Luciano Manganella’s Final Sale

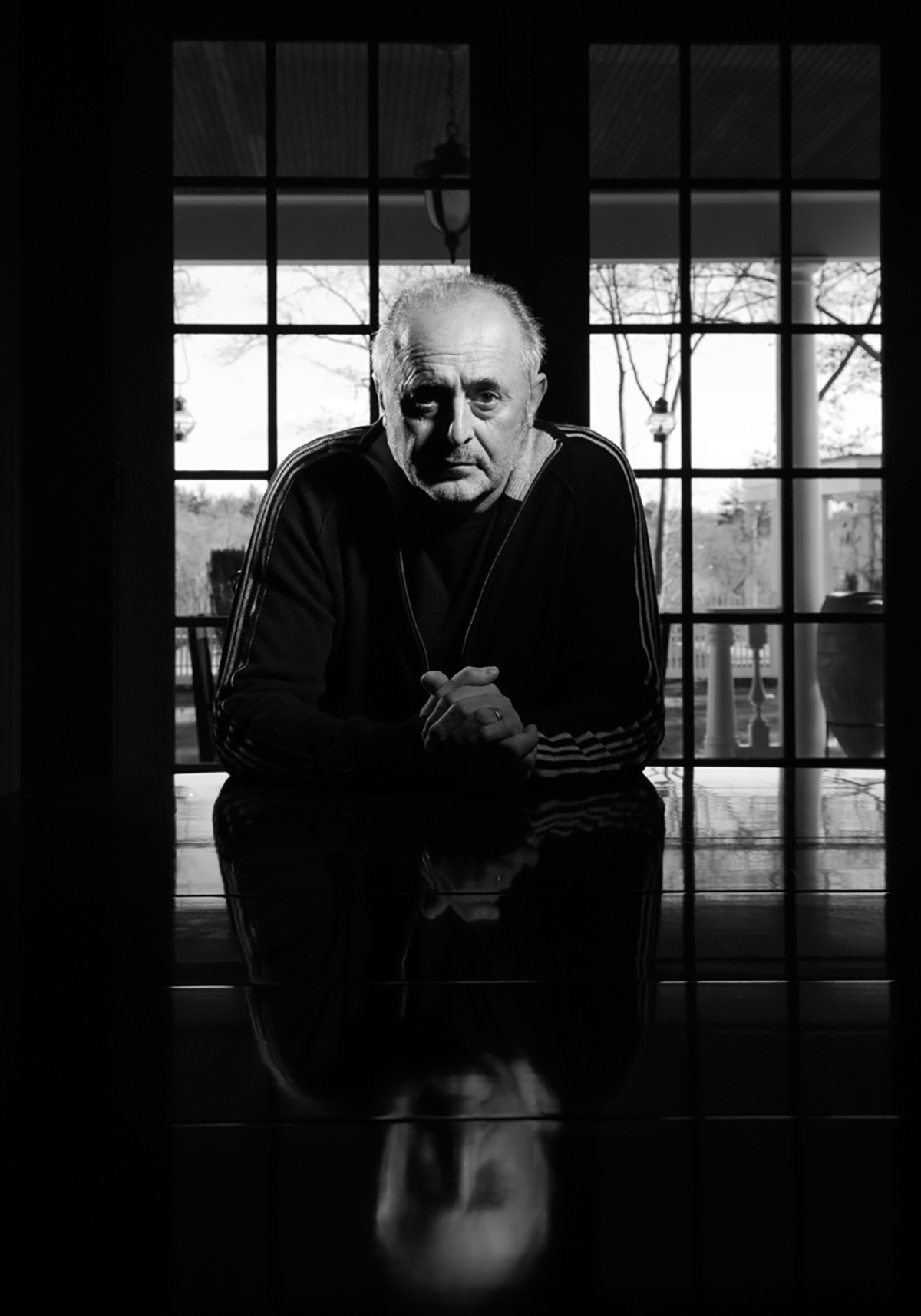

Photograph by Peter Tannenbaum

Let me tell you something: Luciano Manganella is a broken man.

At the Abe & Louie’s steakhouse on Boylston Street, he sips club soda and leans forward in the brown leather booth, bags under his eyes. He is smaller than his persona would suggest, and speaks in a voice too squeaky to be intimidating. Sixty-one now, and long ago gone gray, he still wears his fitted Seven jeans, paired today with a tight black T-shirt and a leather jacket. A few blocks away is the Jasmine Sola flagship store, the showpiece of the retail company Manganella built into an empire of expensive denim, designer loungewear, and cocktail dresses perfect for sorority formals. A month earlier, in October, New York & Company, Jasmine’s owner since 2005, announced it would shutter all 23 locations by February 2008. The prospect disgusts Manganella. He spent 35 years growing Jasmine into a multimillion-dollar boutique, and it took just two for New York & Company to run it into the ground. “They have done what I cannot even imagine people would do,” he says, in his thick Italian inflection.

But while he calls himself a victim, others say he is the one to blame for his stores’ downfall. With money came power, and with power—so say his accusers—came privileges for Manganella. Though he categorically denies all charges against him, six young women he employed both before and after New York & Company bought his chain allege that he sexually harassed them, his legendary temper keeping them quiet. Manganella was, and remains, a genius in his field. But it seems he failed to appreciate that the impulsive way he did business while turning Jasmine Sola into a Boston institution would be the very thing that would come back to doom his chance to turn it into something even bigger.

Now let Luciano Manganella tell you something: He is a passionate guy. Always has been.

When he arrived in Boston from the south of Italy in 1966, everything about New England excited him. Who knew that there were religions other than Catholicism, that there were cultures other than his native Salerno’s? The 20-year-old, unable to speak a lick of English, reveled in the adventure, the energy, the wealth of the place. “This country grabbed me like the wind,” he says.

Fashion wasn’t his plan then. But fashion was in his blood. In Salerno, Manganella’s father and brother sold fabric. One sister was a designer, and another worked in retail. In 1970, after a stint as a machinist, he heeded the family calling and opened a women’s clothing boutique with his new sweetheart, Vanda, a style maven herself, on Boylston Street (now JFK Street) in Harvard Square. Inspired by the flower-child vibe of the time, they called it Jasmine, adding the Sola when they introduced footwear to the inventory a few years later. The 275-square-foot nook held only 32 pieces of clothing on opening day, all stitched by their mothers.

The Jasmine Sola store in Harvard Square. (Photograph by Peter Tannenbaum)

Two years later, Manganella’s 18-hour workdays—mornings spent on the retail floor, afternoons in a Volkswagen bus buying fabric, evenings cutting the material, the rest of the time overseeing a growing team of seamstresses—began to pay off. He charmed his way into a lease on nearby Brattle Street. Now offering outside labels alongside Manganella’s own creations, the shop did solid sales.

He and Vanda, married now, moved to New York in 1983. By 1986 they’d separated, filing for divorce a year later. That same year, drawn to the other side of the business, Manganella started a fashion line of his own, Gruppo Americano. Ritzy department stores like Bergdorf Goodman and Neiman Marcus snapped up his collections, unable to resist the mix of Italian cuts and American sensibility, or Manganella’s seductively accented sales pitch. And as the rag trade fell for him, women did, too. “He was always charming and likable, and the girls working for me would say, ‘Oh, Luciano’s coming!’” says Tom Snowdon, a vendor who’s known Manganella for decades. “They were always flirting with him.”

Stacey Lehne was one of them. The striking 25-year-old from New Jersey was working in a designer’s showroom neighboring Manganella’s in Manhattan’s Garment District. A recent graduate of the Fashion Institute of Technology, she was eager to learn the trade. Manganella was apparently just as eager to instruct her. At a modelesque 5 foot 10, she was a knockout in any outfit, and for Manganella it was love at first sight. Stacey Lehne became Mrs. Manganella in 1994.

From Manhattan, Manganella continued to direct Jasmine Sola’s every move. He oversaw the hiring and operations, spearheaded all the buying. If Manganella didn’t like something, he told you straight up—a rare quality in an industry filled with backstabbing and double talk, and one that earned him the respect of peers, employees, and vendors alike.

By the late ’80s, the Cambridge store had become a destination for flocks of teenage girls and twentysomething women from both the city and the suburbs. They loved the young-and-cool but not intimidating feel and the spree-worthy clothing and shoes. Jasmine Sola was the first to bring Boston shoppers blockbuster labels like BCBG, Theory, Custo Barcelona, Guess, Vivienne Tam, and Juicy Couture. When cult footwear designer Steve Madden was just getting started, Manganella bought shoes from him out of the back of his van.

Manganella refused to resell any Jasmine Sola merchandise—either from the store line, or vendors’—to discounters like Filene’s Basement and Marshalls. He believed liquidation would hurt his brand, since the items would still bear Jasmine Sola tags as well as the designer’s labels. With that practice adding to Manganella’s status as an industry favorite, boutique owners from across the country visited his Harvard Square shop to study inventory and note what they should order next.