Has Witch City Lost Its Way?

They’re hip, business-savvy, and know how to cast a spell: How a new generation of witches and warlocks selling $300 wands conquered Salem.

Photo illustration by C.J. Burton

On a recent afternoon, visitor traffic was light at the Salem Witch Dungeon Museum. Outside, near several stockades, two bored-looking husbands sat on a bench, languidly scrolling through their phones as their wives stood alone in a queue, waiting for the museum’s next reenactment to begin. A few blocks away, at the Witch History Museum, a handful of families mulled around outside, taking selfies and consulting maps before continuing their strolls through town. Inside, the museum itself was nearly empty, save for a couple of employees in the gift shop.

On this day at least, it seemed as if delving into the history of the Salem witch trials was not the main attraction. Instead, most visitors were packed into a few blocks of Essex Street, the city’s commercial hub. There, tourists lined up at the Witch Mansion, billed as Salem’s “premier haunted house.” Nearby, throngs of visitors clogged storefronts, perusing window displays and sale racks. The demographic skewed young, female, and (dare I say it?) decidedly witchy: lots of black midriff T-shirts and crystal necklaces; harem pants bedecked with metallic suns and moons; and Chuck Taylor high-tops in spider-web prints.

Inside Hex: Old World Witchery, one of Salem’s twenty-some witch-themed stores, masked customers were packed uncomfortably close that afternoon, bumping elbows and shopping bags as they browsed essential oils and tarot cards. At a display case, a middle-aged woman deliberated over a pair of elaborate custom wands.

“I just can’t decide,” she complained to her shopping companion.

“Which one most speaks to you?” counseled her friend.

The woman closed her eyes in deep contemplation. “This one,” she finally said, selecting a wand made of ash and copper and retailing for $300.

The sales clerk promptly wrapped the customer’s purchase in tissue paper, offered a few suggestions for its use, and wished the two women well before turning to the small queue that had developed behind them.

Similar versions of this scene played out at other witch-themed shops up and down Essex Street that afternoon, and as the dinner hour approached, the crowds of magic-enthused shoppers showed no signs of stopping. Some of them self-identified as practicing witches—members of a nature-based religion that emphasizes an embrace of goddess ideology and the need for balance between masculine and feminine forces. Others said they were witch-curious: merely interested in a spell or a potion to help manifest a wish or a goal in their lives.

They are far from alone. The popularity of witchcraft is a growing national trend. Twenty-first-century witchcraft, including its commercial products and services (such as psychic readings), is big business, netting about $2 billion annually in the U.S. In many ways, Salem has become a mecca for this, with as many as 5,000 of its 43,000 residents identifying as practicing witches and untold thousands passing through as part of a spiritual pilgrimage. Witchcraft also drives much of the tourism in Salem: More than one million visitors descend on the city each year, spending about $140 million annually, a chunk of it at stores like Hex. Officials here also estimate that 35 percent of Salem’s annual tourism revenue is gained in October, when the city hosts Haunted Happenings, a monthlong celebration that includes everything from a yoga retreat at the Satanic Temple to an official Witches’ Halloween Ball.

Along with self-identified contemporary witches and dabblers looking for potions or spells are throngs of visitors who arrive in Salem claiming descendancy either from the Colonial settlers involved in the 1692 witch trials or other individuals accused of heresy and executed in early America. Salem State University history professor Emerson Baker estimates that today, those descendants number about 100 million. Members of the coven include politicians such as both Bush presidents and celebrities such as Sarah Jessica Parker and fashion designer Alexander McQueen, whose ancestor Elizabeth Howe was one of the first women to be condemned and hanged in Salem in 1692 as part of the quest to eradicate supposed witches.

While I am certainly no such luminary, I also count myself among those numbers. My ancestor Mary Dyer was hanged in Boston in 1660, 32 years before the Salem witch trials. The reasons I’ve heard for her execution are vague. At the time, her accused offenses were a convoluted combination of heretical religious beliefs and the defiance of a banishment order. That she had also given birth to a badly deformed stillborn baby was thought to be further proof of her estrangement from a Puritanical God and evidence of her wicked ways. Since Dyer’s execution, many generations have struggled to make sense of her legacy: Was she a religious martyr? (Dyer practiced and preached an early form of Quakerism.) A nasty woman? A crusader for social justice? For as long as I can remember, I’ve watched my own family reckon with how to identify Dyer and the cultural inheritance she left behind.

Similarly, Salem has spent many lifetimes grappling with its legacy as a place where people like my ancestor fell victim to society’s worst impulses. Now, as our nation as a whole works on how to address and repair some of the more shameful moments in its history, with southern cities removing their Civil War monuments and academic institutions reconsidering the names of buildings, some are wondering whether it’s time for Salem to finally do the same. Is a witch-based tourism economy the best way to honor the legacy of executed individuals who weren’t even witches in the first place? Or is continuing to transform the town into the epicenter of modern-day witchcraft actually the perfect way to right the wrongs of the past?

Today, witch-based tourism is a pillar of the city’s economy. / Photo via the Boston Globe/Getty Images

As a child, I often thought of my ancestor as a Hollywood witch, someone capable of casting dramatic spells and defying the basic laws of physics. Maybe more important, I imagined that she had somehow transmitted those abilities to me. By the time I was a teenager, I’d mostly given up on my hopes for psycho-kinetic inheritance and instead touted Dyer as a fearless agitator for women’s rights, a totem for my own awakening on issues of gender inequality. I piously visited her commemorative statue at the State House and traveled to Salem, certain I’d feel some kind of transcendental connection with the women executed there. I kept tarot cards in my underwear drawer and wore pointy hats on Halloween.

If I’m being honest, in each of these iterations, what I was really looking for was justification for my own ideals and identity: first as an awkward kid who wanted to believe she had special untapped abilities that could help her navigate (or destroy) middle school cliques, and later, as a young woman looking to feel emboldened on her political journey.

Like me, Salem has also grappled with its identity in the shadow of its ghosts. The city always suffered from “mixed feelings about its legacy,” says Baker, the author of A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience. After the trials, the city’s reputation as an epicenter of intolerance and persecution only grew as writers ranging from Massachusetts’ own Cotton Mather and Nathaniel Hawthorne to Benjamin Franklin forever immortalized it in their works. As the centuries passed, Salem residents remained sharply divided on how to respond to the past. Many townspeople preferred to ignore the tragic moment in history altogether, while descendants of those accused and executed pushed for somber memorials and political pardons.

For a very long time, Salem took neither of those paths. Instead, it sought to capitalize on the trials to draw visitors. In 1880 the city issued its first tourist guide, which made bold mention of the witch trials and key sites associated with the main participants on both sides. In the years leading up to the 200th anniversary of the trials, the city doubled down on its tourism strategy, introducing cartoonish witch imagery as part of its official PR branding, as well as souvenirs ranging from commemorative images to witch-inspired face creams. As far as historians can gather, it was around this time that Salem earned the moniker “Witch City.”

By the first half of the 20th century, though, enthusiasm for the city’s connection to the 1692 trials began to wane. City elders made conscious decisions to omit mention of them in various historical documents and rejected attempts to build a memorial to victims. Despite these efforts, the presence of the witch in Salem’s popular identity refused to vanish. Around 1940, Salem High School adopted a caricature of a haggish witch as its mascot. After the success of Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, other iconography began to appear as well. Today, even the patches on city police uniforms include a depiction of the witch figure.

Perhaps no single event did more to popularize Salem’s connection to witchcraft than the 1970 decision by ABC to film several episodes of the smash TV show Bewitched here. The arrival of its star, Elizabeth Montgomery, who played 20th-century witch Samantha Stephens, made headlines in regional newspapers, including the Boston Globe. A cover of the nationally distributed TV Guide featured a smiling Montgomery backed by dozens of enthusiastic Bay Staters who had turned out to see her in person. The headline read, “Samantha Goes Home: Salem, where they once hanged them, turns a witch into a tourist attraction.” Around the same time ABC aired the episodes filmed in Witch City, Salem began enjoying the bump in tourism first prophesied by the media.

Samantha arguably did more than conjure a veritable boom in witch tourism; she also set the stage for the next phase in Salem’s relationship with witches: as their modern-day home. A glimpse of what was to come can be seen in an episode where the character is confronted with a sign bearing one of the city’s favorite emblems—an old crone of a witch wearing a pointy hat and riding a broom. Samantha the TV witch is outraged. “That’s disgraceful,” she shrieks. Her mother, also a witch, agrees, and promptly changes the image into a gorgeous young blond woman.

Witch Erica Feldmann’s store is the place to find everything you need for a witchcraft-inspired home makeover. / Photo courtesy of Hauswitch

If ever there were an embodiment of witchcraft’s new look, it would be HausWitch Home + Healing. Having been referred to as West Elm for witches, the boutique features high ceilings, exposed brick walls, and an airy Scandinavian-design vibe. Its shelves, meanwhile, are artfully stocked with everything from throw pillows with magical designs ($88) to tarot card decks ($50) to its signature “HausCraft Spell Kits” ($39-plus), including one for clearing stale energy out of a home that includes rosewater in a spray bottle, a potion, a bell, a selenite crystal, a candle, and a postcard with instructions for casting the spell. (If you’re trying to manifest your dream home or get along better with roommates, there are kits for that, too.) Erica Feldmann, the store’s proprietor, says people travel from across the globe to visit, with one even coming all the way from Dubai.

Feldmann, who also goes by HWIC, or Head Witch in Charge, has a hipster vibe and looks more like Samantha by way of Somerville than a gnarled witch of yore. Her current stint as one of Salem’s most popular and successful witches began when she was a graduate student in gender and cultural studies at Simmons University and started offering low-budget but soulful home makeovers to her classmates based on the values and aesthetics of witchcraft—think: feng shui for witch-inclined millennials. In time, she began to include her spell kits as part of her design plans and started a blog about her projects, which eventually led to a popular book, HausMagick: Transform Your Home with Witchcraft.

Feldmann’s boutique may be one of the most popular of the many stores owned by witches in Salem, but it’s safe to say it wouldn’t be here today if it weren’t for Laurie Cabot, who opened up the first witch shop in Salem in 1970, when there were no witches practicing out in the open, to sell herbs for magical uses, potions, and other tools of the trade. Despite plenty of opposition from religious residents and other haters, she stuck it out, earning the attention of the media and even then-Governor Michael Dukakis, who dubbed her Salem’s official witch.

Christian Day, a well-known warlock in Salem, and his husband have built what Day calls an “occult empire” that is set to bring in $3.5 million in revenue this year. / Photo via Joseph Prezioso/Getty Images

Inspired by Cabot’s success, other witches soon began settling in Salem and opening their own businesses. Today, witch shops and psychic studios line Essex Street, drawing legions of tourists. Among them is Hex, home of the $300 wands. Co-owner Christian Day, who has touted himself as “Salem’s Most Famous Warlock,” grew up on the North Shore and studied under Cabot. On his website, he unapologetically refers to Warlocks, Inc., the umbrella company owned by Day and his husband, Brian Cain, as an “occult empire,” which hardly seems an exaggeration: The company has garnered seven figures annually for the past several years and is on track to hit $3.5 million in revenue this year.

In addition to Hex and its outpost in New Orleans, where Day and Cain (also a warlock) live for most of the year, the couple own Omen, a psychic parlor and witchcraft emporium on Essex Street, with a location in New Orleans, too. The pair also run a tour company, a publishing house, and a psychic hotline. But perhaps nothing does more to promote Salem as a mecca for modern-day witches than the events that Day and Cain put on here.

When I spoke to Day in early July, I struggled to hear him over his new espresso machine (Oprah’s favorite, he proudly noted over the sound of frothing milk). He told me he was busy registering last-minute vendors for the October Salem Psychic Fair and Witches’ Market, and that the October Salem Witches’ Halloween Ball had been sold out for months by then, as had a three-course Mourning Tea scheduled for late Halloween morning.

Despite the popularity of their shops and events, some see what Day, Cain, and other witches around town are doing as nothing short of commodifying a religion and spiritual practice for personal gain. Day, for his part, is quick to defend his actions—and earnings. “It’s okay to be commercial. More than that, it’s extremely important for the witches of Salem to be seen as successful,” he says. “How does it help us to socialize our religion if we are under the heels of society? If every witch is in a state of financial distress, how does that help our civil rights?”

Other witches I spoke to said variations of the same thing. They are human; they have car payments and rent due each month. “Many years ago, people paid for our services with a dozen eggs,” says Lori Bruno-Sforza, another well-known Salem witch and shop owner. “We have to pay our bills. Yes, we need to profit. We also need to give back.” And it appears they do.

Despite the witch consumerism that I saw on display when I visited Salem, I also noticed remarkable generosity. Erica Feldmann, for instance, has designated HausWitch as a drop-off area for Solidarity Northshore and advocates for everything from affordable housing to access to reproductive healthcare. Lorelei, Salem’s love clairvoyant and proprietor of Crow Haven Corner, founded Salem Saves Animals, a nonprofit dedicated to animal rights. Bruno-Sforza orders teddy bears by the carton to hand out to kids who visit her store. She couldn’t meet me there when I was visiting because she was at home with her dogs, recovering from double knee-replacement surgery (like Cabot, Bruno-Sforza is in her eighties). Instead, she asked her son Anthony, who also performs psychic readings, to speak with me. When I had to delay because of car trouble, he immediately texted to make sure I was okay. When we finally rendezvoused, he gave me a rose-quartz pendant and a thank-you card his mom had sent along. And though Cabot and her daughter were holed up in a motel room after remnants of Hurricane Henri flooded their house, they happily postponed a consultation with their insurance company to answer my questions about their time in Salem and offered a free reading the next time I was in town.

It’s easy to see why so many people are drawn to that kind of energy. While there are plenty of kitschy stores in Salem peddling hats and brooms, the modern-day witches I met are peddling something different. Sure, Feldmann sells ornaments emblazoned with black cats and cartoon witches at HausWitch. But she also stocks posters emblazoned with slogans including “Hex the patriarchy” and coffee mugs suggesting that “Witches are the future.” She’s selling the mug, sure, but she’s also selling “intersectional feminism to people visiting Salem,” she says. Maybe the real question is whether the rest of us are ready to buy it.

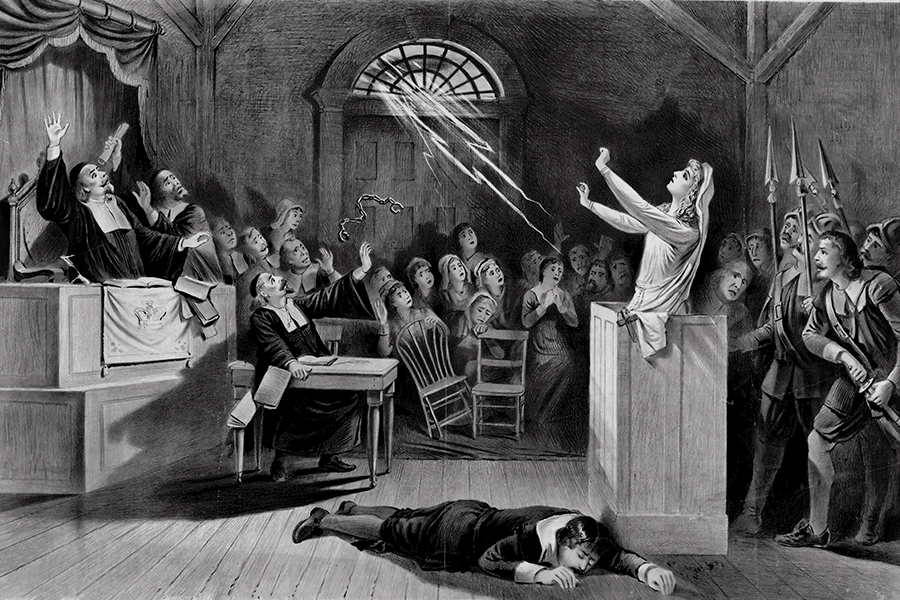

A rendering of the Salem witch trials. / Photo via Niday Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo

Even if we accept that it’s a good thing for witches to be making bank, is Salem the right place for that? Are witch-themed boutiques and events the best way to consecrate the site of a human rights atrocity, to honor and teach the history of what happened here? Or does it only confuse the history instead of enlightening people about the past? Donna Seger, a professor of history at Salem State and the author of the popular Streets of Salem blog, says one of the most common questions visitors ask her is how they can find the spot where the witches were burned. “And I have to tell them that they weren’t actual witches and they weren’t actually burned,” Seger says. “The public seems very naive and uninterested in the real story. As an educator, that concerns me.”

Much of this tension was depicted in a documentary by Joe Cultrera titled Witch City, which explores the conflation of history, consumerism, witches real and accused, and Halloween. “Telling the true story of what happened in Salem is important. But most people come looking for a spooky time and a place where they can put on their witch hats and run around having fun,” he says. “Salem has morphed into a brain-dead Disneyland. That is the

antithesis of who the 1692 victims were.”

It’s a sentiment I heard repeatedly from longtime residents in Salem, and one that Emerson Baker says he continues to see in his research today “as the town actively comes to grips with the long shadow of the trials” in the midst of commercialized “haunted happenings, a desire for social justice and peace” for the persecuted, and a contemporary witch community.

In 1992, the city took a major step toward creating a solemn space for commemorating the past when it erected a monument to the people killed in the trials. But reckoning with America’s dark history isn’t just about erecting—or toppling—monuments. It’s about how we live on a daily basis. And many of Salem’s successful modern-day witches argue that there is no better way to honor those who lost their lives to intolerance and society’s divisions than through a booming and successful community (and economy) spreading a gospel of tolerance and inclusivity.

When Cabot first moved to town, some Salem residents immediately demanded the city close down her shop. Her daughters were so bullied at school that Cabot was forced to homeschool them. Parents and religious leaders protested when she was invited to give talks about the theory and history behind her craft. Around Halloween, which coincides with the pagan religious festival Samhain, congregants from evangelical Christian churches would descend upon the city to protest Cabot and her followers, sometimes filling the streets and sidewalks with angry signs and bullhorns.

Despite this, Cabot stood her ground and continued to spread her work and philosophy centered around positivity and love—and in so doing became a leader in the world of contemporary witchcraft. The author of several books, her message of acceptance and the importance of tapping into one’s own inherent powers was, for many, a welcome corrective to the social and political milieu of 1980s America. Academics touted her as a leading voice in second-wave feminism. College students, housewives, and would-be executives trapped below the glass ceiling flocked to her workshops and classes—and many of them ended up staying in Salem. “So many of us had been practicing in isolation,” Cabot told me. “People began stepping forward and claiming their identities. They began realizing there was strength in community.”

Fast-forward to 2021, and the movement Cabot built has won over many people who arguably would have been critics in past generations. “This is a community that prides itself on respect and love,” says Steven White, the lead pastor at the First Baptist Church of Salem. “People come here because they can freely be themselves. More and more Americans are looking for a spiritual anchor. Maybe it begins with magic. Maybe it leads them to Jesus. But why wouldn’t we all walk down that path together?”

The path to acceptance continues at the esteemed Peabody Essex Museum, which just launched an exhibit that includes artifacts from the 1692 trials as well as contemporary responses to that moment in history, aptly titled “The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning and Reclaiming.” It showcases items from Alexander McQueen’s 2007 fashion collection, which was inspired by the designer’s deep dive into his ancestor’s execution, along with portraits of contemporary witches—including HausWitch proprietor Erica Feldmann—taken by noted photographer Frances F. Denny. For the first time in the museum’s history, “we really committed to embracing contemporary witches,” says Peabody Essex associate curator Lydia Gordon. “Salem has become such a beacon and safe haven for folks who practice witchcraft very differently, and it felt very important to accept that.”

History, after all, isn’t static. Yes, it is made up of indisputable facts, some of which, like the 1692 trials or the execution of my ancestor, are undeniably tragic. But the past (to paraphrase Walt Whitman) contains multitudes. And Salem’s undeniably includes the narratives not just of those who were executed here, but also of people like Laurie Cabot, who took a chance and started a revolution, who gave a sense of empowerment to people who needed one. I don’t know anything at all about that woman who bought the $300 wand at Hex, but I personally love the idea of her at home somewhere, channeling her inner strength to break whatever curse, real or imagined, she may be under. Wouldn’t most of us benefit from that kind of spell? At the very least, I think we’d all be better off with a little more magic in our lives.