The Police Shooting that Boston Forgot

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Photo by Sean Gladwell/Getty Images

When he arrived at Boston City Hospital on the morning of March 7, 1970, though, Lynch seemed lost. Just weeks after the release of his debut single, “Young Girl,” he’d been brought in with a busted shoulder—separated, the nurses thought. And yet for hours, he refused to let them near it, even as his behavior grew increasingly erratic. When he was officially admitted and traded his street clothes for a hospital johnny, a nurse asked him why he wore a watch with nothing inside the glass. Lynch told her he had the special ability to tell time from an invisible clock. Once settled, he refused painkillers and instead asked for Bengay and ice cream. One nurse described him wandering around the hospital interviewing patients, pulling tools off surgical carts, and spitting in wastebaskets.

Hit play to listen to Franklin Lynch’s “Young Girl” and more of Boston’s funk and soul music from the 1960s and early 1970s, curated by Eli “Paperboy” Reed.

Finally, in the early afternoon, he allowed doctors to perform surgery on his shoulder, and when he awoke from general anesthesia, he found his arm set in a heavy cast, twisted uncomfortably in a sling behind his back. Shortly after he was revived, a nurse found him in the bathroom, using his one good arm to run a shoe under a faucet, water spilling onto the floor. When she asked what he was doing, he told her he was washing his shoes.

By the time Lynch was moved to Surgical Ward 2—two intersecting corridors with 24 other patients recovering in beds separated by a thin sheet or simply left out in the open—around 3:30 p.m., BCH psychologists had twice been summoned to examine him because of his bizarre behavior, and guards employed by the hospital had been watching him carefully all day. This was not particularly unusual—another patient, a white man named John Condon, had also “been acting strangely all day,” according to one nurse, who suggested Condon be seen by the hospital’s psychiatric service.

Among the other patients in BCH’s Surgical Ward 2 that day was Abdullah Hassan, who was being guarded by Boston Police Patrolman Walter Duggan; Hassan was recovering from a knife wound sustained during an alleged robbery. Around 5:30 p.m.—dinnertime for the patients—Lynch was clowning around the ward, picking up other patients’ charts and pretending to read them as if he were a doctor. Condon, the patient who’d been observed behaving erratically, got up from a seat near a window and followed Lynch, chirping at him. The two had strong enough words that Duggan came over to separate them. Afterward, Duggan walked Condon back to his bed. Duggan’s prisoner, Hassan, was in a bed just a few yards away.

A bit later, Lynch was annoying a nurse by again pretending to be a doctor—this time, counting the pans in her pushcart. When she asked him to stop, Lynch tried to push the cart out of the room, at which point Condon came back and squared off to fight Lynch, who took a hand towel from over his shoulder and swung it at Condon. Duggan barged into the confrontation and shoved the men away from each other, pushing Condon so hard that he fell and broke his leg. By chance, legendary Boston Globe reporter Robert Anglin was lying in a recovery bed in the ward, intently watching the scene unfold. He described what happened next:

Duggan then pushed Lynch, turned half around facing away from him, drew his pistol and raised it to eyelevel. He aimed it down one end of the ward out of my sight. [Importantly, Anglin is describing Duggan pointing his gun toward Hassan, the prisoner, who had stepped away from his hospital bed.] “Get back or I’ll shoot,” he said. The gun was not yet pointed in Lynch’s direction.

[Duggan] let his gun hand drop— still rigid—and made a quarter turn toward Lynch.

Lynch took a swipe at the gun with his towel and Duggan raised the weapon and fired once, then three times, then once again.

Lynch didn’t move at all when the first shots hit.

After the last shot, he collapsed in a pool of blood.

Patients and hospital staff looked on, aghast. Another man in the ward— 61-year-old Edward Crowley, the father of a Boston Police crime lab photographer—was hit by one of Duggan’s errant shots. “Christ, one of those bullets went right through me,” Crowley exclaimed. He died 11 days later from his injuries.

Just after the shooting, a nurse attempted to attend to Lynch, but Duggan, gun still drawn, screamed at her to keep away. The nurse told Duggan she thought Lynch was dead, but Duggan insisted that the motionless figure lying in a pool of blood was still, somehow, dangerous. Minutes later, a cyclone of doctors and police officers roared into the ward. Lynch was pronounced dead at 6:05 p.m.

Even in 1970, Lynch’s death was so shocking, so appalling, it seemed inconceivable that justice would not be served. There were, of course, no cell phones or security cameras in 1970, but Anglin’s moment-by-moment account—published, complete with a hand-drawn diagram, in the next day’s Globe—was the next best thing, and his version of events was confirmed by multiple eyewitnesses. Lynch’s wanton and reckless killing seemed to be as clear-cut a case of police misconduct as had ever been seen in Boston.

What happened next—a police cover-up, a racist judge’s shocking ruling, the creation by Boston’s Black community of a new forum for justice, and, decades later, the reemergence of Lynch’s killer—is a parable about the insidious resilience of institutional racism in Boston. When we say Frank Lynch’s name, we should first remember the singer and his song—the depth of what was lost—but we should also recall how his killing revealed, and in some ways continues to reveal, an architecture of white supremacy that persisted in Boston long after Lynch’s name had been erased from our cultural memory.

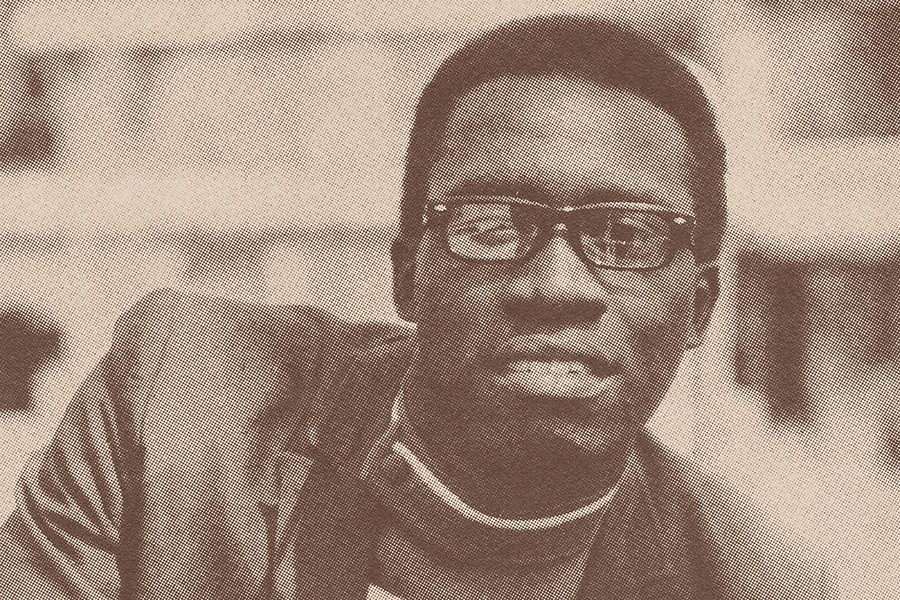

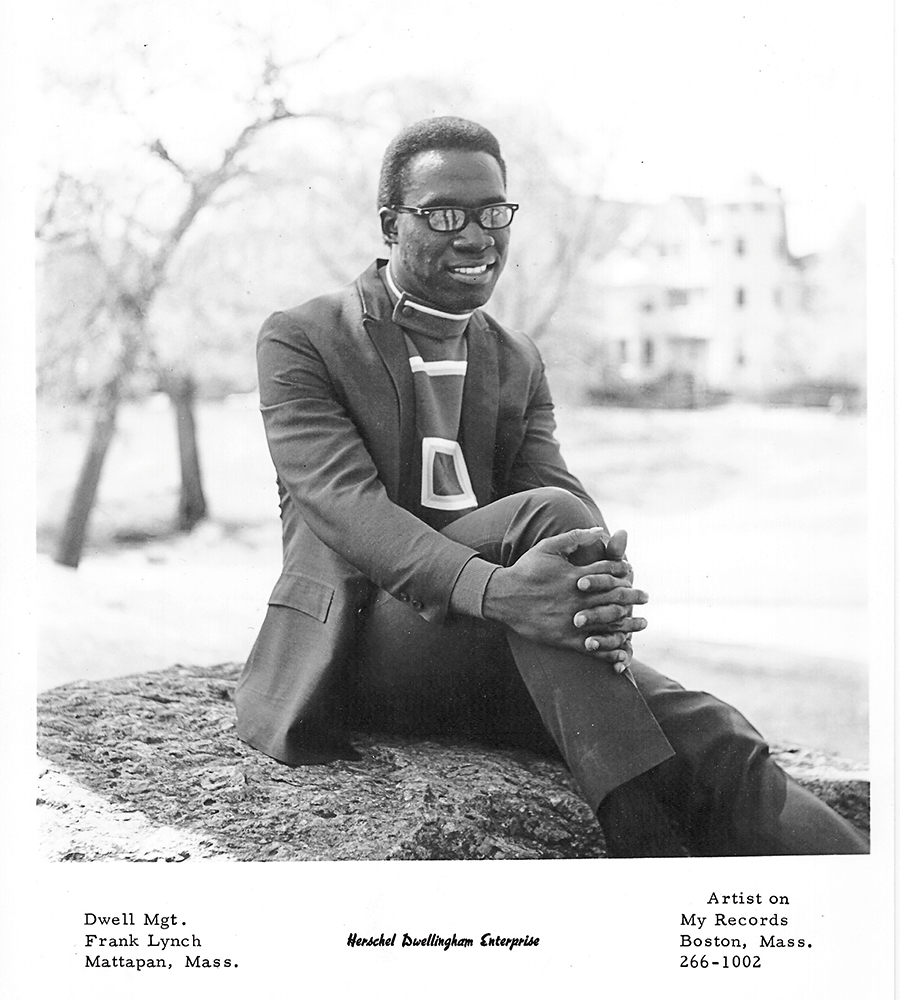

Photo courtesy of Herschel Dwellingham

You can ask anyone who was around back then: In early 1970, “Young Girl” was going to be a hit. The song was written by Dwellingham, who had moved to Boston from Bogalusa, Louisiana, to attend the Berklee College of Music as a teenager and was soon splitting his time between arranging sessions at Boston’s legendary Ace Recording Studios and leading the house band at the city’s hottest soul club, the Sugar Shack. Lynch wasn’t a Boston native, either. He’d been raised in Georgia and New Jersey, and though he began singing at an early age— his favorite song was “Lucky Old Sun”—he hadn’t graduated to performing publicly until he arrived in Roxbury in the mid-’60s. Lynch’s nephew, Joe Nipper, was just four years old when he first performed with his uncle onstage at the Strand Theater in Dorchester—but remembers with awe how Lynch transformed in front of an audience.

Before Dwellingham and Lynch arrived in Boston, there was almost no homegrown soul scene to speak of. But it was the perfect time to build one. They came from a segregated South to find a segregated Boston—one where the recent arrivals were looked down upon, even by some Brahmin elements in the Black community. Out of that tension, Dwellingham began to create something intensely beautiful, melding deep southern soul with an unmistakably northeastern, uptown sensibility. He’d honed his skills on other people’s records and other people’s labels, but by 1969 he felt he’d put all of the elements together: He’d written the perfect song, he had the perfect singer—and he decided to put his own money on the line.

In the summer of 1969, Dwellingham booked a session at Great Northern Studio in Maynard—later home to sessions by the Cars and Aerosmith—and recorded the songs that became Lynch’s debut single: “Young Girl,” backed with “People Will Make You Say Things.” Within weeks of its release, “Young Girl” was—according to Dwellingham and his business partner, Skippy White— climbing the charts in cities up and down the East Coast, and getting rave reviews in the trade magazines. Then tragedy struck. “I mean, here I had the biggest record in the country,” Dwellingham recalled recently, “and all of a sudden the man is dead!”

I first came across Frank Lynch’s story five years ago, in the aftermath of another tragedy: the police killing of Eric Garner, who was choked to death while beseeching his killer, “I can’t breathe.” Not long after Garner’s killing, I met up with Eli “Paperboy” Reed, a soul singer originally from Brookline who’d recorded “Young Girl” for his 2010 major label debut. Reed mentioned that Lynch had been killed soon after recording the song. Somewhere along the line, Reed and I decided that Lynch’s story needed a wider hearing, and we resolved to do what we could to find out what had happened to him. Reed would use his music industry connections to contact the people who’d worked with Lynch, and I’d dig into newspaper and court archives to learn what I could about the shooting.

But the idea ended up on the back burner until this past summer, when—once again—it felt like the world needed to hear Lynch’s story. In June, as thousands of Bostonians joined peaceful protests to seek justice for George Floyd, I often thought about Lynch’s shooting—about the structural racism that prevented his killer from being prosecuted in 1970, and about the resilience of systemic oppression, how it has persisted despite decades of community resistance.

One of the things that made Lynch’s killing different from previous police shootings was that a major player in Boston stepped up to plead for justice. While the BPD issued a statement the day after the slaying claiming it was justified because Duggan was “acting in the performance of his duty,” leaders of Boston City Hospital quickly went the other way. One trustee went so far as to call the shooting a “dispiriting catastrophe.” So enraged were the trustees that they took two extraordinary and controversial steps: Breaking with city protocol, they publicly called on Boston Mayor Kevin White to suspend Duggan from the police force—a clear sign they believed the officer was at fault. Furthermore, they immediately banned armed guards, including the police, from the hospital.

The reality was that an armed policeman should never have had any interaction with Lynch in the first place, according to the hospital. The reasons for this policy were apparent in Lynch’s stay at BCH. Hospital guards were accustomed to handling patients with mental illnesses, and they’d been managing Lynch’s behavior all day—even when he reportedly threatened a guard with a pair of surgical shears. However, a nurse in the surgical ward briefly left the floor and asked Duggan to look after Lynch—an action that the hospital regarded as a tragic mistake. (According to BCH’s director, the nurse resigned after the shooting.)

The hospital’s call for Duggan’s ouster set off a nasty, public showdown with the city’s powerful police commissioner, Ed McNamara, who accused BCH leadership of “making a scapegoat out of a police officer,” and instead blamed the shooting on the hospital’s “administrative failure .” Presiding over an emergency meeting on March 18, BCH board of trustees chairman David Nelson said he wasn’t sure the hospital’s statement had been the “proper thing to say,” but he spoke out because he feared that nothing would be done about the incident.

Nelson had reason to be concerned. When BCH ordered a full report on the Lynch shooting on March 11, he got a call from the mayor’s chief of staff, Barney Frank, the very next day, ordering an end to the investigation. After the board indicated its intention to press on anyway, the hospital’s lawyer passed along a warning from Assistant District Attorney Lawrence Cameron that BCH should not take any statements from witnesses regarding the incident. This left the hospital in an impossible situation: If it wanted to conduct an independent investigation into a shooting on its own property involving its own employees, it would have to do so without interviewing those employees and would be doing so in defiance of City Hall.

There was every reason to suspect City Hall would simply back the police; that’s how it had always been done. Frank said as much in his 2015 memoir, Frank: A Life in Politics from the Great Society to Same-Sex Marriage. While he didn’t write about the Lynch case specifically, he addressed his relationship with the police during his time in White’s administration: “My experience was that if I presented a plausible case of police misconduct, especially if I could identify the officers involved,” Frank wrote, “the department would investigate, report back to me that nothing untoward had occurred, but privately reprimand those involved and order them not to repeat the behavior.”

By early April, tensions were starting to boil over. A meeting between Police Commissioner McNamara and John Gracey, the BCH administrator, did little to repair the rift between the BPD and the hospital. It didn’t help that around the same time, 130 BCH physicians signed a petition “deplor[ing] the shooting by a City of Boston policeman” and supporting the board of trustees in calling for Duggan’s suspension. On April 5, activists and physicians marched from Dudley Square to the hospital, holding signs reading, “Compensate Lynch’s Family” and “Avenge Frank Now.”

In retrospect, this was one of the last times that it appeared Lynch’s killing would produce justice. Because at that moment, there was pressure building on the city and the police from well beyond Boston City Hospital. A week after the shooting, as Lynch was laid to rest, 16 Black community organizations in Boston had demanded an external investigation, and the NAACP had called the U.S. Department of Justice to request a federal inquiry. Not long after that, both of Massachusetts’ U.S. senators—Democrat Ted Kennedy and Republican Edward Brooke, the first Black man elected to the Senate—announced that the FBI would undertake a “thorough investigation” of Lynch’s killing. Other investigations were reportedly under way as well—by the attorney general’s office, the district attorney’s office, and the BPD’s own homicide squad—but the FBI’s investigation, under the auspices of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, would have superseded all of them.

But that’s not what happened. It’s important to think about this juncture, because when we seek to understand the frustration that has led to our current moment, we need to internalize the decades of instances when the institutions that are supposed to protect us equally did not. In April 1970, that occurred in one fell swoop, when all of the agencies looking into Lynch’s killing were preempted by a request from the Suffolk County medical examiner for a Boston Municipal Court inquest—a clever end-around that landed the investigation, and the sole decision of whether to charge Duggan, in the courtroom of a notoriously nefarious judge.

A promising young soul singer, Franklin Lynch moved to Roxbury in the mid-’60s. / Photo courtesy of Herschel Dwellingham

Judge Elijah Adlow was, literally, from another century. Upon his retirement, at 76, in 1973, after some 45 years on the bench, the New Yorker wrote that the judge “had probably disposed of as many criminal matters, and criminals, as any man alive.” Charismatic, flamboyant, and vain, Adlow was born in 1896 in the West End; attended Harvard and Harvard Law; served in the Navy during World War I and the National Guard through World War II; was elected to the state House of Representatives; and was appointed a Special Justice of Boston’s municipal court—all before 1950. Adlow spoke and wrote widely, self-publishing several books and contributing articles for magazines such as the Atlantic Monthly and the Nation. As the New Yorker wrote, he was known to reporters as an easy human-interest story on a slow news day: a “dispenser of a kind of rough, old-fashioned justice” who’d spout one-liners from the bench.

The flip side of Adlow’s populist charm was his vicious approach to raw judicial power: One Boston lawyer said at the time that Adlow’s “lawbook contains no Constitution, no rules of evidence, no legal niceties like presumption of innocence or due process.” Charles Dattola, a Boston attorney who helped represent Lynch’s family in a subsequent civil trial, put it more directly: “Adlow,” he told me, “was a stone-cold racist.”

It was wildly uncharacteristic for Adlow to delay a hearing. But as pressure mounted for Duggan’s suspension, the judge gave a wounded Boston Police Department the one thing it most needed to escape the stink of injustice: time. Adlow pushed back the municipal court’s inquest for more than a month, and that crucial delay allowed the BPD to insinuate false narratives into the press.

The Boston Globe, accustomed to taking police statements at face value, often reported the BPD’s claims credulously—even when those reports contradicted Anglin’s eyewitness account. Suddenly, Lynch hadn’t swung a towel once at Duggan—now, the Globe reported, Lynch had been “attempting to disarm” Duggan. It didn’t make sense that Lynch could “disarm” an officer with a towel, so the police claimed—and the Globe reported—that Lynch had somehow managed, with one arm tied behind his back, to lodge a metal clipboard in the orange hand towel draped over his shoulder and strike repeatedly at Duggan. Anglin was clear that Duggan had given one warning—to Hassan, the prisoner—but now the Globe was reporting the BPD contention that Lynch had ignored “several warnings” from the officer. And despite Anglin’s eyewitness testimony that Duggan had shoved Condon to the floor hard enough to break his leg, and pushed Lynch away, the Globe reported that Lynch had “lunged” at Duggan, “knocking him backwards.”

The problem for the BPD, and for Adlow, was that none of this made Lynch’s shooting any more defensible. Even with the outright falsehoods introduced into the narrative, there was still no justification for shooting an unarmed civilian, much less an officer discharging his weapon five times in the middle of a crowded hospital ward. And so Adlow’s decision to absolve Duggan of blame in Lynch’s killing became a landmark of institutional racism in Boston.

First, it’s worth noting what Adlow found to be true about Lynch’s killing. In his official report, the judge repeated the claim that Lynch had struck Duggan with a metal clipboard wrapped in a towel. This time, the Globe noticed the discrepancy with previous eyewitness accounts, and asked Adlow about it. Adlow admitted, according to the Globe, “that all the witnesses to the incident concurred with this account [that Lynch had only a towel, no clipboard] except Duggan.” A subsequent Globe editorial confirmed that, according to Adlow’s report, eight independent witnesses—“six patients, a nurse and a nurse’s aide”—refuted Duggan’s clipboard story. All of which means we know two things to be true: Duggan lied about the clipboard, and Adlow knowingly repeated the lie in the official finding.

Equally as important, even Adlow’s report contradicted numerous police claims that Hassan, the prisoner, had charged at Duggan. According to all of the eyewitnesses with a view of Hassan, as Duggan was breaking up the tussle between Lynch and Condon, Hassan got out of his hospital bed and moved in the direction of the exit. “Duggan began to back up so as to cover the door, and drew his gun and pointed it at Hassan, ordering him back into bed,” wrote a Bay State Banner reporter in summarizing Adlow’s report. By some accounts, Hassan complied. That’s when Duggan shot Lynch.

In nearly any court of law, this set of facts would likely be enough to send the officer to jail. But Adlow invented a troublesome reasoning to set Duggan free. When Duggan raised his gun and Hassan did not immediately return to his bed, the judge wrote, “the actual firing of the gun by Officer Duggan was justified in order to impress upon all the futility of what was being attempted.” To underscore the ruling: Adlow said the police were justified in shooting an unarmed Black man to make an example of a different unarmed Black man who an officer thought might be trying to escape.

If that wasn’t enough, Adlow added another justification: If Duggan had failed in his “duty” to prevent Hassan from escaping, “he stood to be a discredited man in the Police Department.” That’s not a typo: A Boston judge in 1970 ruled that a police officer was justified in killing a Black man because that officer could not stand to be embarrassed.

The inquest was closed to the press and the public, and Adlow’s final report was impounded. So while parts of the inquest report leaked to the press, the full 17-page document was officially a secret. Shortly thereafter, Lynch’s family brought a civil suit against Duggan and the city in federal court. In 1973, an all-white jury found Duggan not responsible for Lynch’s death.

As I searched for the civil case and read news clips of the time, though, I also began to notice references to a different type of investigation that had taken place. When it began to look like justice wouldn’t be served back in the spring of 1970, the Boston Black United Front, the Black Lives Matter of its day, came up with a new idea: If the city or the country wouldn’t bring charges against this officer and put him on trial, well, maybe the community could.

“Hear ye, hear ye, hear ye: All persons having anything to do before the honorable, the justice of the Black people’s court will now draw near, give their attendance and they shall be heard. May the Black gods of justice save the Black people of the world.”

It had rained hard, and now, as Judge Cameron Byrd gaveled the people’s trial to order on a Thursday evening in April 1970, it was hot and miserable inside the makeshift courtroom at Crown Manor on Warren Street in Grove Hall, where 700 people had packed themselves into a building that once housed a synagogue and a kosher catering company. “This will be the first time in the history of Boston’s Black community,” LeRoy Boston, the cochairman of the Boston Black United Front, had said in announcing the court, “that a community trial has been used to bring justice for the death of a Black man.”

The United Front hatched the idea for the trial shortly after Lynch’s shooting, when it became apparent the police wouldn’t suspend Duggan. But the idea of the Black community creating its own system of laws—outside of a white-controlled justice system that disenfranchised Black citizens at every turn—had been building for years. The United Front was formed as an umbrella organization whose members included dozens of Black community groups across the ideological spectrum, from the Panthers to the NAACP. But the coalition broke down just days after it was ratified, when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April 1968. The NAACP attempted to work with City Hall to calm tensions, while the United Front—with financial backing from wealthy white suburban liberals—pressed for deeper structural change. As J. Anthony Lukas wrote in Common Ground, his indispensable history of Boston’s desegregation crisis, the United Front outraged Boston’s political and financial power structure because “it involved—both as donors and as recipients—volatile new forces in the community who wouldn’t play by the old rules; and because it threatened established institutional relationships.”

Now, in the spring of 1970, Lynch’s shooting was deepening those fissures. Mayor White was often described as a progressive—reactionary South Boston whites had nicknamed him “Mayor Black”—but his refusal to act in the wake of Lynch’s killing shattered his relationship with the Black community. Black leaders including Reginald Eaves, head of the mayor’s own office of human rights, excoriated him for failing to stand up to the police department, allowing the official inquest to drag on, and for not showing his face in Roxbury during the crisis.

It was against this backdrop of dissembling and inaction that the United Front announced a new forum for Black justice: It would put Patrolman Walter Duggan on trial for murder. Reading about the trial nearly a half-century later, at the dawn of the Black Lives Matter movement, the idea resonated with me: It echoes down to us now in our own time. Now, whenever I hear Cornel West say that justice is what love looks like in public, the United Front’s community trial is the first thing I think of.

At the time, though, the trial was controversial—even in the Black community. Some letter-writers to the Bay State Banner, even those who saw Lynch’s killing as an act of racism, said they thought the idea was silly. Herbert Lee, a bandleader who performed with Lynch, told one rally crowd that “mock trials” wouldn’t solve anything: “Justice will only prevail,” he said, “when masses of people confront those responsible for this crime and demand it.”

In the weeks leading up to the community trial, invitations were sent to the police commissioner, the mayor, BCH leadership, the district attorney, and others. The Front wrote a letter inviting Duggan to present his own defense. Predictably, almost none of the invited guests came. In the stifling heat inside Crown Manor, hundreds of onlookers heard Anglin’s Globe article read into evidence. There was a reenactment of the shooting, which the late Boston politician and activist Chuck Turner described to me in 2015 as “a Greek pageant play.” Sure, it was a show trial, but members of the United Front marveled that the audience listened seriously and with intent. At one point there was a disturbance in the room, but someone shouted, “Respect the court!” and order was restored.

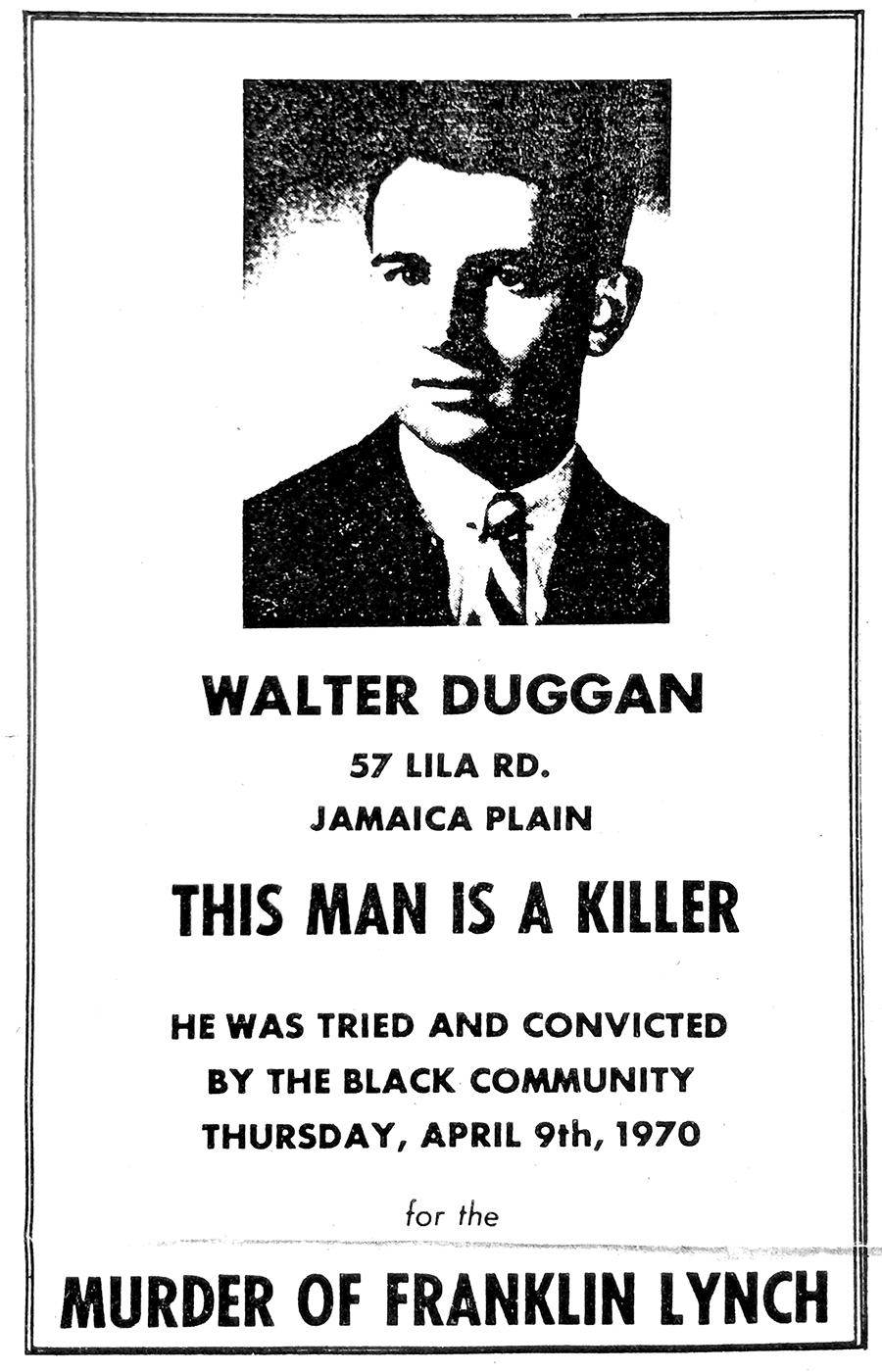

Though the outcome was never really in question, Duggan was convicted of murder by a unanimous vote of the assembled members of the Black community. The sentence, which the United Front had prepared in advance, employed a tactic that was just beginning to emerge in activist communities across the country but had never been used in this way before—today, we might say they doxxed him. The United Front printed up 10,000 posters with Duggan’s name and high school yearbook photo on them, along with his address. “THIS MAN IS A KILLER,” it read. “He was tried and convicted by the black community for the murder of Franklin Lynch.” As the trial concluded, Judge Byrd addressed the assembled throng. Duggan’s “picture is in your hands,” he said. “Look at it. The destiny of this man is in your hands.”

The posters were displayed all over Boston, even after (according to the United Front) police officers harassed businesses that put them up. In 2006, United Front chief of staff Lenny Durant told an interviewer that the campaign had been a success. “The outcome of that was that the policeman—he left the force, left the town, moved away.”

As it turns out, that’s not what happened to Duggan. He stayed at the BPD, and was eventually promoted to sergeant detective. According to police records, Duggan retired from the force in 2003—but not before the department found one more way to assault Boston’s Black community with the memory of Lynch’s killing.

Never convicted of a crime, BPD officer Walter Duggan appeared on a poster following a community trail.

In the mid-’70s, after Judge Arthur Garrity’s landmark decision to desegregate Boston’s public schools, the city was ravaged by white mobs seeking to keep Black people out of their neighborhoods. The BPD unit charged with protecting Blacks against white violence, the Tactical Patrol Force (TPF), made no secret of siding with the townies, even in the face of getting stoned and jumped by whites in Southie and Charlestown. TPF was deeply loyal to the Boston Police Patrolman’s Association, which had argued that the police could refuse to enforce Garrity’s desegregation order. In 1976, the New York Times reported that Boston Police had made 937 arrests in the battle to desegregate the schools—but “not a single one of those arrested has spent a day in jail.”

In 1978, future Boston Police Department Commissioner Mickey Roache launched the Community Disorders Unit (CDU) to change that. It was the nation’s first “bias unit,” dedicated to combating civil rights abuses that were widely regarded as not worthy of prosecution. And for more than a decade, the CDU was a national model for how to take hate crimes seriously. The unit not only made significant arrests, it also changed the way data was gathered to show that racially motivated crimes were a persistent problem in American cities. Over time, once it became apparent that Boston’s police were serious about arresting whites for assaulting minorities—even if the attackers were minors— the number of racially motivated crimes in Boston began to decline.

It wasn’t long, though, before Southie got tired of seeing its white sons getting locked up for beating up Black and Asian kids, and residents began lobbying the police and local politicians to tame the CDU. Eventually, that’s exactly what happened. Beginning in 1994, BPD swapped out CDU’s longtime leader for a commander who was “sympathetic to complaints from Southie leaders about the squad,” as the Boston Globe’s Judy Rakowsky reported. More than half of CDU’s staff—including “some of the most aggressive detectives and supervisors”—were transferred out. While hate-crime complaints skyrocketed, enforcement plummeted. According to two police commanders interviewed by Rakowsky, by 2000, the CDU had “been effectively dismantled.”

Rakowsky’s story chronicled the nail in the coffin for the CDU, an act described as “symbolically telling”: the appointment of Sergeant Detective Duggan as assistant commander. The BPD had waited more than two decades, but it eventually installed Lynch’s killer as the day-to-day leader of the unit charged with combating civil rights abuses against Boston’s Black community. Rakowsky noted that during Duggan’s tenure, “no felony civil rights complaints have been brought by any detective under his supervision.” (Attempts to reach Duggan for comment were unsuccessful.) William Johnson, a former CDU commander who was appalled by the changes, said the BPD was “sending a message” with Duggan’s appointment. I invite you to share this story and tell us what you think that message was.

Lynch with his great-aunt, Julia Mack. / Photo courtesy of Joe Nipper

Back in 2015, as I was digging through the court records for the civil case Lynch’s family filed against Duggan, an archivist told me she’d found something unusual in the court file and handed me an old folder. At the bottom was the infamous clipboard: the one Duggan claimed was wrapped in a towel. Holding it in my hands, Duggan’s story became even more implausible—it was impossible Lynch could have swung something this size without the other eyewitnesses detecting it.

Those court files also contained Lynch’s medical records, and they revealed more about his mental state than was reported at the time. Though news reports sometimes referred to Lynch as someone with “a history of mental illness,” and even Adlow’s inquest finding referred to Lynch being incapacitated by a mental condition, Lynch had actually been diagnosed as schizophrenic during a stay at Bridgewater State Hospital the year before his death, and doctors at Boston City Hospital were aware of this on the day he was killed. To me, this made his shooting all the crueler and more tragic—it appears likely he suffered from an undiagnosed mental illness for much of his time in Boston.

For a while in the late ’60s, Lynch moved in with Dwellingham and his wife. When they weren’t performing, both men worked odd jobs to pay the rent, but they didn’t always earn enough to make ends meet. One day, when they were both working for an elevator repair company in Dorchester, Lynch offered to pawn his record player. “He said, ‘We don’t need to listen to no music.’ He took it to the pawn shop and pawned it so me and my family could eat,” Dwellingham says. “We were really brothers.”

In January 1969, Lynch was arrested for check forgery. Given what happened next, it seems likely that his as-yet-undiagnosed mental illness played a central role. Around that time, Dwellingham remembers that Lynch was “off.” They thought maybe it was drugs, though Lynch’s medical records show no signs of drug use, and the one time he was asked, he said the only drug he consumed was marijuana.

A month after his arrest, while in jail awaiting trial, Lynch was carried into Boston City Hospital, cuffed at the ankles and wrists, in a catatonic state: “motionless, unresponsive, and mute.” He hadn’t eaten in four days and wasn’t threatening anyone, but the police Maced him anyway. Doctors were unsure of what was wrong with him. They thought he might have lockjaw or tetanus, and diagnosed him with schizophrenia. (His medical records also suggest that he could have been suffering from an accidental overdose of Stelazine, an antipsychotic drug.) He spent the next two months under observation at Bridgewater State Hospital. In April, they found him coherent and healthy enough to send back to jail.

Dwellingham doesn’t remember any of that, but he does remember hiring an attorney who, he says, got Lynch out of trouble. By the dawn of 1970, Lynch was on the brink of stardom: They’d recorded “Young Girl,” the record was released, and both Dwellingham and Skippy White were convinced they had a hit. And yet while Lynch continued to perform with Dwellingham’s band, he was clearly troubled. The night before he died, they had a gig at Paul’s Mall in the South End. On the way there, Lynch was in a dark mood: “That night, before I took him to Paul’s Mall, he said, ‘I’m not going to be here long,’” Dwellingham recalls. “I mean, I didn’t think he was going to die, but he had a premonition. The man told me he was going to be dead.”

After the show at Paul’s Mall, Dwellingham took Lynch back to the house of Julia Mack, Lynch’s great-aunt, who’d raised him since his parents’ divorce. Twice that night, Mack called the police asking them to take Lynch to the hospital for observation; twice the police refused to do so without a doctor’s order. According to Nipper, Lynch urinated on a bed, then went around the corner to another family member’s house, where he got into an altercation with his uncle, pushing him through a sliding glass door. It’s not clear whether Lynch’s shoulder was injured during that fight or by the police who took him away. Both Lynch and his uncle were transported to the hospital, but neither

was arrested.

What Lynch desperately needed at Boston City Hospital that morning was mental healthcare; instead, he got a bullet to the brain. The system that failed Lynch over and over finally brought his life to a tragic end.

Lynch’s plight also reminded me of a similar case in 2016, when Roxbury resident Hope Coleman called 911 for medical help with her 31-year-old mentally ill son, Terrence. According to a lawsuit she filed against the city, shortly after EMTs arrived, two police officers shot and killed Terrence Coleman. The officers claimed he had a kitchen knife; Hope Coleman says there was no knife. What’s indisputable is that Hope Coleman—like Julia Mack a half-century ago—called for help with a troubled loved one, and instead saw him killed by the people sworn to protect him.

At a rally after Lynch’s funeral, the civil rights activist Hubie Jones said Duggan didn’t shoot just Lynch; he shot an entire community. For Dwellingham, the pain was simply too much. After Lynch’s death, the driving force behind so much of Boston’s nascent soul scene quit music. He didn’t play a note for three years. And when he resumed, he had to leave Boston to do it. He ended up in New York, recording hits with Weather Report and becoming an in-demand session drummer. The soul scene in Boston—seemingly poised for a breakthrough—never recovered.

For me, Lynch’s story encapsulates decades of Boston’s structural racism and the persistent systems that enforce white supremacy. But for Eli “Paperboy” Reed, the story is also more personal. After he recorded a version of “Young Girl,” Reed and Dwellingham struck up a friendship. One night in 2011, Dwellingham hopped onstage to play drums on the song that almost made him famous. It was a memory they both savor, but the thing that haunts Reed is how much talent was lost: “From the death of Franklin Lynch, all the way down the line to all of these African-American men who have lost their lives—there is an incalculable toll, an unknowable amount of potential that we’ve lost as a society.”