Different Strokes

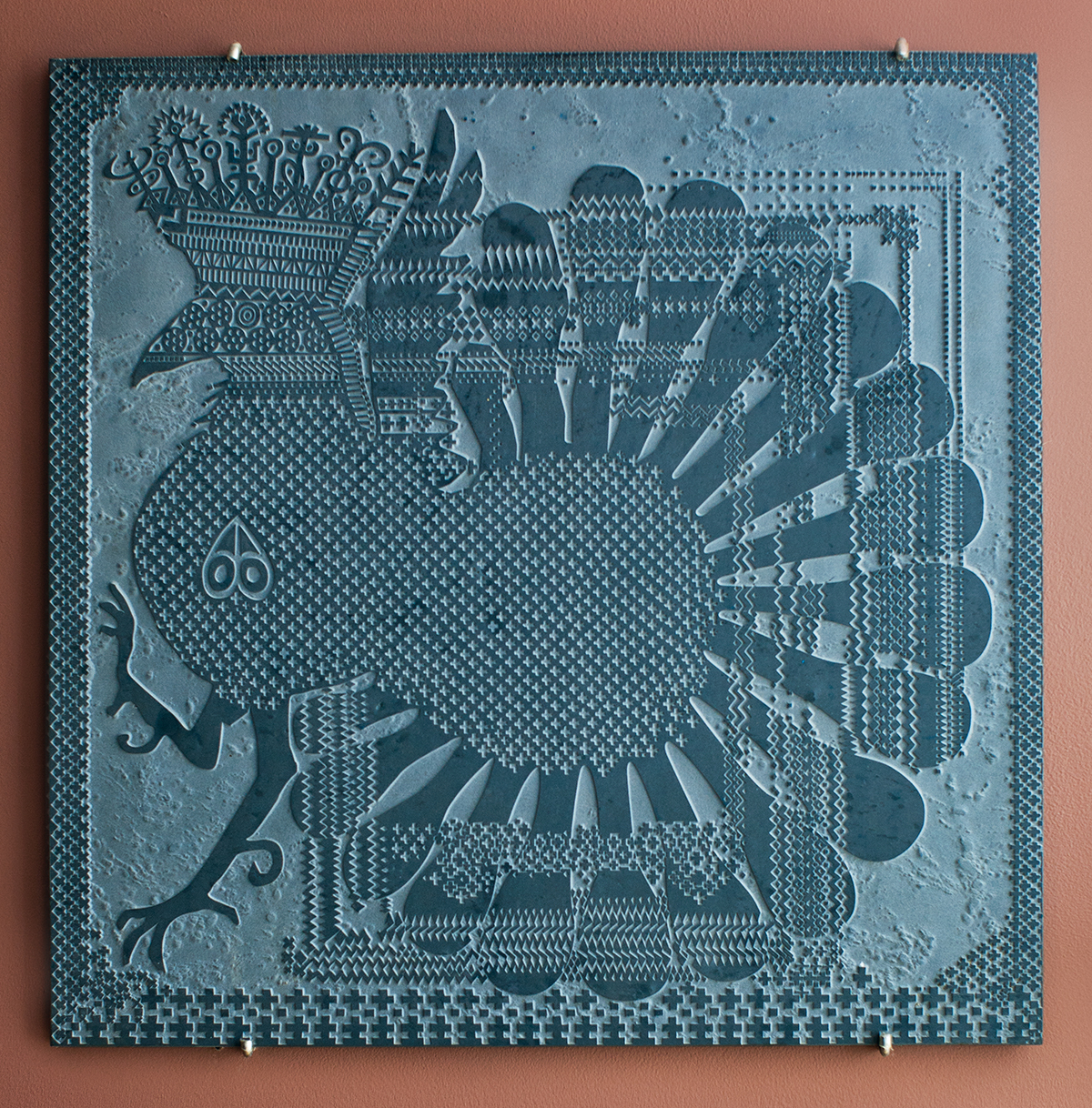

A Polish rooster sandblasted from folk art embroidery.

There are two things Will Reimann has been doing since childhood: rowing and creating. Growing up on Philadelphia’s Main Line, Reimann paddled boats and constructed model airplanes. He joined the crew team in high school, then continued to row on the Schuylkill while at Yale, where he received his BA, BFA, and MFA. Shortly after becoming an Ivy Leaguer, Reimann studied art under the tutelage of Josef Albers, the head of Yale’s art department at the time.

“So how did I get into Yale?” muses Reimann, a mischievous 76-year-old with a penchant for the occasional four-letter word. “I’ll tell you: shit luck.”

It’s a good thing luck was on his side. Reimann says that in the ’50s he and his classmates were “thrilled to work with experienced artists and artisans, sometimes as apprentices, until we gained sufficient fluency with a medium …. It was an absolutely captivating place to be.”

Reimann has never limited himself to a specific medium or art form. Since his grad school days, he has created works on paper, designed art and furniture out of stone and wood, and pioneered ways to use steel and Plexiglas in sculpture. Along the way, private collectors, cities, and museums — including the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, and the National Gallery — have purchased his work.

These days, Reimann and his wife, Helen, live in a carriage house in Cambridge. The lovely, sunny space is less than a five-minute walk from the Charles — convenient considering Reimann rows on the river every day (he has won the prestigious Head of the Charles race six times). On the art front, the spry septuagenarian has been focusing on small, idiosyncratic pieces using wood, metal, and stone. One such creation is a copper weathervane featuring a monkey wearing a top hat and peering into a telescope; his athletic stance is not unlike Reimann’s own. Another recent work is a partitioned pistachio bowl (one side for nuts, one side for shells) that’s carved out of mahogany and rosewood; it resembles an ancient Chinese seafaring vessel.

“A lot of things are waiting to get finished,” Reimann says, looking around his crowded home studio. “I tend to work on one thing until I get in a jam. Then I take a break by working on something else.”

With the exception of a massive aluminum starfish mobile dangling in one corner, it’s hard to see all the works in progress amid Reimann’s gadgetry. A conga line of tools hangs on a nearby wall; elsewhere there are gas and electric welders, a plasma cutter, a horizontal panel saw, and a 21-ton hydraulic pipe bender. Yet lingering in the shadow of one corner is an exquisite, two-foot-tall rhinoceros — carved out of long-leaf yellow pine.

Strewn at the rhino’s feet arecuriously carved stones, another unfinished project. These are what Reimann refers to as “river roundies,” ellipsoid granite and basalt rocks carved with organic patterns. To make each one, Reimann draws a freehand design, then transfers it onto a thin rubber sheet and cuts it out with an X-Acto knife. This becomes a stencil that Reimann then affixes to the stones before sandblasting them. He removes the rubber and voilá, detailed, delicate imagery. This is also the process Reimann uses for his large stone reliefs, which include fireplace surrounds and the 20 elaborate panels that adorn East Boston’s Piers Park, commissioned by MassPort.

As he did in college, Reimann still turns to the experts to learn new crafts, like he did with the T. H. McVey Stone Company, a stone cutting outfit in Watertown that builds rock walls, patios, and monuments. “I hung around there long enough, and a nice Italian kid, Paul Tucceri, gradually showed me the ropes,” says Reimann. “I believe in making things. We were made for physical work.”

Reimann grew up making model airplanes similar to this Piper Cub.

Files, placed in an orderly row, are among Reimann’s hundreds of tools.

Reimann enjoys the way light interacts with layered perforated screens — the granite in the foreground is a study for a commissioned piece.

The artist repairs a highchair he made in 1963 for his son, Christopher (it was later used by his daughter, Katya, and all five grandchildren).

One of Reimann’s “river roundies” featuring zoomorphic imagery.