the craft brewing scene in Boston and beyond? We tapped the original team–and those who mashed in, sampled barrels, and shared pints along the way. Here’s the story of CBC, in their words.

These interviews have been edited for clarity.

Brewing an Idea

When Phil Bannatyne was preparing to launch Cambridge Brewing Company in then-sleepy Kendall Square, the modern craft-beer revolution had only just begun. A Bay Area resident in the 1980s, Bannatyne found inspiration in other beer pioneers—like Reid Martin, whose 1986-founded Triple Rock is a trailblazing brewpub in downtown Berkeley, California—but this was mostly uncharted territory.

Phil Bannatyne (CBC founder): I remember the infancy of the new craft beer movement, but I was doing something completely different. I owned a balloon company. We delivered bouquets of balloons, and decorated weddings and campaign events, things like that. I was in a homebrewing club named the San Andreas Malts. I only ever waited tables in college. In the mid-80s, I took a couple courses in Brewing Science at the UC Davis Extension School. The whole point was to get as much brewing knowledge in a short of amount of time so I could get the basics and pursue opening a brewery. A person of note in my class was a guy named Reid Martin. I looked at what Reid did and I said, where’s a progressive college town where I can do that? I’m originally from Connecticut and I wanted to come back to the East Coast. Kendall had a few tall buildings, and the infancy of biotech was here. But at night, there was pretty much nothing. I was told not to come here by my restaurant consultant.

Will Meyers (CBC brewmaster and partner): There were loads of empty lots still when I started coming here in the early 1990s. I started homebrewing in 1990, and I think I just annoyed Phil until he offered me a job. I still annoy him.

PB: And I haven’t taken the job away.

WM: I would drive around New England and show up super early in the morning at different breweries, like Catamount in Vermont, Commonwealth downtown, Northampton Brewing Co., Ipswich, and Harpoon across the river. I would hang out and offer to clean kegs if they’d teach me how to mash in and mash out.

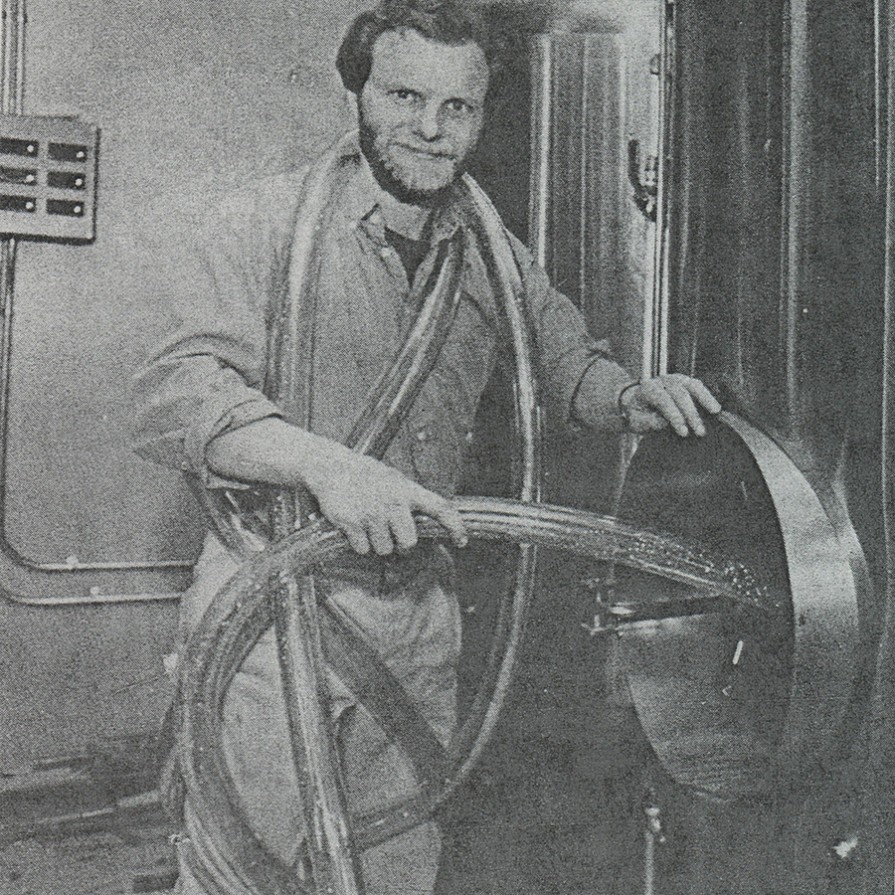

Will Meyers and one of his mentors, brewer Tod Mott, at the Great American Beer Festival in 2008. / Photos courtesy of Cambridge Brewing Co.

Tod Mott (cofounder and brewer of Tributary Brewing; Harpoon brewer 1991-93, creator of Harpoon IPA): Will studied with me for a little while. He kept bringing me home brews, like, “Hey, will you try this?”

WM: I would insist he tear it apart and be as constructively critical as possible. To his credit, Tod was very interested in helping me make better beer.

TM: Will was innovative from day one, and that was kind of cool. I think he actually made one of the first sour beers I ever tasted. That was a long time ago. He was young, but he knew what he wanted to do. I put him to work.

WM: I traded education for free labor for a few years. My first day at CBC was April Fool’s Day, 1993.

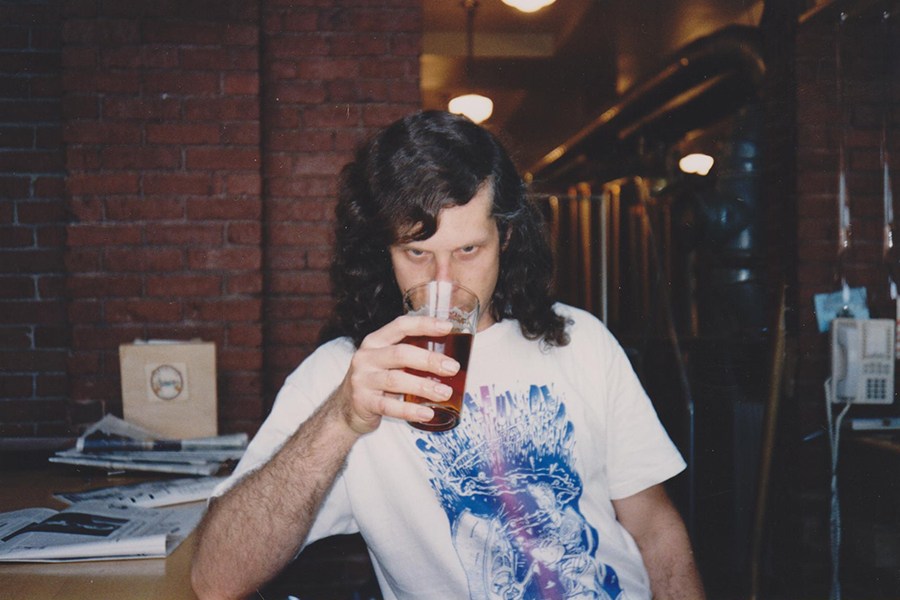

PB: We opened in May of ’89, and at first I made the beer. It was probably the beginning of 1990 when Darryl Goss, then a homebrewer of some renown, put his hand gently on my shoulder and said something to the effect of, “Phil, you could use my help.” Frankly, I could. The beer was not all that good.

Crafting an Identity

Cambridge Brewing Company actually opened in early April 1989—but without any beer, thanks to an equipment snafu. Despite that inauspicious beginning, the tiny brewpub quickly became a beer industry leader. After lead brewer Darryl Goss joined the team in 1990, he developed the first Belgian-style beer brewed in North America: Tripel Threat, which also became the first Belgian-style beer to win a medal at the Great American Beer Fest. As a neighborhood restaurant, CBC was quick to recognize the value in pairing locally made brews with quality, locally sourced food. One important lesson that was (quickly) learned: Always keep buffalo tenders on the menu.

Original CBC brewmaster Darryl Goss sips the fruits of his labor, circa early-1990s. / Photos courtesy of Cambridge Brewing Co.

Phil Bannatyne: It was early on that I realized the food component needed to play a larger role. If I’m comparing it to the Triple Rock model, with just simple soups and sandwiches–Berkeley kids drink. I put my brewpub next to MIT; those kids study.

Will Meyers: Phil was already thinking about “local beer,” and he liked the idea of the beer reflecting local food, so we started looking for local sources pretty early in the game.

PB: It’s been exciting, and it’s a whole other part of our creativity: sourcing local ingredients and designing food and menus that go with the beer.

WM: Now we have local malts, Massachusetts and New England-grown hops, and all kinds of cool herbs and fruits and orchards that are being reinvigorated by the craft beer and cider industries here.

David Drew (CBC executive chef since 2008): I used to work the line at Harvest with Keith Pooler [now chef-owner of Bergamot and Bisq] and one of our shift drinks was CBC Amber. I love beer, so I knew them. I remember, in my job interview, in a self-deprecating way, Phil asked why I was going from a fine-dining environment to a brewery. But we were on the same page about trying to do the right thing sustainably. How come breweries don’t get to work with local farms and be progressive? But I didn’t reinvent the whole wheel. It’s always had a local vibe. And you can’t get too pretentious. We’ve had buffalo tenders on the menu forever. CBC was my first head-cheffing job; I guess I was showing off when I took them off the menu. I got pushback from everybody. People boycotted the restaurant. We put them back on the menu, and we held an event, emceed by Phil, with an eating contest. That was my first lesson right off the bat: I’m not bigger than CBC.

As CBC’s popularity grew, other restaurants took notice—and reached out to tap into their success.

Herbert Kuelzer (founder of Grendel’s Den in Harvard Square, 1971): I was very taken by the idea of a Cambridge brewing company.

Cambridge Brewing Co. beers are still a top seller at Grendel’s Den in Harvard Square. / Photo courtesy of Grendel’s Den

Kari Kuelzer (second-generation owner of Grendel’s Den): We couldn’t serve alcohol at Grendel’s for like, 12 years. [Grendel’s Den won a landmark Supreme Court case in 1982 establishing the separation of church and state in Massachusetts, after suing a church that blocked the restaurant’s liquor license application.] In that context, I can imagine my dad found it very hard to believe that there was all of a sudden a brewery down the street.

PB: In 1990, I got a call from Herb Kuelzer, who said, “I heard you’re making beer here in Cambridge. I would serve it if you put it in a keg and bring it to me.” I said, “Herb, that would be great, I’d love to do that,” and I hung up the phone and then I said, OK, I don’t own any kegs, and I don’t really know how to clean or fill them.

WM: When I started here, it was to wash kegs and make deliveries in our piece-of-crap van. But pretty soon I got my hands in making every single batch of beer, with either Phil or Darryl in the brewhouse with me. I got to pretty much learn how to run the show very quickly.

PB: Grendel’s was our first account, and we’ve been on there ever since.

KK: The first beer I drank when I turned 21 was a Cambridge Amber at Grendel’s bar on May 28, 1991.

HK: It turned into a tremendous seller. I sold more Cambridge Brewing Co. beer than all the drafts together for the first few months. It was the cat’s meow.

KK: It’s one of our most popular products, hands down. We carry Cambridge Amber, and a rotating sour.

The Pint Runneth Over

Darryl Goss left CBC in 1997, and died from ALS in 2012. But the CBC team has continued his legacy of experimentation, rooted in respect for brewing history. Since 1990, CBC has earned more than 15 medals from the Great American Beer Festival, the World Beer Cup, and other industry honors. With Bannatyne’s blessing, Meyers established—in CBC’s minuscule, dank cellar—one of the first barrel-aged beer programs in the United States, contemporaneously with much larger breweries like Samuel Adams and Goose Island in Chicago.

A barrel-fermented wild ale with cherries, Cerise Cassée is made with an innovative fermentation system called solera, or “fractional blending.” It’s been released annually since 2003, and every batch contains a fraction of each earlier vintage. / Photos courtesy of Cambridge Brewing Co.

Phil Bannatyne: Now, a third of the beer we make here, we distribute to other bars and restaurants in Cambridge and Somerville. We produce about 1,500 barrels here annually, and in total, about 3,500. This is still our original, 10-barrel system in Cambridge, but we’ve added fermentation capacity. We have sort of a ladder here, when you start as keg washer and delivery guy, you move up to assistant brewer, then to head brewer–and then a lot of them move on.

Will Meyers: Phil and I had a great meeting at an annual review many years ago, and we became partners. I love it here, and I love not having to justify what I want to do. I’ve been the one to come to Phil with an idea, and he kind of puts his head in his hands, and says, “What is it now?” And then we do it, and it’s awesome, and it starts a trend of 1,000 other breweries making barrel-aged sours.

Megan Parisi (research and development brewer at Boston Beer Co., makers of Sam Adams; CBC brewer 2004-2011): I started working here in the 15th anniversary year. One of the early projects was Cerise Casée, the sour mash and solera-barrel system, which was pretty darn innovative. Barrel aging beers was really something I didn’t have any experience with as a homebrewer. It was a very small and still-growing aspect of the craft beer industry. Sam Adams, where I work now, was one of the other early adopters of a barrel-aging program with their Triple Bock, Millennium, and Utopias. Especially for a little brewpub to have a major barrel-aging program—it couldn’t have been a setup that made sense. But that didn’t stop Will. That’s maybe a creed or something he’s figured out: Just because it’s not easy doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing.

From 2008: Will Meyers, CBC brewer Ben Howe (Enlightenment Ales, Other Wonders Beer), national Brewers Association and Great American Beer Festival founder Charlie Papazian, CBC brewer Kevin O’Leary (Ardent Craft Ales), CBC brewer Megan Parisi (R&D brewer Sam Adams). / Photos courtesy of Cambridge Brewing Co.

Besides the drafts and bottles sold at the Kendall Square brewpub, CBC also works with a distributor to get its kegs and cans placed throughout the state. To meet growing demand, the team worked out an arrangement with Chelsea-based Mystic Brewery, one that helped both operations take themselves to the next level.

PB: We always did growler fills, but people had been asking us for packaged beer for years. In 2011, around the 22-ounce bottle craze, Will and I basically looked at each other and said, “oh, what the hell?”

WM: From the start, I wanted to have our bottled beers be an extension of our barreled beer program. Five years ago I had the opportunity to buy a 20-barrel brewhouse from my friend Shaun Hill, who has a brewery in Vermont called Hill Farmstead. I came home to Phil and said, “Shit, I just bought another [brewing system], and I don’t know what I’m going to do with it.” We talked about it, and realized we didn’t really want to open up another production brewery to run, and staff, and manage full-time. We also realized we were in a position to be a little philanthropic because we had the equipment.

Bryan Greenhagen (founder of Mystic Brewery): We were looking for a brewhouse at the time, but Will came to us with the idea to sell us the system, without any interest, if they could take a corner of the brewery to do their bottling program, ’cause we had a cork-and-cage bottling machine and a bunch of room.

WM: We looked at some of the other newer breweries around, and realized some of those brewers could really use a leg up to make that next leap in scale that they probably can’t afford at that time.

BG: We never had the intention of being a contract brewery. The only reason we did it, besides that they got us a great brewing system on easy money, is we thought it would be amazing to help them get that barrel program out from under the cellar. Among brewers, that’s a legendary basement. Everybody’s got a barrel program, but 28 years ago they did not. We thought it would be great if Will could put Cerise Cassée in bottles and people would actually be able to get it, instead of only being able to get it at the brewpub. We’ve paid off the brewhouse, but we’re extending CBC’s contract right now. They have someone, Lee Lord, who works here full time. It’s super collaborative, and it’s been super smooth. They’re really part of the family.

Lead CBC production brewer Lee Lord draws a barrel sample at Mystic. / Photos courtesy of Cambridge Brewing Co.

BG: Ultimately, you know what’s amazing about those guys? That Phil let Will have that latitude to explore things Americans knew pretty much nothing about. It was forward-thinking and yielded a lot of knowledge.

Building a Legacy

The influence of CBC has been felt far and wide over the years. That’s thanks to its team’s mentorship of the next generation of craft beer players, and its own ongoing commitment to balancing tradition and innovation.

Megan Parisi: One of my favorite things about CBC is that so many people start their brewing careers there, like I did, and make that transition from amateur to professional. For example, Ben Howe and Sean Nolan [founders of Other Wonders, and Honest Weight Artisan Beer, respectively] both worked for me [at CBC], but they never overlapped there. They wound up working together later, over at Idle Hands. Ben told me that he and Sean immediately knew they could trust each other because they both learned from me. That was probably the proudest I’ve ever felt. After CBC, I went onto Wormtown. Ben Roesch hired me. Again, we never worked together at CBC, but we were acquainted with each other for a decade, and he knew what I could do.

Phil Bannatyne: That’s a big part of what Will does, he’s constantly mentoring his staff.

Will Meyers crouches in the barrel cellar at CBC, circa 2006, to add fruit to an aging beer. / Photos courtesy of Cambridge Brewing Co.

Will Meyers: I believe brewing encompasses artistic creativity, but also has a strong basis in process. It’s a craft, and crafts deserve respect. I think the apprenticeship and mentor model is going to produce the best brewers and make beer of higher and higher quality as our industry continues to grow.

PB: Will has this thing about preserving historical styles.

Jay Sullivan (owner and brewer at Honest Weight Artisan Beer; CBC brewer 2010-2015): I pushed really hard for the first grisette [a light, saison-like beer] to be brewed at CBC, and a couple years later we barrel-aged it and it won a medal. We brew a lot of grisettes at Honest Weight, and they’re still inspiring to me.

PB: He’s also trying to make beer better in the U.S., and he’s been recognized for it.

Paul Gatza (senior vice president of Professional Brewing Division, National Brewers Association): In 2017, the Brewers Association presented Will Meyers with the Russell Schehrer Award for Innovation in Craft Brewing. The annual award is voted on by past winners. The three key features in what puts a person over the top are: excellence in craft brewing, innovation that moves craft brewing in new and interesting directions, and a willingness to share/mentor in the craft brewing community. Will has certainly done all of these things. He is dedicated to quality and consistency, but at the same time wild experimentation–which both leads and follows our collective efforts as an industry of craft brewers.

CBC brewers’ Christmas card 2011, (L to R) Sean Nolan (Honest Weight), Adrian Beck-Oliver (Hidden Cove Brewing), Jay Sullivan (Honest Weight), Phil Bannatyne, Will Meyers. / Photos courtesy of Cambridge Brewing Co.

WM: I love hoppy pale ales and IPAs. I don’t think the haze craze is a phase–and I didn’t intend to rhyme, either. But the popularity of IPAs dominating over everything else does cause me concern. Which is why, over the last few years, we’ve put even more effort into making sure when we do a lager, it’s awesome. When we do an unhopped herbal beer, it’s really cool and delicious. When people do step out of their comfort zone, it’s that much more important that the experience for them is awesome, or else they’re not going to open up their view of what beer can be.

Click to view larger. / 2009 map courtesy of the Massachusetts Brewers Guild

PB: Restaurant margins are notoriously thin, but when you manufacture and sell your own beer at full pours to the public, that cushions things a little bit. And a large part of our appeal is that we have always pushed boundaries. People come and seek that out. But is it harder now? It absolutely is. There are so many new restaurants, and they’re all really good. The kids with their apps have to go and check off the new beer, and most of the beer is really good. The new breweries get the hype.

WM: It’s also important to keep our prices reasonable, to make sure people can try things. When I started working with Darryl and Phil, we didn’t start making saisons or whatever because we wanted to be the first to do them. We did them because we had read about them, or tasted them, and thought it would be cool to try to make back at our place. I made a Norwegian rye malt sahti with juniper berries back in 1993. Nobody wanted to drink that beer. I remember we did a smoked rye beer around the same time that was an equally hard sell. Nowadays, we make a smoked beer with our neighbors at the Smoke Shop, and it flies. It’s amazing how just a couple of decades of education and familiarity has opened up people’s willingness to try new things.

Jon Gilman (cofounder of Brighton’s forthcoming Brato Brewhouse + Kitchen; CBC cook and sous chef 2008-2017): I was at CBC for six years total, and in the last four years my bosses knew I was writing a business plan. There was never any hesitation or pushback; it was always encouragement. We definitely wouldn’t have been able to do it without the help of Phil, and the guidance of Will, and Dave in the kitchen. You couldn’t have a better system for support. We’ve seen it out there in the beer industry: It seems like Phil has set the standard to all work towards a single goal of furthering craft beer.

WM: We’ve got a dozen or so Great American Beer Fest medals and a bunch of World Beer Cup awards, and certainly the Schehrer award was a complete honor. But I also love the fact that nobody in Cambridge gives a shit about that, because it means I can quietly do my thing. That’s one of the things I love best about CBC. We have regulars who were literally here the day we opened, but there’s always new people discovering us, even though we’ve been here for 30 years. That’s a testament to Phil and the place he wanted to create. One of the things that’s so special about Cambridge Brewing Company, there could be a house-painter sitting next to an astrophysicist sitting next to an artist sitting next to someone else. There’s all walks of life, and they tend to talk to one another. It’s important that we have beers that are conducive to conversation.