Mother of Merci

By Nathaniel Parish Flannery

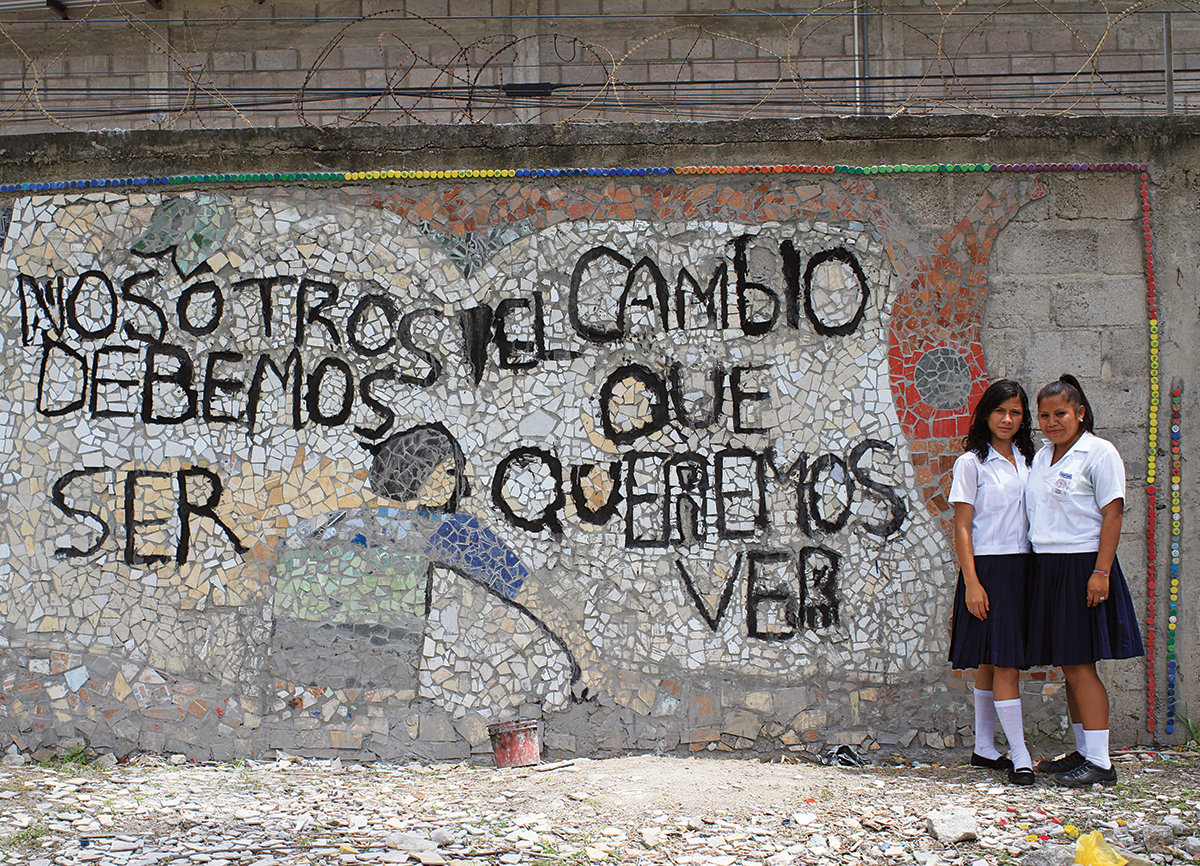

Fifteen-year-old Merci (left) was left behind by her mother—who fled to Boston—to finish school in Honduras. The mosaic on the wall of her high school reads, “We must be the change we want to see.” Photograph by Nathaniel Parish Flannery.

In the belly of a brown-brick apartment building in Allston, a pastor with silver teeth and a thin mustache is preaching hope and miracles to a crowd of Central American migrants, but Nixia’s mind is on the 15-year-old daughter she abandoned 2,000 miles away. Last February, gangsters gunned down Nixia’s father, a coffee farmer in the small village of El Playón, Honduras, for refusing to pay their extortion, forcing Nixia and her sisters to flee or risk a similar fate. The only safe harbor was with relatives in Boston, but the journey through Central America and Mexico into the United States was too treacherous and strenuous for her to bring both her children. She had to make an impossible choice. She brought three-year-old Dario with her. She left Merci behind.

Sweating and shouting in Spanish, the pastor cries, “Sometimes we say, ‘Why me?’ Have you heard people say, ‘Why did this happen to me?’”

Nixia presses her eyelids shut and pulls Dario tight against her leg.

“Migrants are dying tonight,” the pastor says. “There are those without lawyers. They say the American Dream is over, but He has the last word. The time of miracles is not over!”

Nixia finds the words soothing, but the feeling fades when a Guatemalan woman in a black dress tells the congregation how after eight years she recently reunited with her son and daughter. Sobbing, the woman nods toward her son and squeezes his shoulder. “I hope that in the name of God we can be together now.” When the daughter turns and embraces her mom, Nixia sniffles. It is impossible for her not to think about Merci. On the walk home, with Dario at her side, she says, “With him it’s easier. I can hug him. But Merci is far away. I ask God to help me raise her.” She sends Merci text messages. “I tell her I love her,” she says.

Sometimes Merci responds, but she’s not always as sweet. She accuses Nixia of walking out on her and favoring Dario. The words are painful to read, but Nixia needs Merci to stay put and wait to see whether Nixia’s petition for asylum in the United States is accepted, which would allow her to stay. Nixia doesn’t want to uproot her daughter from school and her entire life in the mountains of Honduras to bring her to Boston, only to be shipped back.

After the service, Nixia pushes Dario in his plastic stroller down Harvard Avenue, past a bar playing thumping electronic music. It’s a clear, Indian summer night in September. A college-age student in a crisp gray dress shirt stands by an open window and stares at her as she passes. Nixia looks straight ahead at the sidewalk in front of her. She doesn’t like interacting in public. Her English is limited and the bulky tracking device on her ankle makes her feel like a criminal.

On April 11, following a grueling weeklong journey north, Nixia and Dario had arrived in Texas and were promptly detained at the border by U.S. immigration agents. But they were among the lucky ones. Mexicans caught crossing the Rio Grande are usually repatriated, but because Nixia is from Honduras—a “non-contiguous” country, in Border Patrol jargon—she was allowed to ask for, and received, an asylum hearing. She is one of more than 250,000 non-Mexican migrants, most of whom came from Central America, who were detained by the United States during the 12 months prior to October 2014. Like many of her countrymen, Nixia fled a surge of gang violence. In Boston, she is free to work, shop, and move around the city, but court officials use the black plastic tracking device to keep tabs on her movements and prevent her from leaving the state. Nixia doesn’t like the stares people flash her when they see the ankle bracelet, which she knows is commonly used to monitor convicts.

Walking up to her apartment, Nixia looks at the strip of asphalt in front of her porch in Allston. Her building is filled with Central American immigrants, mostly single men or families, like hers, that have been torn apart. They share the apartments and sleep together in cramped rooms. The building is a Spanish-speaking enclave, a brick tenement that long ago housed arrivals from Ireland and Italy. “When [the men] urinate outside, it smells so bad,” she says, watching a drunken neighbor stumble out of his car. “And they blow kisses at me.” It is a long way from the dirt roads and sparsely populated farmlands of her childhood.

Before bed, Nixia prays for God to protect Merci and for her daughter to be patient. An asylum judge told Nixia that she will have a hearing sometime in 2015. For now, both mother and daughter must wait. As much as she wants to see Merci, she tries to assure herself that she’s made the right decision and that leaving Merci in school trumps the emotional need to be with her. Sometimes, it feels like an impossible position. Sometimes, she questions her resolve. Nixia is like a survivor in a raft, tossed by currents and forces beyond her control.

Looking out over Honduras’s Montecillos Mountains, outside a dusty white shack that serves as one of two main police outposts for the region of Comayagua, where Nixia grew up, Merci and her grandmother Amerita inspect an old blue pickup truck that has been riddled with bullets. It’s mid-afternoon in September and the sun overhead is blazing. Merci walks past the driver’s door, which is punctured with half-inch-thick, rusty bullet holes, and picks up an unused round with a sharp, pointed tip. Unfazed and smiling, she holds it up and says, “Look, a bullet.”

Unlike in much of Honduras, the daily threat of violence for the roughly 900 residents in Merci’s hometown of El Playón isn’t the notorious MS-13 and Barrio 18 gang members whose tattoo-covered faces sometimes make the U.S. evening news. Instead, villagers warn their children about the Espinoza gang, heavily armed mountain men who wander the nearby hills and coffee farms murdering and extorting residents.

Honduras’s population is smaller than southern New England’s, but it is spread out over a verdant landmass the size of Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire put together. From an airplane, the cities, towns, and settlements are barely visible among the green expanse of rainforest and mountains. Merci and Amerita live on the outskirts of El Playón, near a wide river that separates the family’s coffee farm from the unpaved road into town. Most locals ride dirt bikes. Even four-wheel-drive trucks struggle for traction on the steep, rutted trail that connects El Playón to nearby coffee-growing hamlets. Along the town’s main road are a one-room schoolhouse and a few homes converted into small stores selling vegetables and live chickens.

Like much of Honduras, El Playón is not a wealthy town, and became a dangerous place to live only during the past several years. For the most part, petty crime doesn’t pay and thieves struggle to find much worth stealing. But the emergence of the Espinoza gang in 2010 kicked off a new reign of terror. For the first time, local thugs began employing the brutal tactics perfected by Mexican crime syndicates and urban Central American gangs, using savage and highly visible violence to force businessmen and farmers to hand over their coffee earnings. In El Playón, no one is immune. Extortion and violence, rather than crop-killing blights, are now the central risks for the town’s dwindling number of farmers and their families.

The Espinoza gang is also notorious for its brazen attacks on local law enforcement. Inside the small white police station, Officer Juan Garcia says that in the past two years, 11 fellow officers died during gunfights with the gang. During the height of the confrontation with the Espinozas in 2012 and 2013, the Honduran Army sent trucks and highly trained Cobra special forces to patrol the isolated roads outside of El Playón and protect its people. “For a while there were 200 police here,” Garcia says. “Ten or 20 weren’t enough. You need 10 or 15 police trucks [to go on mountain patrols].” He flexes his index finger as if he were shooting a gun. After killing several high-ranking Espinoza members, however, the tactical units moved on to other assignments, leaving the locals with little protection. Today, the few remaining policemen share a machine gun and a dirt bike. Garcia says he does travel on the mountain road to El Playón, but never alone.

In 2012, San Luis—less than 30 miles from El Playón—earned the unwelcome distinction of being the most violent city in Honduras, with 342 murders for every 100,000 people. Boston, by comparison, reported 58 murders that same year. To put this in perspective, if the 4.5 million people in Greater Boston experienced the same homicide rate as San Luis, they would see more than 15,000 murders each year. For now, Garcia says, the violence has temporarily tapered, but “when the harvest season comes it could get complicated. We’ll have to get reinforcements. If we don’t, it will go back to being what it was like before,” when fresh graves dotted the highlands.

As the breeze picks up and the clouds settle over the mountains in the distance, Merci’s grandmother Amerita buys two gallons of gas from a neighbor’s handheld container and climbs into an aging yet rugged Toyota pickup truck. Merci and two boys from the neighborhood hang onto the sides of the truck bed. Amerita’s daughter-in-law, Marina, joins them. In first gear, the truck labors up a steep dirt road, the speedometer needle hovering around the 10-miles-per-hour mark. On the right-hand side, there’s a cliff leading down to a green expanse of mountains that fade into the mist. It’s hard to tell where the ridge line ends and the clouds begin. As the truck rattles over the ruts, Marina looks out the window and points. “They killed a boy there and shot his father,” she says. The truck’s tires chirp as they strain for grip on a section of erosion-exposed rock. Driving past a farm, she says, “They killed another man here.”

Marina explains that the Espinozas “stay up in the mountains. They come down to steal milk, bread, and money.” She points to another ranch on the right. “They killed a man here. Now his wife doesn’t take care of the farm. It’s in bad condition.” Looking out the window to the left, she says, “The police killed two [Espinoza members] here in an abandoned house.” The truck crosses over a narrow cement bridge, passing over a churning current of water below. The driver suddenly swerves to avoid a 4-foot hole in the road and Marina’s eyes widen. “We almost fell into the ditch,” she says. “Imagine how long it takes the police to get to us. They can’t catch the criminals when something happens.”

Perhaps it is her proximity to lawlessness that makes Merci want to be a lawyer. With her mother living in Boston, she feels torn between two worlds—she can either finish high school here and study law in Honduras or risk taking the undocumented and dangerous trek alone through Mexico with an untrustworthy “coyote” to be with her mother. More than 68,000 children traveling without parents were caught crossing into the United States during the 12 months following October 2013, a 77 percent increase over the same time period the previous year, and border agents indicate that the number of young girls trying to cross over is rising. Merci worries about Mexican drug cartels such as Los Zetas—known to prey on migrants and sometimes traffic them for sex—as well as crossing the Rio Grande. “A whole heap of people have drowned,” she says. When she thinks about her mother’s journey to Boston, she smiles and says, “Thank God she wasn’t drowned in the river. I was really scared she’d get pulled under.”

Still, even at 15, Merci feels ready to take on the risks that come with living as an undocumented immigrant in Boston, where rents are high, steady jobs with decent pay are scarce, and she doesn’t speak the language. Back at her house in El Playón, Merci listens to Rihanna and Eminem songs, even though she doesn’t understand the words, and she wraps herself in a Spider-Man blanket while watching the Cartoon Network.

“I miss seeing [my mother] in person [and] hugging her,” she says. Like other members of her family, Merci is weighing her options. She knows that it’s a difficult and complex decision, and like many teens, she is frustrated that her mother, 2,000 miles away, is in charge.

On a sunny afternoon in mid-September, Nixia and her sister Sergia wander down a street in East Boston toward the entrance to Centro Presente, an advocacy organization that assists Central American immigrants. They have a meeting with the group’s executive director, Patricia Montes, to learn more about their applications for asylum. In the alley just outside the agency’s door, a Salvadoran woman who fled her country’s bloody civil war during the 1980s is selling mangos, oranges, and limes. Montes greets them at the doorway. “Hola,” she says, pulling the sisters in for a hug.

Wearing a white pearl necklace and tan leather jacket over her dress, Montes says she is optimistic about Nixia and Sergia’s chances for asylum. This is Nixia’s first time in the United States. Sergia has been here before. She traveled to Boston in 2004 to earn as much money as she could cleaning homes and waiting tables, because none of the jobs at home paid as well. Like many Central American and Mexican migrant workers, she did not come with a dream that her grandchildren would be born in the United States and become successful lawyers or businessmen—she simply hoped to stay long enough to save for a new house and a better life in Honduras. In 2012, Sergia returned to El Playón, but she did not expect to be affected directly by the violence. When her father was killed, she returned to Boston. She now may have to wait up to two years to find out if she and Nixia will be granted asylum. Montes reassures Nixia, who buses tables at IHOP, and Sergia, who now works at a Mexican restaurant in Jamaica Plain, that during those two years they can work.

The likelihood that either of their cases will be successful, however, isn’t clear, even to longtime attorneys and activists. Under U.S. law, refugees seeking asylum must show that they are in danger of persecution for voicing an unpopular political opinion or for belonging to a specific ethnic, political, or religious group. Their government must also be unwilling or unable to protect them. Most successful applicants for asylum are fleeing savage dictators or gruesome civil wars. Unfortunately for Nixia and her sisters, the law does not explicitly include individual victims of generalized crime, such as gang-related violence, making asylum a long shot for many Central American applicants. Between 2003 and 2012 the United States granted asylum to more than 250,000 refugees from more than 100 countries. Less than 4 percent of those came from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras combined. Still, Montes believes the sisters have a solid case and can beat the heavy odds against them. “The gangs, the violence, that’s why people come,” Montes says. “They killed your dad.”

Their father’s murder was just one drop in the ocean of blood that has been spilled during the storm of violence ravaging Honduras. You can trace the country’s current problems back to the latter half of the 20th century, when the United States regularly meddled politically and militarily in Central America in an effort to safeguard U.S. business interests and quash leftist governments that threatened to take power. The United States, for instance, helped topple Guatemala’s government in 1954 and deployed the CIA in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s to help right-wing regimes stamp out socialist uprisings in Guatemala and El Salvador, clashes that began as leftist revolts against U.S.-backed regimes. Honduras, meanwhile, served as a base for covert operations designed to undermine the leftist Sandinista government in Nicaragua and experienced a massive military buildup. As a result of these conflicts, and the economic hardship, large numbers of refugees fled north.

Some of these immigrants, most notably in Los Angeles and northern Virginia, soon became involved in violent gangs such as MS-13. However, when the U.S. began aggressively deporting migrants with criminal records in the late 1980s and 1990s, they did not coordinate with Central American governments—which found themselves unprepared for an influx of hardened gangsters and outlaws. With no jobs or social connections to their homeland, these hoodlums formed or joined gangs in Central America at a time when U.S. pressure on planes and boats carrying drugs north from Colombia forced cartels to adopt overland routes through Central America. Quickly, these gangs took control of prisons and helped facilitate the drug trade, creating large extortion networks aligned with corrupt local governments. Murder rates surged. In Honduras, the turbulent combination of local gangs with connections to Mexican and Colombian drug traffickers and access to the pool of weapons left over from the region’s civil wars overwhelmed weak government institutions, pushing out a new steady stream of refugees. According to Columbia University provost John Coatsworth, who was the founding director of Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, “We are living with the consequences of misguided policies from the 1980s that led to hundreds of thousands of families fleeing to the United States.”

In July President Barack Obama asked Congress for $3.7 billion to respond to the immigrant crisis in the United States. While $300 million was earmarked to facilitate deportations to Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, there was little attention given to addressing the root causes of the northbound exodus. “It’s never been more difficult to migrate,” Montes says, “but people still [do it]. The situation in Honduras is out of control [and] they are more scared of staying in Honduras,” which is currently the most violent country on Earth, excluding active war zones. Here in Boston, Montes says she works with five to 10 new families a week, most of whom fled the bloodshed in Honduras.

At the Centro Presente office, there is a wall poster that reads, “OBAMA: STOP TEARING OUR FAMILIES APART.” Currently, the United States sends home more than 1,200 unauthorized immigrants every day, and Montes is upset with Obama’s zeal for deportations. Nodding toward the poster, she says, “It’s a failed strategy but it’s still implemented. [But] it’s not a political game. It is life or death. Nixia, Sergia—if Obama deports them, they could die.”

In the backyard of a concrete home not far from the center of El Playón, Wilmer, father to one of Merci’s cousins, is butchering a freshly slaughtered cow. Round-bellied and middle-aged with gray hair, he once lived in North Carolina but returned home to run a series of small businesses, including a convenience store and a commercial tilapia pond. Working to prepare a set of ax-cut ribs, he watches one of his workers slide the cow’s organs across the slick cement floor through a hole in the fence on the edge of the patio. “We do this every Sunday,” Wilmer says. “The [meat] is for the majority of the town.”

Medardo, one of Merci’s distant cousins, watches as Wilmer’s worker strings the cow’s severed leg up above a wheelbarrow and slices off chunks of meat. Medardo’s shirtsleeve is pinned up at the armpit, covering a rounded stump. He lost his arm when the Espinoza gang ambushed him and murdered his son for refusing to pay them. Wilmer’s own boy, Wilmer Jr., who lacks his father’s heft, stands in sandals, balancing his weight carefully as he helps his dad trim the rack of ribs. He has a tube of scar tissue running through the fat on his back and a series of jagged white scars from six bullet wounds. His ankle and leg were surgically repaired after the Espinoza pistoleros shot him because his father would not give in to their demands. “So many people are migrating because of the crime,” Wilmer says. “People used to go for economic reasons, but now it’s because of security. The people who work hard, who live better, are targets. So people leave.” For those who stay and work, particularly coffee farmers who must transport their goods after the winter harvest, “You have to be brave,” Wilmer says. “It’s putting your life at risk every day.”

Despite the constant threat from gangsters, El Playón can be a dull town. Merci describes it in two words: scary and boring. In the afternoons, men without jobs kill time playing soccer in a field next to the river. Most people attend the nightly evangelical services held in one of the three nearby churches. Wilmer’s weekly butchering sessions are a social highlight for many. Even as Honduras buckles under the pressure of an ongoing economic crisis and a surge of organized crime, many aspects of community life remain the same.

At home, Amerita sets a blue metal coffeepot down above a fire pit on her back porch. The early-morning fog clouds her view of the ridge behind her banana patch. She never saw the gangsters in the hills who killed her husband, but she heard the gunshots and knows that some of the triggermen have eluded the police and are still hiding in the mountains, seven months after his murder. She can picture the hunk of tire tread and the scraps of metal that still sit on the side of the road where the gang murdered her husband and then set his truck on fire.

After Amerita recovered her husband’s body and attended his funeral, her family braced for a follow-up attack. Unable to sleep, and constantly worried that the gunmen would come for them, Nixia and Sergia fled to Boston. Amerita, though, had to stay to take care of Merci. She was also reluctant to cross through Mexico and was unsure of how she’d make a life for herself in Boston. She would like to see Nixia and Sergia, but wants to visit her daughters in the Unites States by plane, not by wading across the Rio Grande like a felon. “I love it here,” she says. “The place is good but people from outside have made it bad.”

As the sun rises, Merci’s uncle, Henry, stops by to help Amerita prepare a traditional Honduran soup, taking Wilmer’s freshly cut ribs out of a plastic bag. Amerita sends one of her farm workers behind the house to look for herbs. A passing neighbor sells her three skinny yucca roots and a handful of plump green zucchinis. Henry, a muscular 30-year-old wearing a Pabst Blue Ribbon shirt, helps Amerita peel vegetables for the soup. “I call her usted,” he says. “It’s a sign of respect. I use it for all my elders.” Amerita smiles silently, but her eyelids flutter in a show of appreciation. Sixty-three years old, but still agile, Amerita works purposefully and lets Henry tell his story.

Henry lived in Boston from 2007 until 2013. Unlike Nixia, who fled the gang violence, he was just another migrant worker looking for a better-paying job. He painted houses in the suburbs from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. and also worked nights cleaning an office near Coolidge Corner. He got along well with the Salvadorans and Guatemalans on his paint crew, but often struggled to communicate with his English-speaking coworkers. On Saturday, his day off, he ate at Anna’s Taqueria in Brookline and went fishing in the Charles River, drinking cans of Corona, Modelo Especial, and Miller. He never tried Sam Adams. Nor did he ever see a café in Boston that sold Honduran coffee. The farmers in El Playón sell their coffee to middlemen, who sell it to other middlemen. The beans get mixed together with grounds from many producers, forming a faceless blend.

After six years, Henry felt he needed to make a choice: stay in Boston, where he enjoyed making money and watching Red Sox games on TV, or return home with the money he’d saved to be with his struggling family. “The good thing [about Boston],” he says, “is that there’s a lot of work. Life is better. The bad thing is that my family is here and they have problems.” Ultimately, Henry chose to return to Honduras.

Henry is proud that he was able to save enough money to buy a newly constructed house in El Playón, plus a flat-screen TV and a collection of American DVDs. He now has a wife, a young daughter, and all the household appliances he saw in Boston. Still, he often regrets coming home. “Here there’s no money,” he says. “There are a lot of problems. You can’t live well. You are not safe because of the security problems.”

Sometimes Henry feels trapped, surrounded by low-hanging clouds and insulating rows of mountains that stretch across the horizon as far as he can see. He has already watched the DVDs he brought home with him, and the local TV stations don’t regularly broadcast Red Sox games. He often thinks about returning north but is worried that the journey through Mexico has become too dangerous. He watches Amerita ladle out spoonfuls of soft, boiled potato and parsniplike yucca root along with heaps of soggy, stringy meat. He sets his bowl down on the table. It reminds him of one more thing he misses from the North, saying, “It’s like the Irish food [in Boston].”

On a chilly September day, Nixia’s sister Sergia sits near a sprinkler in Allston’s Hooker/Sorrento Playground. Her son, Gustavo, a shy 12-year-old who attends school in Jamaica Plain, climbs through the jungle gym and glides down a slide. At 31, Sergia is seven months’ pregnant and tired. Wearing a blue polar fleece and sandals, she rests her hand on her stomach and recalls the first time she came to Boston, in 2004.

It was something of a miracle that she made it. Pregnant with her second child, she trekked through Central America and across the Rio Grande, where she was detained by the U.S. Border Patrol. Sergia claimed to be Mexican and was sent back across the border. She was arrested by Mexican migration officers but they let her go—which enabled her to try again, and this time she successfully crossed into the United States. “I was blessed,” she says. From Texas, Sergia rode what she calls the “Greyhouse” bus to Boston and moved in with relatives. She worked hard, studied English, and found work as a waitress. She laughs when describing how she learned to talk to her customers. “I’d say, ‘Hey, how you doing? Are ya reddy-ta orda?’” dropping her Rs in a Honduran version of a Boston accent.

For Sergia and Nixia, life in Boston is hectic and doesn’t have the same sense of community as in El Playón, though bumping into cousins and friends from Honduras, as well as taxi drivers and pizza deliverymen who speak Spanish, helps them feel less homesick. With a growing Central American community, strong social programs, and an absence of long-standing racial tensions between Hispanic migrants and locals, Boston is a relatively welcoming place.

Each day, Sergia wakes up early to clean her home. She vigorously sweeps the floor, even the tiny space between the stove and window. She mops the kitchen tiles and scrubs the door to the small room in Allston that she shares with Nixia, Dario, and Gustavo. Sergia tries to control what little she can and likes to see her home spotless, even if no one else cares and the outside smells like urine and is littered with garbage.

On the upside, Sergia says, Allston has minimal problems with gangs and violent crime. Alejandra St. Guillen, director of the Mayor’s Office of New Bostonians, says that for most migrants there are three concerns: “One is safety,” she says, “the second is economic opportunities, and the third is education and future prospects for their kids.” Boston provides all three. Still, rent in Allston, cheap by Boston’s standards, is higher than in other cities. And learning to live through the winter has been a brutal adjustment. But Sergia and Nixia believe that they can find better-paying jobs here than in Texas or other parts of the country. As St. Guillien explains it, “Migration starts with a few people from one place and then people go where they have family and friends from their town.” Sergia and Nixia have relatives here. Anywhere else they’d have to start from scratch.

That they have family in Boston is partly why Sergia and Nixia struggle to keep in contact with family in Honduras, and fear they are losing touch. Like Merci, who feels torn between her mother’s life in Boston and her own world in El Playón, Sergia feels divided. Part of her would rather be home in Honduras. “I wish I could turn time back,” she says. “It was really nice. I had my cows. I took care of my properties. I love the farmland. It’s nothing like here, where I have to work every day. It’s not the same working for someone else as it is working for yourself.”

Without legal status or a high salary, Sergia says her quality of life was better in El Playón than it is in Boston. However, she will not return voluntarily for the simple reason that she does not feel safe in Honduras. “I’d like to be there, but it scares me too much,” she says. “I couldn’t sleep. I imagined they’d kick in the door and shoot up the house. I said, ‘It’s better to go.’”

Walking toward a relative’s apartment in Allston, Sergia passes between two American flags. “Now I don’t have an American Dream,” she says. “I wanted a house, a car. That’s what migrants want. That’s the dream. And I got it. But ask Nixia if she has [a dream.] It’s her first time here.”

A few minutes later, Nixia arrives at the apartment and settles into a seat at the kitchen table. She talks about Merci, braving the threat of violence as the winter coffee- harvesting season begins. Nixia has a dream, but it’s one shared by mothers everywhere: to live someplace safe with her children. She looks toward the living room, which is adorned with photos of her father and family in El Playón. She has seen Merci post messages on Facebook that say, “I miss you too much Mamiii. I can’t take it anymore.” She knows Merci needs her mother, but for now, until the asylum issues are resolved, Nixia once again assures herself that it is best to stay in Boston and to leave Merci in El Playón. She prays Merci will be patient, and wait. Otherwise, if Merci comes, she’ll have to come with a “coyote,” unaccompanied by a parent and alone.

Last names were omitted to protect Nixia, Merci, and her family.

Update: On Thursday November 20, President Obama announced a sweeping plan for executive action to protect millions of undocumented migrants from deportation. While his initiative will protect the parents of U.S. citizens and migrant workers who have lived in the United States for more than five years, it will not help the tens of thousands of Central American refugees who—like Nixia and Sergia—have recently fled violence in their homeland and have come to the United States seeking asylum. For now, the Central American families who have arrived in Boston from their homes in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala must continue to work their way through the established and often lengthy asylum process. And hope they are allowed to stay.