Ethanol Transport Through Greater Boston Could Be Stopped Dead in its Tracks

Hundreds of residents from Revere to Cambridge are signing a petition to keep a petroleum company from transporting ethanol by train through the heavily populated communities, citing the risk of explosion and “catastrophe.”

But the latest developments on Beacon Hill are finally putting some of their worries to rest as elected officials have pushed language through the Senate that could help stop the potential petroleum shipments.

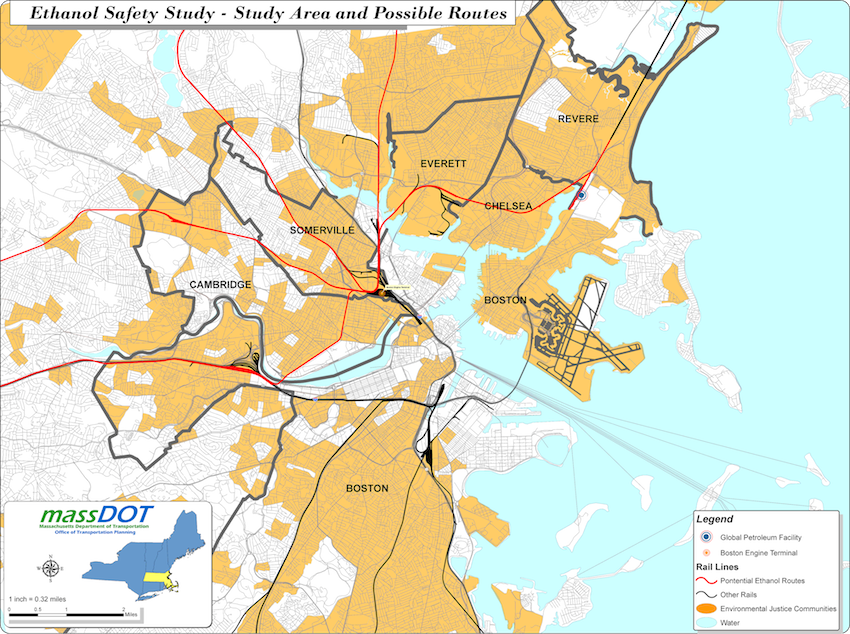

Global Partners LP, which operates a bulk petroleum storage terminal in Revere, where ethanol, an extremely flammable liquid, and other fuels are held before distribution around New England, has been trying to get approval to start transporting ethanol via train, on MBTA-owned tracks. The change in transportation methods would require the trains to travel through nearly 100 cities and towns in the state, including Boston, Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Somerville, and Revere, essentially replacing the company’s current methods of transport by barge near the Chelsea Creek.

Residents like Roseann Bongiovanni, of Chelsea, have expressed concerns about the safety of shipping ethanol unit trains through the various cities, citing the potential for individuals to hijack the vehicles and use the explosive contaminants for a terrorist attack, or the risk of the train vehicle derailing, something that has happened in other states that ship large amounts of the gasoline-like liquid. “We have looked into this quite extensively and have seen a number of serious accidents in the Midwest, where trains have derailed and massive explosions have occurred and evacuations have had to happen,” says Bongiovanni, who’s the associate executive director of the Chelsea Collaborative, a non-profit group that rallies residents to fight certain causes. “This could be catastrophic for our state. When I was watching the marathon bombings, I was like ‘oh my God, some punk could do the same thing, they could know [the trains] are coming through our communities and they could target them’ … it would lead to massive, massive, massive explosions.”

Her fears were magnified recently when two individuals were arrested in Canada for trying to pull off a similar plot.

As communities all around Greater Boston have joined Bongiovanni in the fight against Global’s proposal, Twitter campaigns, like @NoEthanolTrains, have sprouted up as well as petitions from outraged residents following multiple community meetings.

In March, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation released a report commissioned by the legislature to look at the risks involved in the train transport option Global proposed.

Minka vanBeuzekom, a Cambridge City Councilor and one of the members of the task force that issued the report, called Global’s plans “short sighted” for safety reasons. “It’s a terrible idea. These are really dense environments. When the trains go through with this ethanol, in the Midwest, if there is an incident they evacuate maybe 100 people. If you had an incident in Somerville, you could be evacuating 50,000 because you evacuate in a half-mile circle just to be safe,” she says.

In order to change their method of transport from water to train, however, Global needs to make improvements to its facility, including adding the tracks to their headquarters and obtaining a Chapter 91 license from the state. The report issued by MassDOT was the final piece standing in between the company and that license.

But to Bongiovanni’s comfort, Senate leaders added an amendment during budget deliberations on Thursday night that would essentially “nix” the track transport option if it’s pushed through and eventually signed by Governor Deval Patrick. “The Senate voted on the budget that facilities such as this, within half-mile of 4,000 or more residents, and accepting 5,000 or more gallons of ethanol per week, should not receive a Chapter 91 license—so basically they would deny their license,” says Bongiovanni. “I’m super grateful for the work the senate has done, and I’m positive it will get passed. My hope has been for the past year or so that Global would open its eyes and say it isn’t all about the money and withdraw their proposal.”

It may not end there, however. While things look favorable for Bongiovanni and other concerned residents, vanBeuzekom expects it won’t be the last word from Global. “Even if the legislature agrees to add the language so the license isn’t granted, I am sure we won’t hear the end of it. But there is no one I have talked to that thinks it’s a good idea,” she says.