Boston Doctors Are Providing Medical Care in Nicaragua

Dr. Henry DeGroot examines a patient in the hallway, a common location for the very sick. All photos provided.

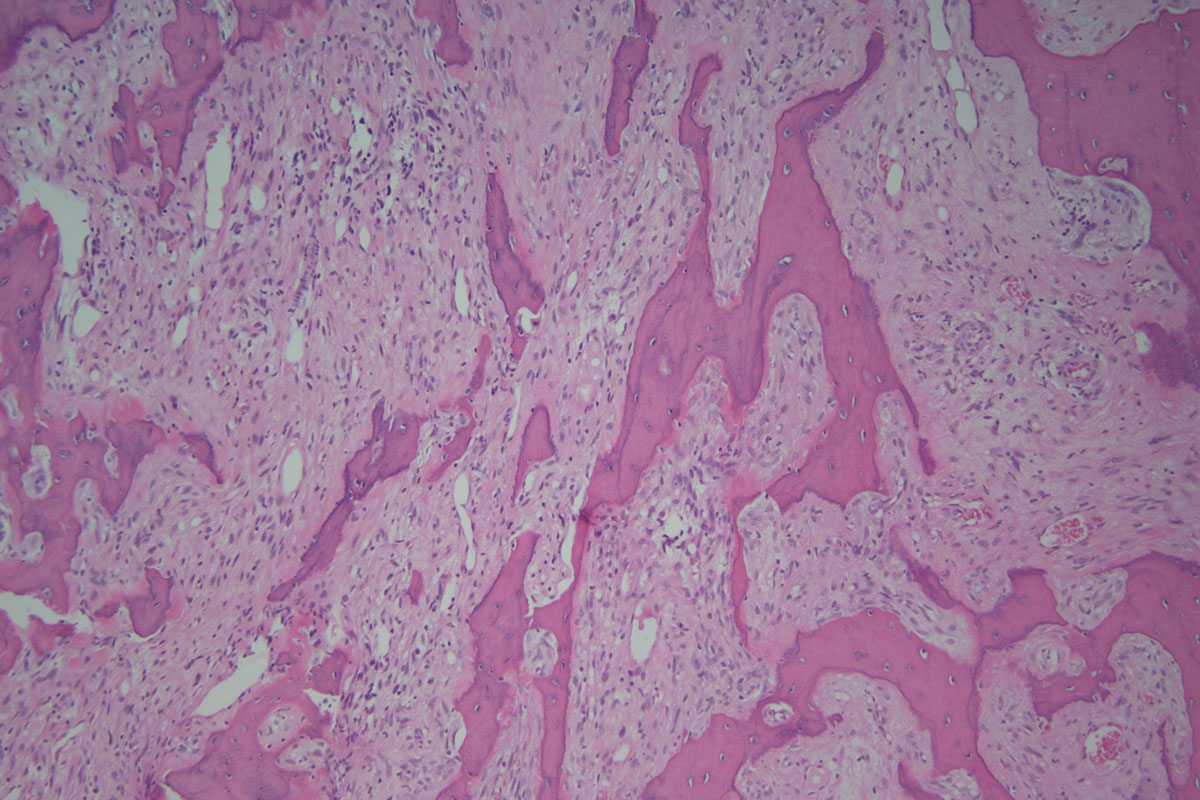

I knew it was going to be a bad tumor even before I put the slide on the microscope, due to the blue color of the tissue. But I also knew that this was no ordinary case. As the cells came into focus, a diagnosis of sarcoma came to mind, but my work was just beginning. This was foreign pathology, and unlike anything I see on a regular basis. The sample I was looking at traveled thousands of miles before landing on my microscope.

When 14-year-old Marisol came to the clinic in Siuna, Nicaragua, because of a tumor on her ankle, it was because her family heard that an American doctor would be there seeing patients. They made the almost 10 hour trek in the hopes that she could be seen. Tereza, 37, also made the trip, to have her wrist tumor evaluated.

They came to see Dr. Henry DeGroot, who made the 4,000-mile journey from Newton to see Marisol, Tereza, and 54 other patients. DeGroot, an orthopedic surgeon at Newton-Wellesley Hospital (NWH), has been making this trek for several years. Why Nicaragua? They need doctors like him. For the average citizen, access to non-emergency orthopedic care is nonexistent. Treatment for many congenital deformities and chronic conditions is not available in the public system. As a specialist in foot and ankle orthopedic problems, DeGroot’s skills are extremely important where 70 percent of the population is under 30 years of age. The complex reconstructive surgeries he performs are guaranteed to have a lasting effect.

In Siuna, a patient arrives at the emergency room by family members carrying her. There are no ambulance services.

Tufts Medical School has partnered with a non-governmental organization called Bridges to Community. Through the program, a team of physicians, nurses, medical students, and high school students all travel to the clinics in Siuna, living in dormitory-style accommodations with mosquito netting and no running water, all to see almost 140 patients a day.

Crowded hospital rooms are common.

The hospital in Siuna only has seven rooms: one for men, one for women, one for pediatrics, an obstetrics room, the emergency room, an operating room, and a consultation area. No elective surgeries are performed, only cesarean sections. There are no drugs for anesthesia or pain control, no cast materials, and no orthopedic instruments. Only minimal surgical equipment is available, yet the operating room is clean and effective. There are limited labs and x-ray capabilities. Things that we routinely toss out such as scalpel blades and needles are re-used due to a lack of supplies.

The nearest teaching hospital is the 340-bed Hospital Escuela Oscar Danilo Rosales Arguello (HEODRA) located in Leon, about six hours away. Because of this, in just one day, DeGroot and his team triaged 56 patients for 28 surgical cases. They spend the next four days operating non-stop.

HEODRA, a 340-bed public teaching hospital.

Every time DeGroot returns home, his suitcase contains tumor samples preserved in formalin in tightly sealed containers, hand-labeled with the identity of each patient he saw. At NWH, we process these samples into slides at no charge. The diagnoses are sometimes straight forward, while others can be very challenging. Such was the case with Marisol and Tereza’s tumors. I used all my available resources to work up the cases, but needed help.

I asked Dr. Christopher Fletcher, director of surgical pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a doctor known as an authority on soft tissue tumors, for his help. He, too, participates in medical missionary work, and diagnoses tumors from third world countries.

Fletcher carefully reviewed the cases, and as I feared, both tumors were sarcomas. Marisol’s was a Ewing’s sarcoma and Tereza’s an osteosarcoma.

Tereza’s tumor, an osteosarcoma.

I immediately called Dr. DeGroot with the diagnoses. Marisol and Tereza’s cancers are treatable with the appropriate follow-up after surgery, but assuring this occurs is perhaps the greatest struggle. The local hospital doesn’t have chemotherapy drugs, and oncologists are rare. Last year, DeGroot operated on another patient who turned out to have a Ewing’s sarcoma. She died three months after surgery because she was not able to get the proper post-op treatment.

Although situations like this can be heartbreaking, Nicaragua brings out the best in DeGroot and others that make the trip. They give to their patients, and the patients give back. This “pay it forward” outlook on life and medicine is honorable and a main reason why, even when faced with medical obstacles, the work is so rewarding.

Dr. DeGroot (left) teaching Nicaraguan residents how to perform a surgery.