An Insider’s Guide to the MFA’s Monet Exhibit

Don't miss these tips from a Museum of Fine Arts curator on how to get the most out of "Monet and Boston."

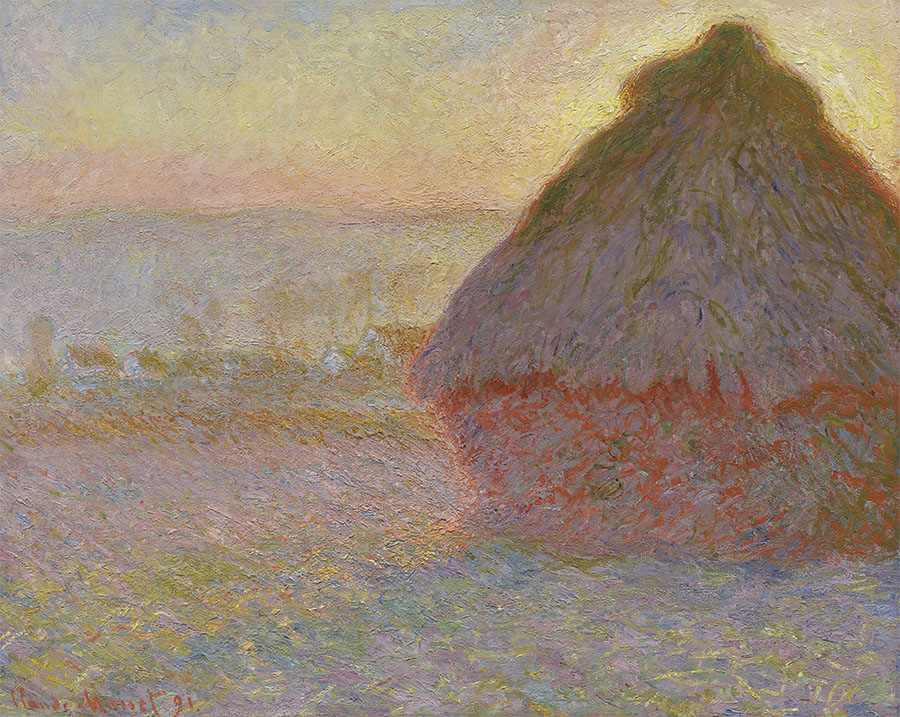

Grainstack (Sunset)

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926)

1891

Oil on canvas

* Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection

* Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Like any good sequel, the Museum of Fine Art’s second “Monet and Boston” exhibit in as many years retains some themes from the previous show of impressionist master Claude Monet’s work, while providing museum-goers new works and pairings to admire.

“Monet and Boston: Legacy Illuminated” follows 2020’s pandemic-curtailed “Monet and Boston: Lasting Impression,” which had been launched in honor of the museum’s 150th anniversary. The current exhibition opened to the public on April 17, and will run through the summer until October. And while the diminished capacity from lockdown meant the exhibit space had been selling out, the lifting of all pandemic restrictions means there’s never been a better time to check it out.

Visitors can also expect to see work from Monet’s predecessors and inspirations, including Eugène Boudin and Jean-François Millet, as well as sculptures by contemporary and friend Auguste Rodin. But there’s quite a lot to take in from the multi-room exhibit. Read on for a room by room guide from Katie Hanson, curator of paintings, art of Europe, and Marietta Cambareri, senior curator of European sculpture, and learn how to get the most out of the MFA’s big exhibit.

Becoming Monet

First things first: Don’t just breeze past the black and white film of Monet at the entrance of the exhibit. Wait for the dramatic pause at the end of the film for a dramatic reveal of the first room of the gallery through a translucent scrim.

In the first room, visitors will find themselves admiring Entrance to the Village of Vétheuil, Winter–maybe even remarking that the patchy snow-covered ground looks an awful lot like early and late Boston winters. But as a Monet expert, you’ll notice the taupe coloring in that section, which isn’t paint at all, but canvas the artist intentionally left exposed.

Along that same left wall, don’t miss two paintings placed next to each other, on the corner. Facing Late Afternoon, Vétheuil, the painting The Seine at Lavacourt is at your back. These impressions are placed in these positions quite intentionally, because as Monet was painting Late Afternoon, the landscape depicted in The Seine would have been to his rear.

“This was an opportunity that was really amazing to think about how much visual variety he found in the world around him,” says Hanson.

Monet and Japonisme

Japonisme is a French term that describes Japanese art’s popularity among Western artists in the late 19th century, and the room seeks to display how Japanese art influenced Monet.

The primary fixture in the room is the life-size, vertical painting of a woman in a red kimono holding a paper fan: La Japonaise.

This painting holds clues that contradict how people usually conceive of impressionist painting, says Hanson. While many of Monet’s paintings look like fast sketches, using the light, you can see areas in La Japonaise where Monet went back and made corrections. Bend down to the right, and the light reveals a “halo” around the paper fan, suggesting the painter adjusted its placement.

“We often think about Monet as someone who painted quickly,” says Hanson. “That’s not always the case, especially in a giant figure painting like this one.”

One thing to keep in mind throughout the exhibit is that Monet and Boston is also an appreciation of how fervently Bostonians collected Monet’s art, even in his lifetime. This is partially, Hanson said, because Bostonians already had a strong appreciation for the Japanese woodblock prints from which Monet drew inspiration. You’ll see some of these woodblock prints placed around La Japonaise, including one just to the right of his painting that also depicts a woman with a fan, titled Grape Arbor.

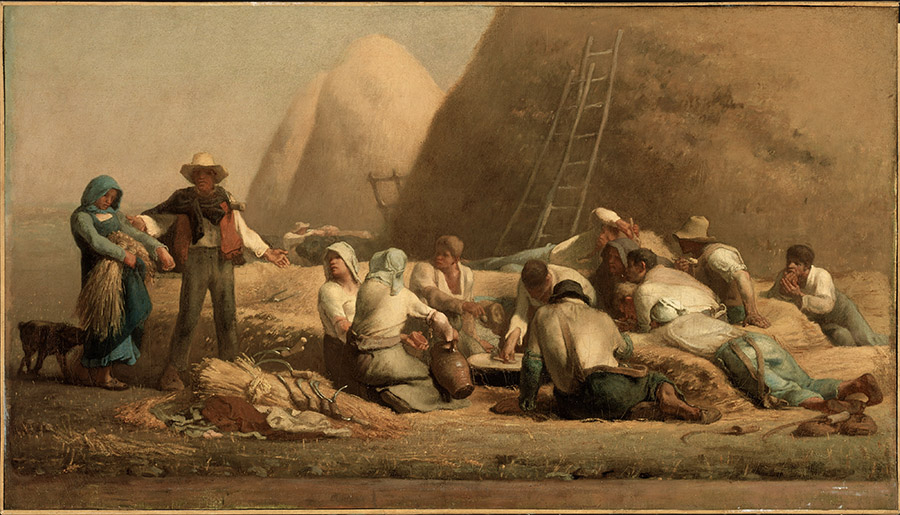

Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz)

Jean-François Millet (French, 1814–1875)

1850–53

Oil on canvas

*

Bequest of Mrs. Martin Brimmer

* Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Monet and Millet

After Monet and Japonisme, the next room is dedicated to Monet and Jean-François Millet, a French avant-garde painter who paved the way for impressionism and was collected by Bostonians in “even greater depth and intensity” than Monet, says Hanson.

Hanson particularly highlighted a Millet called Cliff’s at Gruchy, a work often mistaken for a Monet thanks to the dazzling quality of the light and the way Millet laid out all the elements in the cliffside scene. The foreground dominates this painting, in much the same way you might have spotted in Monet’s works, though you’ll want to be sure to let your eye wander to the background to appreciate a few seagulls and a small boat in the water in this work. One very notable way to spot that it’s not a Monet, of course, is that Millet doesn’t use the quick, bold brush strokes associated with impressionism.

Further into the room, the curators reveal the thoughtful deliberation behind the layout of the exhibit. To the immediate right of the entrance to the next room—Monet, Rodin, and Boston—is Harvesters Resting, a painting by Millet.

The subject of the painting is, well, harvester’s resting. Behind the laborers, however, are large mounds that will look awfully familiar to the devoted Monet fan. They’re haystacks. And if you position yourself right and peer through the doorway into the next gallery, you’ll see from Harvester’s Resting through to Monet’s Grainstacks, a landscape of haystacks.

“So, you’re seeing grain stacks in Millet, and then looking into the next gallery and seeing that subject that we all so closely associated with Monet,” says Hanson.

Ceres

Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917)

1896

Stone; Marble

* Anonymous gift

* Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Monet, Rodin, and Boston

Immediately to the right in the Monet, Rodin, and Boston room is another black and white film, this time of Rodin. Watch him work and sculpt but stay until the end: Eventually, Rodin turns to the camera displaying his face and big beard, which is filled with chunks of stone.

What’s notable about Rodin’s sculptures, says Cambareri, are their unfinished nature. This allowed admirers to observe the actual strokes the sculptor used to craft his works. In the sculpture Ceres, for example, there is a visible claw chisel mark on the chest of the deity (In the exhibit, Ceres, the goddess of grains and cereals, is also intentionally placed next to Grainstacks).

Placed in the center of the room, with ample space to circle the sculpture, is one of Rodin’s most famous pieces: Eternal Springtime. They put the sculpture in the center of the room so visitors can find otherwise concealed details.

Below the nude male figure, sculpted into the base in the back, is a distressed face, pointing up. Probably the Head of Sorrow, says Cambareri, a motif reused by Rodin and “a little footnote on how he actually works.”

Another detail hidden in the back of the sculpture is the signature. It’s special, dedicated to a young female relative of Rodin’s. “It’s dedicated to his [cousin] who took care of him when he was a sick old man,” says Cambareri.

So what are you waiting for? Get out there and wow your friends with your expert impressionist knowledge.

$32, through Oct. 17, Museum of Fine Arts, 465 Huntington Ave., mfa.org