Inside the Bunker at Boston Public Schools

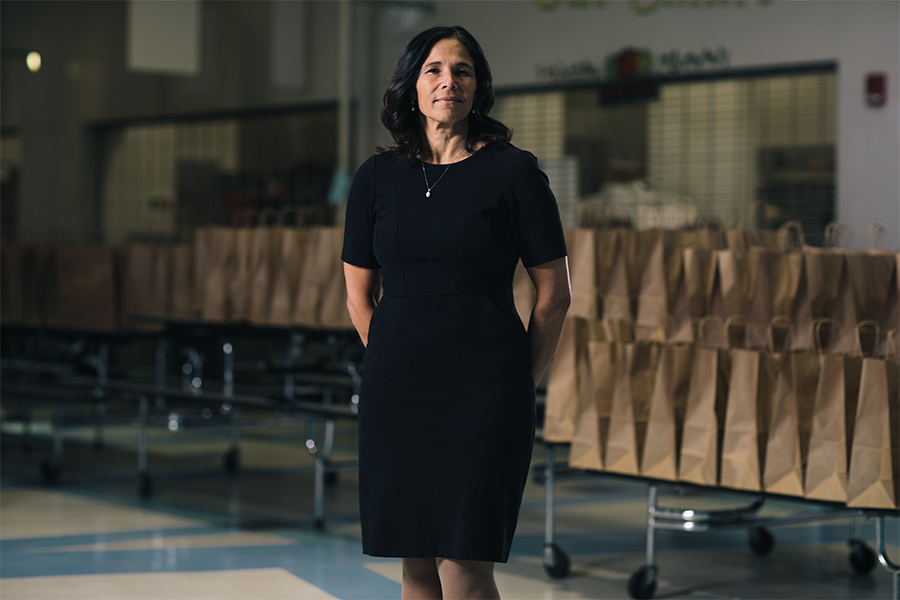

Brenda Cassellius, the head of BPS, has a vision for the future unlike any superintendent the city has ever encountered. And that’s a good thing—right?

Photo by Matt Kalinowski

It’s a gray and frigid morning in Dorchester when Brenda Cassellius bounds toward me on the front lawn of Joseph Lee K–8 School. She wears all black—pumps, dress, trench coat—and seems a little distracted. “Mask up, Superintendent,” an aide says, and she pulls her facemask over her nose.

Even though it is a Wednesday morning, Lee K–8, a sprawling red-brick building standing behind us, is mostly empty, staffed by a skeleton crew and completely devoid of children. It has been this way since March, when Cassellius and Mayor Marty Walsh decided to shut down every school in the district. Cassellius has barely stopped moving since.

“Sorry to keep you waiting,” she says. She had been sitting in her car for the past 45 minutes, she explains, on a conference call with other big-city superintendents brainstorming ways to reopen schools in the middle of a pandemic. That was after she already had two other meetings this morning.

“Do you mind if I run a tape recorder throughout the day?” I ask her.

“Day?” she responds, incredulous. She does not have a day to spend on me.

“Midday,” I say. “Run the recorder throughout the midday…”

But she’s already off.

Cassellius has come to Lee this morning to check on the work being done inside the cafeteria—a space as wide and tall as a gymnasium—where a dozen or so chefs are busily prepping packaged meals and bags of groceries. In a couple of hours, Boston Public Schools families will begin lining up at the door of the school, which has been turned into a food-distribution site.

Cassellius chats with the head chef, who shows her a color-coded calendar of the month’s meals. “Sweet potato fries!” Cassellius says, pointing at the calendar. “Oh, I want to come in on Thursday.” She seems simultaneously energized and at ease at the school. If she appeared harried outside, coming off her meetings and calls, she is now something much closer to jubilant. Over the next 40 minutes, as we tour the facility, she amiably talks to a janitor, a secretary, two assistant principals, and a security guard—while also dancing, leaping between social-distancing markers on the floor, and, on the playground, jumping down a hopscotch court. Yes, she is still wearing pumps. Back in the cafeteria, before we leave, she nods with approval as an administrator explains the school’s grocery-distribution system.

“I need to come hang out here more often,” she says. “Everything’s smooth and working great.” Then, almost speaking to herself, she adds, “Because in my life, it’s not like that every day.”

To say that Cassellius’s daily life in Boston has not been smooth is something of an understatement. She has one of the highest-stakes jobs in Boston, and the “second-hardest job in the city after mayor,” one source told me. (Second-hardest job in the country after president, another said.) When she arrived here in the spring of 2019, she inherited a system plagued by underperforming schools, yawning achievement gaps between Black and white students, decrepit infrastructure, and a distrustful relationship with the community it must serve. And that was before the pandemic hit, turning the district and her job upside down.

From the start, Walsh’s administration had hoped that Cassellius would restore stability to Boston’s struggling school system. Her driving passion, equity, seemed to make her a perfect fit for a district where inequality in academic outcomes is glaring. Before she even started the job, when she was still a candidate for the position, she had already seemed to achieve the impossible: winning the support of the community, the school committee, the teachers’ union, and the mayor.

Yet even by the standards of a city that has had five superintendents in the past decade, Cassellius’s first year and a half on the job since arriving from Minnesota, where she served as the commissioner of the Department of Education, has been tumultuous. She has overseen defections and ousters among her senior executives, a revolt from school principals, and public excoriation from influential nonprofits and activists. There have even been rumblings that she may not last much longer in her position.

So what went wrong? Was it the pandemic, which stalled Cassellius’s agenda and turned her job into mission impossible? Was it the superintendent herself, who, her critics argue, is too focused on visionary (and starry-eyed) future transformations to tend to the urgent problems of the present? Or, as Cassellius’s remaining supporters contend, is the problem that Boston—a city of sharp-elbowed politics and deep skepticism of outsiders—has refused to give her a fighting chance?

Brenda Cassellius has been criticized for her job thus far as superintendent of Boston Public Schools, though her supporters say she deserves time and a chance to implement her vision. Photo by Matt Kalinowski

As we left Lee K-8, Cassellius’s aide invited me back to the BPS central office for an interview. I paused. “Do the windows open at the central office?” I asked. They did not. Sensing the COVID-induced hesitation in my voice, the superintendent, who spends a lot of time in the field and knows every school building in the district inside and out, quickly offered another option. “Let’s go to TechBoston,” she suggested. “The windows open there.” Before her aide could object, she was off.

Once we got settled in a classroom at the school, Cassellius told me about her life. Because of her background, she says, she has a lot in common with many BPS students. The daughter of a young single mother who later became a young single mother herself, Cassellius grew up on food stamps in the projects of Minneapolis and participated in a Head Start program. Half African-American and half white, some of her formative experiences included being the target of hatred from adults. “I was called everything from the N-word to mulatto,” she says. “It was the early ’70s and people weren’t too nice to biracial children.”

Cassellius started her career as a special-education paraprofessional and soon rocketed up the ranks. She quickly won jobs as a teacher, assistant principal, and then principal of a middle school, after Carol Johnson (who would later serve as BPS superintendent) hired Cassellius to work in the Memphis school district where she was superintendent. By then Cassellius had earned a reputation for being full of energy and big ideas. “She’s a quick problem solver,” says Bernadeia Johnson (no relation to Carol), a former superintendent of Minneapolis Public Schools. “She sees something and she does it.” Cassellius’s decisiveness and big ideas, however, sometimes ruffled the feathers of more “traditional” colleagues, Johnson says. “When you are really smart and your mind is moving a lot, sometimes you have to take the time to pause and hear from others.”

Carol Johnson saw both promise and room for growth in Cassellius. One day in 2004, Johnson walked into Cassellius’s office to offer her the biggest promotion of her life. I want you to run academics for Memphis middle schools, Johnson told Cassellius, assuring her she could handle the job overseeing 31 principals, many of them decades older than her. Then she added an admonition: “You need to grow in humility.”

Stung by the criticism despite the vote of confidence, Cassellius went home and cried. Then she reflected. “I was such a go-getter,” she told me, “and confident and, you know, dig in. That kind of knocked me down a peg.” She picked herself up by reading “every book I could find about the craft of leadership,” she said. “And I started to do things where it wasn’t just my idea, but everybody’s idea.”

Over the next 15 years, her career remained on a steady ascent. Back in Minneapolis, she served as an associate superintendent from 2007 to 2010, overseeing high school principals. Then, as a superintendent for the first time, she briefly led a two-school district. For the next eight years, she served as Minnesota’s commissioner of education.

When Cassellius arrived in Boston to vie for the BPS top job, she pitched herself as a deft political operator laser-focused on equity. That’s exactly what Boston needed, says Tanisha Sullivan, president of the Boston chapter of the NAACP. Cassellius had the “political acumen necessary to be successful in Boston” and also understood the “critical role of educational equity and the needs of Black and brown students, as well as low-income students and English-language learners.”

Cassellius, who was pursuing several jobs at the time, said she felt especially drawn to the Hub. “For some reason, I just felt like I was supposed to be here in Boston,” she told me. “I feel like I am put in places where I need to be for that reason. And now I know it’s for getting us through this pandemic.” Her confidence, and her self-belief, paid off. With the backing of the teachers’ union, community activists, and Mayor Walsh, she won the job in May 2019, with a 5–2 vote from the school committee.

Aware of the long history of distrust between BPS families and the district itself, Cassellius made a listening tour her first order of business. During the second half of 2019, she visited every school in the district and met privately with parents, religious leaders, activist groups, and politicians. The tour earned her a lot of goodwill. At the Horace Mann School for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, for instance, she wowed teachers and parents when she started communicating with children in American Sign Language. At the Joseph P. Tynan Elementary School in South Boston, she toured the hallways and classrooms with parents and their students, letting them know that she believed the school belonged to them. People felt heard. “I had never met with a school superintendent,” says Matthew Thompson, pastor of Jubilee Christian Church in Mattapan, the biggest Protestant church in New England. “She asked me what I would do if I was superintendent.” Meanwhile, she funneled what she had learned on her listening tour into a strategic vision plan that laid out a roadmap for BPS’s next five years.

Cassellius often describes her plans for reform as “bold,” which is also a good descriptor of Cassellius herself. After completing the proposal, she walked into the mayor’s office with her pitch: Add an additional $100 million to BPS’s budget. It worked. The school committee approved her plan and Walsh agreed to the budget increase. On January 8, 2020, in his State of the City speech, Walsh called out Cassellius by name, saying she was working hard to give “every single student access to high-quality schools.”

Cassellius says she felt she was flying high, on her way to achieving her vision for a better, fairer BPS. “We had all this wind under our wings,” she says. “The community was behind us, the mayor’s speech was inspiring, we had secured this new investment, and then, boom, here comes the plague.”

At the same time, not everyone agrees with this rendering—a soaring start to her superintendency derailed by a once-in-a-lifetime catastrophe. The trouble, according to interviews with 14 current and former BPS officials who have worked directly with Cassellius, and who spoke anonymously for fear of professional consequences, didn’t start with the pandemic. It began when the new superintendent came to town.

Cassellius speaking to the media with Mayor Marty Walsh, who says he is and has always been confident in the superintendent. Photo By Matt Stone/ MediaNews Group/Boston Herald

On an unseasonably warm day in October 2019, Brenda Cassellius took the floor during a meeting at the Bolling Building, BPS’s headquarters in Nubian Square. She was just four months into her job as superintendent and had a bold idea she wanted to share. Speaking to a room full of staffers and principals, she explained her vision for the next generation of Boston’s high schools. The staffers, all veterans of public school administration in Boston and beyond, listened closely.

The new schools, she said, would be built along—or on top of, it wasn’t exactly clear—the Emerald Necklace, the winding park running through central Boston. She envisioned that when students arrived in the morning, they would receive a “playlist” of programs available at each of the schools, according to BPS officials with knowledge of the plan. Then, throughout the day, the students would shuttle between buildings on a train.

The BPS officials listening to this concept were stunned. “It was a flight of fancy,” one former principal says. The Emerald Necklace—a narrow, marshy landscape designed by Frederick Law Olmsted—could not possibly be the site of a half-dozen or more high schools. Nor could the surrounding city blocks, which encompassed some of Boston’s most expensive and densely populated neighborhoods. What’s more, there was no train running along the park’s length. BPS was a troubled district; that was no secret. Big changes and bold visions were called for. “But plans and strategies have to be tethered to reality,” says one former BPS official, “and that just doesn’t include an imaginary train taking kids around a city to schools that don’t exist.”

In many ways, this was classic Cassellius, BPS insiders say. During her early tenure, staffers at the central office found the new superintendent to be more drawn to splashy proposals than to the grinding back-office work they believed was required to solve the district’s problems. She had a habit, seven current and former officials say, of tossing out big ideas that were often unrealistic and did not appear connected to any coherent plan. “What was frustrating,” one former official says, “was that they were often mutually contradictory.” They were also disruptive. Subordinates would scramble to respond to her proposals, pulling staff away from the business of running the school district. “She paralyzes the organization through her incoherence,” another former official says.

Her colleagues found her leadership erratic in other ways as well. According to five current and former BPS officials, she often appeared to make snap decisions, seemingly without contemplating their ramifications. Once, in August 2019, Cassellius returned to the Bolling Building in tears from a visit to the McKinley South End Academy, which was housed in a decrepit building. Dismayed by the prospect of sending kids to school there, she asked her staff to find a way to close it—along with another dilapidated school, the Jackson/Mann—and send the students elsewhere. In theory, this was a fine idea. The problem was the timeline: She wanted it done now, before the new school year began the following month. Cassellius’s staffers were stunned that she believed it was possible to shut down two school buildings in a matter of weeks, when that process normally took years.

Current and former BPS officials came to believe that the root causes of Cassellius’s scattershot ideas were her lack of attention to detail and short attention span. Previous superintendents had done deep dives into the details of how the district ran. “But with Brenda,” one former official says, “word came down that if your presentation was more than a few slides, you would lose her.”

In some cases, that lack of attention paid off. Under previous superintendents, BPS executives had used a complicated formula to calculate the annual budget increase they would request from the mayor. “Brenda ignored all of that,” a former official says. She walked into the mayor’s office, asked for $100 million, and got it. “There was a moment when I thought, Maybe she’s this madcap genius,” the former official says.

Despite Cassellius’s public victories, though, BPS officials were alarmed by the mounting evidence that she was an ineffective administrator. This didn’t come entirely as a surprise. When she was selected as a finalist in the spring, BPS staffers at Bolling, as well as executives at education nonprofits, had called their contacts in Minnesota to get the scoop on the promising candidate. What they heard was troubling: Cassellius lacked strong executive leadership and strategic planning skills. Further, just before applying for the superintendent role in Boston, she had been turned down for the same job in Minneapolis. Her hometown school board, which had watched her work closely for years, passed her over, citing the scarce progress on closing achievement gaps during her eight years as the top education official in the state. “Her leadership skills are very lacking,” a former Minnesota Department of Education official who worked with Cassellius told me. “She’s scattered, she struggles with talent management, and she doesn’t provide a clear vision.”

Those traits were on full display once she arrived in Boston. As she traveled the city on her listening tour, Cassellius issued a flurry of staffing directives that often went unannounced and unexplained. She implemented a hiring freeze, eliminated key central-office roles, and repeatedly reshuffled the organizational chart, according to three current and former BPS officials. By the fall, when students returned to school, BPS officials were having trouble keeping track of who reported to whom and what responsibilities belonged to each department. “It was chaos,” says a current BPS official. “Everyone was going every which way without direction, without leadership.”

Meanwhile, the senior leadership ranks cleared out as incumbents defected (Cassellius’s chief of staff “left in complete and utter dismay,” a current BPS official says) or were pushed to resign. BPS officials stress that the superintendent had every right to put her own team in place. But they found her methods strange. According to four current and former BPS officials, she has offered multiple BPS employees significant promotions seemingly on a whim, with little knowledge of their track records. The promotions left colleagues, and sometimes the promoted employees themselves, baffled. “She has said to me that she hires people based on familiarity and trust,” says Edith Bazile, a former president of the Black Educators’ Alliance of Massachusetts who has worked closely with Cassellius on a volunteer basis. She does not seek out people, Bazile says, “who are going to push her, interrogate her process, and ask provocative questions.”

Even more unnerving was the growing sense among BPS staffers that Cassellius herself realized she was in over her head. In meetings, she often broke down in tears and said she felt overwhelmed, according to three people who witnessed these episodes. “I don’t like to criticize people for crying because it’s often a form of sexism,” says a current BPS official. “But it’s more than that. It’s that she was falling apart.”

In October 2019, Cassellius reached for a lifeline, hiring Charlene Briner as her new chief of staff. Briner had been her right-hand woman in Minnesota, serving as chief of staff and then deputy commissioner throughout Cassellius’s eight years leading that state’s Department of Education. “Charlene has a way of coaching Brenda,” says the former Minnesota Department of Education official. “Without Charlene, I don’t think Brenda would have survived.”

In the months that followed, Briner helped prop Cassellius up, sometimes almost literally. Once, a BPS official saw Briner and Cassellius huddled in a hallway in the Bolling Building. The superintendent was about to go into a meeting and she was “falling apart,” the official says. Briner stood close to her and said, “‘Let’s breathe in. Let’s breathe out. You can do this. You have a vision,’” according to the official. “It was like out of a movie,” the official says, “like she was propping up the queen who you know is not up to the task.”

Briner said she did not recall this specific episode but that the comments sounded like something she would say to any colleague going through “a difficult moment.”

In an interview in a BPS classroom, Cassellius dismissed her critics as disgruntled employees. She said her Emerald Necklace concept wasn’t a plan but a prop or visioning tool. “It’s a very bold vision,” she said, “to get people to stretch their thinking.” Of her big ideas, she said, “The good ones stick and the bad ones fall away. That’s my style, and I think people are getting used to that now.” She said that ultimately it was not possible to close McKinley and Jackson/Mann before the 2019 school year began, but that if she could have done it, she would have. Cassellius added that there’s nothing wrong with showing vulnerability by crying. “As a leader,” she said, “it’s good for people to know that you’re human.”

Cassellius’s colleagues, and many of her sharpest critics, however, have never questioned her humanity. “Her heart is in the right place and I believe deeply she is a good person,” says a former BPS official. “But when you’re in charge of a school district for more than 50,000 students, being nice isn’t enough to prevent us from being honest that she’s not getting the job done.”

By winter of the 2019–2020 school year, concern over Cassellius’s leadership had extended beyond the central office and reached BPS’s principals—some of the district’s most important employees. A new wave of trouble began with another of Cassellius’s bold ideas, her so-called High School Redesign Plan. Unveiled in early 2020, it laid out an audacious vision for the future, proposing that seven large high schools across the city simultaneously expand Advanced Placement and pre-AP courses, create technical and vocational education tracks, offer dual enrollment with local colleges, implement International Baccalaureate programs, and expand to include the seventh and eighth grades.

The combination of all of these measures made principals’ heads spin. To some, the practical barriers to implementing the plan seemed nearly insurmountable. What’s more, in a district with chronically declining enrollment, it wasn’t even clear to them that there would be enough students to populate all of Cassellius’s new programs. It seemed, to some principals, like she was trying to fix the high schools with a magic wand.

It wasn’t long before the principals made their dismay painfully public. In July 2020, they wrote Cassellius a letter—which was leaked to the Boston Globe—excoriating her redesign proposal as a “top-down exercise in poor planning” that is “divorced from any authentic analysis of data, lacks major details that must be thought through prior to implementation, [and] ignores years of studies about BPS high schools and the complex issues they face.”

“It caught me off guard,” Cassellius admitted during the interview in a BPS classroom. Even with her facemask on, her expression made clear that the episode had been painful.

All of this landed in her lap precisely when the district was trying to figure out how to reopen schools in the fall. On July 22, less than a week after the principals’ letter was made public, Cassellius appeared, via Zoom, before the school committee to present a draft of BPS’s reopening plan. There wasn’t anything particularly unusual about the plan—it called for rotating cohorts of students to attend school two days a week while teachers used a combination of Web-based and in-person instruction. The problem, Cassellius’s critics alleged, was that it arrived too late and too light on details. “If we heard this plan two or three months ago, we may have said, Let’s all work toward this,” said Shah Family Foundation executive director Ross Wilson, whose organization works closely with BPS, on a podcast the next day. “But hearing it 49 days before the school year starts doesn’t give you much hope.”

The teachers’ union also criticized the plan, calling it “totally out of touch with reality.” In the midst of the pandemic, a teachers’ union taking a shot at a superintendent should be as shocking as an April snowstorm in Boston. But for Cassellius, it signaled that she was losing one of her first and most powerful allies. (Later, in December, the teachers’ union would pass a vote of no confidence in the superintendent.)

Publicly, at least, Cassellius still had the backing of the two allies she needed most: the school committee and City Hall. However, out of public view, their support was wavering. Through the early summer, officials had grown concerned that Cassellius and her new leadership team might not be up to the task of managing the pandemic response. They began considering an intervention. In mid-summer, City Hall and school committee officials called several current and former BPS staffers. According to sources with direct knowledge of this effort, as well as contemporaneous records, the officials were seeking candidates to step into a new role: czar for BPS operations and pandemic response. The move would have rendered Cassellius virtually a figurehead, still nominally in control of the district, but with many core responsibilities removed from her portfolio.

The plan, which was pursued without Cassellius’s knowledge, was never consummated. But it shows that her top allies’ confidence in her was rapidly eroding. When I asked Mayor Walsh about this effort, he said it would be false to characterize the role explored over the summer as “a checkmate to Brenda.” However, he said that as of December, Cassellius was seeking to hire a new operations director. This new official will be more senior than Cassellius’s chief operations officer, the mayor said, and will have a broad scope of operations duties, including “school facilities, transportation, and food.” Walsh added he is confident in Cassellius and always has been.

Even though the July intervention did not come to fruition, Walsh still took measures to bolster the central office. In the summer, McChrystal Group, a consultancy that has worked with the mayor at City Hall, began running Cassellius’s weekly coronavirus update calls with principals. Then, in late July, Walsh sent Patrick Brophy, the city’s chief of operations, to help with BPS’s reopening effort. The mayor and Cassellius say they arrived at the decision to have Brophy help BPS together. But BPS staffers and observers perceived Brophy’s work as an emergency rescue mission. Brophy might have seen it this way, too. According to a person who spoke with him multiple times in August, the COO said, in colorful language, that Cassellius’s team’s preparations were so far behind schedule that it would require drastic measures to open school buildings in time. (In an interview in December, Brophy said his work with BPS over the summer was less a “rescue mission” than an “all-hands-on-deck” situation.)

A bitter irony of 2020 is that even if you believe, as Cassellius’s critics do, that she mismanaged the coronavirus response, it is not clear how much it mattered. In districts that were well managed and in those that were not, the results have been largely the same: learning loss for students and hardship for parents and teachers. But even if the consequences of the pandemic are not Cassellius’s responsibility, the recovery from it will be. In 2021, school districts will face the daunting task of repairing the damage sustained during the pandemic—particularly for low-income children of color who have borne the brunt of the school shutdowns. For this Herculean challenge, leadership will matter.

In one light, Cassellius looks like the ideal person for that mission. After all, equity is her driving passion. Still, Cassellius’s critics and some of her former supporters fear she is ill equipped to tackle this next challenge. “She does view her job in terms of improving equity,” says Keri Rodrigues, a prominent Massachusetts education activist, “but wanting it and being able to make it happen are two different things.”

Edith Bazile, a vocal supporter of Cassellius during the superintendent selection process, has since concluded that Cassellius doesn’t have what it takes to lead the district as it emerges from the pandemic. She is too focused on big-picture plans, Bazile says, and “she does not have the leadership tools to put in place policies that are going to make those plans actually occur in reality.” “It creates a level of desperation,” Bazile adds, “because we can’t lose this generation.”

On the afternoon of November 13, I joined a Zoom call with Cassellius, her chief financial officer, her chief operations officer, and some of her favorite people in the district: her cabinet of student advisers. “Hi, Wellington. Hi, Rose,” she said brightly. “Hey Marcus, what you got going on these days?”

For the next hour, she listened warmly and keenly to the advice of her most important constituents—students. And she sincerely sought their counsel.

“Anything you think we should spend money on, you guys?” she asked. “We have $36 million outside of the normal cost.”

As the students offered suggestions—free menstrual products, cleaner bathrooms, improved ventilation—Cassellius had her executives take notes. As CFO Nate Kuder completed a preview of the public budget presentation he would give in February, Cassellius proposed an idea. “You know what would be kind of cool, Nate, is having a youth portion of the presentation.” Kuder said he loved the idea. “That’d be pretty powerful,” Cassellius said.

Throughout her tenure as superintendent, Cassellius has seemed happiest—and told her colleagues she’s happiest—when she is in schools and with children. Perhaps that is why she seemed so buoyant when I visited Lee K–8 with her and why she meets regularly with her student cabinet, and with BPS’s student advisory council. “She has a deep gift for connecting with children,” says a current BPS official who is critical of her leadership. “When [Cassellius’s predecessor] Laura Perille was in front of an audience of children, she seemed stiff,” the official says. “Brenda runs down the aisle giving high-fives and the kids eat it up. They love her.”

It is not hard to imagine how a person with this gift, as well as Cassellius’s taste for disruptive, visionary thinking, could be a good fit for superintendent of BPS, a district that’s long had a broken relationship with the community. Cassellius insists she will still be that leader, as long as the city will let her.

When I told Josh Collins, Cassellius’s former spokesman at the Minnesota Department of Education, about Cassellius’s troubles in Boston, he said some of the dynamics sounded familiar. In Minnesota, he explained, he and Cassellius shared a frustration that an entrenched bureaucracy stood in the way of bold change. “We talked about that challenge routinely,” he said. “How to capture people’s hearts and get them to come along rather than succumb to the tendency to keep doing things the same way.”

If Cassellius’s critics are wrong about her, then this is how: She has arrived in an institutionally conservative city that has a well-documented skepticism of outsiders. She has taken charge of a flailing school district and recognized the need for bold and uncomfortable changes. She is confronting an entrenched bureaucracy that wants to pursue incrementalism, rather than radical reform, and she is determined to shake the cobwebs free.

That is exactly how Briner sees it after working alongside Cassellius in Boston. “The swiftness of criticism,” she told me, “and the willingness to condemn, it’s something uniquely Boston. It’s been, what? Seven, or eight, or nine superintendents in a relatively short period of time? It does not seem that there is any appetite to give people room to prove themselves.”

If Cassellius shares that sentiment, she was too diplomatic, in most of our conversations, to say so. But she knows where she is. “I don’t want this to come off negative,” she told me in our first interview, “but I think there’s almost a sense of pride in that Bostonians say they’re hard on people, just like in Minnesota we have ‘Minnesota Nice.’”

Paul Reville, who served as secretary of education under Deval Patrick and is a supporter of Cassellius, says Cassellius needs to be given time. Building consensus, he notes, is “a long, agonizing process. She’s had an extraordinarily difficult maiden year as superintendent, and I think she’s performed remarkably well under the circumstances.” But, he adds, “There have been times when Brenda had such a bold vision that it’s overwhelming to people. They can’t see how to get it done, and she hasn’t shown them the steps along the way.”

In our conversations, Cassellius seemed to ask for two things: time and skepticism of her critics. Near the end of our final interview, during which I detailed her critics’ charges, Cassellius cut me off.

“Who is giving that criticism?” she asked me. “What are their intentions and motives? When you are disrupting the status quo with an anti-racist lens, as an African-American woman, you have to think about the motives of why people might be criticizing the ideas and the disruption that I’m making so that underserved children can be served better and to create opportunity and access.

“The criticism is premature,” she added.

As this story went to print, Cassellius was preparing for a virtual “retreat” with the school committee. She was looking to the future—a future beyond the pandemic—and was on the verge of unveiling her new vision, a plan she called Return, Recover, and Reimagine.“We’re going to be really reframing and pivoting,” she told me, “because our five-year strategic plan”—the one she announced a year ago, parts of which were later lambasted by the principals—“has gotten very little attention.”

The new plan, she said, would increase the budget, close achievement gaps, and turn BPS into “a real 21st-century school district.”

This time, she said, “we’re going bold.”