How to Game the College Rankings

Northeastern University executed one of the most dramatic turnarounds in higher education. Its recipe for success? A single-minded focus on just one list.

Photograph by Toan Trinh

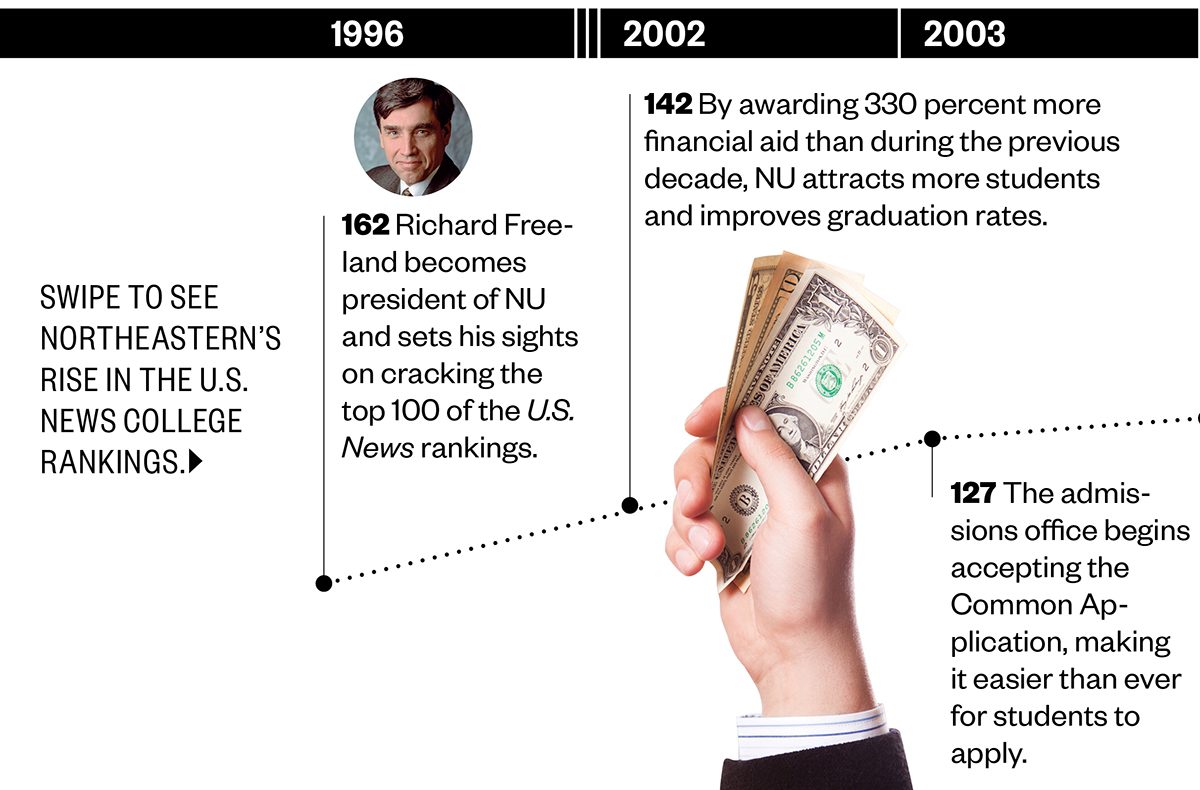

In 1996, Richard Freeland looked across the sea of crumbling parking lots that was Northeastern University and saw an opportunity few others could. As the school’s new president, he had inherited a third-tier, blue-collar, commuter-based university whose defining campus feature was a collection of modest utilitarian buildings south of Huntington Avenue, with a sprinkling of newly planted trees.

The university had been a victim of many things, most notably federal cutbacks—rolled out in the mid-’80s—that had left many colleges scrambling for money to close their budget gaps. These cutbacks, combined with dwindling enrollment, had forced Northeastern’s previous president, Jack Curry, to slash the budget and cut 875 jobs in the early 1990s. When he announced the layoffs to his staff, Curry burst into tears. “To say it was an institution in turmoil would be an understatement,” says a vice provost from that time.

But Freeland, the man who had helped successfully launch UMass Boston over the previous two decades, had a plan. Freeland believed that if Northeastern could justify its increased costs to students and parents, it could be saved. And one gauge consistently determined a college’s value: its position on the U.S. News & World Report “Best Colleges” rankings. Freeland observed how schools ranked highly received increased visibility and prestige, stronger applicants, more alumni giving, and, most important, greater revenue potential. A low rank left a university scrambling for money. This single list, Freeland determined, had the power to make or break a school.

During his tenure, Curry had made improvements at Northeastern, but none of these changes could budge the school’s U.S. News ranking. Working with the mantra “Smaller but better,” Curry reduced class sizes and clamped down on admissions. He also tried to attract students from beyond Boston by creating a more welcoming campus, replacing some of the crumbling blacktops with new buildings, including a library and a recreation center. From the U.S. News perspective, these changes did little to influence the school’s reputation, the most statistically important metric in the ranking system. Curry left the school in 1996 at number 162.

Freeland swept into Northeastern with a brand-new mantra: recalibrate the school to climb up the ranks. “There’s no question that the system invites gaming,” Freeland tells me. “We made a systematic effort to influence [the outcome].” He directed university researchers to break the U.S. News code and replicate its formulas. He spoke about the rankings all the time—in hallways and at board meetings, illustrating his points with charts. He spent his days trying to figure out how to get the biggest bump up the charts for his buck. He worked the goal into the school’s strategic plan. “We had to get into the top 100,” Freeland says. “That was a life-or-death matter for Northeastern.”

Founded in the 1930s and 1940s by David Lawrence as two separate newsweeklies, U.S. News and World Report merged in 1948, but it wasn’t until 1983 that the publication printed its first cover story ranking America’s top 50 colleges. The issue happened to coincide with a sudden robust interest in higher education among the general population: Between 1970 and 1983, college enrollment increased 47 percent. What had once been considered a privilege for the wealthy or brilliant few was increasingly becoming the entry fee to the middle class. For the first time, a college degree was considered necessary, but how to choose among the thousands of institutions conferring degrees? Thus followed a new demand for unbiased, quantitative information—just as Consumer Reports rated washing machines, college rankings would serve as a first-time buyer’s guide to higher ed.

Along with the U.S. News list, the New York Times had just released Edward Fiske’s first Guide to Colleges, and in 1984, the College Board began regularly selling SAT prep books. But none had the authority of U.S. News. Billionaire publisher Mort Zuckerman seized the moment and purchased the magazine, along with its rankings franchise, in 1984.

In the offices of U.S. News & World Report in Washington, DC, Robert Morse has labored for decades, crunching numbers for college rankings (this year, they’ll be released on September 9). He spends his days staring at two computer monitors, analyzing the data that schools submitted over the summer. For a man whose life’s work triggers a yearly cage match among universities, Morse is far from intimidating. He slouches and shuffles, letting the plastic dry-cleaner clips on his shirt go unnoticed. Yet as chief data strategist and developer of U.S. News’s secret rankings sauce, Morse has helped the magazine become one of the most feared and influential voices in the world of higher education.

When the U.S. News editors first devised a formula that declared, with statistical accuracy, which school was on top, they quantified something previously thought to be intangible. For generations, colleges and universities had generally relied on a mysterious brew of prestige and reputation. Suddenly, legacies and tradition—qualities that had taken decades, and sometimes centuries, for schools to cultivate—were less important than cold, hard data. Schools that once relied on children of alumni and word of mouth were exposed by their own stats, including graduation and retention rates, admissions data (acceptance rate, average SAT score), academics (class size, number of full-time faculty), and reputation (peer reviews). Needless to say, U.S. News’s college rankings landed on the world of higher education with a thud.

With their authoritative tone, the rankings also introduced new possibilities. Before they appeared, it was doubtful that NU could ever rub shoulders with Boston College or Harvard. But now, with a codified system out there, nearly everything was reduced to numbers. And those numbers could be beat. “They give you a playing field on which you can play,” Freeland says of the rankings. They give schools “a way to compete.”

From the start, schools have argued that the rankings are subjective. Defenders of the rankings maintain that the system exposes students to more schools and helps the consumer compare products. Regardless, students, graduate schools, and employers have embraced the list, giving it unprecedented power. An unintended result, however, is that schools need to spend more to stay competitive in the categories that U.S. News considers important. Universities may be in the business of education, but it’s a competitive business in which all compete for students and revenue. With an arms race to the top, higher education has soared out of reach for an increasing number of Americans. NU tuition alone in 1989 was $9,500; today it’s $42,534.

“You can love us or hate us, but we’re not going away,” says U.S. News editor Brian Kelly. “University officials realized we’re much more valuable to them than not.” He deflects criticism, saying, “It’s not up to us to solve problems. We’re just putting data out there.” He does, however, admit that the rankings system can be gamed.

Former Northeastern president Richard Freeland, the mastermind behind the school’s meteoric rise. / Portrait by Scott M. Lacey

For those at Northeastern, breaking into the U.S. News top 100 was like landing a man on the moon, but Freeland was determined to try. Reverse-engineering the formulas took months; perfecting them took years. “We could say, ‘Well, if we could move our graduation rates by X, this is how it would affect our standing,’” Freeland says. “It was very mathematical and very conscious and every year we would sit around and say, ‘Okay, well here’s where we are, here’s where we think we might be able to do next year, where will that place us?’”

Figuring out how much Northeastern needed to adjust was one thing; actually doing it was another. Point by point, senior staff members tackled different criteria, always with an eye to U.S. News’s methodology. Freeland added faculty, for instance, to reduce class size. “We did play other kinds of games,” he says. “You get credit for the number of classes you have under 20 [students], so we lowered our caps on a lot of our classes to 19 just to make sure.” From 1996 to the 2003 edition (released in 2002), Northeastern rose 20 spots. (The title of each U.S. News “Best Colleges” edition actually refers to the upcoming year.)

Admissions stats also played a big role in the rankings formula. In 2003, ranked at 127, Northeastern began accepting the online Common Application, making it easier for students to apply. The more applications NU could drum up, the more students they could turn away, thus making the school appear more selective. A year later, NU ranked 120. Since studies showed that students who lived on campus were more likely to stay enrolled, the school oversaw the construction of dormitories like those in West Village—a $1 billion, seven-building complex—to improve retention and graduation rates. NU was lucky in this regard—not every urban school in the country had vast land, in the form of decrepit parking lots, on which to build a new, attractive campus.

There was one thing, however, that U.S. News weighted heavily that could not be fixed with numbers or formulas: the peer assessment. This would require some old-fashioned glad-handing. Freeland guessed that if there were 100 or so universities ahead of NU and if three people at each school were filling out the assessments, he and his team would have to influence some 300 people. “We figured, ‘That’s a manageable number, so we’re just gonna try to get to every one of them,’” Freeland says. “Every trip I took, every city I went to, every conference I went to, I made a point of making contact with any president who was in that national ranking.” Meanwhile, he put less effort into assessing other schools. “I did it based on what was in my head,” he says. “It would have been much more honest just to not fill it out.”

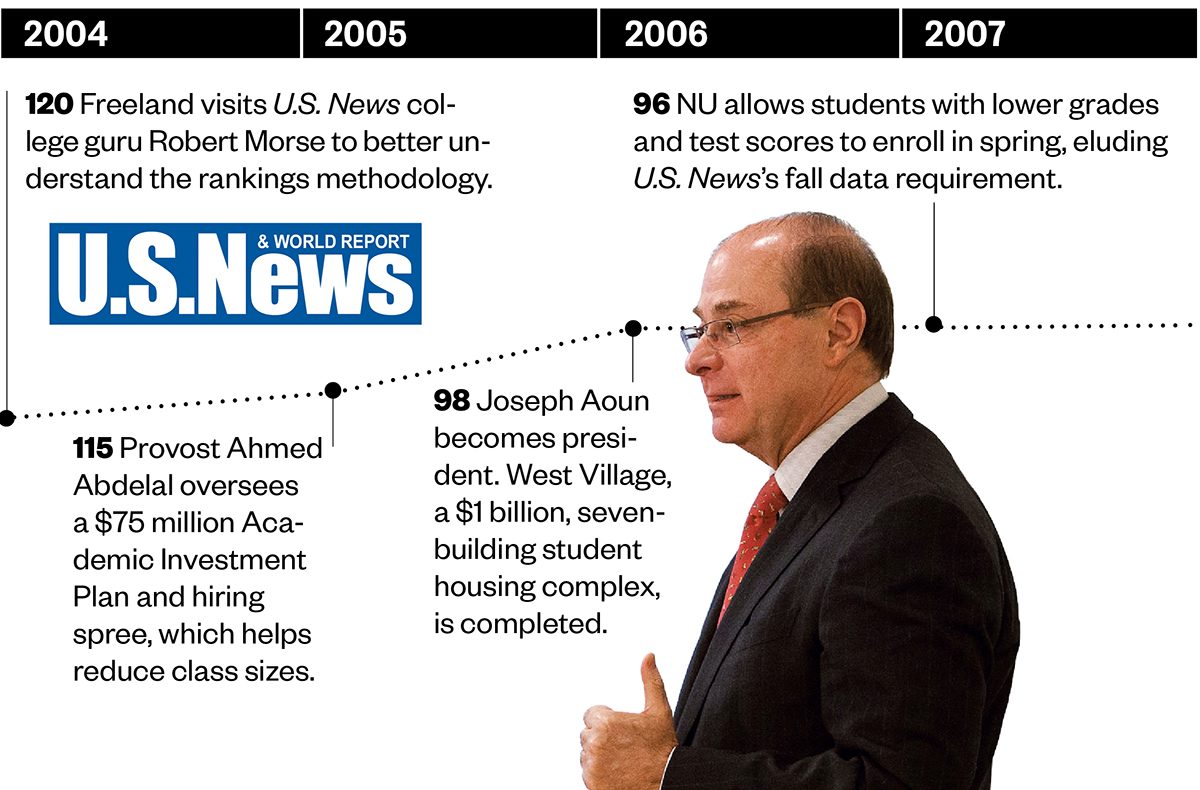

With unwavering dedication to the rankings, Freeland jockeyed his school up 42 spots to 120 over eight years. Though impressive, getting to the elusive top 100 remained Freeland’s ultimate goal, but he had “gamed” the system as far as he could on his own. To break into the top 100, he’d need more intel on the news magazine’s methodology. He would also need U.S. News’s complicity. “We were trying to move the needle,” Freeland says, “and we felt there were a couple of ways in which the formula was not fair to Northeastern.”

And so it was in 2004 when Freeland, a 63-year-old with bushy gray eyebrows and slightly unkempt hair, stepped out of a taxi near the waterfront in Washington, DC’s fashionable Georgetown neighborhood. With his head down, his lips tightly pursed, he marched into the red-brick offices of U.S. News, determined to make the rankings wizard, data guru Robert Morse, his accomplice.

Meanwhile, other schools that couldn’t successfully game the system were trying to cheat their way to the top.

In 2008, Baylor University told newly admitted students that they’d receive a $300 campus-bookstore credit if they retook their SATs, and $1,000 a year in student aid if the scores improved by more than 50 points. In 2009, an administrator at Clemson University, whose president shared Freeland’s rankings fixation, admitted the school misrepresented financial information and purposefully rated institutions low on the peer assessments.

In 2011, Iona College officials admitted to misreporting acceptance rates, SAT scores, graduation rates, and alumni donation amounts over the course of a decade. In 2012, Claremont McKenna College copped to misreporting SAT scores for several years. Also in 2012, George Washington University admitted to inflating the percentage of students who graduated at the top of their high school classes, and Emory University said it had misreported high school GPAs for four years and SAT scores for nearly a dozen years.

Despite those instances, Brian Kelly, of U.S. News, says that misreporting is rare. U.S. News crosschecks some data with government records and other published sources, but that won’t help if a school is lying about data across the board. When misreporting does occur, U.S. News says it might temporarily “un-rank” a school if the bad data affects its standing. “Ninety-nine point nine percent of the schools are treating this seriously and reporting with integrity,” Kelly insists.

Cases of misreporting have only strengthened the anti-rankings movement, which has been around for decades. Lloyd Thacker, who worked in college admissions and founded the Education Conservancy, in Portland, Oregon, is one of U.S. News’s fiercest critics. He says research shows that the rankings distort the way students, parents, high schools, and colleges pursue and perceive education. “Have rankings contributed to anything beneficial in education?” he asks. “There’s no evidence. There’s lots of evidence to the contrary.”

Because schools reap benefits from a high spot on U.S. News’s list, he says, it makes sense for them to continue to throw money at the metrics. From the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, for instance, to lure students with high GPAs and SAT scores, private four-year schools increased spending on merit-based aid from $1.6 billion to $4.6 billion. Studies show that for every 10 merit-based scholarships, there are four fewer need-based scholarships. That’s because schools often base merit on test scores, and students from lower-income families generally don’t test as well, largely because they spend less on tutors and SAT prep. Tuitions rise to help universities keep pace, further reducing middle-class access to a top-flight education.

Freeland landed in Morse’s U.S. News office that day in 2004 to discuss, among other things, how the publication handled students enrolled in NU’s co-op program. Long the cornerstone of the university’s curriculum, the program let students take breaks from their studies in order to gain professional experience in their chosen fields for months at a time. NU maintained that this jobs program was critical to its graduates’ success—it was one of the school’s greatest strengths. Unfortunately, Morse counted co-op students in enrollment data, making it look like more students were using university resources than actually were. This brought down the U.S. News “financial resources” criterion, thereby hurting NU’s rank. From 2002 to 2003, that was the only metric in which NU actually did worse.

Though Morse initially wouldn’t go along with Freeland’s request to change the magazine’s methodology to address Northeastern’s co-op, Freeland emerged from the U.S. News office more confident than ever that NU could crack the top 100. Morse had agreed with Freeland’s overall reasoning and helped him better understand the criteria. It was just enough insight for Freeland to work with.

The following year, NU’s ranking advanced to 115. With its rankings that fall, U.S. News published a three-page article praising Northeastern’s co-op program. The publication wouldn’t reveal whether it changed its policy, but Northeastern no longer includes co-op students in its reporting. At that point, Freeland says, “We discovered that we could actually start to move pretty quickly. The more we discovered that, the more we focused on it.”

Not everyone, however, was onboard with the rankings push. “I think one of my tasks actually at Northeastern was to persuade the faculty that this was a good and reasonable vision,” says Ahmed Abdelal, provost at the time. But, he says, “I’m not going to claim that we converted every faculty member.” One former administrator describes NU’s former president as controlling and single-minded. “I think Freeland was much more focused on the ratings and not necessarily on what it took to improve the quality of the institution,” the former administrator says. “He was going to do whatever it took to increase the ratings.”

The day after Freeland retired in August 2006, he was vacationing on Martha’s Vineyard when he heard the news: The U.S. News rankings were out, and Northeastern had broken through the top 100, all the way to number 98. In his decade as president, Freeland had lifted the school up more than 60 spots, prompting the Boston Business Journal to later call NU’s rise “one of the most dramatic since U.S. News began ranking schools.” Before Freeland left, the trustees had voted again on an amount for his retirement supplement, awarding him around $2 million to acknowledge his success. Years later, the state would name him commissioner of higher education.

Leery of being misunderstood, Freeland tells me, “It may have seemed a little foolish at the time or a little shallow at the time, but the proof of the pudding is in the eating.”

From his office, current Northeastern president Joseph Aoun looks out over the construction of a new residence hall—the school’s 12th since 1996—situated behind the YMCA where NU began more than a century ago. Wearing a suit, a pink shirt, and a salmon-colored tie, he sits cross-legged in a white leather chair and holds his eyeglasses between his thumb and index finger. When he requests water from his secretary, it arrives in a stemmed glass with two lemon slices. This is a man who is clearly used to winning, and takes pleasure in the spoils.

When Freeland retired in 2006, NU trustees saw in Aoun the right man to keep the rankings machine rolling. Aoun had been dean of the College of Letters, Arts and Sciences at the University of Southern California; during his tenure as dean, the school rose eight spots between 2000 and 2006, breaking into the top 30. Aoun says that NU’s trustees were targeting candidates from large private schools that had “moved up in the trajectory.”

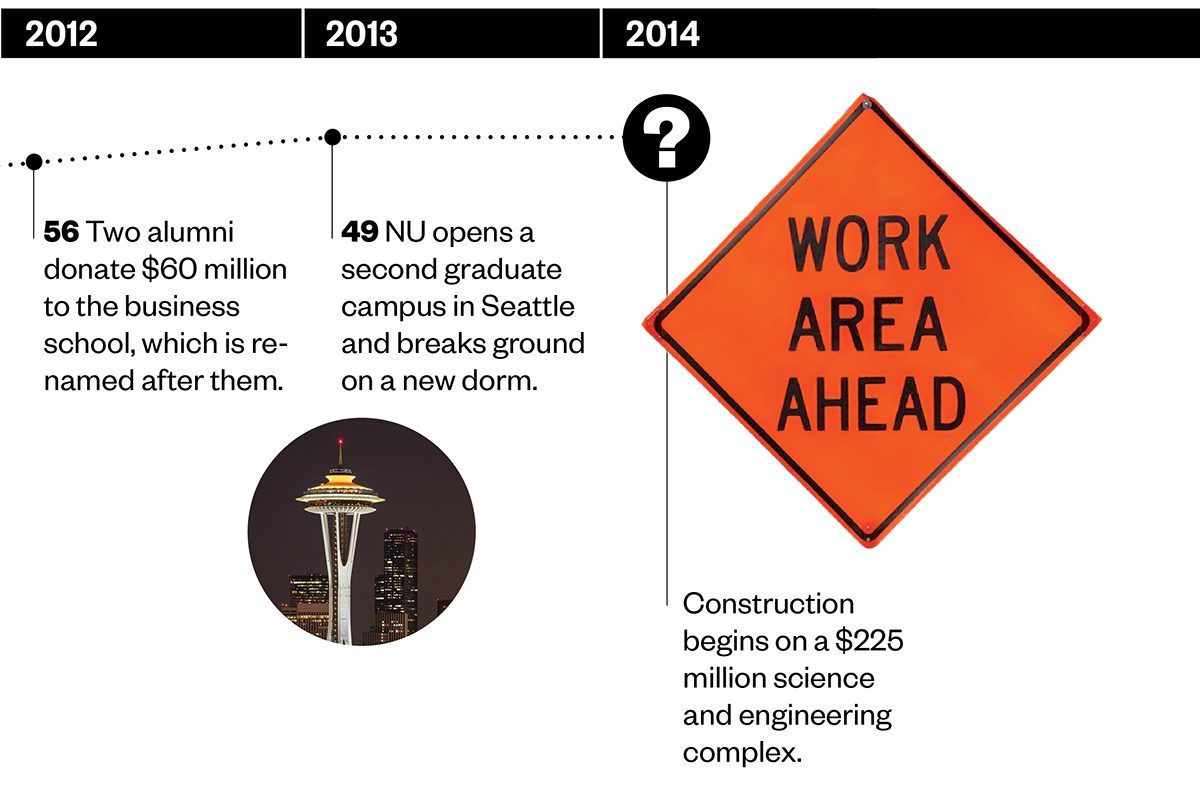

In many ways, Aoun tries to distance himself from Freeland. He resists talking about the school’s meteoric rise over 17 years—from 162 to 49 in 2013—and plays down the rankings, brushing them aside like an embarrassment or a youthful mistake. “The focus on the ranking is not a strategy, for a simple reason,” he says. “You have thousands of rankings. So you will lose sleep if you start chasing all of them.” While it’s true that U.S. News no longer appears in the university’s strategic plan, it does appear in NU’s portrayal of itself: The school has no qualms using its high ranking in recruiting materials and publicity videos. Yet multiple Northeastern administrators expressed concern over this article’s focus on the rankings. One vice president telephoned Boston’s editors in a panic.

Despite Aoun’s carefully crafted image, the school’s actions undercut his words, as gaming U.S. News is now clearly part of the university’s DNA. And Aoun is a willing participant. “He may not admit to it, but that’s definitely what’s going on,” says Bob Lowndes, who is retiring as vice provost for global relations. Ahmed Abdelal, provost under both Freeland and Aoun, says the two presidents have shared “the same goal: further advancement in national ranking.”

Under Aoun, in an apparent effort to score rankings points by lowering the percentage of accepted students, NU’s admissions department received a mandate: Increase applications at home and abroad. Northeastern’s new science and engineering complex, colorful Adirondack chairs throughout campus, and star faculty members like Michael Dukakis are all intended to advance reputation and lure top students. “They poured a ton of money into admission recruiting,” says a former NU admissions officer. “We had amazing amounts of latitude to travel overseas. We worked really hard, and we traveled like crazy.”

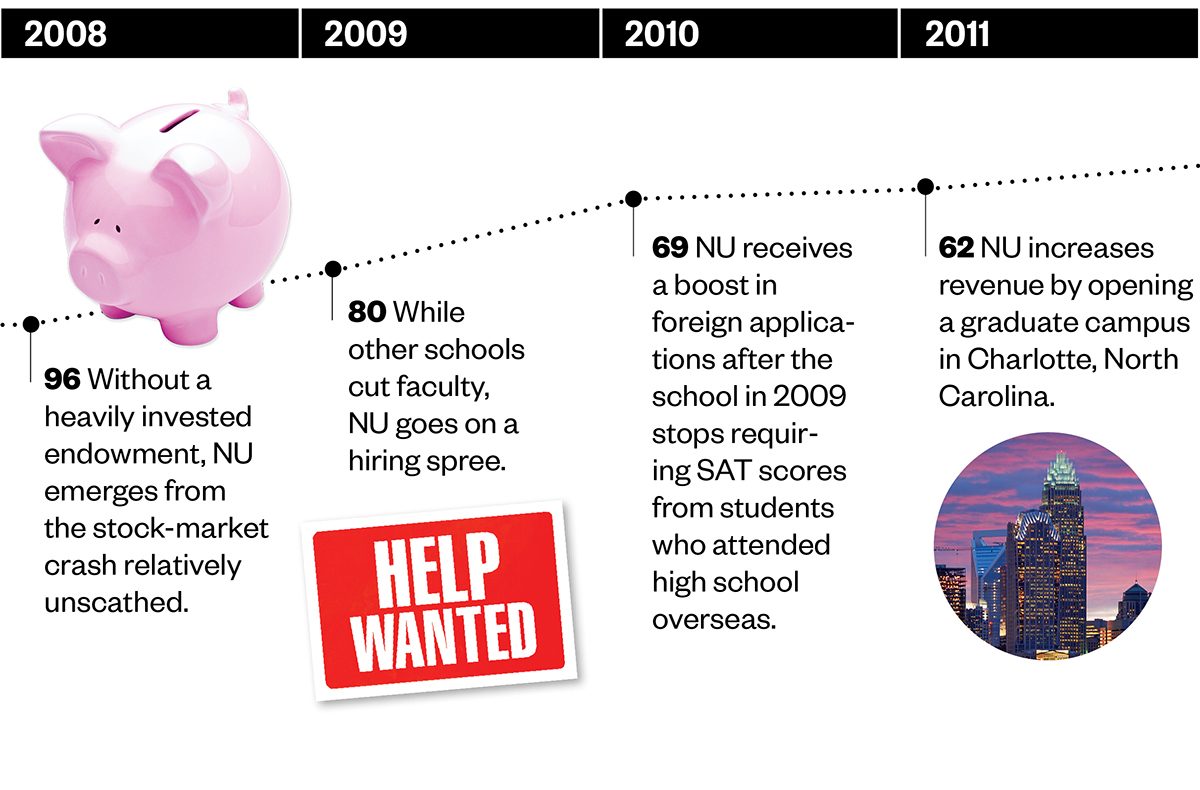

There were other tricks, as well. In 2009, NU stopped requiring SAT scores from students attending international high schools. By removing a barrier to foreign students, who typically score lower if they take the SATs at all, NU boosted its application numbers without jeopardizing its overall testing average. Those foreign students, ineligible for federal aid, also tend to pay full freight. Since 2006, the percentage of international undergraduates has jumped from just under 5 to nearly 17. In the 2012 to 2013 school year, NU had the most international students of any university in New England, and the 10th most in the country.

Aoun also began using spring enrollment to his advantage. In 2007 the school introduced N.U.in, a program that invites students with lower grades and SAT scores to spend their first semester abroad and begin their on-campus experience in the spring. U.S. News does not collect data for spring entrants, so those students’ lower grades and scores are excluded from the rankings. Editor Brian Kelly explains that U.S. News doesn’t require spring data because the federal government doesn’t either, but he concedes, “It’s possible that is a gaming window.”

Aoun’s tactics seem to have worked. Last year, Northeastern received its highest number of applications, almost 50,000 for 2,800 spots. That’s nearly five times more than in 1990. Enrolled students were more qualified than ever before, with average SAT scores up 22 points from the previous year. “They’re at the level of Ivy League schools,” says Henry Nasella, NU’s chairman of the board of trustees. “People are always talking about the value of their degree,” says last year’s student-body president, Nick Naraghi. “Not only am I getting what I was thinking I would get, I’m getting much more.”

Serving as the president of a top-50 school has its perks. Aoun lives in a 14-room townhouse overlooking Boston Common that the school purchased his first year, now worth $8.9 million. A chauffeur drives him to campus. Aoun’s salary increases each year, and in 2011, he was the second-highest-paid college president in the country, at $3.1 million, though that included a $2 million retirement supplement. (Harvard’s president, Drew Gilpin Faust, came in 54th that year, with total compensation just under $900,000.) In addition to Aoun, seven Northeastern employees made over half a million dollars that year.

Northeastern has essentially created a blueprint for any school that can stomach following it, but gaming the U.S. News rankings has its costs: According to a study published this year by Research in Higher Education, a mid-30 school like the University of Rochester would have to spend an extra $112 million on faculty salary and student resources alone to rise a total of two spots. To feed the beast, Aoun has tapped several new streams of revenue, including satellite graduate campuses in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Seattle, as well as online education. Nasella calls them “very important” and claims they are “very profitable” for the school.

“There’s no rankings problem that money can’t solve,” says Michael Bastedo, director of the Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education. Actually, there may be one—a ranking system with enough credibility to overshadow all others has appeared on the horizon, and this one will be much tougher to game. Concerned about the skyrocketing costs of a college education, the White House is launching a federal rating system that, unlike U.S. News’s, will focus less on student inputs (e.g., SAT scores) and more on the resultant value of a degree—weighing a school’s tuition costs, graduation rates, and postgraduate salaries. The government hopes to implement the system this fall. Don’t expect to find NU at the top: In Money magazine’s 2014 “Best Colleges for Your Money,” which uses a similar methodology, Northeastern landed at the bottom of the third quartile, at number 433.

By the Numbers

NORTHEASTERN’S RISE IN THE U.S. NEWS COLLEGE RANKINGS

Check out all of our Best Schools 2014 coverage.