What If the Most Dangerous Person You’ve Ever Known Turned Out to Be Your Lover?

How an unsuspecting young woman helped bring a fugitive killer to justice.

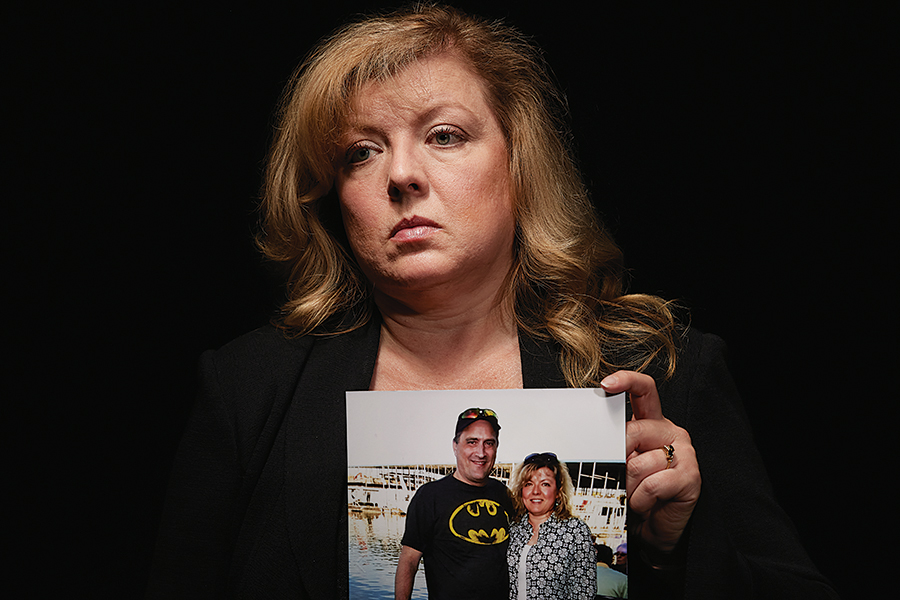

Noelle DesLauriers spent more than two years with her boyfriend before she learned his shocking secret. / Photo by Ken Richardson

After a long day of teaching special-needs students at a middle school, Lisa Ziegert hopped in her car and drove over to her night job at Brittany’s Card and Gift Shoppe in Agawam, a sleepy town 100 miles southwest of Boston near the Connecticut border. It was 4 p.m. on Wednesday, April 15, 1992, just a few days before Easter, and the 24-year-old with dark, curly hair, freckles, and blue eyes was scheduled to work until closing time at 9. Ziegert spent most of her shift putting helium into balloons as shoppers filled their carts with gifts and decorations for the upcoming holiday. At around 5:30 p.m., an unexpected visitor walked into the store: Ziegert’s sister, Lynne. It was a rare chance for the grown siblings to catch up, and they chatted about Ziegert’s job at the school, where she was beloved by students, and her future goals. After about half an hour, Lynne left the store and drove home, glad that all seemed well with her sister.

The following morning, Ziegert’s coworker, Sophia Maynard, showed up, as usual, to open the shop. When she spotted Ziegert’s white Chevy Geo Storm in the parking lot and saw that the store’s “Open” sign was still outside the door, alarm bells started ringing in her head. The front door was unlocked and the lights were on. A radio was playing in the background. Maynard called out Ziegert’s name, but there was only silence. She walked up to the cash register and saw that Ziegert’s car keys and purse were left behind. When Maynard walked into the storeroom to look for her friend, she noticed that the back door was open and several boxes had toppled over.

Maynard began to panic. In a flash, she ran out of the store and across the street to Alvin’s sandwich shop. “Something’s wrong,” she shouted. “Call the cops!”

Minutes later, investigators arrived at the store and found evidence of a struggle—shoe markings on the back door and a small amount of blood in the storeroom. The cash register was undisturbed; it did not appear to be a robbery. Local cops, aided by Massachusetts State Police detectives and the FBI, spent hours scouring the banks and watery depths of the Westfield River on foot and from the sky with a state police helicopter. Still, there was no trace of Ziegert.

Three days later, on Easter Sunday, a man was hiking with his dog along a mud-caked path in the woods 4 miles from the gift shop when he stumbled upon the body of a young woman. It was Ziegert. She had suffered seven stab wounds around her shoulder and throat, inches long and some more than an inch deep, and another knife wound to her upper left leg. Her light-blue denim skirt and blood-soaked white blouse were pulled down toward her ankles. The cuts on her hands led detectives to think she had not gone down without a fight. An autopsy would later confirm their hunch that she had been sexually assaulted. Police discovered foreign DNA, human blood, and sperm cells all over her clothes and body.

After the murder, fear spread through the town like a virus. Young women from Agawam and the surrounding communities signed up for self-defense classes in droves and insisted someone walk them to their cars at night. Noelle DesLauriers, a 22-year-old nursing student living with her parents in nearby Longmeadow, was one of the women gripped by the slaying. Day after day, she sat glued to the TV coverage of the case as police searched for Ziegert and her killer.

Weeks and months went by without a prime suspect in the case. When months turned into years, and no other murders were committed, residents began to relax, all but forgetting, it seemed, that Ziegert’s killer was still on the loose.

Nine months later, in January 1993, DesLauriers was in a patient’s house working as a home health aide when a breaking-news update shot across the television screen. Wondering if it might be a report on the unsolved Ziegert case, DesLauriers turned up the volume.

She soon learned that it was another local case that was unfolding in real time. Reporters were interviewing a man who said his infant son had been abducted. “Oh, my God!” DesLauriers told her patient. “I know that guy.” The abductee’s father was Gary Schara, whom she had briefly dated while they were students at Longmeadow High School back in 1986.

As she listened to Schara explain to the reporter that his estranged wife, Joyce McDonald Schara, and their son were nowhere to be found, DesLauriers’s mind flashed back to when she first saw Schara during their junior year. Fit and athletic, DesLauriers ran track and raced by Schara like he was standing still. He had just moved to the area from California and did not have many friends. But the two teenagers soon bonded over their mutual love of Agatha Christie novels, leading to a brief high school romance.

A few days after seeing him on the television, DesLauriers was surprised to pick up the phone and hear Schara’s voice on the other end of the line asking her out to dinner. They hadn’t seen each other since high school, but she remembered Schara fondly and agreed to meet him a few days later at Collegian Court, a historical restaurant and banquet hall in Chicopee.

When Schara walked in, DesLauriers was struck by how he looked. He was still tall and thin, and when they started to talk she realized he seemed like the same slightly shy guy she had known in high school. During dinner, Schara pulled out his wallet and showed DesLauriers a photo of his infant son. “Oh, he’s so cute,” she said. “I think it’s awful that he’s been abducted. I truly hope that you are both reunited soon.” DesLauriers, who felt sympathy for her former boyfriend, knew he was trying to rekindle their romance, but she was reluctant to get involved with him again. After all, she thought to herself, he had a lot of baggage at the moment.

One month later, the mystery of the boy’s abduction was solved when police found Schara’s son living with his mother, McDonald Schara, across the country in Seattle. Suddenly, what was once a kidnapping case was chalked up to a messy custody dispute. At the same time, now that Schara’s ex was in touch with law enforcement, she was more than eager to talk.

Through her attorney, McDonald Schara made a startling claim to Agawam detectives: Schara had killed Lisa Ziegert, she said, adding that he’d had an unusual obsession with the murder case. Agawam police had never heard of Schara before; he had no criminal record and there wasn’t any evidence linking him to the crime. Since the beginning of the investigation, detectives had been flooded with tips from angry former wives and girlfriends who tried to pin the murder on the men who had done them wrong. Detectives quickly placed McDonald Schara’s allegations against her ex into that category and dismissed the tip. Even her own family didn’t take McDonald Schara’s claim seriously. She had a long history of alcoholism, and at least one relative, according to news reports, said she was convinced McDonald Schara was just being a “crazy drunk.”

Mark Pfau worked the case from the beginning, starting in 1993 as an Agawam police officer with a 4 p.m.-to-midnight shift, during which he fielded phone calls and read the volumes of information about the Ziegert murder. But the leads went nowhere. In 2001, Pfau had been recently promoted to detective sergeant and took the reins of the case, determined to revive it after the original lead investigator retired. He was grateful for his predecessor’s attention to detail and meticulous bookkeeping. At the time, Agawam’s police department did not have a single computer; everything was typed and logged in by hand. But the files he inherited were pristine.

As a result of McDonald Schara’s shocking claim, Pfau asked to interview her former husband. He had declined an earlier request to sit for an interview, but this time he agreed. When Schara showed up at the Agawam police station a few months later in 2002, he was polite and cordial. But after Pfau asked him to submit a DNA sample to clear his name, things turned sideways: Schara refused to give a sample, saying he was scared of being secretly cloned.

Meanwhile, Ziegert’s family kept pressuring the police. Her mother, Dee Ziegert, appeared on an episode of the NBC crime show Unsolved Mysteries, which generated hundreds of false leads. Ziegert’s mother also organized charity golf tournaments to raise money for college scholarships, and took part in candlelight vigils in her daughter’s memory. “We want people to know that we will not forget, we will not give up,” she told a reporter. “Someone knows something and we hope that they will have the courage to come forward.”

Dee Ziegert was hopeful that one day, someone who knew who killed her daughter would come forward. / Photo by Dave Roback/AP

After DesLauriers graduated from nursing school, she began working shifts at several teaching hospitals in Boston. During that time, she met a prominent surgeon, fell in love, and got married. By then, she rarely crossed paths with Schara anymore, unless it was at one of the occasional high school reunion dinners her friends planned. When she saw him at an event in 2013, he was much heavier, she recalls. He had diabetes and weighed close to 300 pounds. Married, DesLauriers offered nothing more than a quick hello.

By March 2015, though, DesLauriers found herself alone and struggling through a messy divorce. In a Dear John–type letter, her husband had told her that he was ending their marriage. “I love you as a friend, but not as a wife,” he wrote. “I am not going to live for years in a bad marriage or relationship again.”

Heartbroken, she isolated herself for several months until her friend invited her to another high school reunion dinner. DesLauriers took it as an opportunity to get out of the house and see some friendly faces. Schara was among them. This time, DesLauriers noted, Schara had lost a lot of weight, and she thought he looked great. They had dinner together, and toward the end he wrote his phone number down and gave it to her, DesLauriers recalls, adding that Schara told her he’d like to get together sometime.

DesLauriers felt a twinge of happiness for the first time in months. Somebody was interested in her, and she was ready for companionship. “I know Gary and his family,” she told a friend. “It’s not like meeting some stranger on Snapchat.”

After a few months of dating, DesLauriers believed she had finally met Mr. Right. Schara had a steady job as a shuttle driver for Enterprise Rental at nearby Bradley International Airport in Connecticut, and he loved animals (a must for DesLauriers, who had two rescue dogs, Dora and Clouseau). He was especially good with children: At a birthday party for her friend’s two-year-old son, Schara played with him for the whole day. She thought he might be overcompensating because he had no contact with his own son, who was living with relatives in Seattle. When she asked him, Schara claimed those relatives had poisoned his son against him.

Schara was an attentive boyfriend to DesLauriers. He was quick with a bowl of hot soup whenever she got sick, and together they decorated Christmas cookies during the holiday season. Schara even drove one of her pets to the animal hospital after her dog had collapsed following a seizure, and then comforted her when she decided to put the dog down. When he wrapped his arms around her, DesLauriers noticed that he was crying, too.

An orphan, like the fictional Bruce Wayne, Schara had a deep affinity for Batman movies no matter which actor wore the dark cape and cowl. He had a collection of Batman T-shirts, and wore one proudly whenever he and DesLauriers went out to dinner. Schara’s adoptive parents had taken custody of him as a small child after he had bounced from foster home to foster home in California. The family eventually moved to western Massachusetts for Schara’s high school years.

Soon after they started dating in 2015, DesLauriers began to notice some odd behavior. For one, it seemed as though Schara suffered from anxiety around crowds. When they went to the Boston Marathon together two years after the bombings, she recalls, Schara became uneasy when he saw the fortress-tight security lined up along the route. She was startled when he became upset and refused to walk through the police checkpoint on Boylston Street, she recalls, and noticed that he was white with fear.

As time went on, DesLauriers began to wonder whether perhaps it wasn’t the crowds he was trying to avoid. One day, she recruited Schara to chauffeur her wheelchair-bound patient to the girl’s senior prom at a local country club. After the dance, the teen struggled with a disability ramp and nearly fell out of her chair. Schara rushed to the girl’s aid and saved her from catapulting out of the chair and onto the concrete sidewalk. The patient was okay, but protocol required DesLauriers to call 911. When police arrived, Schara was nowhere to be found. DesLauriers later learned he’d hidden behind the transportation van while the officers interviewed her about the incident.

There were other cracks in their relationship, too. She quickly realized he wasn’t really interested in sex, DesLauriers says. At first, she thought, Oh, my God, it must be me. Was I not dressed right? Did I not look right? She thought it was strange, but she enjoyed his companionship and didn’t want to end the relationship. Instead, she accepted the fact that Schara saw her as his platonic girlfriend. She had someone to spend time with, and for her that was a plus. After all, DesLauriers thought, Schara seemed in many ways like a safe bet, so why rock the boat? He didn’t drink or smoke. His idea of getting wild was wearing a T-shirt with a Bengal tiger print, and for him rocking out was listening to Billy Joel. He loved the song “An Innocent Man” and would often hum it on long car rides.

As the relationship deepened, DesLauriers wanted Schara to meet her family. Schara was interested in them, too, especially her famous brother, Rick DesLauriers, the FBI agent who led the investigations into the marathon bombings. Your brother, the FBI agent, I have to watch out for him, she recalls Schara joking. Schara charmed all of DesLauriers’s relatives, including her brother, whom he met at Easter dinner. After DesLauriers’s difficult first marriage that ended in divorce, her family saw her boyfriend as a new beginning.

Following a heartbreaking divorce, DesLauriers found love again with her old high school flame, Gary Schara, a man she thought she knew well. / Photo by Ken Richardson

By 2016, police were solving one cold case after another thanks to advancements in DNA evidence. With the Ziegert murder, that meant they were able to put together a digital composite image of the killer—a white man of European extraction with some freckling, dark eyes, and black or brown hair—using specimens found on her body. “All evidence and leads previously developed in this case are now being evaluated in view of this new forensic development,” District Attorney Anthony Gulluni said in September of that year, standing before reporters. “The technology that we have put to use is at the leading edge of the industry.”

With their mission renewed, State Police Trooper Noah Pack and Detective Sergeant Pfau once again began poring over the voluminous stacks of case files, focusing their attention now on 11 suspects who matched the new digital composite and had refused to provide a DNA sample when questioned. After taking the case to a grand jury, Gulluni received a court order granting him permission to force any unwilling suspect to provide a DNA sample—including Schara.

On Wednesday, September 13, 2017, Pack visited Schara’s residence in West Springfield, where he lived with his roommate in a two-bedroom apartment on the first floor of a large two-family home. At the front door, Pack told the man he was there to see Schara. The man informed Pack that his roommate was not home but said he would relay the message.

Later that day, Schara called DesLauriers and asked if he could stay at her place for the night. DesLauriers found the request a bit odd: After all, Schara never spent the night at her home during the week while he was working. But he told her that the traffic around his street was intense because of the hordes of visitors flocking to the gates of the Big E fair nearby, and he was worried about being late to work the next morning.

Schara arrived at DesLauriers’s home 20 minutes later and they settled into a relaxing evening of dinner and TV. The next morning, she woke up before dawn and got dressed for work while Schara slept. He opened his eyes just in time to give DesLauriers a quick kiss goodbye before she left for the day.

When DesLauriers returned home at 4:30 p.m. after an exhausting 10-hour shift, she noticed that Schara had left his wallet, his watch, and a handful of coins on the kitchen counter. That’s weird, she thought. His car isn’t in the driveway. Why didn’t he take his wallet with him? She tried calling his cell phone but the device was shut off, so she couldn’t even leave a message. DesLauriers went upstairs, took a hot shower, and changed out of her work clothes. When she walked back downstairs, she noticed a clipboard belonging to Schara on the coffee table. Attached to it was a letter with DesLauriers’s name written on top in her boyfriend’s near-perfect penmanship.

It’s a Dear John letter, she thought. Gary’s breaking up with me. History seemed to be repeating itself; she immediately flashed back to the heartbreaking note she had received from her ex-husband two years earlier, telling her that their marriage was over. Bracing herself for the inevitable, DesLauriers began to read. A few lines in, she gripped the clipboard tightly as her hands began to tremble.

“You are going to find out some awful things about me today. They will tell you I abducted, raped, and murdered a young woman approximately 25 years ago. It is true. All of it. I had no intention of killing her when I grabbed her but events spun out of my control. And in the eyes of the law it is all the same. I have never regretted anything so much…. I always knew one day it would catch up to me & now it has. I received a text [from my roommate] last night that the state police were at the house with important papers for me. That will be a warrant to take DNA & that will send me away for life…. I have never really been or felt normal. From a very young age I was fascinated by abduction & bondage. I could never keep it too far from my mind for long. On that fateful day, I let myself do something terrible. I’ve never forgiven myself of that…. I also never did anything of the like again. I hated what happened. I despised myself. I thought of turning myself in hundreds of times over the years but I am truly a coward. Today it will all end. I will either take my own life or face the music as it were…. —G.”

The next two pages included Schara’s last will and testament and also a letter to Ziegert’s family, in which he expressed remorse for the slaying and wrote that he could never apologize enough for taking their daughter and sibling’s life. “I neither expect or deserve your forgiveness,” he wrote. “But I hope knowing who [I am] and knowing I am gone will bring you some closure & peace. I am so truly sorry. —GES [Gary Edward Schara].”

At first, DesLauriers didn’t believe it. “I thought that he was having a psychotic breakdown and that he’d only imagined that he had committed this heinous crime,” she says. “That he was just pretending that he did this.”

Even though she had her doubts, DesLauriers knew she had to give the letters to the cops. She scrambled into her car and drove to the Massachusetts State Police barracks in Westfield.

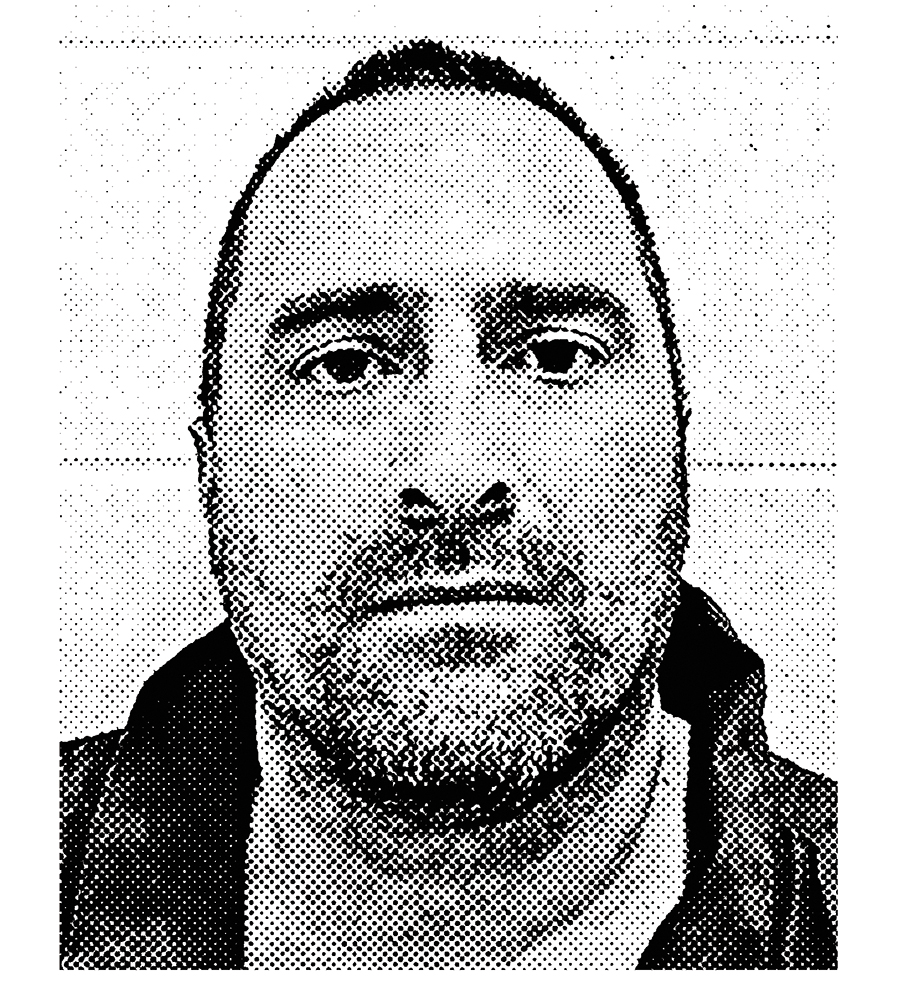

Gary Schara seemed like Mr. Right: He didn’t drink or smoke and was a dedicated boyfriend. / Photo courtesy of HOGP/AP

Wiping away tears, DesLauriers ran into the station and asked to speak with someone working on the Ziegert case. Investigators were stunned when she showed them the letters. They had believed DNA would eventually identify Ziegert’s killer, but they never thought they would see a confession, especially in a note from the murderer to his girlfriend. Police interrogated her into the night, asking hundreds of questions. Most important of all: Where was Schara? After saying she was afraid that he’d committed suicide and was hanging from a tree somewhere, DesLauriers added that she still loved him very much.

In Agawam, Pfau got a call from the state police, jumped into his squad car, and raced to the barracks to read the letters for himself. He stayed silent as he digested every word.

“It’s him, isn’t it?” one of the state police investigators asked Pfau. “It’s Lisa Ziegert’s killer.”

“How’d you know?” Pfau asked.

“Because the hairs on your neck are standing on end,” the investigator said.

To Pfau, the letters did not reveal a full confession. After all, Schara didn’t detail much about the crime. But it was clear to the veteran detective that Schara was attempting to clear his conscience.

The case had finally come full circle. Pfau reflected on a visit he had paid to Joyce McDonald Schara’s relatives in Seattle, where they told him she had received a music box, like the ones sold at Brittany’s Card and Gift Shoppe, from her then-husband on the night of Ziegert’s murder. Now, holding the confession in his hand, Pfau told his fellow investigators, “We’ve got to find this guy.”

Detectives pinged Schara’s cell phone and tracked its GPS coordinates to Stafford Springs, Connecticut. It was just past 10 p.m. when police found his black Honda Civic in the parking lot at Johnson Memorial Hospital. There was no sign of Schara, but he had left a suicide note on the dashboard: “To whomever finds my body, I apologize for any psychological trauma incurred. Call Mass state police. Thank you, GES.”

Hours earlier, Schara had swallowed a fistful of ibuprofen—but he immediately grew terrified of dying and walked into the emergency room, where doctors pumped his stomach and admitted him overnight. He was then put into the critical-care unit and, once detectives arrived, they placed him under arrest as a fugitive from justice.

Meanwhile, Massachusetts State Police searched Schara’s West Springfield apartment and DesLauriers’s home. As officers swarmed her place, DesLauriers called her brother, who was driving to his

corporate-security job at Penske Corporation in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where he had been working since he retired from the FBI. “Gary is under arrest for the murder of Lisa Ziegert,” she told him. “Now I have police coming to my house looking for evidence.”

The former special agent spun his car around in the middle of the road and headed back home to focus all of his energy on helping his younger sister, if even from afar. “Be compliant,” he advised her. “Investigators have their job to do.”

“Of course I’m going to be compliant. I can’t believe this is happening,” she said, sobbing. “How could I have dated him for more than two years without knowing who he really was? Am I gullible?”

“We all liked Gary,” her brother told her.

DesLauriers waited outside her home while investigators searched each room for evidence. They took Schara’s toothbrush and a full syringe of insulin used to treat his diabetes. They even searched the well under her house, and the cereal boxes in the kitchen cabinet.

In the end, the DNA results were conclusive: Saliva found on Schara’s toothbrush tied him to the decades-old crime. He was then extradited from Connecticut back to Massachusetts, where police formally charged him with the murder, aggravated rape, and kidnapping of Ziegert. “When we finally put him in a jail cell,” Pfau says, “he sat on the bench, leaned up against the concrete wall, and just exhaled. It was finally over. There was no more looking over his shoulder.”

Two days after Schara’s arrest, DesLauriers celebrated her birthday. When she received a bouquet of flowers at her home, she opened the small envelope tucked into the arrangement and saw it was from Schara. She later learned he had placed the order days before the police finally caught up with him. Schara continued to send DesLauriers cards and letters during his incarceration. “He went to jail, and at that point, part of me was still thinking about him as my boyfriend,” she says. “I couldn’t make that change in my head that he wasn’t.”

It took DesLauriers several months to work up the courage to visit Schara at the Hampden County Correctional Center. She waited for him on one side of a Plexiglas partition until he arrived in a red jumpsuit and sat on a stool on the other side. Over the jailhouse phone, he attempted to make small talk, telling her that the food was not so bad and that his brother had sent him some books. After listening for several minutes, DesLauriers stared into her former boyfriend’s dark eyes and unloaded. “You lied to me and to everybody for 25 years,” she screamed. “I am going to come back someday and you are going to tell me why you did this. You owe me that. Not only do I deserve it, but everyone else who’s a part of this nightmare that you’ve created deserves it. The Ziegert family will never have their daughter back. She had her whole life ahead of her.” Schara stared blankly back at her. He did not say a word.

DesLauriers left the jail and maintained a low profile, refusing to do media interviews and choosing not to appear at any of her former boyfriend’s court hearings. “I was in debt because of my divorce and I was terrified that I would lose my job,” DesLauriers says. “Who wants a nurse that had dated a murderer caring for their critically ill child?”

DesLauriers did pen a letter to Ziegert’s mother, Dee. “I know that nothing can ever bring your daughter back,” she wrote, “but I hope that you are at least comforted by the fact that justice has been served.” DesLauriers says that Dee telephoned and thanked her for the note.

In 2019, Schara returned to court and changed his plea from not guilty to guilty of first-degree murder with extreme atrocity and cruelty. He was given a life sentence, to be served at MCI Norfolk, with no chance of parole. Another judge ordered him to cease all communication with DesLauriers.

The Ziegert case may have finally ended, but for DesLauriers, the ordeal still lingers. The week before Easter this year, 29 years after Ziegert’s murder, DesLauriers stepped out of her cherry-red Mazda CX5 and into the warm sunlight of early spring to explore the darkest of all places, the woods off Suffield Street in Agawam, where Ziegert’s body was found.

Wearing a bright-blue blazer and matching scarf over a black sweater, designer jeans, and boots, DesLauriers was not dressed for a hike, but she began walking through overgrown heath and bramble anyway as dead, brittle leaves made crunching sounds beneath her boots. Thorns from an extending briar patch grabbed hold of her jacket, pulling her back, almost preventing her from moving any further down the dirt path. She broke herself free and kept walking before eventually stopping about a hundred yards into the woods and lowering her head toward the ground. “My hair is standing on end right now,” she said. “I can just imagine her being here in the cold and the dark, screaming, and no one can hear her. She’s injured and someone is tearing at her clothes. Her last moments were just awful. Just to be left here like this. It makes me want to vomit. I mean, what kind of person does this?”

In the months after learning her boyfriend was a killer, DesLauriers fell into a deep depression and sought professional help. Standing at the crime scene, she admitted she is still on the long journey toward healing herself. “My life is pretty horrible right now,” she said. “But I have my friends and family, and without their support, I wouldn’t even know why I’m here.” Through the years, she has replayed scenes from her relationship with Schara over and over, looking for clues she missed. More than anything—despite the fact that police praised her decision to hand over Schara’s confession letters—she continues to grapple with whether she was a victim, or a villain, because she once loved a killer.