Banned in Boston: A Brief Tour Through 20th Century Censorship

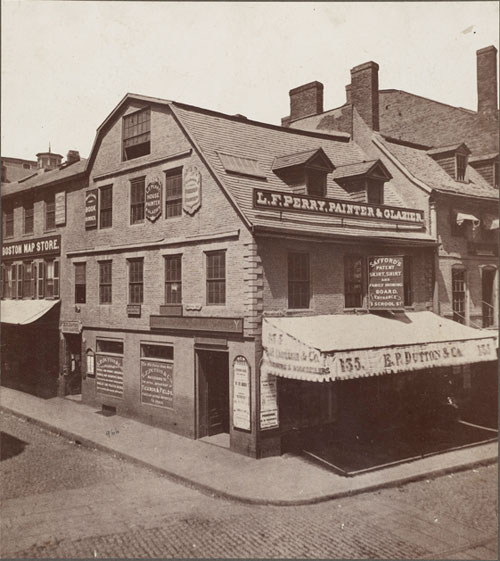

The Old Corner Book Store. (Photo via Boston Public Library on Flickr.)

The Old Corner Book Store. (Photo via Boston Public Library on Flickr.)

Back in the early reaches of the 20th century, a few proper Bostonians made it their crusade to make sure the eyes of their fellow citizens would never see morally questionable material. Their preferred vehicle? The New England Watch and Ward Society, which was under the able direction of Revered J. Frank Chase from 1907 to 1926, bankrolled with great vigor by Godfrey Lowell Cabot.

Today, the legacy of the Watch and Ward Society can be felt in the mention of the phrase “banned in Boston,” which was a badge of honor for many publishers as they waited excitedly to see if their titles would rise the ire of Chase and Cabot. Cabot was a voracious reader and he spent much of his time in his Park Square home looking over the newest books and magazines for anything unseemly. The organization had a type of gentleman’s agreement with the Boston Booksellers Committee between 1915 to 1927, and this was the society’s preferred vehicle for making sure that impure reading material didn’t get into the hands of the average Bostonian.

The history of things that have been banned in Boston has an interesting geography, and it includes a number of sites located within a short jaunt around downtown. This mini-tour will provide the generally curious about the sites associated with this very curious period in Boston’s past:

The Old Corner Bookstore

Located at the corner of Washington and School Streets, the Old Corner Bookstore was the site of an early test case for the powers of the Watch and Ward Society. In 1903, a man walked into the venerable bookstore and asked the clerk on duty if the shop carried any works by Rabelais. The clerk answered in the affirmative, and supplied the man with a copy of The Adventures of Gargantua and Pantagruel (which at that point had been a classic for several hundred years) and went about his business. Several days later, the same man returned accompanied by a police officer, and announced that he was agent of the New England Watch and Ward Society. The clerk was notified that he had sold obscene material to the agent, and he was placed under arrest. The truly unusual thing was that there had been no formal ban on this work, but in the eyes of the Society, this didn’t particularly matter. What was formally the oldest bookstore in Boston now plays host to Chipotle, purveyor of beans and rice specialties.

New England Watch and Ward Society headquarters

The building at 41 Mt. Vernon Street in Beacon Hill was the headquarters of the Society for several decades, and many key decisions were made by Chase and Cabot here about which books, musical performances, and theatrical works might be most deserving of the organizations’ close attention. Cabot was very much the archetype of the Boston Brahmin, and he did not partake of coffee, tea, cigarettes, or spirits. As a young man, Cabot developed a strong sense of what might be questionable in terms of tone and content. His biographer Leon Harris noted that Cabot found The Three Musketeers “coarse and immoral” and later he informed his wife that he was unsure whether the works of George Eliot were suitable for her consideration. In light of Cabot’s vigorous pursuit of questionable works during his life, the discovery of personal letters written by Cabot to his wife by Harris revealed a number of highly lascivious details about his own interests. In one letter, he informed her that he had awoken from a dream in which she had urinated into his mouth, and that she had swallowed it.

The Howard Atheneaeum

Affectionately known as the “Old Howard,” the Howard Athenaeum was located in the heart of Scollay Square. Today, the site of the former theater is part of the massive urban renewal project that transformed the city’s West End and environs, and no trace of the structure remains. Many well-known performers cut their teeth on the stage there, including Abbott & Costello and W.C. Fields. By the 1930s, the perfromances grew bawdier, and burlesque had entered into the regular diet of entertainments at the Old Howard. Never one to pass up an opportunity to regulate morality, the Watch and Ward Society began sending investigators to the theater in the fall of 1932. One show, Facts and Figures of 1932, was particularly offensive to one of the Ward’s minions. In a report he noted that its “viciousness depended more on its homosexuality than on its obscenity.” After a bit more investigative work, the Society brought forth their evidence to the Boston Board of Censors, which included Mayor James Michael Curley. After a summary hearing, the Board of Censors decided to suspend the license of the Old Howard for thirty days. While the Howard did eventually reopen, it was only the third time in the city’s history that any theater had actually been closed down completely.

As I think about it now, banning anything completely in the 21st century is a bit of a stretch. Far-flung servers spew out adult films from around the globe, and even typing in the word “marmalade” into Google might even return some salacious results. Full disclosure: I just typed in “marmalade” into Google and the first result was the Wikipedia entry for marmalade. The second result? The link to the Wikipedia entry for the Scottish pop band of the same name. You’re safe.