No News Is Bad News

Journalism in Boston’s suburbs isn’t just in crisis—it barely even exists. So what happens when no one is minding the shop in the towns where most Bay Staters actually live?

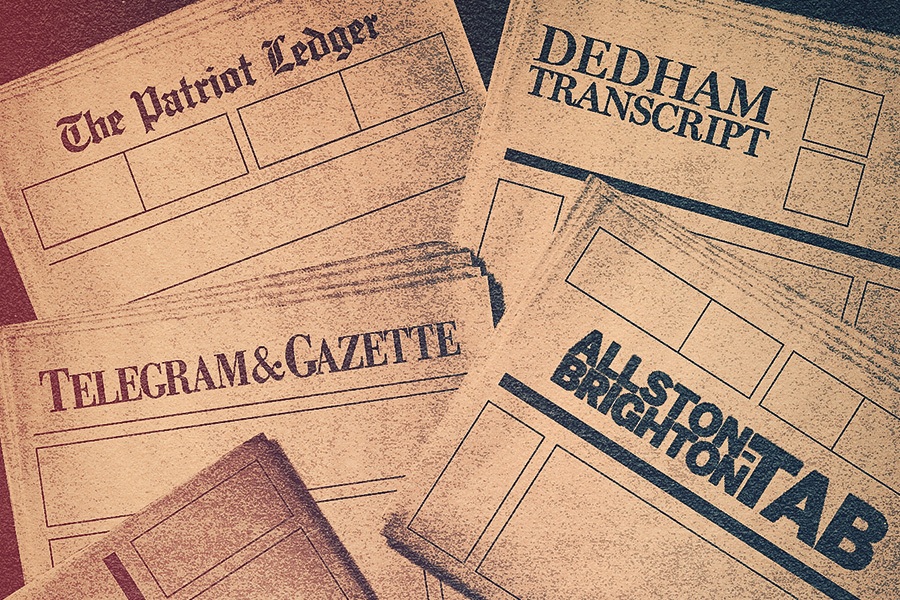

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis

Let’s say that you consider yourself pretty well informed. You read the Globe, not to mention the Times, the Post, or the Journal every morning. Maybe you’re on Twitter or you catch the nightly news, and have a pretty good take on the hot-button topics of the day: climate change, gun violence, impeachment, tariffs. You can even rattle off the names of at least the top half of the Democratic presidential field. But, for the sake of argument, do you think you could explain over cocktails what your local government has been up to lately? Or even who (and no cheating here) is charged with running your little part of the world? Maybe it’s an unfair question. After all, how could you know? Chances are, if you live in any one of the dozens of suburbs outside of Boston, there’s almost no way to find out—your local paper is probably dead.

Most of the time in Massachusetts, if you’re talking about small-town papers, that means you’re talking about GateHouse Media. It owns more than 100 publications here, as part of a total of 600-plus titles across 39 states, and represents the overwhelming majority of papers in the Bay State, including the MetroWest Daily News, Cape Cod Times, and Patriot Ledger in Quincy. Dominance doesn’t mean coverage, though. The story of GateHouse here, and all over the country, has been one of consolidation, layoffs, and cutbacks. The ransacking of local journalism has been going on for more than a decade now—and as editor in chief and co-publisher of DigBoston, I’ve watched it go from bad to worse. Now, we’re starting to see what a world without news really looks like.

Just look at Worcester, New England’s second-most-populous city. As the area embarks on expensive renovations of iconic structures, welcomes a minor-league baseball team, and becomes a booming center for the recreational cannabis industry, there’s more cash—and temptation for graft—than ever. Unfortunately, the city is left without a watchdog. The regional paper of record, the Telegram & Gazette, was bought by John Henry from the New York Times. Henry then sold it to Halifax Media Group, which sold the paper to Gatehouse. The paper eliminated its last long-standing byline, 26-year T&G veteran Clive McFarlane, in August. The arts-and-entertainment-focused Worcester Magazine has been stripped down to a single staffer. Mayor Joseph Petty recently lamented to radio host Hank Stolz, of the bootstrap podcast Talk of the Commonwealth, that “there is no more real newspaper in the city of Worcester.” DIY efforts, such as the 016—a no-frills social media refuge for townies—can hardly be expected to fill the gap.

While the Worcester example is among the most striking, a similar scenario has been playing out again and again in the smaller, wealthier communities around Boston. In June, the Allston/Brighton TAB, West Roxbury Transcript, and Roslindale Transcript all merged. Four South Shore Mariner papers—Abington, Rockland, Hanover, and Norwell—were made into one. And the Dedham Transcript, Westwood Press, and Norwood Transcript & Bulletin all consolidated into a single title. According to an internal GateHouse memo, posted by Northeastern University journalism professor and media watcher Dan Kennedy, the company claimed that the mergers would cut costs “while creating a stronger product for both our subscribers and advertisers.” Even so, the result is that none of the aforementioned publications have a reporter who specializes in any one town.

The damage of these closures and consolidations is nearly impossible to assess—but let me give it a shot. When I queried my network about the impact, responders flagged two kinds of stories that were slipping through the cracks: first, those that haven’t been covered deeply enough, such as defendants who have been denied access to counsel; and second, happenings that have slipped under the radar entirely—from allegations of widespread abuse around recreational-cannabis host agreements to the effects of struggling small colleges on their surrounding towns. There’s no way to know what scoops are being missed as a result of there being nobody out there to find them because, well, you can’t know what you don’t know—but you can make an educated guess.

Why are we talking about this now? Admittedly, the nosedive of local journalism has been a story for a decade or more. It’s because as bad as it is, things here are poised to get even worse: GateHouse is now preparing to absorb Gannett, the largest newspaper chain in the United States, which owns more than 100 dailies, including the Indianapolis Star and the Arizona Republic. The proposed merger has already passed antitrust muster, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, but the looming deal has also spurred additional consolidation in the Bay State, reducing 50 of GateHouse’s titles to a mere 18. Also this year, in apparent preparation for the merger, the media giant laid off 20 percent of its New England–based newsroom staffers—42 out of 212 employees.

In other words, the marriage of GateHouse and Gannett looms like an Angel of Death over what’s left of the local media landscape. Is there any hope of survival? Or are we seeing the last fading rays of light before we plunge headlong into darkness?

When personnel cuts first struck the Patriot Ledger in the aftermath of the 2008 recession, management bought a big cake for everybody in the office to share when a colleague took a buyout or lost a job due to downsizing. By around 2013, though, the discarded workers started piling up faster, two former staffers told me, so to economize, the cakes got smaller and smaller.

This story has been repeated, in one form or another, across the country. (I don’t know if there was always cake, but you get the idea.) According to a February study from the Aspen Institute and the Knight Commission on Trust, Media, and Democracy, “more than 25,000 fewer journalists are working today in communities across the country than in 2007.” Locally, according to research by the University of North Carolina’s Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media, Massachusetts has suffered a 27 percent decrease in the number of daily and weekly newspapers since 2004, and a 44 percent decrease in newspaper circulation during that same period.

Most people haven’t noticed. Nearly three quarters of Americans think their local outlets are doing just fine, financially speaking, and only 14 percent have a paid subscription, according to a Pew study from earlier this year. Eyeballs have migrated to the top tier of national papers: The New York Times and the Washington Post, for instance, each have more digital subscribers in 2019 than they had paid print customers in 2002. But while big juggernauts thrive, there’s almost no one left to mind the local shop. The result is that we’ll continue to see national scandals uncovered, but you won’t have a clue about what’s happening in your own backyard.

At the same time, it’s easy to forget what local newspapers—even those with just an editor and maybe two full-time staff writers—can accomplish. As a study released in August by the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy at Duke University showed, despite the economic hardships that local newspapers have endured, they remain, “by far, the most important source of local journalism serving local communities.” In a study of news in 100 randomly selected communities, local papers represented just one quarter of the outlets, but produced an outsized amount of the content—50 percent of the news and 60 percent of the local stories.

We’re more than a decade removed from a time when even populated, well-heeled towns such as Newton had regular coverage of their city council, school committee, and zoning board. When we notice local journalism now, it’s often because it has uncovered something truly shocking. Take, for instance, the scandals around Mayor Jasiel Correia of Fall River, coverage of which has been dutifully led by the GateHouse-owned Herald News in that city. But big stories are increasingly rare, as workers are tasked with producing as many as 20 short online posts a day. A lot of these young reporters don’t even have editors. Or offices. Given all of that, acts of hard-nosed civic journalism are becoming the exception rather than the rule.

Nothing exists in a vacuum, though, and the collapse of local media has also changed how politics work. Officials today are more often communicating directly with constituents—through email marketing and social media, while bulking up internal media teams in the process—and spending taxpayer money to do it. For instance, in Somerville, which has fewer than 85,000 residents, the city’s proposed 2020 budget designates more than $1 million for “communications and community engagement.” That represents a 17 percent increase over 2019 and includes $250,000 for two communications directors. Compare that to the GateHouse-owned Somerville Journal, where there is one full-time reporter and no editor or newsroom. You may not be paying out of pocket, but I’m here to tell you that you most certainly are paying. Surely, though, there has to be a better way. Right?

On a balmy afternoon in early July, my DigBoston colleague Jason Pramas marched into a crowded, windowless room at the Massachusetts State House alongside a crew of reporters. They weren’t there to cover anything, though—this time, they were the story. The sorry state of journalism had escalated into the sort of crisis that government officials felt compelled to address, as though it were a polluted river or gray-market vape cartridges. Along with contributors and editors from other small publications, journalism professors, and members of the public, my colleagues were there to testify about a proposed bill to form a Massachusetts journalism commission that would study what ails the industry. Still, Beacon Hill probably won’t be what saves journalism.

I know this because, in addition to publishing DigBoston, I spend most of my time trying to find new ways to do the reporting that small papers often can’t. Along with my partners, in 2015 I founded the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism (or BINJ, pronounced “binge”) to support DigBoston, as well as other small and independent news sources that lack the resources to spend weeks, or even months, on an article. The team at BINJ has worked on everything from long-form arts-and-entertainment pieces with KillerBoomBox, a Boston-based black music site, to a multi-part investigation into the lack of oversight in weapons procurement by Massachusetts State Police, which ran in multiple outlets, including a translation in the Spanish-language weekly El Planeta. We have won a few awards, trained journalists from various backgrounds, and even helped other bootstrap media operations start up in Massachusetts, as well as in states as far away as Arkansas and New Mexico. Our mission is pretty simple: teach journalists to make media on their own and create networks that help them help each other. Soon there may be no other feasible option if there is to be any local reporting at all.

What we’ve learned so far is that if you want to be informed, it’s going to cost a premium. As unfortunate as I find this development, the days of solid, free online news articles are largely over. The Boston Globe has retreated behind a pricey paywall—one that’s significantly more expensive than the Post and the Times. This spring, the Boston Herald, which was bought in February 2018 by the notorious strip-miner Digital First Media, quietly began to charge its online readers. Even GateHouse has erected paywalls on its Wicked Local sites.

That’s unfortunate, because paywalls don’t just restrict access to news, they also steer coverage toward communities where their subscriptions are clustered. As if to underscore that point, in August the Globe and Boston University announced they had formed a partnership to bring more hyperlocal headlines to Newton, one of the most expensive suburbs in the commonwealth. But the Globe can’t take on the mantle of covering every town meeting in the state, and no one should be rooting for it to.

Where does that leave us? I’ve spent the past four years trying to sound alarms about this crisis and inspire the public to act, and I’ve seen scant improvement. The destruction of the area’s journalism infrastructure, to say nothing of the deep bases of knowledge that make local papers so essential, is devastating. It’s a loss that likely won’t be properly reckoned with until it’s far too late. What’s missing now is money to do the reporting that still needs doing, and GateHouse, while they argue they’re keeping the lights on and the presses cranking, is hardly the steward we need for the tasks ahead.

As for the proposed state commission, the initial committee makeup was severely flawed. Instead of larding the commission with non-journalistic appointees who will have to play catch-up, officials should have designated more seats for working reporters—and we’ve told the legislature as much. Later, the commission’s lead House sponsor, Lori Ehrlich, indicated that she was amenable to improving its roster. If the state finds a way to start signing checks to fund local independent journalism in the near future, it may yet prove to be a worthwhile endeavor.

In the meantime, the great shame is that there are important stories out there and we’re missing them. In the suburbs, where GateHouse owns nearly all of its newspapers, overtaxed journalists stretched across several beats in multiple municipalities will do their best to uncover what they can. They might even break a big story, despite all that’s working against them. Meanwhile, all around, the wheels are turning, decisions are being made, and people are getting away with things.

Do you know about it? Probably not.

A previous version of this story incorrectly stated who the New York Times sold the Worcester Telegram & Gazette to. The Telegram was first purchased from the New York Times, along with the Globe, by John Henry. Henry then sold the Telegram to Halifax Media Group, who sold the paper to Gatehouse.