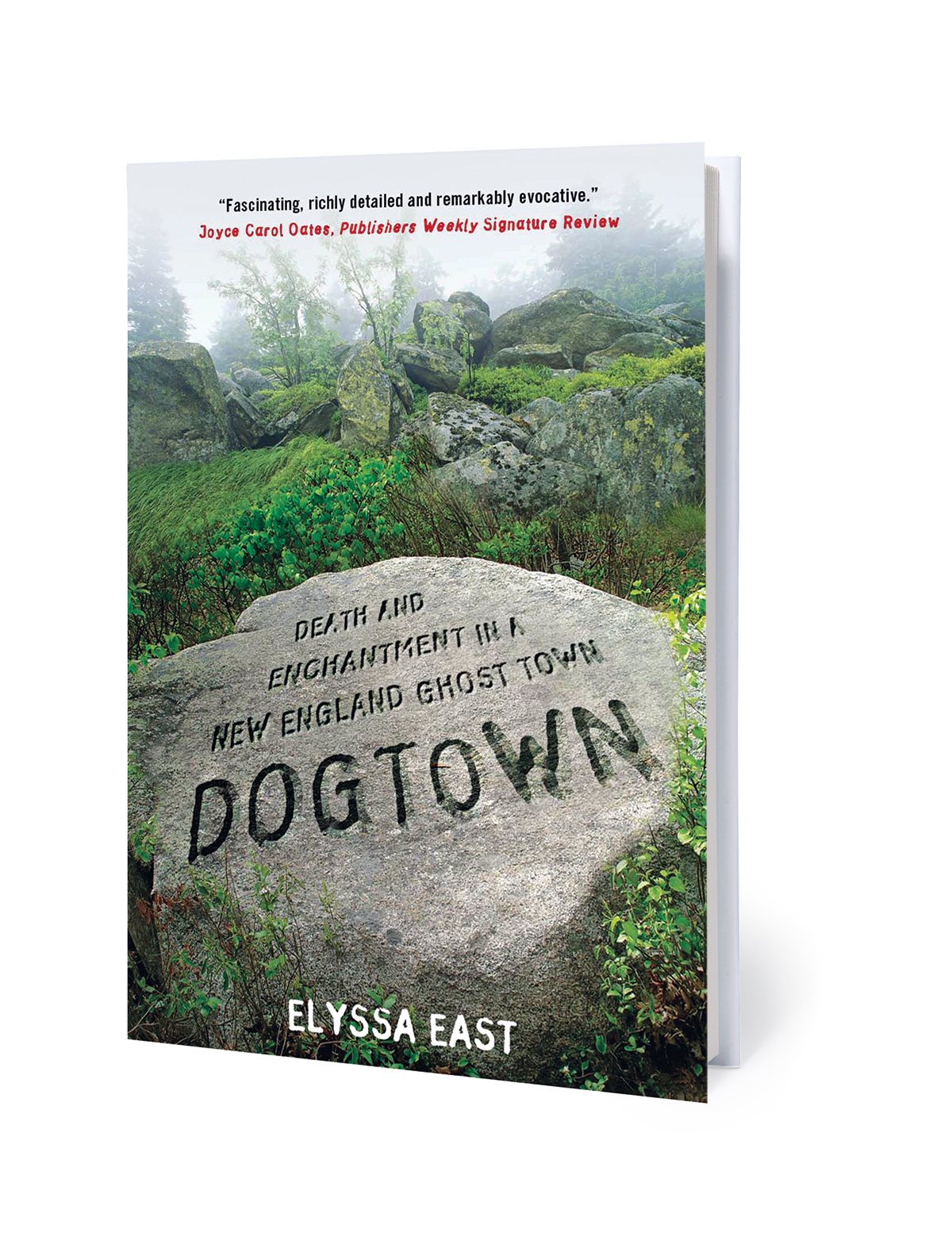

Dogtown Days

Photograph Courtesy Elyssa East

Q. How has this bizarre Cape Ann landscape known as Dogtown existed so close to Gloucester and Boston for so long without being “discovered”?

A. Dogtown was somewhat better known after World War I, thanks to poet Percy MacKaye’s narrative poem Dogtown Common and the early modernist John Sloan’s paintings of the area, but it fell into obscurity during the Great Depression. On Cape Ann, some believe Dogtown’s “dark” reputation has helped keep it lesser known, but [another reason is that] in 1930 Roger Babson, founder of Babson University, donated 1,150 acres of Dogtown land to the city of Gloucester to supply drinking water. A number of people have tried to develop the area—at one point there was an initiative to build an Old Sturbridge Village–style history park there—but those efforts never went through because Dogtown is Gloucester’s principal watershed.

Q. The book is in many ways a meditation on place. What’s unique about Dogtown?

A. Dogtown isn’t a tourist destination, which has helped it remain under-trafficked. Every time I go there, I feel as if I’m living my childhood fantasy of stumbling upon a place that truly feels untouched by time. Cape Ann’s Halibut Point has a similar feeling, but in high season an attendant greets you. The only thing waiting to greet you in Dogtown is the place itself.

Q. Dogtown became a creepy no man’s land after the 1984 murder of a woman named Anne Natti. Do outsiders visit?

A. Dogtown’s dark time is over, thanks to the community’s efforts to clean it up after Natti’s murder. It’s something of a miracle that the area has remained a safe, peaceful wilderness where people can go to escape everyday life, but that happened because enough Cape Ann people wanted the area to stay that way. More people started visiting Dogtown after the publication of Anita Diamant’s novel The Last Days of Dogtown [in 2005], but it isn’t necessarily “on the map.” Dogtown remains a “shadow” [of Gloucester] for introspection and peace because it’s the opposite of the city and the coast and their more vibrant energies.

Q. Is Gloucester actively preserving the land?

A. The city hasn’t embraced the land as the rare cultural and historic resource that it is, but what would embracing Dogtown really mean today and in this economy? No one wants it to become a tourist site—Dogtown trinkets and witchcraft bric-a-brac. Gloucester isn’t the most refined community—it’s a fishing town—but in this respect it has more taste than its neighbors.

Q. Will Dogtown remain unspoiled?

A. This open space is one of the state’s greatest natural and cultural resources, but it’s not widely recognized as such. Many Cape Ann people don’t trust that the city of Gloucester will honor Babson’s bequest. Developers have ways of getting around watershed laws. Part of the Cape Ann interior, or “Greater Dogtown,” as some call it, is already being eaten up by new developments for expensive homes that few native Gloucester people could ever afford. Once a wild place like that is gone, it’s pretty much gone forever.

Q. Since our magazine piece went to print you’ve had readings all over the place, including in Gloucester. What reaction did you get there?

A. Cape Anners have been incredibly receptive to Dogtown and feel that it captures the essence not just of Dogtown, but of the Gloucester community at large. At my Rockport Library reading, John Tuck, who was Anne Phinney Natti’s brother-in-law at the time of her murder, gave me her copy of The Family of Man, the catalog to Edward Steichen’s 1955 Museum of Modern Art photography exhibit that is mentioned in the book. It was an incredibly generous, moving gesture. Inevitably, Dogtown has stirred up painful memories for those who knew and loved Anne Natti. Nonetheless, her friends and family have told me how much they appreciate that the book is not a titillating whodunit, but is also about Dogtown, its nature and people, the very things that attracted Anne to the area.

Q. What seems to interest readers most about the story?

A. Readers seem to fall into two camps. The majority like the story of Dogtown, its quirky characters and strange history, and see the murder as I intended it to be, a narrative that illuminates people’s complicated relationship to the place and its denizens. Readers who have approached the book anticipating a traditional true crime experience are more intrigued by the murder and the murderer, who was a strange, deeply disturbed individual.

Q. We didn’t have enough space to get into Mardsen Hartley in the magazine. Tell us a little about his work and why it appeals to you. Several of his works are at the MFA here in Boston, by the way.

A. When I first saw Hartley’s Dogtown paintings I really didn’t believe they captured an American landscape. They were unusual, unpicturesque, and eerily forlorn. But Hartley’s Dogtown paintings revealed his creative and emotional struggles, which I found undeniably interesting and revealing. New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl wrote, “Hartley’s best art looms so far above the works of such celebrated contemporaries as Georgia O’Keeffe, Charles Demuth. Arthur Dove, and John Marin that it poses the question of how his achievement was even possible.” The answer, as many Hartley biographers and critics have noted, was found in Dogtown. Some of the painterly techniques that Hartley experimented with here became the foundation for his later, greatest work, his landscapes of Maine. But the personal changes Hartley underwent in Dogtown were just as, if not more important, than what he learned as a painter.

Q. What’s your next project?

A. Nearly all of my ideas involve travel to legendary places that are steeped in myth or stories about artists. Right now I am leaning towards a narrative biography of the friendship between some 19th century painters and a novelist, but I’ve only started looking into this idea very recently. Once I have a better idea of the conflict between these figures I’ll know if it’s worth pursuing as a book, a magazine piece, or is one to place on the scrap heap. The challenge in writing narrative nonfiction is that the story is either in the research or it simply doesn’t pan out after closer inspection. Truth is stranger than fiction, but it’s also a lot harder to find.