The Last Days of Whitey Bulger

His reign as South Boston’s deadliest mobster is the stuff of legend. His time behind bars before being murdered has remained unknown—until now. Read on for an excerpt from Hunting Whitey.

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis

It’s never news when an aging retiree leaves the cold confines of Boston for the dry, warm climate of Arizona, but Whitey Bulger was no ordinary retiree and he was going to no ordinary place. After a lengthy trial at the Moakley federal courthouse, a jury had found him guilty, and now the convicted mobster and murderer was making a one-way trip from his Plymouth cell to the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn. Following a quick stay there, he would be shipped to the federal transfer center in Oklahoma City before finally landing in early 2014 at the United States Penitentiary in Tucson, Arizona. He’d never see his beloved Boston again.

Bulger loved the Southwest and had traveled there extensively while he was on the run. But this time he wouldn’t get to visit Tombstone or the Painted Desert. Sentenced to two consecutive life terms, he’d never again see the outside of a prison. The U.S. Penitentiary in Tucson housed 1,552 inmates in its high-security facility, and few were deemed more high-security or high-profile than Bulger. But he was 84 now, and the years he’d spent in jail before and during his sensational trial had taken their toll. His newfound regimen of daily push-ups helped, but his body and mind were slowing down. Not even the notorious Bulger could defeat Father Time. During his

first few days as an inmate, Bulger befriended a young convict named Clement “Chip” Janis.

Janis had been incarcerated in Tucson for two years before Bulger walked into his life. By then, Janis had committed himself to doing his time and pursuing a career as an artist when he got out. The warden was so impressed by his talent that he put Janis in charge of the prison art room, where he taught oil painting and charcoal sketching to other inmates. One day, while Janis was putting the finishing brushstrokes on several uncompleted projects, Bulger strolled into the art room with his customary gray sweatpants, white shirt, and white baseball cap to inspect the work. Janis specialized in Native American art, so there were a number of paintings of tribe members in traditional dress. Bulger was a huge fan of Native American art, and he took his time studying each piece quietly without disrupting the artist’s concentration.

Janis was vaguely aware of who Bulger was. When Bulger first got to Tucson, prisoners from the East Coast marked his arrival with whispers and surrounded him like hungry sharks. “Oh my God, is that him?” some inmates would ask. But to convicts from the western United States, the geriatric former crime boss wasn’t even the most infamous inmate in the yard. Also housed in Tucson was Brian David Mitchell, the man who kidnapped and raped Elizabeth Smart; former U.S. Army private Steven Dale Green, who was one of five American soldiers who gang-raped a 14-year-old Iraqi girl and then murdered her family; and high-profile Colombian cartel boss Diego Montoya Sánchez. “Some old guy is trying to make friends with me, says he was in Alcatraz,” Janis told a guard. “Yeah, that’s Whitey Bulger,” the guard replied. “He was the mobster who was on the run.”

It didn’t appear that Bulger had made any friends in Tucson, so he began hanging around the art room with Janis, and soon their conversations would spill over to the yard.

“How’d you manage to stay on the run all those years?” Janis asked him.

“They thought I was outta the country when I left.” Bulger shook his head and laughed. “There were sightings of me overseas, but that never happened. I was right there in front of ’em the whole fucking time.”

As the two men sat on a bench in the prison yard, Bulger’s menacing stare constantly shifted, watching every prisoner who passed by. He’d count how many times they’d walk by and then get up to confront them.

“Hey, what’re you doing?” he would ask in a stern voice. “I’m trying to have a conversation here; you walked by a few times. What’re you doin’? You wanna ask me something?”

Bulger understood that he was a high-level target for any prisoners looking to make a name for themselves, and he expected that someone would take a run at him sooner or later.

“When they give it to me,” he told Janis, “I hope they give it to me quick, because I gave it quick.”

Four months after he arrived in Tucson, Bulger’s luck almost ran out when he was jumped by another prisoner, who went by the nickname “Retro.” Bulger was headed to Janis’s art room when Retro, a well-known heroin addict, rushed him and stabbed him in the skull and neck with a homemade knife. The wounds were nearly fatal. Bulger was rushed to the prison infirmary, where doctors worked desperately to stop the bleeding. Somehow, even at the advanced age of 84, Bulger was strong enough to survive the assault.

Bulger stayed in the infirmary for more than a month while Retro was tossed into solitary confinement, which had been his goal. He needed a way to avoid the prisoners he owed drug money to. “[Whitey] sent me a note telling me that he would be fine and for me to say hello to everyone,” Janis says. “I laughed because he didn’t have any friends—just me. But he was showing that he had the prison wired and that he could get things to me.”

While in the infirmary, Bulger sought counseling from a female prison psychologist. He was falling into a deep depression as he longed for his girlfriend, Catherine Greig, who was incarcerated at Waseca Federal Correctional Institution, a low-security women’s facility with 643 inmates in Minnesota. The young psychologist became intrigued by the aging, lovelorn gangster. The two spent hours together, according to Janis. “I get to write to Catherine,” Bulger told his friend after he was released from the prison hospital. “The psychologist came up with some brilliant story so I’d get to write to Catherine. I know the woman’s grandmother. She was from South Boston.”

It didn’t take long until someone at the Tucson prison complained about the relationship between Bulger and the psychologist. Officials began investigating whether she had slipped Bulger a cell phone that he used in prison and if she sold autographed photos that Bulger had given her. “He was the master at charming people,” Janis recalled. Former federal prosecutor Brian Kelly agreed. “It’s no surprise that he’s been breaking the rules and trying to manipulate the system,” Kelly told the Globe at the time. “He’s been doing that his whole life.”

Before long, Bulger was sent packing to the humid confines of the Coleman Federal Correctional Complex, a massive facility about 50 miles northwest of Disney World in central Florida. Bulger’s health steadily deteriorated shortly after he was housed in an adjacent 555,000-square-foot complex known as Coleman II. Like USP Tucson, it was deemed safe for informants and gang members. He began to write to his friend Janis right away. Bulger’s night terrors, induced by LSD experiments that he had been subjected to in the 1960s, were creeping back and making it impossible for him to get a good night’s rest. After midnight, over two nights in early December 2014, he picked up a pencil and crafted a letter to Janis: At 85 years now, don’t have too much more time—especially as every time I turn around something else is wrong with my health…. Come what may, I consider I had a good life—a great family…. and what could be termed adventures along the way.

Bulger also shared his feelings about Greig in other letters to Janis, in which he even stated that he was willing to die for her: Catherine + I on the run for 16 years that flew by too fast. We were together night + day and never had an argument or cross word. But years of our lives were taken from us after capture and both put in isolation. Her, no bail and had no police record…. I offered if they would free her that I’d plead guilty to all charges and will accept execution and no appeal. I will opt for fast track for execution in one year (to save them $$$ + time). She has never hurt anyone—her only crime was loving me.

At the penitentiary in Florida, “When I first saw Whitey, I didn’t realize he was Whitey,” former Coleman II inmate Nate Lindell recalled in a column published by the Marshall Project. “He looked like a pale, white-haired geezer in a wheelchair. Probably a chomo [child molester], I thought. [I] couldn’t see him robbing a bank, killing people, or any other respectable crime.”

One day, while Bulger was napping in the prison yard, an inmate known for selling used shoes tried to steal Bulger’s sneakers right off of his feet. “Hey, stop that,” Lindell shouted. “He ain’t dead yet!” The prisoners all laughed and Bulger went back to sleep.

Bulger was an easy mark at Coleman II, and although he wasn’t beaten up by the sneaker thief, the incident hurt his pride. Had the prisoner tried that even 10 years earlier, he’d surely be dead. But Bulger was defenseless now. Even worse, he was a joke.

After the sneaker incident, Bulger was placed in solitary confinement for allegedly masturbating in his cell. He was caught by a guard while making his rounds at 3 a.m. Sexual activity of any kind was forbidden at the prison. Bulger claimed that he was innocent of the lewd offense, telling prison officials that he was merely applying medicated powder to his genitals to soothe an itch he was too embarrassed to report to the medical staff. “I never had any charges like that in my whole life,” Bulger stated in his disciplinary report. “I’m 85 years old. My sex life is over. I volunteer to take a polygraph test to prove my answer to this charge.” As he wrote to Janis: Frustrating to think I’m in a place where anyone can make an accusation against you and it sticks. Never had this feeling before in any prison—can’t shake feeling that I’m somebody’s target. Kind of a mystery to me—Why? Revenge?

In the end, prison officials didn’t buy Bulger’s excuse and placed him in solitary for 30 days, revoked his commissary privileges, and confiscated his personal property from his jail cell.

By early 2018, Bulger’s health was getting worse. At 8:45 a.m. on February 23, he was taken to the medical office complaining of chest pains. The prison’s assistant health services administrator, Shanna Mezyk, checked his vital signs and performed a cardiac test. It was clear to her that Bulger was experiencing severe cardiac complications. “We need to bring you to the prison emergency room,” she told him. But for some unknown reason, Bulger refused to go.

“You’re treating me like a dog,” he complained. “You’ll have your day of reckoning and you will pay for this. I know people and my word is good!” Mezyk reported the threat to Coleman warden Charles Lockett. Bulger was soon charged with making an implied threat to an employee.

Bulger claimed that Mezyk was lying. He told Coleman officials that he asked the nurse to supply him with a long-sleeved shirt for the visit to the ER and that Mezyk started harassing him over it. He argued that the “day of reckoning” comment meant that she was inducing him to have a massive heart attack because she was yelling at

him so much. “It was all blown out of proportion,” Bulger argued. “I didn’t threaten her.”

Bulger was found guilty of the violation on March 16, 2018, and sentenced to 30 days in “DS”—disciplinary segregation. To the infamous mobster who had spent decades terrorizing his South Boston neighborhood, it was yet another blow—but nothing compared to the fate that awaited him at his final stop on the prison circuit, where karma would catch up with him once and for all.

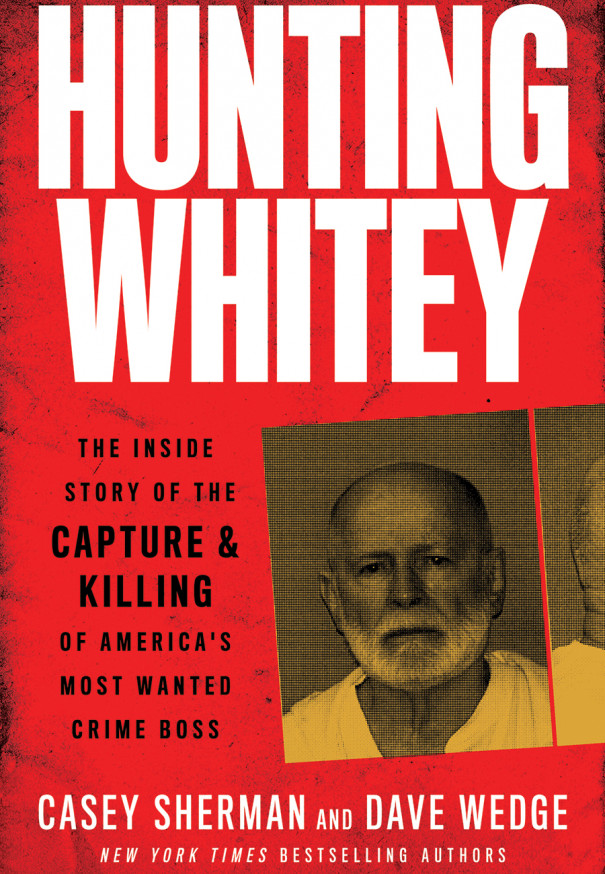

Casey Sherman and Dave Wedge’s book, Hunting Whitey, was released on May 26 by William Morrow, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.