Ted Kennedy: A True Man of Boston

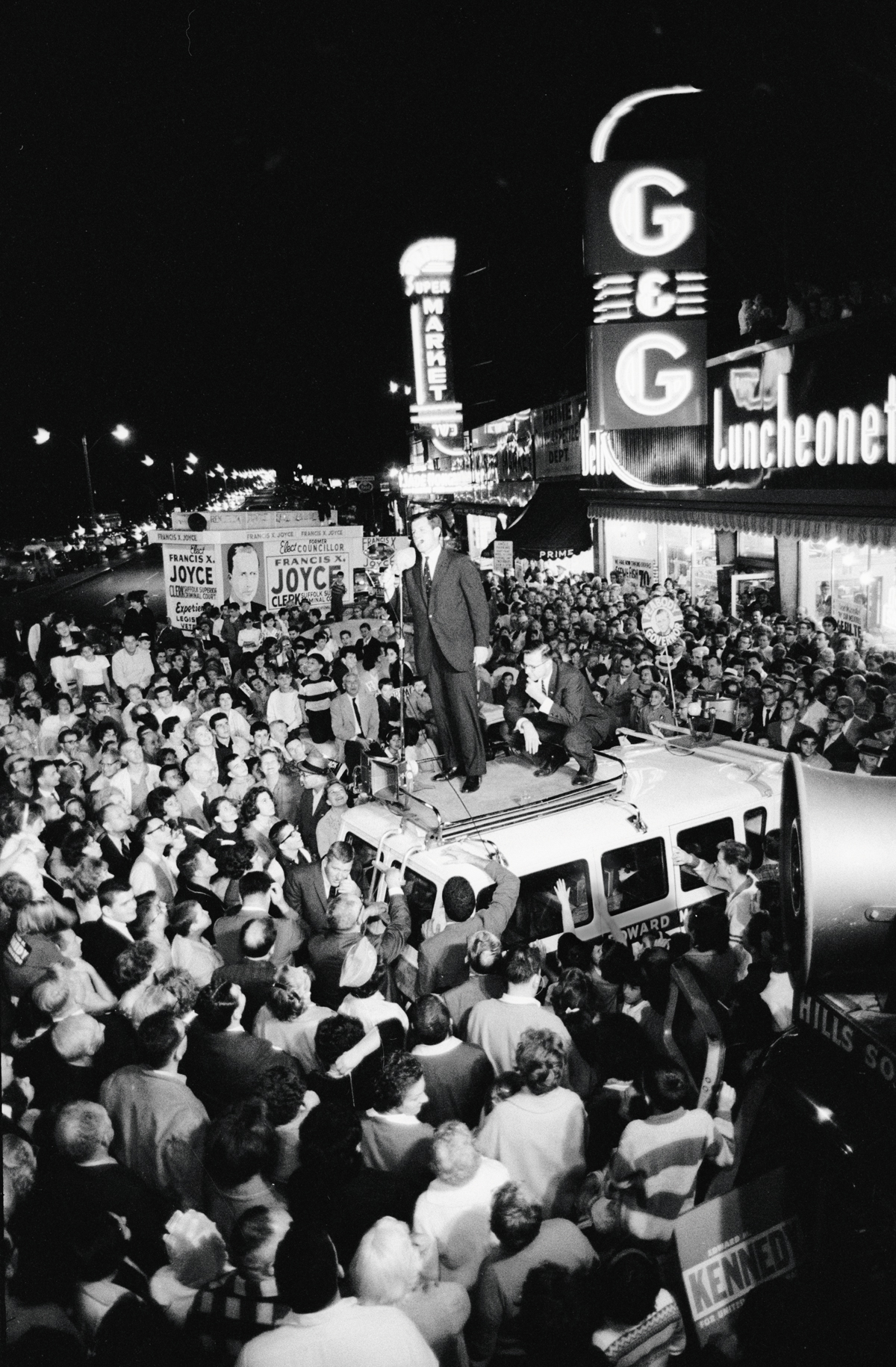

Photograph by Carl Mydans, Time & Life Pictures Collection

Ted Kennedy’s first major humiliation—the first of many (and many of those self-inflicted)—came at the hands of Eddie McCormack. The scene was Southie High in 1962. Young Ted was squaring off against the popular two-term attorney general in a debate for the Senate seat that John F. Kennedy had freed up when he took the White House. A tough Boston pol who shared more than a few chromosomes with JFK’s so-called Irish Mafia, McCormack planned to repay Teddy’s audacity with a ferocious public beating in an auditorium full of his rowdy, blue-collar supporters.

Up until that point, Ted Kennedy’s Boston bona fides were questionable, McCormack’s characterization of him as a parachutist not entirely unfair. Whatever his pedigree, Ted was raised mostly in Bronxville, New York; London; and Palm Beach. When JFK rose to power and Bobby declined to take the seat, Ted’s father, Joe Kennedy Sr., pushed his youngest boy to run, in spite of his brothers’ belief that he wasn’t remotely ready for the job. Teddy’s own inclination was to set out for the territories, maybe New Mexico, to plant his flag there. As Joe McGinnis wrote in his book The Last Brother, after Ted had campaigned for Jack in 13 western states, he found that “he felt far more at ease in the West than he ever had in Massachusetts, or Florida, or wherever he was supposed to consider home.” But his political prospects were brightest back in the Bay State; Teddy was savvy enough to realize that. So he stayed here, and ran against McCormack.

By then, the Kennedys were international players, increasingly removed from the hard-scrapping, cigar-chomping street politics of the Hub. The world was their constituency. To show that Teddy was indeed ready for the U.S. Senate, his father had him sent on a 16-nation tour of Africa with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Trips to Israel and Europe followed. When he arrived in Ireland—a country whose politics would become a passion—he was greeted with a haymaker courtesy of the Dublin Sunday Independent, accusing him of being a carpetbagger. “He’s coming because later this year he is due to be involved in a political fight back in Massachusetts,” the piece read. “He is playing the game political in what has now come to be known as the ‘Kennedy Method.’ You do not spend your time campaigning in your own little patch.” Even the Irish, many of whom kept framed photos of JFK next to their framed photos of the Pope (from whom Teddy received his First Communion), thought this kid was a punch line.

At the Southie debate, McCormack gleefully read the Independent story to the raucous crowd, leading off a blistering direct assault on his opponent, famously ending with the line, “If your name was simply Edward Moore instead of Edward Moore Kennedy, your candidacy would be a joke.” But however rattled Kennedy was by the savaging, McCormack hadn’t factored in how his performance would play on TV. In the auditorium, Kennedy was finished, exposed. But on TV, a cruel and sweaty anachronism from benighted pre-Camelot times had tortured a nice, handsome, respectable young man for no good reason, and the young man had stood up to it. Or at least hadn’t collapsed under it. Kennedy won the day. According to the Herald (setting a precedent for itself), Massachusetts had “voted its heart rather than its mind.”

Ted, smarting from the debate, quickly set to work as if his name were anything but Kennedy, like a true son of the soil. Thus was born the duality that has fascinated and appalled Kennedy watchers for more than four decades: Edward Kennedy versus Edward Moore. The former: a reckless scion of unchecked appetites, a disgraced shambles of a man. The latter: a tireless worker who took no votes or victories for granted. The story of Ted Kennedy is the story of the struggle between these two selves.

Ted’s unique knack for politics came more from the city of Boston than from the Kennedy aristocracy. Though he was essentially installed in office by his family and redeemed by TV in that pivotal debate, his skill, as it happened, was retail, the hustle—handshakes, back pats, and shoe leather. He lacked the brains of Jack and the messianic passions of Bobby, but he made up for it with the sort of tough Boston Irish ward politics that Ted’s father had disdained since some nobody blew his father out of the race for street commissioner in 1908. While the Kennedys were increasingly self-exiling from Boston (Jackie Kennedy later would be vocal in her dislike for the Hub), Ted was spending more time there.

After attending a whopping 10 different schools by the time he was 11, Ted finally settled into the Fessenden School in West Newton, and then did four years at Milton Academy before attending, and being expelled from, Harvard. While in the area, he spent many a Sunday getting to know his grandfather, John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald. In his biography of Ted, Adam Clymer set the scene:

“Before lunch, Teddy would go up to the suite the 80-year-old former mayor and congressman kept in the Bellevue Hotel near the State House. Newspaper clippings would be pouring out of his pockets, and Honey Fitz would be on the phone, offering condolences on deaths and hopes for quick recoveries to the sick. At lunch in the dining room, the former mayor was still a celebrity, and people would come up to talk about how business was in the North End, about discrimination against the Italians or the Irish…. After lunch, his grampa always took him through the kitchen to shake hands with the cooks, and then they would walk around Boston, seeing the place on the Common where British soldiers drilled, and the church where William Lloyd Garrison had preached against slavery, and they would look at the decaying port, now far behind New York’s in importance. He was learning about real problems from someone who was not preaching.”

There were shades of his grandfather in the legendary legislator Ted Kennedy turned out to be. He built a 24/7 constituent services operation that was the wonder of the Senate. His wheelhouse was everything from foreign wars to Mrs. McGinty’s husband’s funeral in Foxboro. It was an approach best summed up by Marty Nolan, longtime editorial-page editor for the Globe, in the pages of this magazine in 2004. “What he had then and still has is diligence and determination, political qualities that surpass charisma and IQ,” Nolan said. “He has all the tact and toughness of the youngest runt in a large Irish litter.”

For his entire life Kennedy remained profoundly interested in Boston history, the continuity of things, often doing for others what Honey Fitz had done for him. He was fond of jokingly denouncing staffers who couldn’t recite the entirety of “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere,” as he could, and did, often, as part of his rolling, decades-long meditation on Boston. When NBC’s Katie Couric asked him in 2004, “If you had to describe Boston in just a few sentences, how would you do that?” he said simply, “It’s the best of the past and the best of the future.”

Nowadays, it’s impossible to show some newcomer around the city without mentioning Ted Kennedy. In fact, it’s almost impossible to imagine what Boston would look like without his efforts. The harbor would still be a sump, without his furious lobbying over the span of two presidencies—H. W. Bush and Clinton—to help win hundreds of millions of federal dollars to undertake and complete the cleanup. The Harbor Islands would still be grim little mounds, had Kennedy not pushed for them to be designated national parklands in 1996. Now a marquee exhibit at the Boston Public Library, John Adams’s personal library would have stayed in storage, while both the Chelsea Street Bridge and the Bunker Hill Monument would have been in a sorry state, had he not secured millions for these local projects. The ports would have been dead, too: Harkening back to those long-ago Sundays, Kennedy won $6.75 million in federal money in 2002 to deepen the harbor’s channels to accommodate bigger cargo ships and reinvigorate the city’s ports.

In the late ’60s, backed by outraged neighborhood coalitions, Kennedy helped convince Governor Frank Sargent to call off what would have been an astonishingly destructive highway project, the Inner Belt, a serpentine monstrosity set to cut the city into pieces. Even more radically, he argued that the state be given the authority to build the highway underground, using its own money on top of the federal Inner Belt money. Nevertheless, when the time came to undertake that project, Kennedy was matched only by House Speaker and tunnel namesake Tip O’Neill in his dogged pursuit of federal dollars to minimize the amount the state would be on the hook for. When Ronald Reagan vetoed the project in 1987, Kennedy led the charge to override him, and then fought equally hard in the decade and a half afterward—frequently against Senator John McCain, who delighted in trying to shut off the spigot—to keep the billions of federal money rolling in as the project bloated.

More recently, Kennedy was instrumental in the healthcare reform effort in Massachusetts, bringing in $380 million in federal money to launch the program. This year alone he led the efforts to secure $666 million for Massachusetts schools and $4.2 million for local biotech research, among other achievements. All this came on top of his usual grinding devotion to constituent services and decades-long advocacy for hiking the minimum wage, improving education, supporting small businesses—a list of accomplishments so varied in size and scope that a full accounting has yet to be made. He’s now consigned to history. Suffice it to say, this would be a very different place, had Kennedy not bested McCormack so long ago.