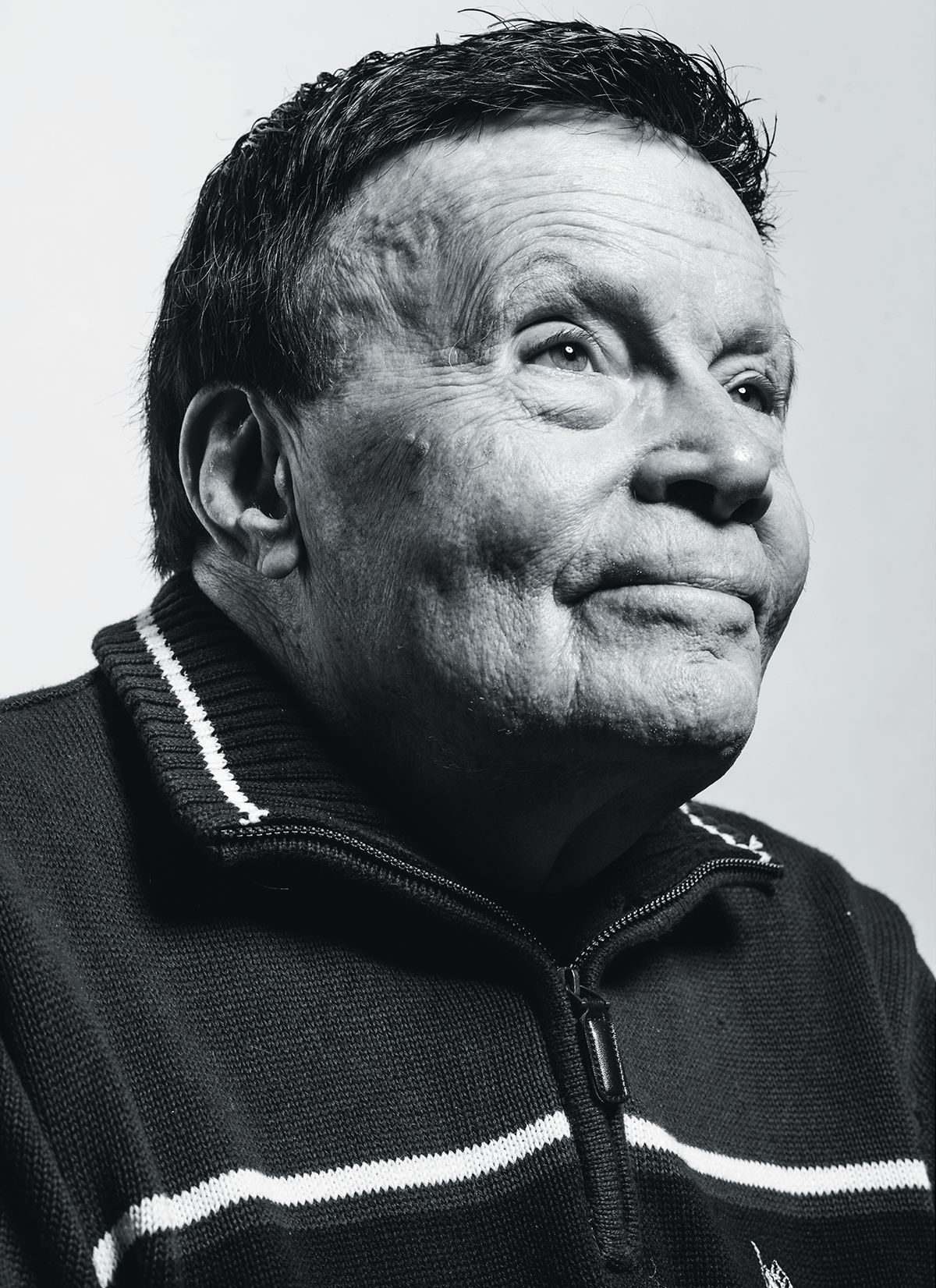

Memoir: Upton Bell’s Road Back

Photograph by Toan Trinh

It was a cold and windy day as I walked to Harvard Square to pick up my rental car. It was January 23, 2015. What did I expect, Red Sox spring-training weather? I was going to NECN to do an interview with Jim Braude on his show Broadside. The subject was Tom Brady and the beginning of a disease that has finally settled, known as Deflategate. It was the week before the Super Bowl between the Patriots and Seattle Seahawks. I had also brought my 1970 Super Bowl ring (I won it as the director of player personnel for the Baltimore Colts) to show the audience. When the show finished, I got in my car and headed home. While driving the short trip in 6 o’clock traffic, I thought about how the original plan—my longtime girlfriend, JoAnne O’Neill, was to drive me to the show and have dinner with me afterward—would have been much better, considering the traffic and the weather. But she had come down with the flu and couldn’t do it. Little did I know the role fate would play.

As I approached Route 2 off of 128, the traffic was fairly light, and I noticed the Channel 5 helicopter overhead. Whether my mind wandered or I hit a patch of ice or had a mini stroke, something happened that I still can’t explain. My car veered off Route 2, up an embankment, through a guardrail, flipped over, and landed upside down on top of another car. In the brief time my car was airborne, I had the feelings of flying and invincibility. I could hear the air. I was totally at ease and felt happier than ever before. Was it part of a near-death experience?

Quickly, this dissolved into severe pain. My first thought was, “Am I dying?” Luckily, somebody at the scene called 911. A police officer later told a TV crew that if my car had landed 5 or 6 feet in any other direction, both I and the woman who was driving the other car would have been crushed to death. I was much relieved when I found out she had suffered only minor injuries.

When the EMTs arrived, one of them carefully placed a collar around my neck, which was broken in two places. I remember nothing about the ride to Mass General, but after X-rays there, I learned I had a total of 39 fractures, including in my spine, sternum, ribs, and coccyx. I also had a concussion. I was very lucky I wasn’t paralyzed, beheaded, or dead.

After 37 years in pro football (including stints as general manager of the Patriots and owner of the Charlotte Hornets in the World Football League), then 39 years in radio and television in New England, here I was in the most frightening moment of my life. In just a few seconds, I went from Upton Bell the media personality to Upton Bell in the intensive care unit.

I’ve always tried to live by the words of the playwright Edward Albee: “If you have no wounds, how can you know you’re alive?” In the coming months, that outlook would be sorely tested. For the first time in my life, I was helpless. I got to see how inadequate our healthcare system is, particularly Medicare and its many ways of saying “no.” I also faced the great danger of becoming addicted to opiates.

At the same time, I learned the powerful role an advocate can play, and was lucky to have two in JoAnne and my son, Christopher Bell.

I hope you’ll take this trip with me. It’s not always pretty, but it may help. The questions we all have to ask ourselves are, Do I want to live? and How valuable is life?

During my first three days in the hospital, besides vivid dreams brought on by morphine and other drugs, I was aware of very little except visits from JoAnne, Christopher, the novelist William Martin and his wife, Chris, and my cousin George Bell. One of the more surreal things that happened was a visit from a camera crew following people who had been brought into the ER. I’m told I was euphoric, outgoing, informative—all the things I would be if I were on Charlie Rose. The people shooting the documentary seemed to like the interview so much, they said they’d be back. I never saw them again. I should be used to this given that, in my profession, one’s career can end very quickly.

Snow began to fall heavily in what would be one of our worst winters, though because of my injuries and concussion, it would be a long time before I could withstand any light or go outside. I do remember one of the early days when Christopher visited me. He told someone at MGH that it was a shock to see me. I still had blood on my face, my front teeth were all chipped, and I looked like I’d been hit by a train—after which somebody had finished me off with a baseball bat. I had been outfitted with a brace that fit snugly under my chin and around my neck and was attached to a piece that stretched across my chest and back. I called it my cage.

Another problem began to develop. I started to hallucinate and tried to take out my IV and unhook the cage apparatus, so the nurses had to restrain me with ties. I called both JoAnne and my son and told them I felt there was a plot against me. This was right out of Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

As the week progressed, my body shut down. I could no longer eat and developed aspiration pneumonia. The doctors said I needed to have some form of feeding tube. This was one of the most agonizing parts of my journey. For the next few days, at least four different times, the doctors attempted to insert a tube through my nose into my stomach. It felt like I was choking to death. Finally, after a fourth try, they were successful, but it was only temporary. Ultimately, I was whisked away to surgery, where a feeding tube was inserted directly into my stomach.

After my time at MGH, I spent some often-frustrating days at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital before ending up at NewBridge on the Charles. NewBridge is a combination of a rehab hospital and an incredible assisted-living facility. It was like entering the Emerald City after the tornado. There was a feeling of warmth and laughter, and I could sense my stay would be safe. Most important, I met some of the best human beings—nurses, doctors, and particularly aides. The characters were right out of a great novel.

Most memorable is Virgilio Agustin, who was educated in the Philippines. He was a man of a thousand places and a thousand jokes, none of which was particularly funny but all of which were punctuated by an infectious laugh I’ll never forget. He, along with many others at NewBridge, helped to ease my pain and prepare me for what would be my lifelong journey.

My pain was so debilitating that doctors at NewBridge took me off morphine and started to administer oxycodone until an examination of my stomach contents, done daily through the feeding tube, showed that I was not absorbing the new drug. I was switched back to morphine and then, finally, to the dreaded but necessary fentanyl, which helped with the pain but brought on extreme nausea. Drugs were dispensed three times a day, and I anxiously awaited each dose. In my case, begging at times became necessary.

Because pain ebbs and flows, one’s mental state is very important. Mine was greatly helped not only by Virgilio and the nurses, but even more by the steady stream of friends who came to visit. Bill Martin was there practically every day. I was also visited by Ron Borges, Herald sportswriter and my coauthor on an upcoming history of the NFL, who pleaded, “Please don’t die before we finish the book.”