The Mayor, the Muckraker, and the Bombshell North of Boston

Everett’s oldest weekly newspaper, the Everett Leader Herald, spent years reporting that the city’s highest-elected official was a corrupt politician who deserved to be thrown in prison. But what if it was fake news?

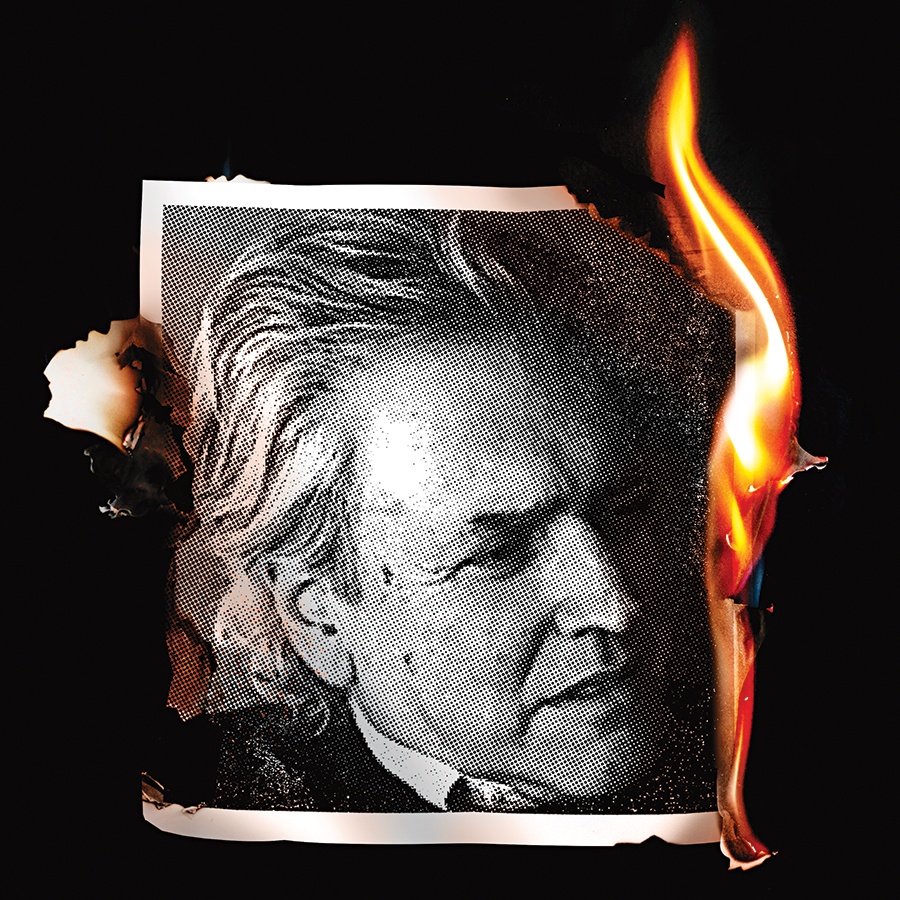

Illustration by Comrade

Every Wednesday for years, Everett mayor Carlo DeMaria woke up with a looming sense of dread.

That was the day, after all, that the Everett Leader Herald hit front stoops and lunch counters throughout the city and people dug in to read the latest news, which was always—almost entirely—about him. And it was never good. Invariably, headlines blared that DeMaria was corrupt, followed by articles, editorials, and opinion columns stating over and over again that he’d demanded payoffs and quid pro quo agreements in exchange for awarding city contracts.

Still, for DeMaria, September 15, 2021, had the whiff of a particularly rotten Wednesday. After kissing his wife, Stacy, goodbye in the morning, he drove the short mile and a half to City Hall, where he had occupied the mayor’s office since 2007, and went up to the third floor to his office. He closed his door and opened the paper.

Splashed across the front page was an article reporting accusations that the mayor had coerced a City Hall employee to give him nearly $100,000 by threatening to ruin the man’s life. A regular column in the paper—which was apparently intended to be satire but wasn’t labeled as such, leading some readers to believe it was based on reporting—outlined a sexual assault complaint against DeMaria by a former employee. The headline read: “Revelations We Cannot Quite Believe About the Mayor…But They Are All True.” DeMaria, the story said, had tried to cut off the blouse of an employee and exposed himself to her. Behind the closed door of his office, DeMaria quietly cried.

He wasn’t the only one shedding tears that day. When DeMaria arrived home in the afternoon, his wife was sobbing and all three of his kids—ranging in age from 11 to 21—were emotional. His wife told her husband that she understood the sexual assault allegations weren’t true, but she was upset because she also knew that people around town would pity her and immediately think she—a stunning woman with flowing red hair framing her face—was a loser to be married to such a monster. Several days later, as his tight-knit Italian family did every Sunday, DeMaria had dinner with his elderly parents. But that week, the meal was anything but friendly. “If this is true,” DeMaria’s father told him about the story in the paper, “I don’t want to have anything to do with you.”

Around town, the reaction was even less charitable, and the constant drumbeat of negative coverage in the paper began to alter the course of DeMaria’s political trajectory. A lifelong Everett resident, he had been in local government since 1994—while still a student at Northeastern University—and is now in his 16th year as mayor of his hometown. For a long time, DeMaria was incredibly popular. In 2017, he ran unopposed, with a favorability rating, he says, higher than 80 percent. His people skills, all the handshaking and backslapping, had always been an asset to secure votes. But during the 2021 campaign, when he canvassed the city to talk to residents, they suddenly began slamming doors in his face. One day, as he went from home to home on Summit Street, his friend’s mother answered her door. DeMaria expected a warm reception. Instead, she looked at him with disgust. “I’m not voting for you,” he says she told him. “I read those articles. You’re a horrible person.” He heard that a lot, especially from older people, who just happen to make up a large chunk of the residents who read newspapers and vote in local elections.

With each withering look and rejection out on the campaign trail, DeMaria could feel the credibility he had enjoyed for years waning. The election was just several weeks away, and he was worried that his long-held grip on the mayor’s office was slipping away. Meanwhile, for Matthew Philbin, who owns the Everett Leader Herald, and Josh Resnek, who writes and edits the paper, that was precisely the plan.

Carlo DeMaria, the long-running mayor of his hometown of Everett and the highest-paid mayor in the state, was repeatedly accused of corruption in the pages of the Everett Leader Herald. / Photo by Nicolaus Czarnecki/MediaNewsGroup/Boston Herald via Getty Images

Everett is a gritty city of some 50,000 souls, densely packed and largely working-class. Residents live alongside scrap metal heaps, industrial monstrosities, and the polluter’s playground known as the Mystic River. The area is also home to newly greened spaces, various eateries, and—rising above it all—the Encore Boston Harbor casino, which opened in 2019 after a $68 million cleanup of close to a million tons of Everett’s chemically contaminated past.

At the same time, it’s also a city run on generational grudges and ethnic tribalism—an entangled web of shifting grievances and alliances informed by inherited animosity and the day’s latest pissing match. As the Boston Globe recently wrote, it’s a place “where certain influential people and their families are viewed as untouchable” and a place that “runs on old friendships and bad blood, a thicket of political alliances controlled by a circle of white political leaders who owe their jobs, their contracts, or their allegiance to the mayor, Carlo DeMaria.”

That mayor, now 50, had presided over unprecedented development during his four terms, during which his salary jumped from $185,000 to $236,647—more than any other mayor in Massachusetts and more than three times the median household income in Everett, where 13 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. That was thanks to an unusual “longevity bonus” of $10,000 a year for each term the mayor had served. His political opponents chafed at the pace of development, and gagged on that salary. “[E]lected officials…get reelected,” sniffed one. “That’s their reward for a job well done.”

The members of the Philbin family, who own the Everett Leader Herald, certainly were not among those who owed their allegiance to DeMaria. Quite the contrary. In fact, when he was a city alderman, DeMaria had voted not to renew the licenses for the family’s boarding houses. (DeMaria defends the move, saying the buildings were non-compliant flophouses rented to “shitbags.”) Nor did the mayor give a city contract to the Philbin’s insurance company—a contract from which the family had collected hundreds of thousands of dollars in the past. DeMaria made it clear that they didn’t run the city anymore.

The Philbins, who declined to comment, decided to fight back—after all, that was the Everett way. And so in 2017, Matthew Philbin and his father, Andy—neither of whom had ever been in newspaper publishing—bought the beloved 100-plus-year-old free, local weekly newspaper, the Everett Leader Herald. Their goal was simple: expose DeMaria for the corrupt public official they said he was.

The Philbins brought on a local scribe named Josh Resnek, whom Matthew had paid $10,000 a decade earlier to do public relations work for a DeMaria political opponent, to write and edit the newly acquired broadsheet. They set up office in a faded-white triple decker at 28 Church Street, enabling Resnek—who sat on dated furnishings among a pile of old newspapers in his cluttered office—to write the paper with its principal target right in his sights: The backside of City Hall was just across the street.

No job at the paper was too small—or too big—for Resnek. He wrote the articles, the “Eye on Everett” editorials, and “The Blue Suit,” his satire column, which only recently began carrying a disclaimer that it wasn’t, in fact, real news. He sold ads and even loaded a good portion of the papers into his red 2006 Honda Fit each Wednesday, personally delivering them to dozens of corner bodegas, retail establishments, and even City Hall itself. The rest of the papers were delivered by, as Resnek put it in an email to a friend, “a bunch of Brazilians and what we used to call the retarded.” Meanwhile, according to Resnek, Philbin didn’t just bankroll the paper; he also looked over all of the articles before they were published, suggested changes, and made edits.

In many ways, Resnek, who is 73 years old and related to a minority owner of Fenway Sports Group, Frank Resnek, was the perfect man for the job. A self-described investigative journalist who had worked at many Boston media outlets during his decades-long career, he was a quirky, bombastic, and cocky wordsmith. But what most qualified him for the job was his fearlessness. Resnek wasn’t afraid of anyone. Especially not DeMaria. “Everyone tries fucking with me,” he explained in an email to a friend. “But they can’t because I fight back, unlike every other voice in this city.”

As with Donald Trump and his “Crooked Hillary,” “Lyin’ Ted,” and “Cheatin’ Obama” monikers, Resnek coined a nickname for the mayor, “Kickback Carlo,” and used it in nearly every story he wrote. He referred to the mayor’s family as the “DCF”—DeMaria Crime Family—and supported “ABC,” Anyone but Carlo. In a September 11, 2019, editorial—in which he repeated the nickname 11 times—Resnek wrote, “Kickback Carlo DeMaria is in his tenth year of organized, obscene, uniquely disguised municipal theft and greed.” It was high time, Resnek wrote, for then–U.S. Attorney Andrew Lelling to take a good look under the hood of City Hall.

In 2012, Steve Wynn (right) joined DeMaria at Everett City Hall for a press conference to discuss preliminary talks regarding the development of what eventually became Encore Boston Harbor casino. / Photo by Bill Greene/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

It was easy copy for the hard-nosed writer to lay down. In emails, Resnek bragged he could write the entire paper in two days, then send it to owner Philbin for his review, revisions, and approval. Such light work at the paper left Resnek time to work on the book manuscript he was coauthoring about DeMaria’s role in bringing the Encore Boston Harbor casino to Everett. Resnek was convinced that DeMaria had a shady hand in the decision to award the gaming license to Steve Wynn instead of Everett native Joe O’Donnell, the Boston business tycoon and famed Harvard donor and Harvard Corporation member, who Resnek considers a friend. Resnek emailed one of his friends that O’Donnell had gotten Resnek’s son, Joe—a former speechwriter for President Barack Obama—into Harvard. (O’Donnell confirmed that he wrote recommendations for Joe Resnek’s applications to both Harvard College and Harvard Law School.) In May 2019, Resnek shared his thoughts on the casino deal with O’Donnell himself, emailing that he thought the casino deal had been rigged. “Remember Joe,” he wrote, “this fat useless fuck so adored in your hometown, is not so unlike you and me. He wants a cut of whatever he does with this money which is not his. Unlike you and me, he is an elected public official.”

Resnek’s day job and his authorial ambitions beautifully interwove. As he tried to drum up interest in his manuscript, he emailed it to a potential publisher at the end of 2020, directing the editor to “pay attention” to his attached news clips, especially one headlined “Court Case About Encore Reveals Secrets,” with the opening line, “Mayor Carlo DeMaria has a passion for backdoor deals pressuring someone to do his bidding.”

When it came to his abilities as a journalist, Resnek didn’t lack confidence. “No one, I repeat NO ONE in community journalism does what I do in the entire United States today,” he wrote to a friend in a 2021 email. In fact, Resnek fancied himself a throwback to the bygone era of the gumshoe reporter. He pounded the pavement, worked the phones, and received a steady stream of chummy local citizens stopping by the office to tell him their secrets.

Still, now in the sunset of his long career, he harbored some regrets—which appeared to fuel his ever-burning ambitions. In a 2019 email, he lamented to his friend that he had spent his early years in neighboring Chelsea “fucking as many women as I could without ever stopping to know who they were” and “never achieved what I thought I really wanted to do…to write and publish a lasting, powerful, eloquent piece of American narrative genius.”

Perhaps the DeMaria book or the body of his journalism aimed at taking down Everett’s powerful, long-running mayor could be that lasting work. But first, he would need to nail the mayor. With characteristic swagger, Resnek had no doubt that he would, in fact, do just that. “He’s had 12 years to build himself up. We’re into our second full year of trying to take him out,” Resnek told his boss, Philbin, in a December 2020 email. “We will crush this guy. We are crushing this guy.”

Josh Resnek, a veteran journalist who serves as editor and writer of the Everett Leader Herald, was on a mission to take down Everett Mayor Carlo DeMaria. / Courtesy photo

It was a balmy Saturday evening in mid-July 2021 when Resnek parked outside a hulking brick building in Malden, strode under the royal-blue canopy that arched over the front walkway, and ducked inside Anthony’s, a local event hall. That night, Fred Capone—one of two people challenging DeMaria in the upcoming September mayoral primary—was holding a fundraiser. By his own admission, Resnek had been to Anthony’s hundreds of times during his newspaper life. That night, though, he wasn’t there strictly as a reporter or to donate money—he was there to raise some of his own.

Philbin appeared to be hemorrhaging cash to keep his newspaper afloat. Eighty percent of the business’s expenses had come out of his own pocket since buying the paper. Now he was millions of dollars in debt and had used up $1,250,000 of his personal credit line. The city wouldn’t advertise in the newspaper and Philbin was convinced that the mayor was strong-arming other businesses not to buy ads, either. The paper desperately needed another revenue stream if it was going to have any chance of taking the mayor down before election day.

Walking into Anthony’s, Resnek found the joint packed with hundreds of people, including some of Everett’s wealthiest residents. He got to work. As he mingled among the crowd, Resnek ingratiated himself with Everett’s elites, doing some serious “ass-kissing,” as he later emailed a friend. His efforts apparently paid off: According to what he told his friend in the email, Resnek managed to secure $5,000 commitments from two of Everett’s richest men to fund operations at the paper over the next six weeks. That money would keep the lights on while Resnek dropped journalistic bombs that were sure to destroy DeMaria’s chances of getting reelected.

This was not the first time that Resnek claims to have collected money from the people who shared his and his boss’s dream of ousting DeMaria. In April, he had written an email to his friend saying, “[Capone] just put up $20,000 for me to deliver the paper from door to door every two weeks until the primary.” A week later, he told the friend via email that he was going to get an extra $1,600 twice a month from a Capone ally to distribute the paper all over the city. “I’m going to bury this fucker,” he wrote of DeMaria. “It has taken almost three years but I’m going to bury him.” And a few days after that, he told his friend that the next day he was going to the Sunshine Café on Main Street at 8 in the morning to meet a friend of Capone’s for breakfast. After the meal, Resnek said he would go outside to Capone’s friend’s Mercedes, where the friend would open the trunk and give Resnek a thick envelope containing $2,000 in $20 bills. Resnek told his friend in the email that the exact same scenario was going to play on repeat every week until the primary. (In an email to Boston, Capone wrote that he has no knowledge of any friend who gave Resnek money on his behalf, and never put up $20,000 for the paper. He later asked us to retract his on-the-record email responses.)

By midsummer, the paper was apparently flush with cash, including the thousands of dollars Resnek claimed to have collected from Capone, as well as $16,000 he planned to collect from three other individuals, whom he called Mr. A, B, and C. That money, Resnek wrote to Matthew Philbin in a late-July strategy memo, would enable them to print extra copies of the paper to be delivered directly to 8,000 homes and still have 2,700 copies dropped off at 40 other locations each week from August 4 through September 15, just days before the primary.

The cooperation with DeMaria’s opponents wasn’t just financial, according to Resnek. He said he also coordinated on a daily basis with Capone and Gerly Adrien, another DeMaria opponent, about his plans to publish damaging articles about the mayor in advance of the primary. (Capone and Adrien both deny this.) It appeared to be a team effort, if an unconventional—and unethical—one for a reporter.

For his part, Resnek delivered on his promise to write bombshell stories about the mayor. On August 25, he published a triple punch, delivered straight to the front steps of hundreds of homes and businesses in Everett. First, he penned an “Eye on Everett” editorial informing readers that “Carlo talks in code about kickbacks on his cell phone or in-person with developers.” A second editorial stated, “The mayor demands to be paid for whatever he does…. He has blurred the line between public service and municipal corruption.” A third piece claimed that the mayor “apparently paid hefty sums to several women who claimed sexual violence and abuse at his hands so that they should keep their mouths shut.”

It was a jam-packed issue teeming with scoops, all of which DeMaria denies. Yet Resnek knew it would pale in comparison to the atomic attack he planned for the eve of the primary—he even knew exactly what that story would be: The real estate deal he discovered in which DeMaria had allegedly shaken down a city employee for almost a hundred grand. It was like a gift. You couldn’t make this stuff up.

Week after week, Resnek delivered on his promise to write bombshell stories about the mayor.

On the morning of September 6, Resnek opened a new email, attached a draft of his soon-to-be-published atomic story, and typed a familiar name into the address bar: Andrea Estes of the Boston Globe. According to Resnek, Estes had been both a friend and colleague for some 30 years, and he was asking her for any advice or comments she could provide. “I KNOW I HAVE THIS RIGHT. BOTTOM LINE – mayor got $96,000 from the city clerk by threatening him,” he typed into his message to Estes. “I think I have this fat fucker. I’ve been working for three years to bring him down.” “Extraordinary!” Estes responded. “But as your lawyer I would tell you you need to ask the clerk to show you the $96,000 check made out to the mayor.”

It’s not clear what Resnek thought about the imperative of laying eyes on that check, but he was ecstatic and believed he finally had the goods to bury DeMaria once and for all—and to publish a story that would rise to the level of a masterpiece. He fired off a barrage of celebratory emails to friends and colleagues. To a friend: “I feel like I’m about to crush the mayor of Everett two weeks before the hotly contested primary.” And to his book coauthor: “If he can withstand the firestorm from this article, he’s Superman…. This is an early iteration of a fucking masterpiece that will bring this fucker down!”

The Everett Leader Herald hit deli counters and front doors on September 8. The main headline read: “$96,000 Forced Payment to Mayor by City Clerk Raises Questions About Extortion Plot: Payment to Mayor Followed Threats Against Cornelio to Cut His Office Budget and to Ruin His Life.” The article was a jaw-dropper, alleging DeMaria was trying to get a cut of a real estate deal he had nothing to do with. Resnek wrote that city clerk Sergio Cornelio alone purchased a piece of property at 43 Corey Street without any involvement from the mayor and that not only did the mayor stifle Cornelio’s plans to develop the property, but when Cornelio sold it, the mayor demanded $96,000 from the proceeds.

Resnek spelled out his tale of DeMaria’s criminal conduct, supported by quotes from Cornelio, including, “[DeMaria] threatened to cut the city clerk’s office budget and place my future in jeopardy if I did not pay him.” Resnek also quoted Cornelio as saying, “The mayor’s behavior toward me was outrageous and illegal. I should not have been threatened by the mayor to make a payment to him for a real estate deal he had nothing to do with” and “I gave up against the weight of his power over me and his threats to ruin me.”

The morning the article was published, Resnek sent a copy to Estes. “I think I’ve got him,” Resnek wrote. “But he’s as bad as a nasty virus. Tough to wipe out. Do what you can. Use me as your roadmap. No one can duck out of this. It is all on the record. Enjoy.”

Estes and her editors seemed interested in the story. Estes emailed Resnek a few days later, telling him she wanted to write an article on the Cornelio affair and asking him if he wanted to chat. “Whatever you need,” Resnek replied two minutes later. “Do you have any docs?” she responded. Cornelio, she wrote, “is supposed to call me later but my editors want me to get the story published before the primary.”

With a deadline handed down by her editors, Estes emailed back and forth with Resnek that day, strategizing on how to get the info she needed. When Estes grew frustrated that Cornelio hadn’t called her back, she asked Resnek to help. Resnek claimed to her that Cornelio was emotionally unstable, suffering from anxiety and depression. “He must be pushed or you will get nothing from him,” Resnek wrote. “He is the holder of all the secrets about the mayor.” Cornelio never gave Estes the interview she wanted, but Resnek was working to secure an interview for her with Cornelio’s mother.

In the following week’s issue of the Everett Leader Herald on September 15, Resnek doubled down with a follow-up article stating that the mayor had tried to oust Cornelio after taking the $96,000 from him related to the real estate deal. Meanwhile, Estes didn’t make her pre-primary deadline, and despite Resnek and Philbin’s media war on DeMaria, the incumbent topped the ticket in the September 21 primary election, securing some 45 percent of the votes. Capone came in second, and the two moved on to the November general election. That meant there was still time to sway voters against DeMaria. Resnek knew the power of getting the Globe to cover the story. It was more important now than ever.

Everett Mayor Carlo DeMaria at a ceremony raising the city’s first Pride Flag in front of City Hall, in honor of Pride Month on June 22, 2020. / Photo by Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

On September 29, 2021, Resnek wrote to Estes with good news: He had finally secured the interview with Cornelio’s mother, Margaret. “I loaded it up nicely,” Resnek relayed to Estes, explaining that he gave Margaret Cornelio a heavily discounted rate for an ad in his paper for her recently announced candidacy for school committee member at-large. “Mrs. Cornelio’s 1/4 page thank you helped things along.” About a week earlier, Resnek had emailed Philbin to inform him of the arrangement. “I have taken care of Mrs. Cornelio as suggested/directed. All Set.”

Estes did not decline the interview, despite Resnek having told her it had been secured through what amounts to a payment to the interview subject, a practice considered unethical and frowned upon in most journalism circles. Estes said in an email to Boston that she didn’t remember seeing Resnek’s email and pointed out that she didn’t use material from the interview in any story. In an email to Boston magazine, Globe editor Brian McGrory said the paper had completed a review of its Everett coverage and found “no issues of fact or concerns about origin in anything we’ve published.”

In any case, Resnek joined Estes for her interview with Cornelio’s mother. Cornelio’s father attended, too. The group met at the since-closed Dockside on Centre Street in Malden at 2:30 p.m. on September 30, 2021. Following the interview, Resnek emailed his friend about it. “Met with Andrea Estes and my people for two hours. It was a five star interview for Andrea,” he typed, adding that he found her attractive. “I suggested her coming magnum opus could be a fait accompli for Carlo DeMaria. What a great thing happened this afternoon, the beginning of the end for a corrupt small city American mayor.” Resnek also updated his coauthor on the book project, emailing that he was close to getting the mayor indicted and when it came to selling their book, that would “benefit both of us big time.”

Estes’s article didn’t appear in the Globe until October 29, four days before the election. Even though Estes had apparently spent two hours interviewing Cornelio’s parents, she did not quote them in the piece. She didn’t need to, because papers that had just been filed in court outlined all of the allegations that Resnek had written about: that the mayor, despite not being involved in the purchase or development plans for the property, forced Cornelio to give him 45 percent of the proceeds of the sale. Estes also brought up allegations from a 2014 Globe story about the mayor’s alleged “unwanted advances” on four women, without mentioning that three of the women had never filed charges against him and that the one who did—nearly 20 years ago—had her complaint dismissed by the court after finding no probable cause. “He has survived,” Estes wrote, “but some observers say this latest controversy could hurt him in Tuesday’s election.” Now, the accusations against DeMaria had reached a much larger audience. Suddenly, all of Boston and New England knew.

The impact of Estes’s coverage was not lost on Resnek—he was over the moon. On Sunday, two days before the general election, Resnek emailed a coworker: “I’m sure you saw the Globe piece on corruption in Everett! Pulling that off with Andrea is a big deal so close to the election. Put up the Globe article on our website and on Facebook right away.”

On election day, voters across Everett streamed into voting booths to cast their ballot for mayor. After the polls closed and the votes were tallied, DeMaria, his wife, and their three children climbed into the car to head over to Orsogna Plaza, a squat brick bulwark on Main Street wedged between Sebastian’s Unisex Salon and Henry’s Auto School, where 300 of DeMaria’s supporters had gathered to watch the election results roll in.

DeMaria won. Barely. With just 51 percent—or 210 more votes than Capone—of the 7,300 cast, it felt like a loss to the mayor. As he and his family made their way there, his wife and children cried in the car. It had been a brutal campaign, on all of them. They had been publicly shamed, and it stung. So that night, standing before a crowd of supporters, DeMaria lost control of his emotions as the words tumbled out of his mouth. Instead of talking about the path forward for Everett, he spoke of revenge. There were people “who tried to sandbag us in the days before the primary and the days before the general election,” he said in his thick Massachusetts accent. “It hurt us, but in the long run, it’s going to hurt them.” It was to Resnek and the Philbin family that the mayor directed his remarks that night. “Let me tell you—I raised a lot of money, and I’m going to go after a lot of people,” he said. “My focus will be on that.”

In fact, he was already focused on it. Two weeks after the primary, DeMaria had filed a defamation lawsuit in Middlesex Superior Court alleging that the Everett Leader Herald had engaged in a vicious campaign full of “malicious and outrageous publications of defamatory falsehoods” against him.

As part of the lawsuit, over the course of four days this past summer, Resnek, dressed in a suit, his white hair wild, his bushy beard full, made his way into a brick building near Copley Square, went up to the fifth floor, and took a seat at a long conference table, where DeMaria’s lawyer deposed him under oath. As the days wore on, Resnek grew progressively more fidgety and manic. He constantly interrupted and cut off the lawyer questioning him and was frequently reproached by his own lawyer. Still, what came out of his mouth over the course of those few days was the biggest bombshell yet about the mayor. In fact, it might just be the biggest bombshell of Resnek’s entire career. Under oath, he confessed that his body of reporting on the mayor was as likely to be fiction as fact. He admitted that he’d published lies.

With the Globe article, the accusations against DeMaria had reached a much larger audience. Suddenly, all of Boston and New England knew.

During his deposition, Resnek sealed his legacy: not that of a fearless journalist but of a fabulist. He admitted that he’d found no evidence of DeMaria receiving a kickback for the Encore casino deal in Everett, even though he’d reported in the paper that he had. Resnek claimed he was merely expressing his “opinion.” Resnek also confessed that he had made up all the quotes attributed to Cornelio in his explosive September articles about the Corey Street deal. Every single one of them. Resnek failed to conduct even the most basic journalistic efforts to determine whether there was a formal agreement between Cornelio and DeMaria. In fact, a judge had issued a written opinion that Cornelio and DeMaria did act together in the purchase, development, and sale of the property, and DeMaria had obtained an advisory opinion from the state ethics commission concerning his interest in acquiring a financial stake in commercially zoned land in Everett. DeMaria also filed a “Disclosure of Appearance of Conflict of Interest” with the City Clerk’s Office for his ownership interest in a property adjacent to Everett Square. Resnek owned up to the fact that he’d never checked for these documents.

What’s more, Resnek never got a word out of Cornelio when he “interviewed” him, let alone the damning quotes he published in the article. Yes, Cornelio was convinced that DeMaria did him wrong on the real estate deal. And he had filed a countersuit against the mayor—after Resnek’s articles came out and after DeMaria included him in his lawsuit against the paper—but he himself never talked to Resnek about the topic or provided the quotes attributed to him in Resnek’s story. What actually happened, Cornelio said under oath during a deposition, was that Resnek went to his office with a bundle of newspapers under his arm and berated him for six minutes, voice raised. “Mr. Resnek informed me that he knew that the Mayor extorted me… and I need to grow a set of balls and go fight the mayor,” Cornelio said. “That the mayor, you know, is a bully, and you have to take down a bully.” Cornelio basically stayed silent, and Resnek never asked him a single question. Cornelio said Resnek announced something to the effect of, “It doesn’t matter, I’m writing it anyway,” before leaving his office. (Through his lawyer, Cornelio declined to comment on the Corey Street property. The lawyer, however, did say that Cornelio purchased and assumed all expenses for the property himself.)

During Resnek’s deposition, DeMaria’s lawyer asked him if it was unethical to present speculation as fact, make up quotes, and falsify information about people, as Resnek admitted he had done. Resnek’s reply: It “depends on who you are writing about.”

Resnek proved that he wasn’t afraid to lie to his readers or his fellow reporters. He wasn’t even afraid to lie to the court: He withheld some 125,000 pages of documents a judge ordered him to submit, claiming in an affidavit that they contained confidential sources. Turns out they did not. In fact, so-called “confidential source 14” was none other than Andrea Estes.

Those weren’t Resnek’s only falsehoods. He also lied under oath when he said he had submitted to the court the interview notes supporting the claims in his articles about Cornelio. Under examination at his deposition, Resnek first admitted he had altered the notes after he was sued. Then he admitted that even that was a lie: He’d created his notes after he was subpoenaed in the lawsuit and only then gave them to his lawyers to be submitted as evidence. There were never any real notes at all. Resnek also appears to have lied under oath at his deposition—twice—when he claimed that Cornelio was present during Estes’s interview with Cornelio’s parents. Estes said that was not true. In fact, Resnek has lied so mind-bogglingly often and about so many things it’s hard not to wonder whether any of his confessions to lying are not also lies as well.

It turns out that Resnek may have been deceiving his friends, too. In a back-and-forth exchange with DeMaria’s attorney, under oath, Resnek admitted that those emails about receiving money or promises of money from Capone and his supporters—the envelope of cash, the bi-weekly deposits—were not true. Moments later, he tried to walk back his statement. Resnek declined to comment for this story, so it’s impossible to know whether he lied, or lied about lying.

What’s more, Resnek’s deposition suggests that he hasn’t just misrepresented the truth about the mayor but also about himself, too. Resnek’s glowing résumé and bio didn’t necessarily tell the full story. During his deposition, it came out that the self-described investigative reporter had been terminated several times throughout his career. He was at the Boston Herald for seven months until the paper let him go. Regan Communications fired him almost immediately after he started working there. (Regan represents DeMaria and Boston magazine.) He has done freelance work for the Globe, though not in the past decade. He was forced out of the Independent Newspaper Group—which publishes hyperlocal papers in the Boston area and in which he had an ownership stake—for breach of fiduciary duties. And when he signed on with the Everett Leader Herald, he had just obtained his second discharge from bankruptcy.

Resnek still writes the Everett Leader Herald, but his book project—what was to be his shot at journalistic genius—has been abandoned.

During Resnek’s deposition, as he admitted to lies and fictions, the lawyer interrogating him read aloud a passage from one of Resnek’s masterpieces: a scene in which Resnek reveals that “Kickback Carlo” took money under the table for the casino development, and he, Resnek, implores the U.S. attorney to arrest the mayor once and for all. Upon hearing his own words read back to him, the editor of the newspaper simply said, “It’s beautiful.”

First published in the print version of the February 2023 issue with the headline, “Bombshell.”