Pocket Aces

Photograph by Sadie Dayton

Out here on the fraying fringes of Fort Myers,where modern sprawl melts into native Florida, and city into country, past squat single-story houses, auto-body shops, and an old cement plant, there is an unassuming low-slung complex, the spring home of a very interesting baseball team. Inside the place, two men sit at the end of the pitchers’ row, locker-room chairs back-to-back: the most important players, it may surprise you to know, on a team of them.

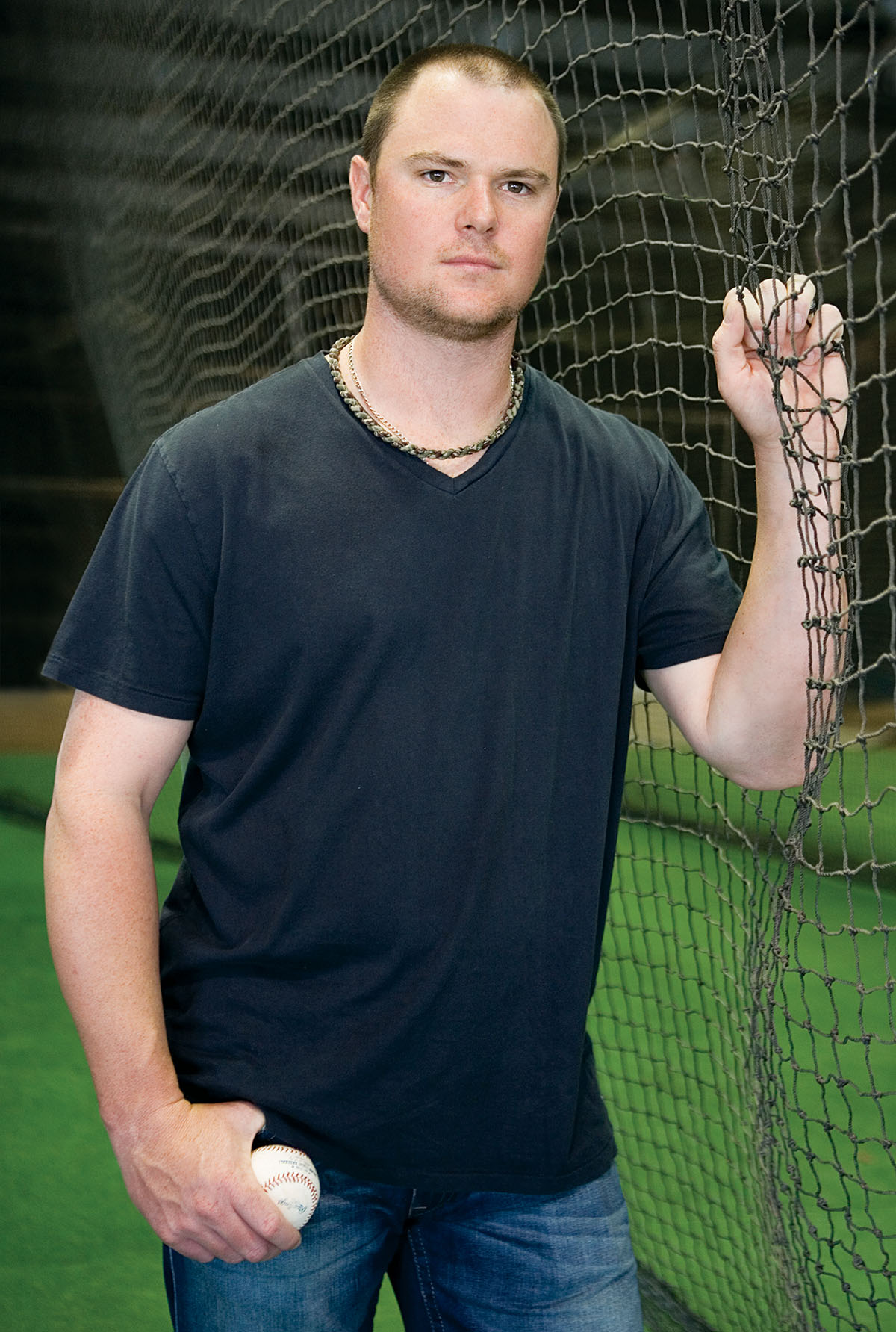

Clay Buchholz is the one with the scrawny Gumby physique, the wide-eyed, innocent smile and the long brown locks curling at the nape of his neck, strumming quiet chords on his Martin D-16, pausing only to spit the juice from his Copenhagen into an empty water bottle that rests on a nearby stool. Jon Lester is the bigger one, solidly built, wearing camouflage shorts, a camouflage-print necklace, and an impassive, squinting-gunslinger expression: the marks of the deerslayer.

There is little in the way of giddiness with these two despite the locker-room banter that swirls around them — the frivolity of late-February professional baseball players before spring-training games have begun. Shortstop Marco Scutaro holds up a pair of lime-green panties with a butt reading “Friday.” Closer Jonathan Papelbon lobs a pair of cleats tied by their shoestrings over a fluorescent light bank, where they catch and dangle like oversize baby shoes. Second baseman Dustin Pedroia swings a bat the way Braveheart’s Mel Gibson wields a club.

Lester and Buchholz are oblivious to the squall around them, though. They have larger concerns. On a team that is suddenly, preposterously, almost laughably good, they must be the best of all.

The Red Sox last year opened to high expectations, but their season devolved over the summer into something approaching bitterness, as the disabled list claimed ever more stars, and stud pitchers Josh Beckett and John Lackey underwhelmed. The season ended with the Sox finishing behind not only the mercenary Yankees but also the built-from-scratch Tampa Bay Rays. No playoffs, in other words, for Red Sox fans who have come to see them as something they are owed. And the whole thing would have been even worse were it not for the pitching of Lester and Buchholz, who each had an ace-level year, winning 19 and 17 games, respectively. They were the lone bright spots in an otherwise dreary campaign.

So dreary and dark, in fact, that the Red Sox brass decided drastic measures were in order. Was there some chance that fans — three whole seasons removed from the last championship — were beginning to lose faith? Not after an off-season in which the Sox traded for one of the game’s best hitters, slugging first baseman Adrian Gonzalez, and signed one of the very best all-around players in baseball, outfielder Carl Crawford. The message from management was clear: We will win. And we will win now.

Other Sox teams have been this good; the ’03 and ’04 editions come to mind. But back then, you didn’t have everyone from Newton to New Hampshire considering a World Series trophy his birthright. This year, though, with Pedroia and Kevin Youkilis and Jacoby Ellsbury healthy, and Big Papi hitting well, and Crawford stealing bases, and Gonzalez driving him and everybody else home — anything less than a ring will result in unmitigated rage, if not open revolt.

Jon Lester’s job this year: lead the Sox to glory. / Photograph by Sadie Dayton.

For all this team’s hitting talent, though, and for all the media’s focus on it, it is the Sox’s pitching that will define their success.

Beckett is good but nobody is expecting much, given his injuries and recent poor performance. Lackey may well be past his prime. And Daisuke Matsuzaka is always a question. The season rests, then, on the performance of Lester and Buchholz. Which may have something to do with their serious looks here in the locker room: The expectations have never been higher, the pressure never greater. The fans may not know it yet, but this is Lester and Buchholz’s club. Not that they’d ever admit as much. Ask Lester and all he’ll say is, “Our team has a lot to prove.”

Of course, given what these two have faced in the past — pressures more intense than the pursuit of a pennant — there may be few players on the team better equipped to handle what the most-hyped season ever will bring.

Jon Lester was always a pitcher in a rush. The Sox’s first pick in 2002, Lester signed for a cool million straight out of his Tacoma, Washington, high school. He then spent four years cruising through the system, meeting all the outsize expectations and reaching the top in 2006.

He won his first five decisions with the Red Sox. But as the hype grew, he began to unravel, the ERA soaring above 7 in his last seven starts. He had grown up watching the Seattle Mariners in a flanneled town where sports hovered somewhere between pleasant diversion and cultural afterthought. And Lester himself had never known athletic adversity. But now the pressure to succeed in baseball’s cathedral was squeezing the confidence right out of the kid. The game had become a job.

Lester demonstrates his form. / Photograph by Sadie Dayton.

Worse: The high-priced stud rookie on a veteran staff — Curt Schilling and Tim Wakefield were 39, Mike Timlin was 40 — felt alone. “It wasn’t fun,” he says. “It was too much, well, trying to fit in. We were a very veteran team. I didn’t really have a place. I didn’t fit in with a group.” He worried constantly: “Do my teammates like me? Do my teammates respect me?”

Then, of course, came the news. That August, Lester was involved in a minor traffic accident on his way to Fenway. The back pain lingered, and then grew worse. A trip to his doctor brought the shocking diagnosis: non-Hodgkins anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Cancer. Raised with a sense of stoicism by a mother who maintains the big trucks for Pierce County, Washington, and a father who’s a sheriff, Lester greeted the diagnosis without self-pity. His first thought was, Okay: What do we need to do to get rid of this thing?

Early treatments were successful, and by spring of 2007, Lester felt ready to pitch at Fenway. The Sox, though, wanted to send him down to rehab. What is there to rehab? Nothing’s hurt. Nothing’s wrong. But down he went, to Single-A Greenville. And it was there that he began to bemoan his plight, that he felt cruelly treated by fate, that he pitied himself.

And then he got himself together.

“One night I’m icing my shoulder,” Lester recalls. “And about four other guys and I just sat and talked about baseball till, like, 2 in the morning. They’re asking me questions, they’re 18 or 19, and they’re looking up to me the way I’m looking up to Josh or Schill. Just sitting in the clubhouse and talking to other guys, talking about baseball.” Their passion put a lot in perspective. “Really helped me get back and appreciate exactly what I do,” he says. Baseball, in other words, went back to being a game.

Lester’s numbers in Greenville: three starts, an ERA of 2.08. “He was having fun,” says Gabe Kapler, his manager during the quick stint there.

From Greenville, Lester kept having fun, coasting through a rehab assignment in Portland, pausing in Pawtucket, and receiving the call from Fenway in July 2007. On October 28, he won the deciding game of the World Series against the Rockies. Now that was fun.

By the time the 2008 season began, Jon Lester had reached a turning point. His trip back through the minors had taught him to enjoy the game and also not to mope after every loss, or celebrate after every win — including a no-hitter, which came in May of that year against the Royals. His combined 3.31 ERA for ’08 and ’09 earned him a long-term deal, signed in 2009: five years, $30 million. And while many players tend to slack off at the start of a big-money contract, in 2010 Lester climbed as high as he ever had: 19 victories. He’d become the team’s ace.

What has he learned along the way? Don’t lose yourself in the moment. Average out the numbers from your past three healthy years, and that’s more or less where you’ll be at the end of each year, slumps and streaks notwithstanding.

This new perspective has altered how he’s dealt with his illness, too. Nearing five years without cancer, he now knows that he’s an inspiration to other patients — a role that he desperately avoided at the start.

“I don’t want to be Jon Lester, cancer survivor,” he said two years ago. “I want to be Jon Lester, pitcher.”

And today?

“Well, tough shit,” he says now. “I’m going to be a cancer survivor. It doesn’t matter what I think. It took me a couple of years to mature and understand, to figure out that people need to see me that way.”

As is so often the case with young men who stumble, the misstep was of Clay Buchholz’s own doing. He was an 18-year-old freshman at McNeese State in Louisiana, pitching and playing shortstop. One night in 2003 he and a buddy drove back to his hometown of Lumberton, Texas, dropped through the ceiling of Clay’s old middle school, and, like a couple of Mission: Impossible wannabes, ripped off 29 laptops.

He was short on cash at the time, and the laptops were “just a way to make money,” Buchholz says now (pictured above right), with a trace of an embarrassed smile. “That’s all it was for me.” But this was also a moral felony; it brought shame to his parents, specifically his father, who had to given up on semipro baseball to marry Clay’s mom.

At the time of the theft, Buchholz had hardly expected baseball to provide a career. McNeese State wasn’t exactly a breeding ground for the Major Leagues, and hard-throwing right-handers weren’t a rare commodity. “I knew that it was a long shot — high school to college to pro ball,” Buchholz says. But because of the stunt, now there wasn’t baseball of any sort: McNeese State kicked him off the team.

Clay Bucholz stares down what lies ahead. / Photograph by Sadie Dayton.

“I paid for it, and I had a lot of people I had to apologize to,” Buchholz says of the laptop thefts. “It was not a good point in my life. I haven’t made a life-changing mistake since then.”

Buchholz was embarrassed, but he loved baseball too much to abandon it — he’d grown up idolizing no less a performer than Nolan Ryan — and the game, whatever the prospects, was his only marketable trade. So in 2004 he enrolled at Angelina College up in Lufkin, Texas, two hours north of Lumberton, determined to give baseball his full attention. The next spring, he took the mound for an intrasquad game under the watchful eye of coach Jeff Livin.

“I was umpiring,” Livin recalls, “because I like to stand behind the pitchers, because I want to be in their ear. But that day, there wasn’t anything to say. Clay faced six batters and struck out every one. No one got a bat on a single pitch. He threw nine or ten changeups.”

“Why throw that?” the coach asked.

“’Cause I felt like throwing it,” Buchholz replied. “Doesn’t matter what I throw. They’re not going to hit it.”

Buchholz went 12–1 at Angelina, his confidence expanding as his ERA shrank; by the end of the year it was a stunning 1.05. It was 2005, and Buchholz had made himself a genuine prospect at an especially fortuitous time for the Red Sox.

The minor-league system Red Sox general manager Theo Epstein inherited in 2002 was slow-footed and prospect-free — a shambles. At his first organizational meetings, he’d spoken of “building the machine.” So his decision three years later to select Buchholz in the first round reflected the young GM’s determination to gather the best available talent, even if a player’s past was a bit checkered.

For his part, Buchholz was delighted: “I was going to have a chance to play with guys I’d been watching on TV,” he says. He climbed easily through the Sox system. Within three years he was at Triple-A Pawtucket under the tutelage of manager Ron Johnson (now the Sox’s first-base coach). Johnson knew immediately that the kid wouldn’t spend a lot of time in Pawtucket. “He had that Bugs Bunny changeup, the fastball, the curve, and the slider. I thought, This could be the first guy I saw come through the system with four above-average pitches.”

Buchholz was called up to Fenway on August 17, 2007. In his second major-league start — about a month after Jon Lester had returned from his rehab trip through the minors — he no-hit the Orioles. And he did it emphatically. “He was so far in command of everything he did,” says Jason Varitek, who caught him that day. “It was just a special, magical moment.” The no-no was the first ever by a Boston rookie. By the end of the season, Buchholz was 3–1 — with an ERA of 1.59 — and that October, with Lester pitching the clinching game, the Sox won their second World Series in four years.

Thus did Buchholz waltz into Fort Myers the following February, figuring he would pick up in spring training where he’d left off. Instead, he fell on his face. He had the worst spring of any pitcher on staff. His no-hitter had been pitched free of pressure. But now, before the expectant eyes of Red Sox Nation, his confidence crumbled. After barely making the big-league roster, he lost nine of his eleven decisions. And with every hit surrendered, he found himself thinking, Here we go again.

In late August, Buchholz was sent back to the minors, all the way down to Double-A Portland. “It was sort of a shot to the face,” he says. Portland pitching coach Mike Cather stripped Buchholz’s approach to pitching back down to the basics. Slowly, the success began to return. Buchholz started the next year in the minors, and he dazzled. He dominated after a promotion to Pawtucket (one night taking a perfect game into the ninth inning), and earned his way back to Fenway in midseason, humbled and hungry. He won seven games and lost four over the rest of the season.

Bucholz on the mound. / Photograph by Sadie Dayton.

Coming off that strong second half in 2009, Buchholz entered the 2010 season determined to have a short memory. “There were games I’d screw up every now and then,” he says, “but it was the five days in between that were different than the previous years. I forgot about that game and went forth and just pitched the next one.” He finished a sensational 2010 season with 17 wins and a 2.33 ERA, second best in the American League.

That even-keel temperament suits Buchholz — one loss is just one loss, which means that one win is just that, too. Win or lose, though, Buchholz is playing for something more than the uniform. He says the success of last season, and what he’ll face this year, is really a way to honor his father, the man he’d let down and shamed with his teenage transgressions. The man who’d always wanted him to be the ball player he could not be.“I’m living his life for him, is what I try to do these days,” says the son, a smile lighting up his face.

The two men will need their newfound maturity. The expectation is for each to win 20 games this year. Both know it. And Lester asks for something in return: patience from a media scrum that is so often, well, immature in its judgment of the Sox, delivering pitch-by-pitch tweets and freak-outs after losses in April.

To Lester, a kid who grew up in the shadow of Mount Rainier, fishing in the local lake, the discordant immediacy of the Boston press puts undue pressure on the team, something he believes has contributed to its spasmodic performances over the past few years. “The thing is,” he says, “it’s hard not to come into the clubhouse and get caught up in that urgency [the Boston media] brings. That makes it hard on us. I know it’s their job. It’s what they have to do…but, We’re screwed! and all this stuff? When we’re still in April and they’re talking about us not making the playoffs?

“We’re only human. I know we get paid a hell of a lot too much money to play this game. But it’s not like we have a bunch of assholes on this team who don’t care. Everyone in that locker room cares. Everyone in that locker room last year cared. For you to give up on someone because they had a bad month or couple of weeks, it’s not right.

“I don’t think it’s fair to give up on guys,” he continues. So, who had the press given up on? Papi? Captain Varitek? Himself? All of them?

He declines to say. But there is perhaps something else in Lester’s declaration. The world is expected of his team this year. And it may be that it’s his team he’s actually addressing: Stay in the moment. Trust in each other. Believe in the promise of our talent.

In Fort Myers, it’s time to take the field. Outside the locker room, a few hundred rabid fans crowd against the white plastic fences as the men of spring jog from the locker room, beneath a giant, sheltering oak, out onto the distant fields.

Dustin Pedroia is first out of the building, and he receives rock-star yells.

Then Jonathan Papelbon is screamed after, and then Beckett, and then the new guy, Crawford. Youk gets a thunderous chorus, and the cheer for Big Papi swells high into the Florida sky.

Somewhere in between, though, the two pitchers jog out. They are afforded a polite welcome — nothing special. Their silent but vital voyages have made no headlines, no SportsCenter Top Tens. Neither of them cares. Because come November, if they do their jobs right, the cameras will know where to focus.