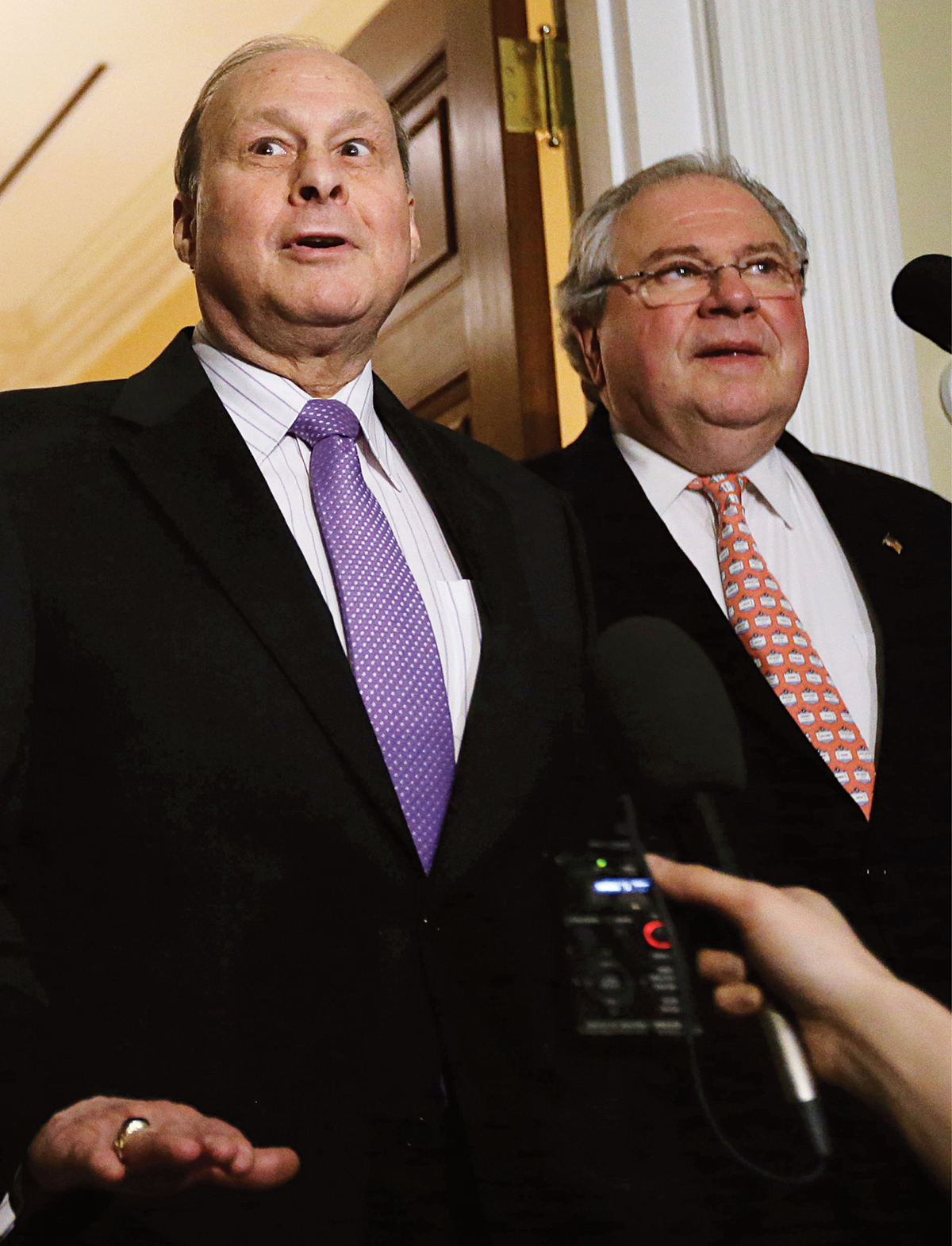

The Odd Couple: Stan Rosenberg and Robert DeLeo

From left, Senate President Stan Rosenberg and House Speaker Robert DeLeo face reporters in January 2015. / Photograph by Steven Senne/AP Images

Last summer, I reported that Robert DeLeo, the speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, had his eyes on a remarkable power grab: eliminating term limits for his own position, allowing him to reign as Speaker for Life. At the time, DeLeo and his top lieutenants denied that such a tactic had ever even occurred to them. Perish the thought.

DeLeo maintained this Sergeant Schultz routine almost until the very minute, in January, that he tossed two reporters out of a caucus room in the State House, closed the doors, and instructed the rank-and-file House Democrats to vote for his new favorite rule. A few brave House members spoke out against the change, and were later punished with unimportant committee assignments. That’s how power works in DeLeo’s House.

Across the hall, the new state Senate President, Stan Rosenberg, has also overseen a few new rule changes, but his have been noticeably different. While DeLeo is amassing power, Rosenberg is happily giving it away, introducing rules to make the Senate more transparent and less centralized under his direct control. Unlike DeLeo’s closed-door caucuses, Rosenberg’s proposals have been debated openly, in public and on videotape, with votes allowed on dozens of suggested changes. These contrasting approaches tell you a lot of what you need to know about the differences between Rosenberg, who just stepped into the Senate’s top spot in January, and DeLeo, who has now extended his House dominance indefinitely. Their leadership styles, however, are just the beginning.

Rosenberg is a gay, policy-wonk liberal from western Massachusetts, and a rootless, self-made success. DeLeo is a lifelong townie, a cigar-smoking regular guy anchored by family, friends, and neighborhood. And as if by purpose, to underline their differences, Rosenberg sat with me for an hourlong interview, while DeLeo assiduously avoids reporters and declined, after a monthlong series of requests, to speak with me, providing no reason at all.

Despite their different methods and paths into the spotlight, the two men—who were born just months apart in Suffolk County—have one important thing in common: Both are schlubs—affable, empathetic, trustworthy, adaptable, smart schlubs—whose natural gifts fit perfectly with the needs of their respective chambers. In the House, where most of the 160 largely anonymous members just want to protect their districts’ interests and avoid controversy, DeLeo centralizes control, takes the heat, and keeps things quiet. In the Senate, where ambitious souls seek to drive policy and get attention, Rosenberg is opening windows, enabling action, and providing assistance.

For the sheep, a shepherd; for the soloists, a conductor.

Of course, the big question is what happens when those two models come into conflict with each other, as they frequently will in the coming years. These two genial men—the ultimate odd couple—have amazingly spent the past 35 years inhabiting the same small world of Massachusetts politics, building relationships, it seems, with almost everyone but each other. They now find themselves on a collision course toward years of high-stakes negotiation, bargaining, and battle—head to head.

Oh, and figuring out when to work with, or against, the new governor in the building, Republican Charlie Baker.

Rosenberg was born in Dorchester in November 1949. Some 10 miles away, DeLeo arrived in East Boston the following March—both among some 7,000 baby boomers birthed in the thriving city during those few months. That coincidence, however, is where their similarities come to a screeching halt.

DeLeo lucked into a stable home life on the Eastie/Winthrop isthmus, while Rosenberg’s childhood was like something out of Dickens: He was taken from his parents and placed in foster care with a couple in Malden. They gave him a roof over his head and dinner each night, but to Rosenberg, it never felt like a family. He has never reconnected with his biological parents or any of his four siblings—not even his twin brother. After high school, he chose to attend the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the only school that offered him financial aid. Alone, he headed west and never looked back.

Historically, most legislative leaders in Massachusetts have lived their entire life not far from the house where they grew up, and stayed closely connected to their hometown. Think of Billy Bulger from South Boston, or Sal DiMasi of the North End. “Nobody who was speaker of the House ever left the ’hood,” says political historian Lawrence DiCara.

DeLeo certainly never did. Not only does he still live in the same house in which he grew up, but pretty much his entire early life transpired in the small patch of land between Route 1A and Massachusetts Bay—a geography that includes Suffolk Downs, where his father, Al, worked for five decades in the Turf Club restaurant. DeLeo went to St. Mary’s Catholic school in East Boston, his grandmother’s house was located just behind his back fence, and many of his father’s nine siblings lived within a mile. Speaking last year to the local Italian-American website Bostoniano, DeLeo joked that his three-family house was “the Italian version of the Kennedy compound.”

When DeLeo did venture briefly out of the ’hood, it was to attend the prestigious Boston Latin School, where he mixed with future all-stars, including former House Speaker Tom Finneran. DeLeo was the youngest in the class, and Boston Latin provided “a very rigorous training ground,” Finneran recalls. Rosenberg has the reputation as a wonkish intellectual, but it was DeLeo, armed with his Boston Latin training, who excelled at school and zipped through Northeastern University before earning a JD at night from Suffolk University Law School. He married young, set up a law practice in Revere, and got increasingly more involved with his community. He joined the Winthrop Elks and the Mixed Sons of Italy before becoming a town meeting member in 1977 and selectman in 1978.

Rosenberg, at that point, had just earned his diploma from UMass; he had to work full time during college and could afford only one or two courses at a time. Along the way he started a sandwich shop called Nosheri—“Most people didn’t know what it was,” he says—expanded it, and eventually sold the business.

As for a life in politics, Rosenberg says his friends pushed him into it. He was working for UMass, at the Arts Extension Service he founded in 1973, when he volunteered on Ted Kennedy’s 1980 presidential campaign. Rosenberg’s first assignment was under then–state Senator John Olver, with whom he coincidentally shared a love for the tuba. Olver ultimately hired Rosenberg, and after six months in the State House, Rosenberg says he knew that he’d found what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. “Stan was very clever at listening to all sides, integrating what he was hearing, and coming up with a road map,” Olver says. And, he adds, Rosenberg could get opposing forces to agree on that plan, each thinking they had achieved what they wanted.

In 1991, when Olver took a seat in the U.S. Congress, Rosenberg captured Olver’s vacant slot in the state Senate. A few months earlier, DeLeo had joined the House of Representatives. That was 24 years ago. They’re both still there, but now they’re in charge.