Researchers Working on a Urine Test for Breast Cancer

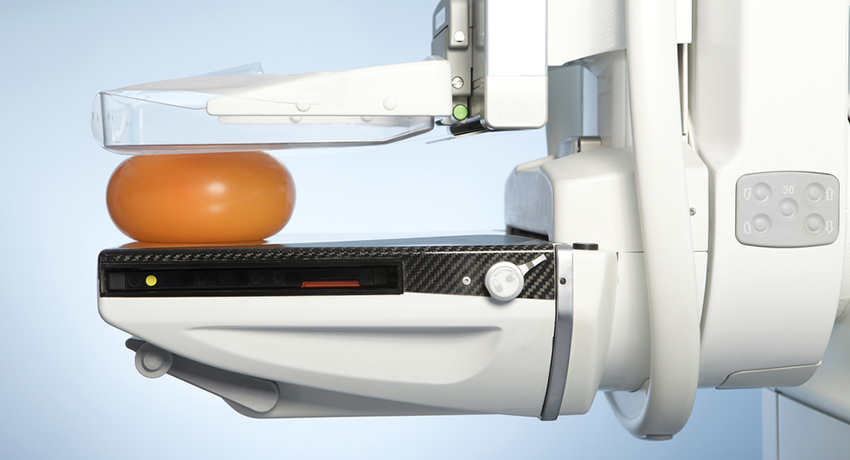

Mammography machine photo via Shutterstock

A mammogram is an x-ray picture of the breast. But that much you know already. If you’ve never had a mammogram, what you may not know is that it usually hurts, not in a sharp pain kind of way, but in an unpleasant, OMG when is this going to be over, kind of way. After all, your breast is mashed between two heavy objects (see above) to get the image. And because of this pain, many women put the procedure off, even though women over 40 should have the procedure done as part of their regular checkups—and even though it may save lives.

So when we see a headline that says, “Could This Be The End of the Mammogram?” from a well-respected publication like Prevention, the go-to destination for health and wellness news, we get excited. It’s only until we read further into the story that we realize we got bamboozled by a headline.

Prevention is reporting that researchers at Missouri University of Science and Technology developed a new screening method that uses urinalysis to diagnose breast cancer and its severity before it can be detected with a mammogram. Clinical trails are happening now.

Prevention reports on the study and quotes researcher Casey Burton:

Once they reach their goal of 500 testing samples, if this theory pans out, it could change breast cancer screening as we know it, and, ultimately, revolutionize testing for other cancers as well.

“This would be a 10-minute test where urine is collected during your annual physical and by the end of the check-up you’ll know the result,” says Burton. “Mammograms would then be used for follow up imaging, but would no longer be necessary for routine screening.”

The method the researchers are developing uses a device called a P-scan to detect the concentration of metabolites called pteredines in urine samples. Pteredines are present in the urine of all humans, but abnormally high concentrations can signal the presence of cancer. Ma [the developer of the test] also believes the levels continue to rise as the cancer advances.

This seemed too good to be true, so we asked Dr. Mehra Golshan, director of breast surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, for some answers. And we were right.

Could a urine test actually replace a mammogram?

“I can’t imagine it actually replacing a mammogram,” Golshan says. “Mammography is something that has been around for decades and there have been a lot of improvements done, and mammograms can find abnormalities that lead to biopsies. I just don’t see [the urine test] happening anytime in the near future, and when I say the near future, at least a decade or so. And even then, I still think it’s farther along than that. There’s been work being done on trying to find breast cancer besides mammogram with all types of other types of pictures of the breast: MRI, tomosynthesis, elastography, thermography, and molecular breast imaging.”

There have been studies on pteredines before and so far there is no proof that they’re the marker for breast cancer, is that correct?

“There have been groups that have looked at this before,” Golshan says. “If you go back to 2004, there was a group here in Boston that looked at a urine test for breast cancer, and they did a lot of research published on it and didn’t find anything. It wasn’t the marker that was the magic bullet.”

So you are saying that high levels of pteredines may not signal breast cancer?

“Exactly. And then why would it just be specific for breast cancer and not other types of tumors? I could see that if you make something simpler and say it works just as well as something like a mammogram, which most women don’t look forward to. Having then, just like a lot of the things, [like] with Angelina Jolie and the gene mutation, and she removed both her breasts and now we’re getting calls that, ‘I should remove both my breasts,'” Golshan says. “Is it good and exciting to look at something that is minimally invasive such as peeing in a cup or on a dipstick or whatever they end up trying to look at and then telling you that, like a pregnancy test, yes it’s positive or negative? But we know [mammography] works.”

Is there a common marker for breast cancer?

“No. There are things that they’re more common in certain types of breast cancer, for example, like estrogen receptors or HER2 receptors, there’s the genetic component where about 7 percent of cancers in the U.S. are hereditary but 92 percent aren’t,” Golshan says. “So there are certain things that can be more common versus less common, but there’s really nothing that all breast cancers have X or Y or Z. We actually found out that it’s a very heterogenous disease… a lot of differences between cancer from woman to woman. Now what we’re often doing is actually tailoring their treatment and therapy to their specific cancer as opposed to general breast cancer.”

Is this report on the urine test really just to grab headlines?

“Yes, it’s something to further research and look forward to how far off, decade plus at the earliest, and it would never replace mammogram. See it as maybe an adjunct or additional test,” Golsham says. “It’s catchy and it’s breast cancer, which always gets a lot of publicity, so I can see how this is attention-grabbing.”