TBT: The Final Blast through Hoosac Mountain

After 20 years, 196 deaths, and nearly $20 million, the final stretch of rock was blown away to complete the Hoosac Tunnel in 1874.

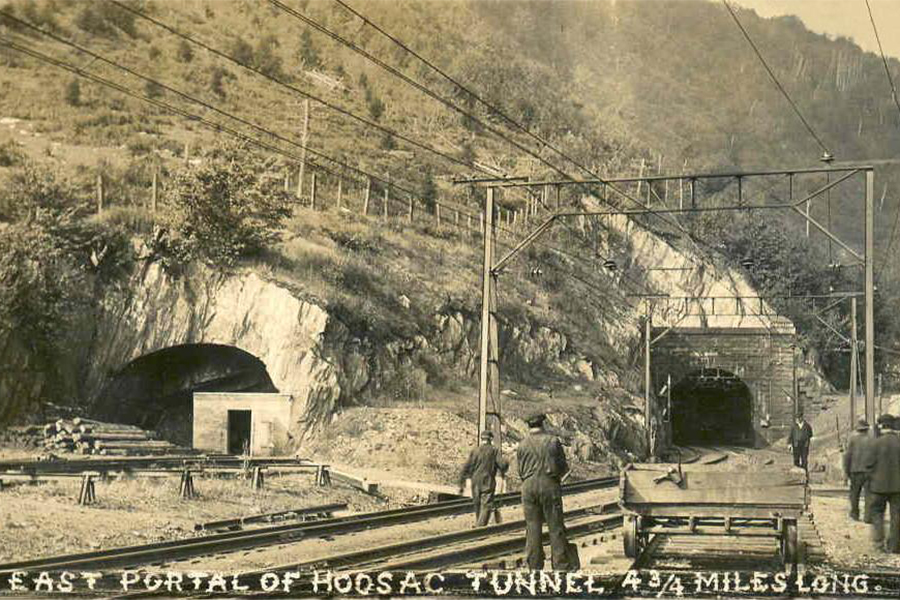

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

As the United States built its economy in the early 1800s, it became apparent to New Englanders that geography was barring them from trade with the rest of the nation. The vast Appalachian Mountain chain, insurmountable by railway and difficult to pass on foot, meanders into Vermont, where it becomes the Green Mountains. The southern edge of these peaks blockaded western Massachusetts from the prosperity of New York and the great frontier. Traders had to go south down the Hudson River Valley, delaying the arrival of progress in northern Massachusetts.

“The people of New England did not, however, sit down behind their mountain wall and suck their thumbs,” reads the December 1870 issue of New York magazine Scribner’s Monthly. “Close business relations with the great West were essential to their prosperity, and they determined to establish and maintain them.”

With true New England grit, surveying for a massive infrastructure project began. At first, a canal system between Boston and Albany was proposed, but the cost was too great. Then, in the 1840s, paper mill owner Alvah Crocker began lobbying for a railroad route to pass through the Green Mountains. Drilling 4.75 miles through a mountain would be no easy task, but the plan was approved. After several years of raising money, in January 1851, the ground was broken and construction of the Hoosac Tunnel began.

Nearly 800 men—predominately Irish and Cornish—began drilling inward from both sides of the mountain, working in shifts around the clock. As the men worked, their families created towns on either side of the mountain. East Camp was located outside the tunnel’s mouth in Florida, Massachusetts, and West Camp was on the other side, in North Adams.

The miners used hand tools to painstakingly drill into the mountainside. Once the hole was roughly two feet deep, it was filled with gunpowder and blasted open. The going was slow: The tunnel progressed only about 60 feet each month, and the project was nicknamed “The Great Bore.” Attempts were made to speed the process, but not all were successful. “Wilson’s Patented Stone-Cutting Machine” was hired for a whopping $25,000 early on in construction, but the massive vehicle faltered after about 12 feet of progress. It remained there for years, and the circular dent it made can still be seen beside the east end of the tunnel today.

In the 1860s, the invention of the compressed-air power drill helped speed up progress, as did the use of the extremely unstable and powerful explosive, nitroglycerin. Still, natural elements hampered miners. The west side was wrought with a mixture of disintegrated rock and water, filling every hole they drilled. Shafts had to be mined to drain the water, and a large portion of the tunnel had to be walled with thick layers of brick. The entire tunnel was given a slight incline from either side—rising just about 20 feet over 2.5 miles—to allow water to run out of the mountain.

Besides the rising financial costs, the tunnel took nearly 200 lives. Accidents and engineering failures weren’t rare, and collapsed supports could be lethal. One of the worst casualties occurred in October 1867 in the tunnel’s central shaft. As the miners dug inwards from east and west, others drilled downward from the top of the mountain, creating a ventilation shaft that would be necessary when coal-burning trains passed through. On the day of the accident, a lantern’s gas fumes ignited, and the ensuing explosion destroyed the hoist used to lower men, equipment, and supplies into the shaft. Flaming materials collapsed onto the workers nearly 600 feet below, killing all 13 men. This tragedy nicknamed the shaft “the bloody pit,” and work ceased for a year. Countless ghost stories of wandering miners have been reported over the years due to the tunnel’s high death toll.

Despite the constant obstacles along the way, the final blast connecting the east and west sides of the Hoosac Tunnel was finally done on Thanksgiving Day, November 26, 1874. Hundreds of public onlookers attended the ceremony celebrating the tunnel’s completion. The entire project took more than 20 years, cost $17 million, and took the lives of 196 men.

Tracks were laid, walls were bricked, and three months later the first train passed through the Hoosac Tunnel—still the longest transportation tunnel east of the Rocky Mountains. Impressively, the tunnel’s path was kept within an inch of the original design through the direction of alignment towers along the mountaintop. For nearly 100 years, passengers and cargo moved with ease between northern Massachusetts and the west, until 1958, when the railway was designated solely for freight trains. Improvements on the tunnel have been made over the years, but its history remains as a testament to New Englanders’ persistence.