Local Researchers May Have Found the Secret to Safe Tanning

Photo via istock.com/jcarrilet

Someday, you may be able to capture the coveted glow of a weekend at the beach—while actually protecting your skin.

A team of researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) have developed molecules that appear to safely tan human skin without UV exposure. What’s more, the molecules actually spurred cultured skin samples to produce eumelanin, the pigment that gives darker skin its color and helps protect it from potentially cancer-causing UV radiation.

The results were published Tuesday in Cell Reports.

“We are excited about the possibility of inducing dark pigment production in human skin without a need for either systemic exposure to a drug or UV exposure to the skin,” says David Fisher, the study’s leader and the chief of dermatology at Mass General, in a statement.

The work builds on a 2006 study also led by Fisher, which identified a topical compound that induces tanning in red-haired mice. Human testing came up short, though, likely because human skin is so much thicker than mouse skin.

After crossing that compound off the list, Fisher’s team expanded on the work of a group of Japanese scientists who found that blocking enzymes called salt-inducing kinases (SIKs) activates the pigmentation pathway and catalyzes tanning in mice.

Fisher’s team again had success testing SIK inhibitors on mice, but they failed to darken human skin. So Fisher called on Nathanael Gray, a cancer biology researcher at DFCI and a professor of biological chemistry and molecular pharmacology at Harvard Medical School.

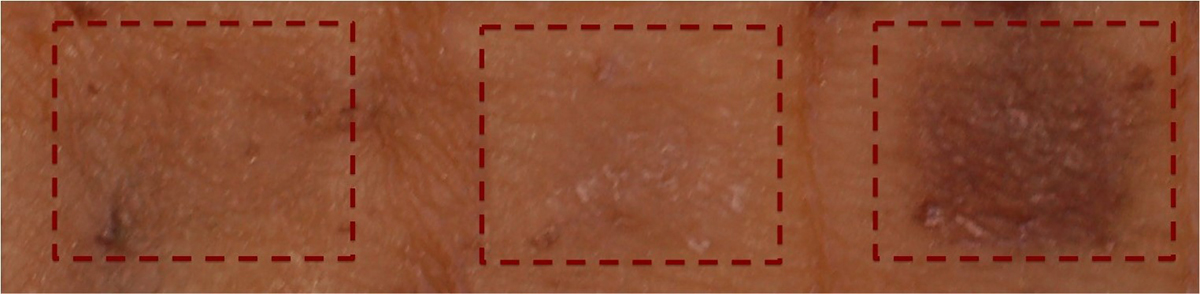

Gray’s lab created a new class of SIK inhibitors powerful enough to penetrate human skin samples. After eight days of topical application in the lab, the SIK inhibitors were shown to visibly darken breast skin samples and start the production of eumelanin. (See below.) The researchers believe the results would fade within several weeks, like a regular tan.

A joint patent based on the findings has been filed by Mass General and DFCI, but Fisher and his team caution that much more safety and efficacy testing is necessary before a consumer product could conceivably hit the market.

Still, in summers of the future, a SIK inhibitor cream could be a beach bag must-have both for tanning addicts and fair-skinned folks. It could, for example, offer protective benefits to redheads, who mainly produce a light pigment called pheomelanin, rather than eumelanin, and are thus at a heightened risk of melanoma.

“We need to conduct safety studies, which are always essential with potential new treatment compounds, and better understand the actions of these agents,” Fisher explains in a statement. “But it’s possible they may lead to new ways of protecting against UV-induced skin damage and cancer formation.”

Cultured human skin treated for eight days with a small-molecule SIK inhibitor (right) shows a significant increase in pigmentation. Areas treated with a control substance (left) or an SIK inhibitor less able to penetrate human skin (center) show no darkening/Photo courtesy of Nisma Mujahid and David E. Fisher at Massachusetts General Hospital