The Rocky Road of Peter Marciano

Football star, politician, pride of Brockton. Peter Marciano seemed primed to outshine his legendary uncle, Rocky, in fame. Then he got clobbered by the hit he never saw coming.

Rising up from the ground on the outskirts of Brockton, the two-ton, 20-foot statute of Rocky Marciano looms over the city like a god. Wearing boxing trunks wrapped around an Adonis-like body, he stretches his muscular right arm out to deliver the crushing knockout punch against Jersey Joe Walcott that ended their epic 1952 championship fight. In many ways, the larger-than-life bronze sculpture is more reminiscent of one depicting a world leader than a local sports hero, built as a testament to the 49–0 record—Marciano’s the only undefeated heavyweight champion in history—that put this scrappy blue-collar town 25 miles south of Boston on the map.

Born in 1923 to Italian immigrants who worked at a shoe factory, Marciano grew up on the south side of the city with two brothers and three sisters. He played baseball and football at Brockton High but dropped out before entering 11th grade, working instead as a ditch digger and as a chute man on delivery trucks. As a teenager, he learned to punch a heavy bag, created by his uncle and hung in the basement. Then he was drafted into the U.S. Army, where he learned to box and began his career. Today, the slugger is celebrated as much for helping to inspire the movie character Rocky Balboa as he is for his work ethic and refusal to quit.

Since then, to be a Marciano in Brockton has been akin to growing up a Kennedy in Hyannisport—there are advantages, but the pressure is intense. It’s unfair to call the succession of Marciano family members failures, but no one could live up to the success or raw athleticism of Rocky. For generations, Brocktonians waited and wondered when the next Marciano hero might arrive and breathe fresh life into the struggling town that dubbed itself the “City of Champions.” Then came Rocky’s nephew Peter.

Born in 1967, Peter Marciano was a blast from the past: movie-star looks, fast as a bullet, and hard as nails. As a member of the Brockton High football team, he emerged as one of the state’s top talents, known for breaking tackles on his way to the end zone and leading his town to glory. But beginning in college, he held tight to a ghostly secret. This is the tale of the young man with the famous name who never saw the final hit coming.

One fall day in 1984, Peter Marciano woke up early, dressed, ate breakfast, and readied himself for the biggest game of his life: the state’s high school Super Bowl. Screaming fans packed into Foxboro’s rickety old Sullivan Stadium, joining scores of pro and college scouts there to get a glimpse of future New England Patriot Greg McMurtry and Odell Wilson and Sherrod Rainge, who both went on to play at Penn State. From the start, though, Brockton’s team captain, Marciano, ran away with the show.

On the opening play against Lexington, Peter caught the kickoff and ran nearly untouched into the end zone. The Boxers led 7–0. Lexington got the ball next but went three-and-out, punting the ball back to Brockton. Peter caught a pass on the very next play and ran it in for another touchdown. By the time the final whistle blew, he had scored all three of his team’s touchdowns in a 20–6 victory. Brockton High ended the season ranked number seven in the nation by USA Today.

In those days, Brockton was a mix of postindustrial blue-collar neighborhoods, gritty urban housing projects, and suburban enclaves. After Peter’s performance on the field, the town swelled with pride. “That high school Super Bowl win culminated in the biggest celebration in Brockton since my uncle won the world title back in 1952,” recalls Stephen Marciano, Peter’s younger brother. “Our Uncle Rocky brought so much pride and excitement to the city of Brockton, and now here we were decades later and my brother Peter was bringing that pride back to the city.”

From birth, Peter was a rambunctious child who tested boundaries. He wasn’t the best student but he devoured history books and could recite speeches by JFK. At the family dinner table, he often led conversations about World War II and the Civil War. Growing up on Dartmouth Terrace, a quiet side street on Brockton’s west side during the 1970s and ’80s, Peter was smaller than most of the kids in the neighborhood, but he appeared chiseled out of stone with a square jaw, a rock-hard frame, and dark-brown eyes. Known as a cocky guy with a chip on his shoulder, he fought on a weekly basis with Brockton toughs looking to stake claims to their own piece of the Marciano legacy. Instead of boxing, Peter preferred Brockton’s football fields as a place to channel his energy and aggression. “Growing up the nephew of Rocky Marciano was a pretty tall task, but I never felt the stress the way my brother did,” Stephen remembers. “Peter was the oldest son and he put pressure on himself to be great at everything he did, but people were gunning for him.”

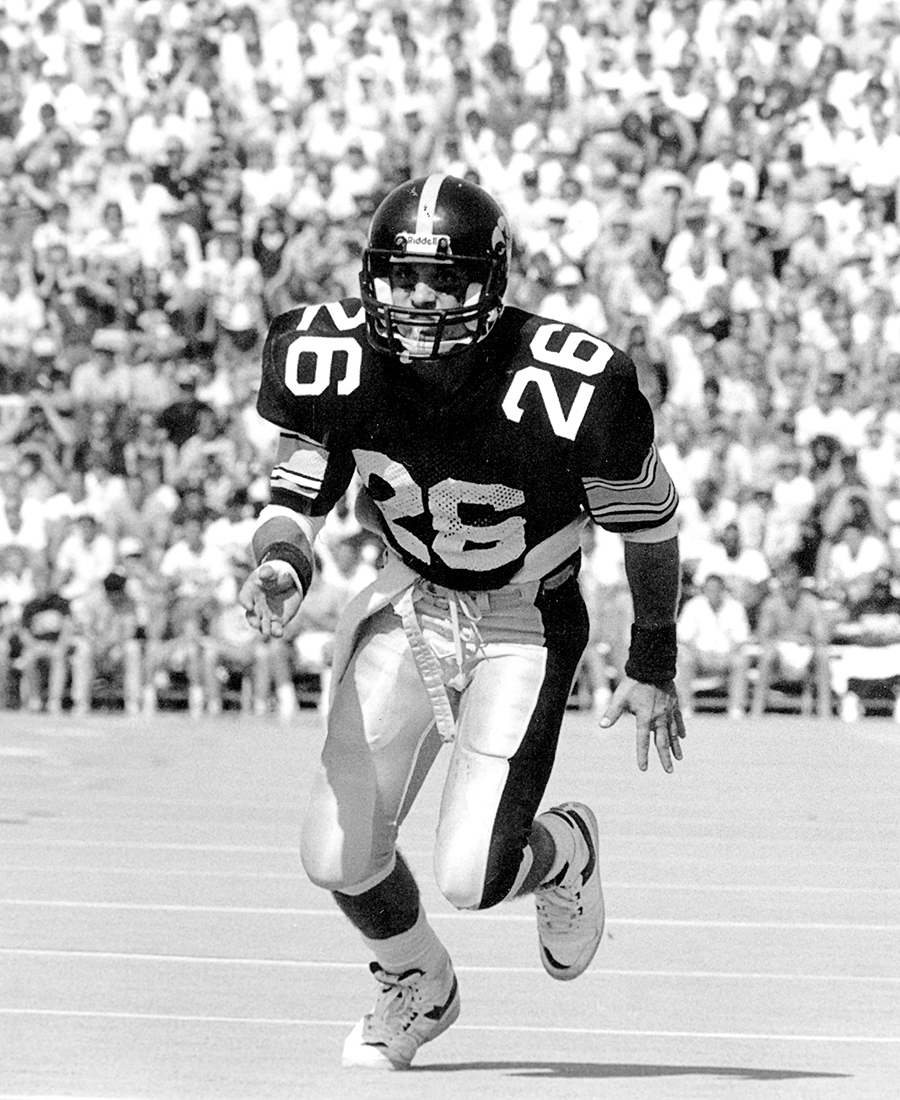

A receiver and kick returner in the mold of current Patriots star Julian Edelman, Marciano was known for lightning bursts of speed, ankle-cracking moves, and a knack for holding onto the ball even after getting blasted by a defender. He played football with the same reckless determination Rocky showed in the ring—both were willing to sacrifice their bodies and endure tremendous punishment in order to win. Peter sustained many head blows that his family believes caused several concussions. “Rocky often said that he never knew fear, even when facing tough boxers like Joe Louis and Jersey Joe Walcott,” remembers Peter’s father, Peter Marciano Sr. “I think my son had that same mentality with his own sport. Like my brother, he was obsessed to be the best.”

At the time, the coach of Brockton’s football team was a rising star named Armond Colombo—Peter’s uncle. He’d led the Boxers to the state title in 1972 and to the state championship game in 1979, so when a Marciano arrived the next year as a freshman, expectations soared even higher. The haters—and there were plenty—whispered behind Peter’s back that he was getting preferential treatment and playing time because of his name and his relation to the coach. When it came time to suit up, though, no one could argue with Peter’s nose for the end zone.

Off the field, Peter liked a good time but was hardly a Joe Namath– or Mickey Mantle–type partier, happy instead to hang out with his brothers, his teammates, or, more likely, one of the many young Brockton High ladies pining for his attention. Throughout high school, the explosive talent with a famous last name was heavily recruited by top Division I college coach es, including the University of Michigan’s legendary Bo Schembechler and Syracuse University’s Dick MacPherson, who’d later coach the Patriots. But Peter chose the University of Iowa, some 80 miles east of the pasture where his Uncle Rocky died after the small Cessna he was riding in hit an oak tree on August 31, 1969. On some level, the family legend called to Peter, and he wanted desperately to answer.

Iowa was a shock. For a kid who had grown up with the eyes of a city upon him, Peter felt lonely and isolated, suddenly a small fish in a much larger pond. The Marciano children had a tradition of calling their parents, no matter where they were, to say good night and exchange three simple words: “I love you.” On the other end of those first calls from Iowa, his parents could tell something was wrong. “Peter didn’t want to go to Iowa,” recalls his best friend and high school teammate, Rich Cogliano. “He wanted to be in Brockton. He was comfortable and at his best in Brockton.”

As Peter grappled with his new environment, he set out on a pilgrimage to the crash site where Rocky had died. It was a spiritual awakening of sorts for him, as he realized he had a chance to honor his legendary uncle while sculpting his own athletic legacy. Peter’s focus returned to football.

Carrying the weight of his family name, as well as the reputation of Brockton’s renowned football program, Peter had to prove himself all over again. One afternoon in the Iowa locker room, he walked up to the team’s biggest and toughest player and won a brawl, which earned him instant respect from his teammates. After all, says Cogliano, “We grew up tough.” He went on to lead the Big Ten in punt return yardage during his freshman year in 1986, averaging more than 10 yards per attempt, including running one back 89 yards to spark a stirring comeback win against Minnesota that propelled his team into the Holiday Bowl. By the time he graduated, Peter had played in multiple postseason games, including the 1988 Peach Bowl. To this day, he is the Big Ten’s second all-time-leading punt returner. “In my long coaching career, he’s one of the most inspirational leaders I ever had on one of my football teams,” says former Iowa Hawkeyes head coach Hayden Fry. “He was so proud of his Marciano bloodlines, and Rocky Marciano himself would have been very proud of his toughness.”

Success, though, came at a price. Collisions were unavoidable as Peter fearlessly rammed head-on into defensive players who were oftentimes much bigger and stronger than him. Peter’s body took a beating and injuries piled up. First it was his knee, requiring surgery, and then he blew out his shoulder. Soon, he was on a steady diet of Percocet—doctor’s orders.

Drugs of any kind were foreign to the young Marciano, who had never even smoked marijuana. In no time, though, they became a social crutch and his friends noticed a change in him. “Everybody dabbled in pills back then,” Cogliano recalls. “They were readily available. Everyone had a couple Percs and a couple beers before going out. But Peter would stay in sometimes when we were going out. That’s when I first thought, ‘Hey, that’s a little strange—he’d rather stay in with his Percs.’”

Following graduation, some of Peter’s teammates joined the NFL while he pursued his dreams with an Italian pro team. After a year of battling injuries, though, it was clear he needed to find a new line of work. Athletics hadn’t panned out, but he was still a Marciano. He decided to try his luck in Las Vegas, where the Mirage was more than happy to offer him a job giving starlets tours of the casino’s dolphin exhibit. With his famous name and matinee-idol looks, Peter was successful and having a blast. He wasn’t sure what he wanted to do in the long term, but Vegas felt like the right place to figure it out. At the same time, however, drugs were playing a larger role in his life. “When he went to Vegas is really when he started getting bad,” Cogliano says. “There were a couple of guys in Iowa who would ship him boxes of pills. When there were some friends’ weddings out there, people would call me afterward and say, ‘Boy, Peter was really fucked up.’”

Cogliano confronted Peter one evening, mentioning stories he’d heard of Peter being too loaded to climb a flight of stairs without tripping. Peter’s reply was to play it off: “‘Ah, don’t worry about it,’” Cogliano recalls him saying. “‘I just had a few too many.’” But by then, Percocet had given way to stronger opioids such as OxyContin.

Peter did his best to hide his growing habit from his family at home in Brockton. He started missing his nightly calls to his parents, and friends went weeks without hearing from him. Left in the dark, Peter’s father grew frustrated and concerned. Then the phone rang. Peter’s friend and former Hawkeyes teammate Mark Stoops (now the head football coach at the University of Kentucky) thought Peter’s family would want to know about their son’s suspected drug use. Stoops was right.

Peter Sr. drove to Logan Airport that night and took the next flight west. After landing in Vegas, he took a cab to his son’s tiny apartment and was relieved to find him alive, living amid a sea of prescription-pill bottles. “He looked like shit,” Peter Sr. says. “There was a sponge ball on the floor and I grabbed it and tossed it to my son. He fumbled it and we both watched it fall to the ground. My son didn’t know how to drop a ball. He was that good an athlete. I gathered up all the pills, flushed them down the toilet, and told him right then to pack his bags because we were going home.”

Together again in the City of Champions, Peter’s family staged an intervention and paid tens of thousands to send him to an addiction treatment facility in Maryland. When he returned healthy and sober, the Marcianos breathed a deep sigh of relief: The nightmare, they believed, was finally over. “We had no experience with this kind of thing, and we thought that if Peter went to rehab, he’d be cured,” Stephen Marciano says. “We didn’t talk about it outside the family because there was a stigma surrounding it. My brother was my idol and it was a little embarrassing to see him this way.”

In no time, Peter scored a job with the Massachusetts State Lottery under state Treasurer Joe Malone. “We bonded very quickly,” Malone says. “Between our Italian heritage and our Waltham-Brockton football rivalry [Malone graduated from Waltham High School], we had much in common. He worked hard and was very responsible.” Peter also had grand plans, setting his sights on conquering Hollywood and then Washington, DC.

In 1997, Peter reached out to a distant cousin, independent film director Frank Ciota, who was getting ready to shoot a small-budget movie titled The North End. One night, Ciota recalls, “Peter joined my brother Joe and me at Dolce Vita and Peter said, ‘I gotta take a piss.’ When he left, I turned to my brother and said, ‘What do you think?’ He said to me, ‘Think about what?’ And I said, ‘About Peter in the movie?’ ‘Can he act?’ my brother asked. ‘Who cares?’ I told him. Peter was electric on film and in person.”

Marciano received a small role in the film but couldn’t suppress the fighter in him, pushing for more screen time at the expense of the film’s star, Hollywood actor Frank Vincent of Goodfellas and later The Sopranos. “Peter grabbed me and pulled me aside and says, ‘Frankie, no offense, but people don’t want to see this old dude [Frank Vincent],” Ciota says. “They’re buying a ticket to see Marciano.’ Then I remember Frank Vincent pulling me aside and saying, ‘That Marciano kid…he’s a cowboy. He’s dangerous.’”

With a steady job at the lottery and a positive film review under his belt, Peter focused on politics. In 1993, he’d already run in and won his first election—for a seat on the Brockton School Committee. Six years later, he won a spot on the Brockton City Council, where he served two terms from 1999 to 2003. From the start, Peter’s victories in government were small but impactful. He repaved the streets that Rocky had run along during his early training days, the same ones Peter jogged on as an elite high school and college athlete. He’d finally found his place as a champion of the people, devoted to once again making Brocktonians proud. “He wanted to become mayor of Brockton,” Stephen Marciano says. “He wanted to give back to the city he loved and use it as a launching pad for a run for U.S. Senate.”

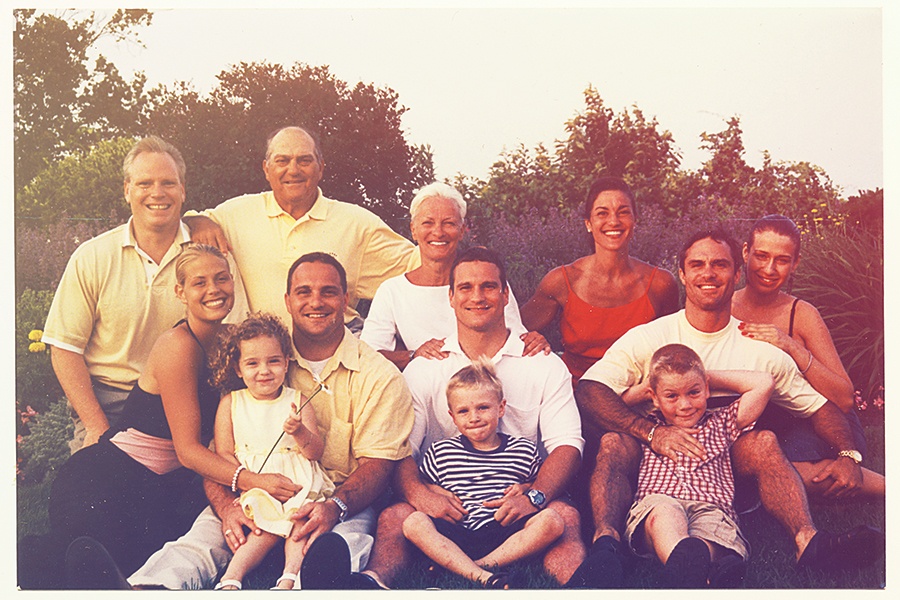

Photo provided

Peter eventually married, started a family, and even began working as a Little League umpire. To the casual observer, he was a dedicated civil servant and a hard-working dad who spent his Sundays at the ball field—the American Dream in action. During Peter’s second city council campaign, though, his brother Stephen, who served as his campaign treasurer, started noticing irregularities. “He’d ask for $100 here and $200 there,” Stephen says. “I didn’t give him any money because I had a bad feeling about where it was going.”

Turned out, Stephen was right. One night in the early aughts, Peter took a ride with a friend down Route 138 in Easton. When the two men stopped along the side of the road, the driver offered Peter a needle full of heroin. Peter accepted—it was his first time. “My brother later told me,” Stephen says, “that he knew at that moment it was all over.”

Peter usually never had much trouble finding drugs. After all, in a relatively tight-knit town like Brockton, the hometown hero knows just about everyone, including the pushers. On one desperate day in 2005, however, he was coming up empty, so Peter drove to South Boston to score. Short on money, he planned to rob a local dealer. He didn’t bring a gun, but he did have his pet German shepherd sitting next to him in the passenger seat.

Slowly cruising the neighborhood’s narrow streets, Peter spotted a dealer. He rolled up on him, grabbed a bag of heroin, and attempted to flee. As the dealer reached back into Marciano’s car for the drugs, the dog lunged at the man, biting his face. In a scene straight out of a Quentin Tarantino movie, Peter sped away with a bloody chunk of the dealer’s ear resting on the passenger seat.

Photo provided

By that point, Peter’s body had begun to deteriorate. While colleagues and friends made excuses for him, no one was blind to his feeble physical condition. “He was emaciated,” Stephen says. “He had gone from one of the most physically gifted people I had ever met, strong and intelligent, to this shell of himself. He started taking steroids and kept working out to hide it, but again, it was just a mask.”

Fearful and ashamed, Peter opened up to his father. “Dad, I started using the needle,” he told Peter Sr. over coffee at a Brockton Dunkin’ Donuts.

“Where do we go from here, Peter?” his father asked.

“Dad, I’m strong enough. I can overcome this,” the son promised.

Peter Marciano Sr. knew this was a lie. “That was the worst day of my life,” he recalls. “I had lost my brother Rocky in a plane crash, but this somehow was worse. I knew there was no place to go from here.”

As Christmas approached in 2015, Peter’s family felt no choice but to show tough love. The former football star couldn’t give up the needle, so Stephen picked up the phone and disinvited Peter and his children to the Marcianos’ annual holiday celebration. “You’re a fucking asshole,” Peter shouted over the phone at Stephen. “I can’t believe you’d do this to me. All I have is my family. I know this is all you. I hope you realize someday what you did.”

“Peter,” Stephen replied, “I just want you to know that I love you and I’m doing this because I love you. This is the only way you are going to get better. Don’t do it for me, do it for your children.”

“Fuck you,” Peter screamed. “I fucking hate you.”

Seething with resentment over getting barred from a major family gathering, Peter still held onto one important family tradition-the next day, he texted his younger brother three words: I love you.

Three days later, on Monday, December 21, 2015, Peter was scheduled to run a bingo event as part of his job for the lottery. Rich Cogliano’s son, Sammy, was an athlete at Brockton High and had planned to help out by babysitting Peter’s two children after school. No one close to Peter knew that he hadn’t been to work in weeks.

Sammy lifted weights after school before heading with a friend to Peter’s house just down the street from Brockton High. At about 5 p.m., he noticed Peter’s car was there with the headlights on. He stood on the porch and knocked on the front door. No answer. Sammy called his dad.

“Uncle Peter’s not here,” Sammy said.

“Go around to the back door,” Cogliano told his son.

Sammy ran toward the rear of the house and peered through a window but didn’t see anything.

“Dad, he’s not here,” Sammy reported.

Then, Sammy’s 6-foot-3 friend hoisted himself up and started through a high kitchen window. Someone was lying face down.

“There’s someone on the kitchen floor,” the friend said.

Cogliano instructed the boys to break down the door.

“Dad,” Sammy asked, “I’m going to go in there and Uncle Pete’s going to be dead, isn’t he?”

The young football player kicked in the door and ran inside. Dressed in sweatpants and a shirt, Peter was lying on the linoleum in a fetal position. Foam formed around his mouth and a pool of spit lay on the floor. A needle, a spoon, and other drug paraphernalia rested on a nearby sink. All Sammy could think to do was rush to Peter’s side, shake him, and scream, “Uncle Peter!”

It’s nearly three years since Peter died, but the bruises are still fresh. When Peter Sr. talks about his son from his living room, a mist begins to form in his eyes. He fidgets with a gold watched strapped tightly across his wrist and pulls it off his arm, laying it across his hand like a jeweler. “This is from the 1986 Rose Bowl,” he says proudly. “Iowa lost to UCLA in that one and my Peter didn’t play in the game because he was red-shirted. But he got this watch like all the other players and he gave it to me, his dad. I’ve had it now for more than 30 years and it’s the only piece of jewelry I wear.” To this day, he says, “I rack my brain constantly thinking about what more we could have done to save him.”

Weeks after Peter’s death, his story emerged as a cautionary tale when 40 people in Brockton overdosed over a two-day spell, casualties in what is now acknowledged as a nationwide opioid epidemic. A month or so later, the city launched its “Champion Plan,” turning the Brockton Police Department into a safe haven for anyone seeking drug treatment without fear of arrest.

Photo provided

At Peter’s funeral, mourners came from Italy and Las Vegas to remember him at Our Lady of Lourdes Church in Brockton. Stephen gave the eulogy. “He was the most genuine, caring soul I ever met,” he told the crowd, “and he cared more about other people than he cared about himself.” Peter’s ashes were split up among his friends and family, but the majority were laid to rest at the family plot in Brockton’s Melrose Cemetery, where Rocky Marciano’s parents are buried, on the same stone memorial honoring the heavyweight champ. The irony is not lost that Peter, dead at 48, just two years older than his famous uncle, was found in his home less than a mile from the 20-foot bronze statue that towers over the town. Peter had fought each day against an opponent more fearsome than any Rocky had ever faced in the ring. “If this can happen to a gifted athlete like my brother Peter, this can happen to anyone,” Stephen says. “Even champions need help.”