Can Catholic Schools Be Saved?

Financial woes, fewer students, trouble recruiting teachers, and a rash of high-profile school closures. Does this spell the end of an iconic educational institution in Boston, or is there still time for a Hail Mary?

Photo illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Source image generated by AI

On the morning of May 3, 2023, a couple hundred uniformed students filed inside the Cambridge Matignon School’s wood-paneled auditorium and quickly took their seats. All around the school there were reminders of its long and storied 75-year history— from the banners and trophies that marked its time as a 1980s hockey powerhouse to the midcentury details that were hallmarks of the Cardinal Cushing–era architecture. And now, this assembly would make history, too. The head of school took the floor before the student body and announced that today would be one of the last gatherings at the Catholic high school. Matignon was closing its doors—for good—at the end of the school year.

By then, most students and teachers knew this announcement was coming. The previous afternoon, just after the final school bell rang and kids flooded out of the school’s hallways into the rainy, foggy Cambridge afternoon, Matignon administrators had ushered faculty members into that same auditorium and notified them that they would soon be out of work. Moments later, the school’s board blasted out an email titled “A Somber Announcement from The Cambridge Matignon School” to students, parents, and alumni of what was the last remaining Catholic high school in Cambridge. “We were blindsided,” says former class president Alexiah Lingley, then a 17-year-old junior. “We had so many plans for next year.”

For their part, parents also felt abandoned given how the school handled the situation. “We never got a real answer,” says Jenn Silva-Matos, a parent and alum. “It was all very generic and ‘good luck!’” Several students noted that they never saw the head of school on campus again that year.

As upsetting as Matignon’s demise was, it is just the latest in a string of high-profile school closures across the Archdiocese of Boston over the past year. The first, Saint Joseph Prep Boston in Brighton, announced in February 2023 that its doors were shuttering on account of “insurmountable financial pressures.” That March, Mount Alvernia High School in Newton surprised its community by announcing it was closing and the order-owned property would be sold.

For nearly two centuries, Catholic schools have been a fixture in the Boston area, long intertwined with the evolution of neighborhoods and family histories. They have created and sustained generations of Catholics and provided a path toward upward mobility for many immigrants and working-class families. Whether in the realm of politics or business, countless leaders and successful Bostonians are products of a Boston Catholic school education.

Today, as frustration with Boston Public Schools mounts, private school tuition soars, and coveted seats in the city’s public exam schools become even tougher to secure, Catholic schools remain an important alternative for more than 30,000 students, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, and an integral component of the city’s educational offerings. But after witnessing decades of declining enrollment, scandals, and the sale of school and church properties, families and outside observers are left wondering whether this latest cluster of closures is another one-off—or whether the era of Catholic school education in Boston is coming to an end. If the latter is true, it would represent a seismic shift in the educational landscape, one that could change Boston forever.

Mount Alvernia, closed in 2023. / Photo by John Phelan

Walking down Dorchester’s Columbia Road in the 1960s, it would’ve been tough to miss Saint Margaret School amid the surrounding neighborhood triple-deckers. Neat as a pin, the 1909 brick schoolhouse existed for a missionary purpose: to provide an education to neighborhood children that would leave them spiritually and intellectually better off than when they started. Inside, the sternly habited Sisters of Charity-Halifax led plaid-uniformed, predominantly Irish-Catholic children down its long hallways and through its stained-glass doorways.

At the time, St. Margaret’s and many other schools in the Archdiocese of Boston served as hubs of burgeoning Catholic communities; you were never more than a stone’s throw away from one, with more than eight Catholic schools in Dorchester alone. “Your whole life was based around St. Margaret’s,” recalls former Mayor Marty Walsh, a Dorchester native who attended the school. “We had nearly a hundred altar boys and a strong Catholic youth organization (CYO)—even the kids that went to public school were part of it. Many of us were first-generation from immigrant families—Irish, Italian, Polish, depending on the neighborhood.”

The story of Boston’s Catholic schools, which began popping up in the early 19th century, encapsulates the often-interlaced destinies of immigrant groups and Catholics throughout the city’s history. The educational model got off to a slow start, given that anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiments often went hand-in-hand. Boosted by waves of Italian and Irish immigrant families in the late 19th and early 20th century, though, the schools began growing in number, and by the middle of the century, there were more than 150 parochial schools and nearly 100 Catholic high schools, which together had a major influence on Boston’s cultural identity. The schools developed strong academic and athletic reputations and became known for churning out successful alums, including educators and politicians, so much so that local parents, Catholic or not, eventually considered them an avenue for getting their kids into top-tier universities.

By the 1980s, though, the numbers of priests and nuns began to dwindle rapidly, and without the free labor of religious orders, Catholic schools raised tuition to fund operations, putting them out of reach for some families. At the same time, many of the early Irish and Italian families started moving out of Boston neighborhoods and into the suburbs, and church demographics shifted toward Portuguese, Haitian, Brazilian, Vietnamese, and Hispanic families, many of whom—like recently arrived immigrant groups before them—couldn’t necessarily afford to pay tuition at the schools.

Then came the earthquake felt ’round the world. In the wake of the Archdiocese of Boston’s child-sex-abuse scandal that broke in 2002, disillusioned and frightened families abandoned the Catholic Church. Faced with bankruptcy and roughly $100 million in payments to victims dealing with years of trauma, the church closed many schools and sold their high-value properties to stay afloat.

It wasn’t enough. In 2004, the archdiocese was forced to embark on a widespread reorganization to save as many schools and parishes as possible, which included further closures, parish mergers, and the creation of regional urban academies governed by a board rather than a pastor. St. Margaret’s closed that same year. “It hurt a lot of people because you felt like you lost the identity of the parish,” Walsh recalls. “But there’s no way all these schools could have survived.”

In the end, it was the organized efforts and fundraising by some of Boston’s most successful entrepreneurs and philanthropists, including finance whiz Peter Lynch and advertising legend Jack Connors—both of whom credited Catholic education with giving them a leg up in life—that helped keep many remaining schools open and formed new sustainable models for others. Today, there are 93 Catholic schools across 49 cities and towns in the Archdiocese of Boston. That number includes early-education programs as well as elementary and secondary schools in a variety of formats, from completely independent private high schools run by religious orders to regional schools run by independent boards to local parochial elementary schools run under the discretion of parishes. Some of these schools fall under the jurisdiction of the archdiocese, which operates the Catholic Schools Office (with a superintendent tasked with managing the schools), though the relationship between schools and the office is not always clear.

Unlike their public counterparts, which operate under the guidelines of a district system, the hodgepodge, ad hoc makeup of the archdiocese’s so-called school system continues to breed its own confusion and controversy. Even Auxiliary Bishop of Boston Mark O’Connell, who as vicar general and moderator of the curia is the archdiocese’s highest-ranking official other than the cardinal, has described the system as a little bit “weird.” “Each school has different curriculums, atmospheres, and politics, from progressive to conservative. That diversity is part of the beauty of it,” he says. It also presents challenges for anyone—parent, teacher, or superintendent—trying to navigate it.

Even if it can feel disorganized at times, the benefits of this alternative educational model cannot be overlooked. Catholic schools have consistently boasted higher student test scores, graduation rates, and college enrollment than their private and public counterparts. What’s more, they have done it while spending far less than what public schools in the state spend per pupil. “They’ve figured out how to do a lot with limited resources,” says Rachel Weinstein, chief collaboration officer at Boston Compact, a community of educators focused on helping Boston schools.

This achievement isn’t just important for the families whose kids attend these schools, but for everyone in Boston. After all, these schools have achieved success largely without drawing from state or municipal coffers, saving taxpayers millions while easing pressure on Boston’s strained public school system and giving some parents a reason to live in Boston rather than flee to the suburbs to raise a family. In other words, if there are no more Catholic schools, we’ll all feel it.

Bishop Mark O’Connell is tasked with choosing the next superintendent of Catholic schools, who will lead a school system at a crossroads. / Photo by Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

On a Wednesday evening earlier this year, a who’s who of 130 school leaders and high-powered supporters quietly convened to discuss the fate of Catholic schools in the Archdiocese of Boston. The meeting was led by two fresh-faced young women, Katie Frett, a Teach for America alum and former charter school administrator, and Annie Smith, a former Catholic Schools Office employee. They cut a stark contrast to the sea of blazers and Roman collars filling the room at Boston College High School, a boys-only Jesuit stronghold with an ever-expanding campus. (The crown jewel in the Catholic education universe, the school recently received a $49 million gift, which the school says is the largest ever for a New England Catholic secondary school.)

Convinced that it was time to stop sweeping troubles at Catholic schools under the rug, as had long been the case, these women had recently launched the Catholic Schools Support Network (CSSN) in the wake of the recent closures. The organization’s goal is to collect and analyze data from institutions to help pinpoint weaknesses before schools are so far gone they are forced to close, and to foster much-needed collaboration between schools, instead of an atmosphere of competition. On that January night, they were getting ready to present their findings on how the archdiocese’s schools can survive into the future.

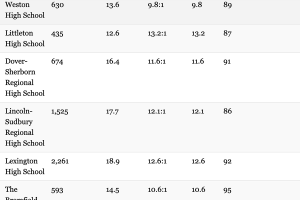

So how, exactly, does it work? The network, which launched with a 29-school pilot program, asks educational institutions to open up their books and share their data with the network for analysis. The data collection doesn’t just help individual schools craft targeted plans for improving specific weaknesses, such as low enrollment or test scores. It helps schools collaborate and learn from one another about what works and what doesn’t. The hope? That a rising tide will help all schools in the archdiocese survive the mounting challenges.

When it comes to challenges, there are many, Frett and Smith were quick to underscore during their nearly two-hour presentation at BC High. Though specific reasons for school closures vary, one of the biggest challenges plaguing schools has to do with the school leaders themselves. With little to no training for some Catholic school administrators and directors—including pastors and principals—in financial literacy and data analysis, many smaller Catholic schools are simply lacking the personnel with the kinds of skills that the schools need to be able to compete and survive.

Another pain point for many of the schools is an inability to recruit and adequately pay teachers. CSSN’s data shows that Catholic elementary school teachers made 55 percent of what public elementary school teachers in the state made in recent years. (Despite this startling gap, Catholic schools have an 88 percent teacher-retention rate, almost a miracle itself.) As for student recruitment, the overall decline in Catholic school enrollment has stabilized in recent years.

It hasn’t helped that there’s been a lot of concern about leadership at the Archdiocese of Boston’s Catholic Schools Office. Next month, the superintendent of Catholic schools, Thomas Carroll, will step down, marking the end of a rocky stretch for the administration. When he was appointed in 2019, Carroll was sold as an innovative leader, and stakeholders had high hopes he would breathe new life into the office—long a source of confusion for families. Behind the scenes, though, stakeholders quickly realized that his conservative background was a bad cultural fit in a historically liberal city—and clashed with the Kennedy-leaning supporters underwriting the schools. “From the start, it felt like Carroll’s mission was to reconvert the liberal heathens of Boston,” says a career Catholic-schools teacher and administrator who requested anonymity. Carroll did not respond to a request for an interview and at presstime, his replacement had not been announced. On top of it all, Cardinal Sean O’Malley’s tenure as the head of the Catholic Church in Boston is coming to an end, opening up another front of uncertainty about the future direction of Catholic schools.

Then, of course, there’s the burning real estate question. Many families believe that some schools’ biggest asset—the high-value land they sit on—is actually what makes them most vulnerable, given that the archdiocese—or whatever religious order owns it—can cash in on it as needed. Matignon, for instance, occupied more than 7 acres in Cambridge, one of the most expensive real estate markets in the country. The property has been assessed at around $30 million. When asked what the church will do with the money from that sale, church officials did not provide an answer. Bishop O’Connell, though, said that the church did everything it could to avoid shutting the school down. “We tried to save that school,” he says. “We shored them up with money; we put millions of dollars into it to try to save it. But in the end, it was unsavable.”

Many families believe that some Catholic schools’ biggest asset—the high-value land they sit on—is actually what makes them most vulnerable, given that the archdiocese can cash in on it as needed.

Sometimes, a closure is not a dead end but part of the road to resurrection. Standing outside Saint John Paul II Catholic Academy’s Columbia Road campus, it’s hard to notice any changes since it was Marty Walsh’s beloved St. Margaret School. But now, just off to the right, there stands an updated wing with a modern gymnasium and cafeteria.

The hybrid building tells the story of adaptation and survival, one that speaks to changing demographics within the church and an eye toward sustainability. This building and two other locations in Dorchester comprise the St. John Paul II Catholic Academy, a regional school formed from the merger of seven parish schools in 2008 in response to widespread financial struggle following the archdiocese’s sex-abuse scandal.

SJP2, as it is known, is the largest Catholic elementary school in New England, and it is within these walls, some would argue, that the real, on-the-ground, everyday battles for Catholic education are waged—far from the heavily endowed halls of BC High, just down the road. The scene is far different from the way many of us remember Catholic schools: Here, young lay teachers, not nuns, are leading groups of children through the day’s lessons. The day I visited was during Catholic Schools Week when students get to trade their blue plaid uniforms for cartoon- and dinosaur-themed pajamas for a day. “It would be hard to call this a growth industry, but it’s important to note the survivors have shown a bit of a Renaissance lately,” says Jack Connors, whose efforts through the Campaign for Catholic Schools, which he cofounded to help sustain urban schools, were instrumental in this institution’s opening, as well as in the formation of other urban Catholic regional academies.

When I asked Katie Everett, the executive director of the Lynch Foundation, an organization that has been underwriting Catholic education for decades, about the closures, she reframed the doom-and-gloom narrative. More than a sign of imminent demise, she noted, closures are more of a right-sizing, a necessary reaction to shrinking demographics across the city, one that is also affecting Boston Public Schools. “We recently lost five schools in the archdiocese, but we serve almost the same number of children—less 200 or so—and now we have the opportunity to grow,” Everett says.

Indeed, consolidation has helped some schools thrive. At SJP2’s Columbia Road location, Principal Christin Durazo says their three-campus model works because they can pool the resources of a large school to help lower-income families who require financial aid while providing a “small school” feel and individualized attention that attracts many non-Catholic parents as well. According to Durazo, about 50 percent of the Columbia campus’s student body is non-Catholic. Parents there include Kristin Prout, a single mom who says she had “a laundry list of concerns” about her son’s options at BPS. A visit to the Lower Mills campus of SJP2 quickly sealed the deal. “It was clear that they teach the whole person, not just academics” in the classroom, Prout says. Meanwhile, in the Merrimack Valley, Lawrence Catholic Academic—which was formed by the merging of two parochial schools in 2010—has seen increased enrollment every year, and just received millions in donations to construct an entirely new school building.

Even if enrollment is high at some schools across the archdiocese, there is still the problem of finding enough high-quality teachers to work there. In fact, many local experts in education agree that the wage gap for Catholic school teachers is the biggest threat to this educational model’s survival. To that end, the diocese has recently placed a greater emphasis on teacher recruitment, establishing partnerships with educational institutions like the Lynch Leadership Academy and the Urban Catholic Teacher Corps, which offers a two-year program in which teachers receive a tuition-free master’s degree with free housing and stipends while teaching in a partner Catholic school. “It could be all about doom and gloom, or you could say it’s been a rough 60 years, but there are some green shoots,” Connors says. “I see more support from donors, teachers, and parents than ever before. I see the glass half-full.”

Still, for the many students of closed schools, it is hard not to see an empty glass.

The Cambridge Matignon School closed in 2023, giving rise to concerns that the Catholic church may be divesting from its schools. / Photo by John Phelan

At least once a week after school, Alexiah Lingley can be found driving around the parking lot of her shuttered alma mater, Matignon, feeling nostalgic. Sometimes, she goes alone; other times, she meets friends or runs into other alumni, all hoping to catch a glimpse of their favorite memories. Little has changed on the grounds except for the addition of “No Trespassing” signs and boards on some of the windows. “We just go to have some sort of connection,” Lingley says. “It’s been really hard for a lot of us.” Now 18, she’ll graduate from one of Matignon’s longtime rival high schools this month. Some of her friends landed at other Catholic schools, while others went public.

Lingley is hardly the only student affected by the closure. Jenn Silva-Matos, the former Matignon parent, says her son has reluctantly settled into his new Catholic high school. Because of athletics, she still speaks to many of the former Matignon parents, many of whom tell her their children are struggling to adjust. “Some kids have completely fallen off the grid in terms of school and mental health,” she says.

Church officials and spokespeople seem less focused on present attachments—the ties to a building, a school, a memory—and more on the big picture, namely, actions that will ensure the survival of this educational model so it can serve children for decades to come. But seeing so-called right-sizing up close is very different from getting a bird’s-eye view of its impact. “An abrupt closure destroys the confidence in the system,” says James Walsh, who leads the Campaign for Catholic Schools. “It’s very personal, and it’s traumatizing.”

Meanwhile, feeling betrayed during one’s youth can take a toll on Catholic schools’ other mission—to get people in pews. Though efforts to save and steer Catholic schools in the archdiocese have been plentiful, many teachers and families told me they don’t feel as though they’ve had a say in what’s been happening. Most are unaware of the new initiatives being rolled out.

Being heard may be more important than ever. With Cardinal O’Malley’s time as leader drawing to a close and the pending announcement of a new school superintendent, the Archdiocese of Boston and its schools are at a crossroads. The decisions being made right now about what leadership to entrust, which schools to invest in, how schools use data and embrace new realities, and who has a seat at the table will determine the future of one of Boston’s oldest cultural and educational institutions. “Morals, ethics, and a Catholic education remain the critical platform for the church, and I pray that it grows,” says Bishop O’Connell, who has been tasked with finding the next superintendent. “Many of our schools are very strong, but there are some that are vulnerable. My parting shot is to encourage parishioners and families not to be passive.”

First published in the print edition of the May 2024 issue with the headline, “Can Catholic Schools Be Saved?”