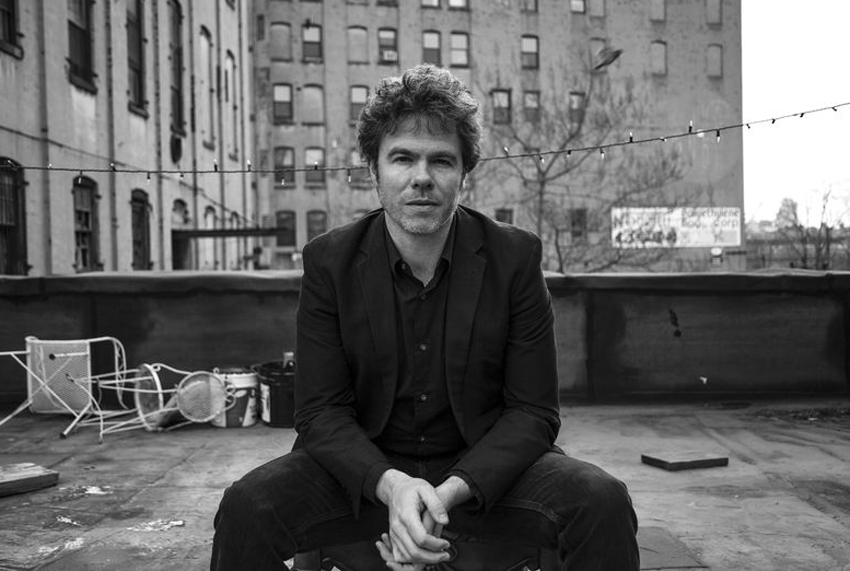

Q&A: Josh Ritter, the New Face of Folk

Josh Ritter and the Royal City Band perform at the House of Blues on Friday. (Photo courtesy of Laura Wilson)

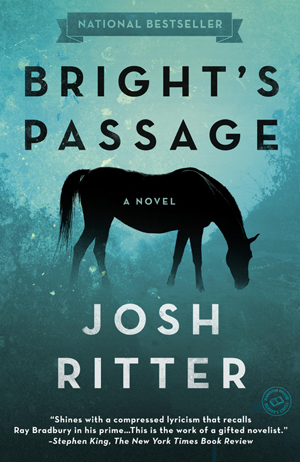

When Josh Ritter released his self-produced second album, Golden Age of Radio, for less than a thousand dollars, nobody expected the Moscow, Idaho, native to become the next Neil Young or Nick Drake, especially not Josh Ritter himself. But since that auspicious debut, Ritter has been named one of the 100 Greatest Living Singer/Songwriters by Paste magazine and his last three albums have all been in the Billboard Top 200. In 2010, Ritter tested a new genre and released the literary World War I novel, Bright’s Passage. which was heralded by NPR, The Los Angeles Times, and iconic authors like Dennis Lehane and Neil Gaiman.

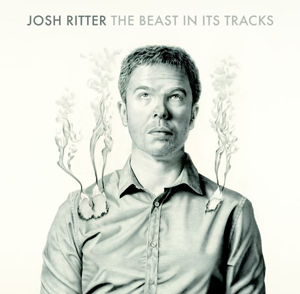

His newest album, The Beast in Its Tracks, is a stripped-down, melancholy response to his 2011 divorce from musician Dawn Landes. It’s been compared to Beck’s Sea Change and Dylan’s autobiographical masterpiece, Blood on the Tracks. In advance of his Friday concert at the House of Blues, Ritter talked about his humble beginnings in Somerville, the joys of rediscovering Fleetwood Mac, and the importance of always ending on a high note.

I’ve now seen you in concert a number of times and I have to say, you might be the happiest performer I’ve ever seen. Is playing live a big release for you?

Oh, it’s amazing! I grew up, like many performers do, as a very shy person. I’m lucky that for some reason, on stage, that goes away. It’s a weight that gets lifted. The stage is a place where I feel like I can do anything, like a weird going to sleep feeling. It doesn’t matter if the song is happy or sad. I’ve had some of my happiest moments writing the saddest songs.

I’ve read that your musical aspirations didn’t spring up until later on in your life. What were some of the catalysts that set you on this path?

I grew up playing violin and hating every single goddamn minute of it. But then, at 17, I discovered the guitar through Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan. This amazing thing happened where it let me be who I really was.

Was there any Dylan album in particular?

It was Nashville Skyline, that much-maligned country record. It had him and Johnny Cash singing “Girl From the North Country” on it. I knew Johnny Cash because in Idaho everybody does. But with Dylan, I’d only ever heard his name. He didn’t feel like an uncle like Johnny Cash did. So when I discovered Dylan, that was something really special.

Cover courtesy of Random House

I understand that you lived in Somerville for a while after graduating from college. How long were you there and when in your musical career were you at that point?

I was there from 2001 to 2005. I lived on Albion Street and in Arlington. I lived all over the place actually. I originally lived in Providence, but I was always coming to Boston to play the open-mics. Of course, [Club] Passim was the most famous place I played. It was a place that even I knew and had heard about. I also played the Kendall Café, All Asia, Kirkland Café, and underneath the [Union] Oyster House.

Will writing fiction ever be a full-time occupation or are you content to focus on that part of your life between tours and recording?

I think I’d like to keep doing it that way. I feel that if you have two fields you can grow one and the other one can lie fallow. I increasingly see in songwriting that [time away] is so important. You have to let things lie fallow so you actually have something to say.

Courtesy of Laura Wilson

You chronicled your struggles with So Runs the World Away in “Feeding the Monster” in Paste magazine. Did you find yourself in a similar predicament as you approached The Beast in Its Tracks?

In the case of So Runs the World Away, as it should have been, I didn’t know exactly what I was writing about. It was a work of exploration, in a good, healthy way. It was frustrating and scary at times because it felt like it might be the end of my career. But with The Beast in Its Tracks, it’s a record that’s very plainly about one specific thing. They were two very different experiences. I can’t imagine having had trouble writing [The Beast in Its Tracks]. I had to hold myself back a little bit.

At the beginning of the album, the tone is justifiably angry and cynical. But by the end, you seem to have accepted change and new love. Was it your intention to explore the pattern of emotions that emerge after something traumatic happens?

Initially, I thought I’d try to arrange things in the order of how I felt at the time. But as that happened, I just thought that I lost the dynamic of the record. I wanted to make the record listenable to people. By making certain choices I was making it into a concept record rather than about an album about a time in my life. I do believe that in all my records, I’ve never ended it on a “down” note. I just don’t believe in it. I want to leave a little fire to carry on into the next record.

Josh Ritter and the Royal City Band perform live at the House of Blues on Friday. Doors open at 7 p.m. Standing room tickets are $29, reserved seating $39.