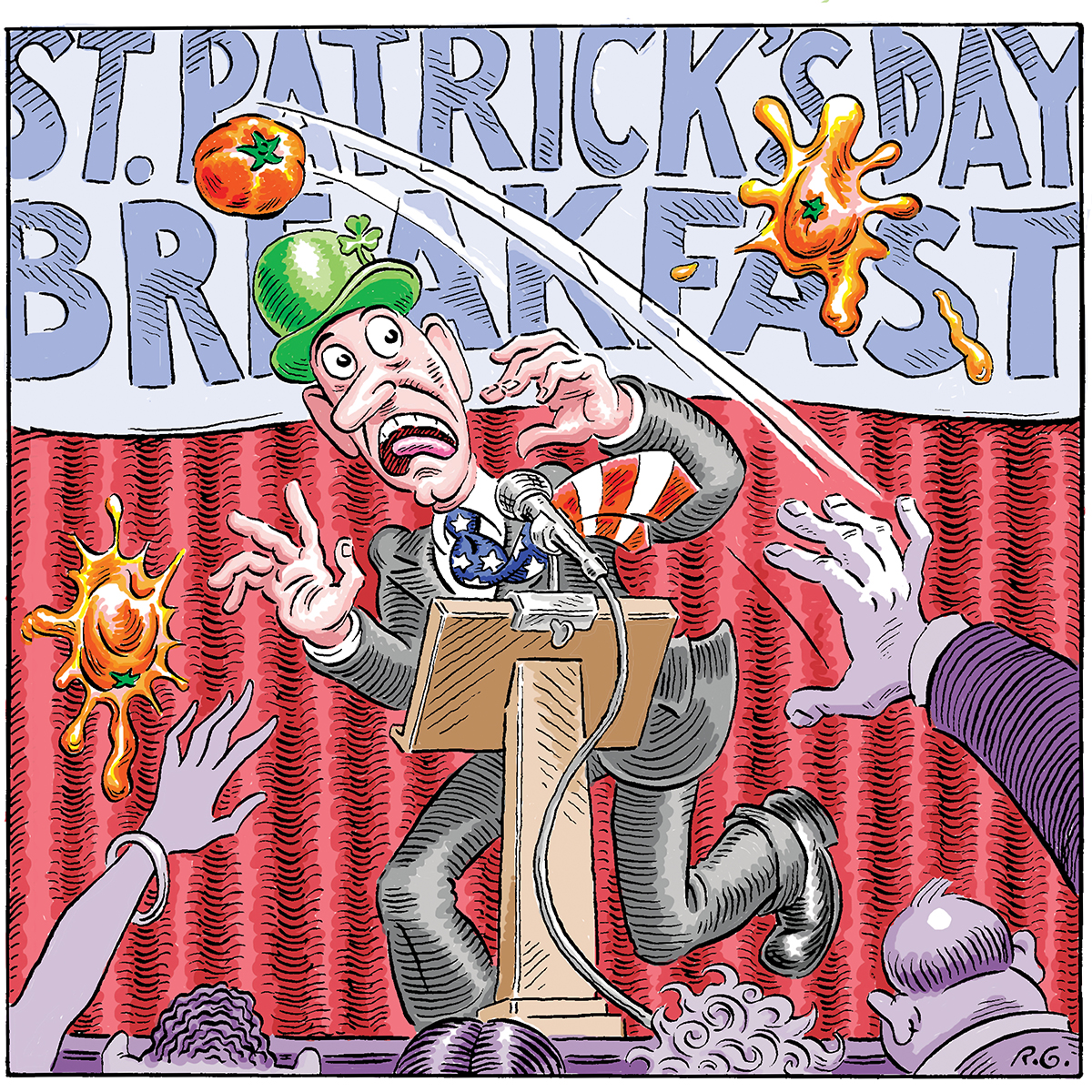

Bombs Awaaaay!

Illustration by Robert Grossman

All eyes were on Maura Hennigan at the 2005 St. Patrick’s Day breakfast.

Days earlier, the 24-year city councilor had announced her intention to challenge Emperor Menino, and her appearance at the often rambunctious annual roast, one of the city’s hallowed political rites of passage, was widely seen as a test of whether she had the balls (as it were) to dislodge Hizzoner—who, incidentally, was seated in the audience. Undaunted, Hennigan took the mic and started in with what was supposed to have been the customary round of pointed jokes. Jokes that, in Hennigan’s case, slapped to the floor one by one, like so many dead fish. “It was like watching a friend go skydiving the first time and realizing they didn’t attach the chute,” recalls City Councilor John Tobin, one of the funniest pols in town, who followed Hennigan onstage that day. “She just came hurtling to the ground. It was just silence. Most of it wasn’t funny, but even the parts that were, people were afraid to laugh because they didn’t want to incur the wrath of the mayor.”

We all know where the story went from there. Menino spent the next eight months pretending he wasn’t being challenged at all, before hitting the switch and effortlessly destroying the dedicated city councilor who’d had the audacity to test his primacy. Hennigan’s flop sweat–soaked stab at comedy neatly prefigured the savage electoral beating she received. And for some observers, that sums up everything that’s wrong with the St. Patrick’s Day breakfast: A female public servant with, to put it lightly, no comedy experience, is compelled to stand before a room full of white guys who have been tacitly warned by Power to let her bomb horribly—which she does, leaving the cognoscenti wondering whether someone who can’t even tell a half-decent joke is capable of running a town like Boston.

For several years now, in fact, there’s been persistent grumbling among the press and the populace that maybe it’s time to let this particular tradition die, that the current crop of pols are at best painfully unfunny, at worst sub-mental, and should no longer be given a platform to embarrass themselves—and, by extension, us—with their antics. Worse, frets the Hub’s significant contingent of humorless ninnies, the event’s inherent Irishness carries the sort of racist and sexist undertones that once plagued the city in its less diverse days, the ones dominated by wiseass Irish guys.

Well, like it or not, it’s that time of year again. The breakfast is back, and with it, that new St. Pat’s tradition: complaining about how lame and anachronistic the spectacle has become. But even though the breakfast has devolved to the point that it’s about as pleasurable as listening to Keith Lockhart read Penthouse Forum aloud onstage for 12 hours (one imagines), the show must go on. It’s a piece of living history for a city that’s come unmoored from a past that, if a lot messier, was at least a lot more interesting than the present. The breakfast marks the one day a year our elected officials attempt to give us something other than their own folly to laugh at, when their backroom maneuverings and doublespeak give way to rare bursts of caustic public truth-telling. Think former Senate president Robert Travaglini joking last year about a new clothing line called “Deval”: “As soon as we put the suit on, it all came apart at the seams.” Or Governor Patrick himself chastising Tom Reilly in 2006 for obnoxiously overplaying the childhood-poverty card on the gubernatorial campaign trail. “By the time of the primary,” Patrick said, “Tom Reilly will be a black man from the South Side of Chicago.” More than all that, though, the breakfast, at its best, can help defuse some of the tensions of a rapidly diversifying political landscape, and help reconcile the dueling Bostons—the old one, and the practically unrecognizable new one. Rather than exacerbating that divide, the breakfast exposes it to the light of day, forcing everyone—observers and the political system itself—to recognize and deal with the fact that the power centers have begun to shift. Indeed, that purpose is encoded in the event’s DNA. The breakfast, after all, grew out of the spirit of political change, with the Irish employing wit, drink, and song to take bites out of the hated Yankee elite. And that truth-to-power function is as necessary today as ever. Kill the breakfast? Nonsense. All it needs is a little updating.

Part of the breakfast’s appeal used to lie in its setting: cramped spots like the old-school Bayside Club or the Ironworkers Hall, where hundreds of political insiders jammed into already packed spaces, poured sweat, and were forced to stumble across tables—and one another—to get at the bathroom. “It had this street-corner charm,” says Southie state Senator Jack Hart, the current host. “It was a glimpse inside a small, crowded room of political chicanery.” That ended after the fire at the Station nightclub in Rhode Island spurred Massachusetts to crack down on overcrowded venues. So Hart moved the breakfast in 2005 to the gleaming, antiseptic new convention center, where attendees no longer had to trip over their neighbors to make it to the urinal, and could be reasonably certain they wouldn’t perish in a huge conflagration. These comforts came at a cost, however. With the added space, the audience soared to more than a thousand, which had the effect of killing off a good deal of the insider feel that had given the event its unique character.

The expanding audience had another consequence, as well: The risk of getting crucified for a politically incorrect joke, of being tarred as an unreconstructed racist/sexist cartoon character from Boston’s Bad Old Days, increased exponentially. This, as you would expect, retards—sorry—cripples—sorry—impedes the likelihood of funny things ever being said, political correctness being the single most effective antidote to laughing. And if that weren’t enough to suck all the funny out of the room, the pols now increasingly rely on prop gags, angling to land their pictures in the papers and on the newscasts. The breakfast is the worse for it: As anyone who’s ever had the misfortune of catching Carrot Top can tell you, prop gags are about as funny as pediatric AIDS, and should be fought with a similar urgency.

To solve some of the most glaring problems, Hart has made a few needed changes recently. With the breakfast having swelled over the years to more than three mind-numbing hours, last year it was limited to two hours—so if it wasn’t nonstop hilarity, neither was it nonstop. This year Hart hopes to trim the size of the audience, and plans to program the event less rigidly to allow for more of the kind of spontaneity unseen since Billy Bulger handed over emcee duties.

That’s a start, but more-drastic steps are needed to whip this thing back into shape. The first is to get the event off TV. The commercial breaks make it too stagy, and the reach of the broadcast heightens the prevailing instinct to play it safe, when, of course, the whole point of the breakfast is to say things about your colleagues that you’re not allowed to say the rest of the year. If some of the jokes touch on race, ethnicity, religion, or sex, so be it. In spite of the frequent cries of a city that often can’t tell the difference between tolerance and pandering, that sort of japery can actually help bring people closer together—it’s a form of sublimation. And that doesn’t mean everyone needs to act the stereotypical Irish pol at this thing, either. The growing ranks of minority officials can take shots at the old white guys, the women can poke fun at the men, and the

whole event can be subverted to meet the needs of modern Boston without throwing old Boston entirely into the garbage. If someone crosses the line, the audience can just boo him/her off the stage, or hurl tomatoes, or lobby the clergy on hand to condemn the offender to an eternal sulfur bath. Or even hiss the clergy. Democracy in action.

Finally, and this may be the most controversial suggestion, bring back Guy Glodis, the redheaded Worcester County sheriff, who was finally banned from the event after a series of brutally inappropriate one-liners that stretched over several years. I’m not endorsing the quality of the man’s humor. But surely there’s space for anyone who stands in front of a room full of Boston politicians, points to the mayor, and says he loved him in Planet of the Apes (to utter silence), or jokes (to mortified groans) about how, as a child, Tom Reilly was so poor he had only one thing to play with. Making room for someone with so little distance between his brain and his mouth is sure to reanimate this corpse, at least in the short term, even if he is ultimately treated to a barrage of flying cabbage and imprecations issued by the five remaining Catholic priests in Boston.

Just imagine: Glodis is at the mic when John Kerry (election year) shows up. Seeing him, Glodis expresses his fervent hope that the junior senator from Massachusetts will at last accomplish what Niki Tsongas couldn’t—namely, losing to Jim Ogonowski. At this point, Kerry emits his halting, laughterlike sound. “Whatta you laughing at, you Jew bastid,” Glodis snaps to scattered boos. Jack Hart walks up with a big hook, removes Glodis, and calls for a song. Someone in the back starts singing “Hava Nagila,” but is silenced by Suffolk County Sheriff Andrea Cabral, who mounts the stage and shakes her head. “Jesus,” she laughs incredulously, “no wonder no one wants you people in power anymore.”