How Has Boston Gotten Away with Being Segregated for So Long?

It’s not as simple as you might think.

Photo via ThePalmer/Getty Images / Photo illustration by Benjamen Purvis

When Sheena Collier moved here from Atlanta 16 years ago to pursue a master’s at Harvard Graduate School of Education, she was looking forward to getting her degree from one of the most prestigious universities in the country. What Collier was not looking forward to, however, was living in the Boston area. Collier, who had just graduated from the historically Black Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia, had the very distinct impression that there weren’t a lot of people of color here.

For her first two years in the area—during which she lived in Cambridge and Allston, interned for a while in Charlestown, and went out at night in downtown Boston—Collier didn’t see anything that changed her mind. Then she moved to Roxbury and began managing after-school programs there. “That was when my whole perception of the city shifted,” she says. “You start to learn that this is who lives in this neighborhood and this is who lives in that one. Boston is diverse—it’s just really segregated.”

Recognizing that a lot of Black people who move to Boston have shared her experience, in 2019 Collier decided to set up an organization, Boston While Black, to help connect Black professionals who were new to the area. Today, she gets calls from people who move to town only to find out they are among the few people of color living there. “A lot of people join the organization because they are just trying to figure out where all the Black people are,” she says.

The first part of that answer is: in Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan. While there has been some disbursement of the Black population in recent decades, an estimated two-thirds of Boston’s Black residents still live in these three neighborhoods. The second part of the answer is: not in the suburbs. Of the 147 municipalities that form the Greater Boston area, 61 are at least 90 percent white and some are much whiter, according to 2017 data. Winchester and Hingham, for instance, recorded an estimated Black or African-American population no greater than 0.5 and 0.6 percent, respectively, in the most recent five-year data from the American Community Survey.

While Boston itself has certainly become less divided by race over the years, it is still nowhere near as integrated as it could be. Today, there are 10 census tracts that have a white population of 88 percent to 97.7 percent in a city that is majority minority. In the time since Collier moved here, in fact, Boston has built a new neighborhood from scratch, the Seaport, that’s almost entirely white. The result? Of the country’s 51 greater metropolitan areas with large Black populations, Boston ranks 15th for segregation. And as of the most recent census, in 2010, the so-called index of dissimilarity for the racial distribution of Black and white people in Boston was 69, meaning that 69 percent of Bostonians would have to move somewhere else within the city for it to have an even racial distribution of Black and white people (any city with an index over 60 is considered highly segregated).

Now, as part of Boston’s racial reckoning in the wake of George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis, activists are not only insisting on police reform, but also renewing demands to address the city’s residential segregation. Over the years, “there has been some movement, but we are so abysmally segregated that a little bit of progress doesn’t mean it’s good news,” says Tom Hopper, the director of research and analytics at the Massachusetts Housing Partnership, a public nonprofit organization. “These patterns are so completely entrenched that the tools we currently have to…drive racial or economic desegregation are inadequate to do the job.”

There are some who attribute the divisions largely to economics rather than discrimination, saying that anyone who has the money, no matter their race, can move to a community like Lincoln. But these beliefs, says Robert Terrell, a Tufts University lecturer and the fair housing, equity, and inclusion officer at the Boston Housing Authority, ignore the fact that housing discrimination still exists and the fact that the city’s wealth gap is largely due to decades of highly deliberate, racially discriminatory housing and lending policies. “People use a number of arguments to try to gloss over how we got here,” Terrell explains. “Perhaps they just don’t want to admit that both the private sector and public sector created the situation we are in.”

Homeownership is one of the greatest drivers of wealth accumulation in this country, and it has also been the greatest engine of inequality. When we look at the now infamous and deeply embarrassing statistic from a 2015 Federal Reserve Bank of Boston report showing that the average white household’s wealth in Greater Boston is $247,500 and the average Black household’s wealth is $8, we have our housing system to point to. Even if we were to wave a magic wand and dispense with the stubborn remnants of a discriminatory housing market and our individual conscious and unconscious biases, these vast economic inequities, largely created by past policies, would keep segregation running on autopilot in perpetuity. “People need to understand the answers to: How did we get here? What were the causes? What role did my government play? What role did I play in it? And how did I benefit from it?” says James Jennings, professor emeritus of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts. “And this will be very controversial in some circles because people will want to say, ‘Well, I worked hard and that’s why I am here.’ Well, that’s where maybe we need to look at history.”

In other words, Jennings and other experts reason, when Bostonians understand how much intention went into segregating our city, they will understand just how much effort will be needed to fix it.

Three siblings in 1938 getting ready to move into New Towne Court public housing complex, a whites-only, federally funded project that was built in an area of Cambridge that had been previously integrated. / Photo courtesy of the Cambridge Historical Commission, Cambridge Photo Morgue Collection

Amos A. Lawrence was a wealthy Bostonian, cotton merchant, and philanthropist who dedicated the later years of his life to funding the anti-slavery cause. He shipped arms to anti-slavery forces in Kansas, where the town of Lawrence now bears his name. He is practically unknown, however, for something he did in 1855 that was truly historic in a far less admirable way.

That year he sold a property in Brookline, wedged between Beacon Street and the Muddy River, to a man named Ivory Bean. The deed said that no structure could be erected on the property “for occupation by any negro or negroes nor by any native or natives of Ireland.” Because this language was included in the deed itself, it applied to all subsequent sales of the property, not just to the original buyers. It’s a mystery why an abolitionist would include such a clause, but it was the first known time in the history of the United States that a racially restrictive covenant was included in a property deed.

Around that time, Boston’s Black community-which consisted of 1,900 people, or about 3 percent of the city’s population-lived primarily in the West End, the North End, and on the northern slope of Beacon Hill. Toward the end of the century, many Black families had moved into the South End, where they lived side by side with white neighbors, before also taking up residence nearby in Lower Roxbury. This covenant ensured that as the area’s Black population grew and expanded, that parcel in Brookline, just a half block from the Boston line, would not be on their route.

It is not known how widespread covenants like these were in Massachusetts, although even today they are occasionally discovered in deeds that were carelessly copied over from the original. However, racial segregation was well under way in Boston as far back as the mid- and late 1800s, according to Brown University professor of sociology John Logan, who says at that time it was most likely the result of individual decisions not to sell or rent to Black people. Segregation of the more formal, legally binding kind found in covenants like the one in Brookline did not catch on in a big way until after 1917, when the Supreme Court ruled that racial zoning laws were unconstitutional around the same time that Black people began leaving the South in droves during the early years of what would become known as the Great Migration.

These covenants weren’t the only way Black families were discriminated against in the housing market. In 1926, the officers of the Boston Real Estate Exchange—an earlier name for the Greater Boston Real Estate Board that exists today—took out a hammer and nail and affixed to the wall of their new headquarters at 7 Water Street a framed copy of the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ Code of Ethics. Toward the end of the document was Article 34, which had just been added two years before. It read: “A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.” Due to popular demand, the Exchange printed up frameable copies of the code for its members to pick up and display on the walls of their agencies, too.

In 1927, the national association went a step further, drafting up a model restrictive-covenant document to share with boards around the country and encouraging them to help form homeowners’ associations that could adopt these covenants. The model covenant said that no part of the property should be used, occupied, sold, or leased to Black people, unless they were servants, janitors, or chauffeurs living in basements, servants’ quarters, or a barn or garage in the rear.

In other words, what started out as a one-off in Brookline eventually became the most widespread means for segregation around the country. But the real estate industry would not be the sole driver of the process in Boston for long. Its notion of a segregated city got a big boost from the federal government.

The Orchard Park public housing complex in Roxbury, shown here in 1986, was segregated by race when it opened in 1942. / Photo by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Sarah Flint moved to Roxbury at the height of the civil rights movement, but inside the Orchard Park public housing complex, it was as if time was standing still. Flint lived on the side of the housing project designated for Black people and never set foot on the other side, which was designated for white people. “I never saw cotton, but I saw the signs in the South that said ‘whites only’ or ‘Blacks only.’ I saw how they treated us,” she says of her trips to visit relatives in Alabama, where she was born. “Boston wasn’t any different—it was just covered up.” Flint lived in Orchard Park until 1990, raising her four children in the complex, one of whom, James “Jimmy” Flint, was killed there at age 15 in front of his best friend, the musician Bobby Brown. Despite the fact that the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968 with the goal of eliminating housing discrimination, public housing in the city remained highly segregated by race until the end of the 1980s.

In fact, the segregated existence in which Flint and countless others lived goes back much farther than the 1960s: It was a stubborn remnant of a system established with great intention by the federal government through a New Deal program to fund the construction of public housing in the mid- to late 1930s and after World War II. In Boston proper, the U.S. government bankrolled the construction of 25 public housing projects, most all of them segregated by race—either by project or by sections of a project. “The Boston Housing Authority was the city’s largest landlord,” says Lawrence Vale, a professor of urban design and planning at MIT. “It controlled 10 percent of the rental housing stock. These projects became a symbol and a signal of racial segregation.”

The segregation in federally funded housing projects wasn’t limited to Boston proper: In 1935, about 100 families, both Black and white, were evicted from a 160,000-square-foot tract right near where Kendall Square lies today, their homes razed to make room for what would be the first public housing project to open in New England: New Towne Court. Three years later, on a snowy January day, after the movers had unloaded tenants’ possessions at the opening, that same section of Cambridge was 100 percent white, and Black people were not allowed to live there. The federal government had taken an integrated neighborhood and segregated it.

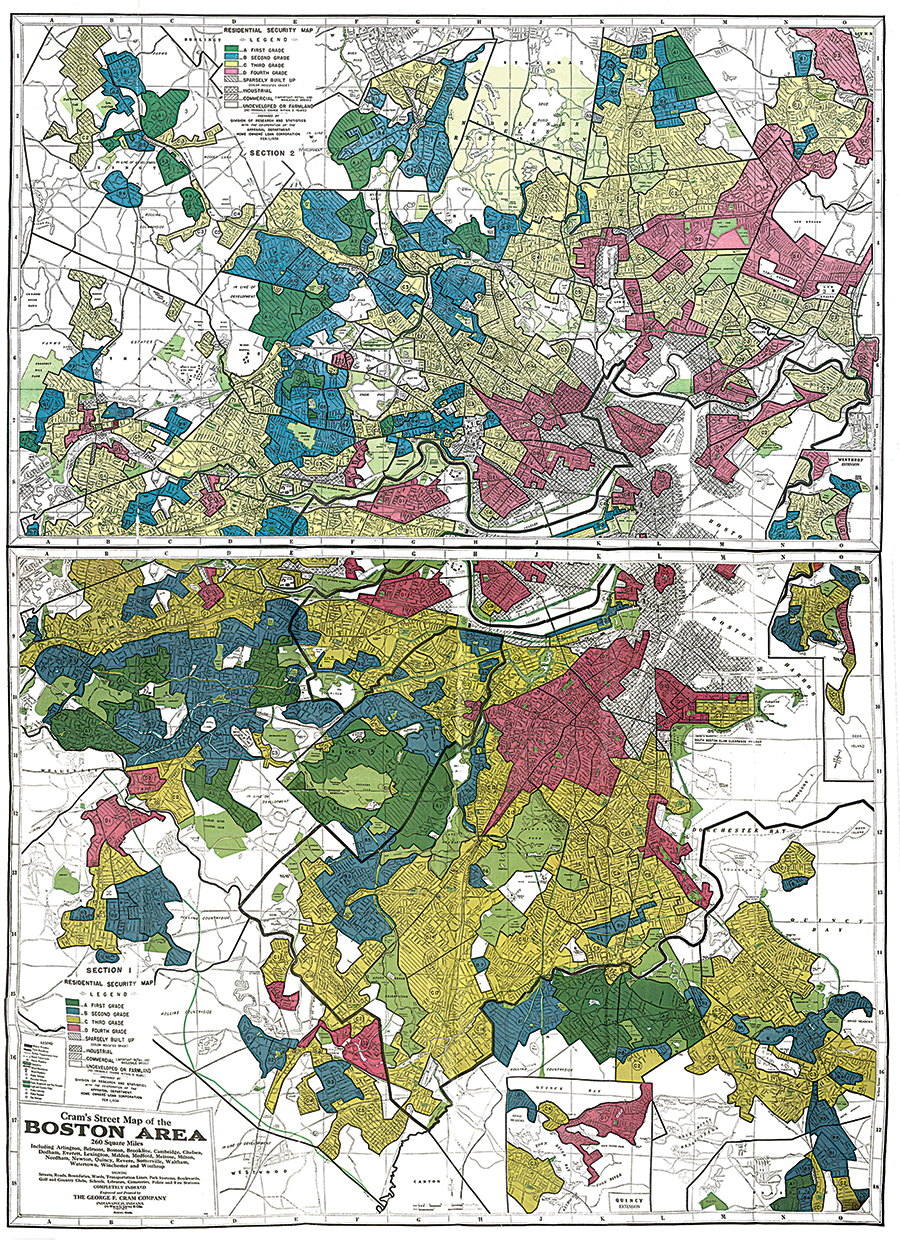

This wasn’t the only, or the most far-reaching, U.S. government policy that ensured Boston remained a segregated city. In 1933, the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was established to refinance Depression-era homes in danger of foreclosure. In order to better gauge risk for these mortgages, the HOLC designed a uniform and highly detailed system of neighborhood appraisals in major cities across the nation, breaking them up into small segments, rating them, and color-coding them on a map based on whether appraisers believed they were likely to increase or decrease in value. Among the main criteria for sorting areas into these categories were the race and ethnicity of their inhabitants.

The result in Boston? Despite the fact that the HOLC acknowledged a section of Roxbury had good transportation, schools, and proximity to jobs, the agency gave it a “hazardous” rating, coloring it red due to the “infiltration of negros.” A neighborhood in Cambridge that had some “high class apartments” received a “definitely declining label” and was colored in yellow, because, as the notes detail, “A few negro families have moved in on Dame St. and threaten to spread.” In a Milton neighborhood, where notes include a comment that there was only “one negro family,” the HOLC granted the area a “still desirable” rating, and colored it blue, while a stretch of Jamaica Plain that had zero Black residents and was only being infiltrated by “desirables” got a “best” rating, and was colored green.

These government maps proved highly influential among private-sector mortgage lenders, who routinely declined to finance homes in red and even yellow districts, giving rise to the concept and the name of “redlining.” This, in turn, not only locked Black people out of homeownership but also ensured that white people had a financial interest in keeping them out of their neighborhoods. It was outside the city, however, in the newly forming suburbs, that the segregationist bent of the federal government left perhaps its greatest and most enduring legacy.

Created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, this 1938 map of the Boston area used race as a key criterion when designating risk for mortgage lenders in neighborhoods, giving rise to the term “redlining.” / Photo via University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab/Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al., “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed.

During the Great Depression, as the nation’s industrial output slowed, an unprecedented number of Americans found themselves jobless, hungry, and, in the worst cases, out on the street. The economy needed a boost—a big one. So in 1934, the U.S. government established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in a gambit to breathe life into the construction industry and get people back to work. It did so by insuring mortgages made by private lenders for new home construction, meaning there was no risk for lenders—any mortgage that went south would be covered by the Treasury.

Along the way, the FHA revolutionized the mortgage market so lenders could offer long-term loans, with down payments of no more than 10 percent, that were fully amortized, allowing homeowners to accumulate equity while still paying off the loan. (In 1944, VA loans, as part of the GI Bill, were also established with similar terms but no required down payment.) These changes also resulted in loans with lower monthly rates, making it cheaper for many people to buy than rent. What ensued was a suburban home-building spree the likes of which no one had seen before.

Since the feds were insuring the loans, they got to dictate lending criteria. The FHA had a marked preference for single-family houses, set back off the road, with yards—the kinds of houses that could be built only in the suburbs. Federal and state grants for the construction of Route 128 also helped speed the growth of the suburbs by making it feasible for people who worked in Boston to live in areas inaccessible by public transportation.

Because the FHA believed that property values would diminish if Black people moved into a neighborhood, its underwriting manual provided a guideline stating that “properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes,” and the agency routinely declined to insure developments that weren’t exclusively white or were too close or accessible to Black neighborhoods. Until 1950, the FHA also encouraged the use of racial covenants to ensure these new white neighborhoods stayed that way. A 1941 newspaper ad for a new FHA-approved real estate development in Wellesley obliquely referenced that it was an “established restricted community,” which could have been referring to an agreement about what color the homes could be painted, or what color people were allowed to live there.

The results of the program were staggering. Across the United States between 1934 and 1962, $120 billion worth of FHA-insured homes were built, and white people were the beneficiaries of more than 98 percent of them. In Massachusetts between 1935 and 1962, the FHA insured more than 68,000 loans worth more than $695 million, contributing to explosive population growth in the suburbs. From 1940 to 1960, Sudbury quadrupled in size, Dedham grew by 150 percent, and Wayland nearly tripled. In 1960, however, they had a total of 22, 23, and 11 Black residents, respectively. With the exception of Cambridge, by 1970 all of Boston’s suburbs were about 98 percent white.

Meanwhile, the steady flow of white people leaving Boston for the suburbs—some 13 percent of that population between 1950 and 1960—coincided with the height of Black migration to Boston. Between 1960 and 1965, the influx of Black people moving to the city represented what was possibly the nation’s greatest internal migration at the time, pushing Boston’s Black population past the 100,000 mark, or nearly 17 percent of the total population. Virtually none was able to capitalize on the benefits of the federal incentives or subsidies being offered to white people, nor get in on the ground floor of a wholly unprecedented opportunity in America to build home equity and wealth.

Rather, they were hemmed into increasingly overcrowded neighborhoods in the South End, parts of Dorchester, and Roxbury, where banks weren’t lending for home improvements or purchases and where the housing stock was shrinking. “Buildings got older, were split into smaller dwellings, and slumlords had a market there because they didn’t have to do anything to maintain them,” says Brown University’s Logan. “So the concept of a Black neighborhood as a bad neighborhood comes right out of that process. They were made to be bad neighborhoods. And neighborhoods that didn’t have any Black people were made to be better neighborhoods.” Put another way, the federal government’s maps became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

On the morning of July 31, 1968, a group of well-heeled Boston bankers stood before the storefront façade of a brick building in the heart of Roxbury’s Dudley Square and cut a ribbon to officially open the Boston Banks Urban Renewal Group’s lending office. “We will provide mortgage money under the FHA program for low-income families who have been unable to qualify for home loans previously,” announced Joseph H. Bacheller Jr., the silver-haired president of Suffolk Franklin Savings Bank.

The initiative had been set in motion by Boston Mayor Kevin White just a few months before, following riots that swept through Roxbury the night Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in Memphis. Sensing the moment was ripe for change, White had decided it was finally time to reverse decades of mortgage discrimination and offer a pathway to homeownership for Black residents—and believed that the city’s business sector was terrified enough after the riots that they just might go for it. He was right. At the same time, the FHA, facing a reckoning for its own past discriminatory policies, got on board to insure the loans issued under what was known as B-BURG.

At the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the initiative he’d sparked, however, White was conspicuously absent. It might have been because he had already seen the writing on the wall: His administration had made it clear that the mayor’s involvement in the program was contingent upon the banks’ commitment to issue loans for properties in the suburbs, too. Fearful that such a move would tank property values of entire neighborhoods, threaten their portfolios, and infuriate their suburban clientele, the bankers wouldn’t commit and eventually made other plans.

Less than a month later, in mid-August, Suffolk Franklin Savings Bank vice president Carl Ericson, who was largely responsible for the program, made the unfortunate choice of pulling a red marker out of his jacket pocket to delineate the program’s territory of operation. He approached a giant map on the wall and traced a line around sections of Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan that corresponded almost precisely with the location of a 40,000-person-strong Jewish community, and determined that the program would lend only inside the line. With the long, winding stroke of a red marker, Ericson had ushered in an era of reverse redlining in Boston.

The decision soon proved equally as destructive as redlining. The instant availability of the $29 million that B-BURG had set aside to finance home purchases was like tossing chum into waters teeming with commission-hungry real estate sharks. It didn’t take long for the so-called blockbusting to begin among the dozen or more agencies that opened for business in the designated neighborhoods following the establishment of the program. According to an agent operating in the area, who went on to anonymously publish his “confessions” in a real estate journal in 1987, the goal was to get as many houses on the market as they could using any means possible. Bald-face lies were not only excused, but encouraged.

According to the confessional, real estate agents would call white residents in areas where Black people were starting to settle and tell them that they better sell because property values were dropping a thousand dollars a month due to the new arrivals. Another tactic was to explain that recently released rapists were about to move in next door. “How would you like it if they raped your daughter and you have a mulatto grandchild?” they’d ask the white homeowners. Some agents got into speculating, buying homes at under market value from white people they induced to sell in a panic and selling them to Black families for far more than they were worth.

Agents weren’t the only ones profiting from B-BURG. According to a 1971 Justice Department civil suit, the FHA’s own head appraiser in Boston, Joseph Kenealy, made $350,000 off the program. Kenealy’s family members bought homes, which he then “appraised” at two or three times their value, allowing them to be sold at inflated prices to B-BURG beneficiaries.

The buyers, however, did not make out so well. Many borrowers had loans that were already underwater the day they moved in. What’s more, the properties were all supposed to be inspected prior to closing, but this rarely occurred, according to Lew Finfer, codirector of the Massachusetts Communities Action Network, who has worked in the area as a housing activist since the 1970s. Many families had to sink money into costly repairs and soon fell behind on their mortgage payments. Because the lenders had no incentive to shore up these government-backed loans, they foreclosed far faster on these properties than those with non-FHA-insured mortgages, quickly collecting their money from the feds.

The outcome? By 1974, nearly half of the people who got loans through B-BURG had lost their homes, which sat vacant for years, attracting vandalism and crime. “The ramifications of the deterioration and the abandonment lasted throughout the ’70s and well into the ’80s,” Finfer says. “It got to the point that in 1974 there might have been an estimated 1,000 abandoned buildings in the B-BURG operation area. It is hard to imagine something of that scale.”

The urban blight in the wake of B-BURG accelerated the white flight that was already under way in these neighborhoods. “In 1968, Mattapan was majority Jewish and minority Irish Catholic, but it was a predominantly white area, about 85 to 90 percent. Within a few years it was 85 to 90 percent African American,” Finfer says. Just a few years later, Boston’s mandatory busing program began and white people continued to stream out of the city until the suburban-urban divide was past the point of no return.

Jacqueline Langham, now 77, remembers that era well. In 1970, the church where her husband served as pastor bought a synagogue in Dorchester from a departing Jewish congregation. Soon, however, her congregation’s new building was surrounded by nine foreclosed homes. “Those abandoned homes were used for drug activity and those people started terrorizing the people who came to our church,” Langham recalls. In an effort to stop the crime, the city razed the buildings, but it didn’t help: Groups of men instead hid behind the mountains of rubble and sprung out to assault passersby. It wasn’t until the early 1990s, when Thomas Menino was mayor, she says, that the neighborhood began to recover.

By the time the B-BURG program ended in disgrace in 1972, there were no official initiatives keeping Black people to restricted zones of the city. Racial covenants were no longer allowed to keep anyone out of the suburbs, and federally funded segregation was a thing of the past. All that was left behind were ideas about Black people and the neighborhoods in Boston they should inhabit.

The city’s projects, for example, remained highly segregated even into the late 1980s, not because of any official Boston Housing Authority (BHA) policy, but because of the way it managed its waiting lists. When Black applicants tried to apply for vacancies in white projects, BHA officials would discourage them from doing so by telling them they would not be safe there and that the housing authority could not protect them, according to a lawsuit the Boston branch of the NAACP filed against the BHA.

Nadine Cohen, who represented the NAACP, believed that once public housing was integrated, private housing would follow. Things didn’t turn out as she expected. After the BHA was forced to integrate the white projects, Black families had bricks thrown through their windows and feces smeared on their doors. In one particularly horrific case, white residents tied Black children’s hands behind their backs and then lit firecrackers in their jacket pockets.

Meanwhile, the suburbs were finding other ways to keep their towns the way they liked them: Thanks to the state legislature’s 1966 passage of the “home rule” law, individual municipalities gained much greater control over zoning policy than exists in many other U.S. metropolitan areas, and passed exclusionary rules that required large lots and prohibited multifamily housing. These policies effectively did the job that racial covenants had done before them: They ensured through zoning that homes would be out of the financial reach of Black people who had not benefited from decades of wealth building through home equity, says former state Representative Byron Rushing.

Real estate agents had long ago taken down the racist code of ethics from their walls, but Cohen says that multiple studies and audits from the late 1990s and 2000s revealed that agents, without saying or doing anything overtly racist, often gave white people more information and showed them more homes in more towns than Black buyers. It still happens. A recently published Suffolk Law School study used people posing as renters to conduct 50 tests. Among their findings: Real estate agents discriminated against the Black testers 71 percent of the time by telling white testers that more units were available, showing them twice as many units, and offering them more incentives to rent.

The area’s Black population has continued to face mortgage discrimination, too. Studies from the 1980s through today consistently show that Black people get fewer mortgages than white people with equal income, which means they continue to lose out on the opportunity to buy homes, build equity, and accumulate wealth. In fact, the only time since B-BURG that Black people finally became the recipients of mortgages at an unprecedented rate was in the late 1990s and early 2000s, during which time they were disproportionately targeted for subprime mortgage loans even when they qualified for conventional ones. As a result, the fallout from the subprime crisis was felt more strongly in Boston’s Black communities. “There were over 4,000 foreclosures in Boston between 2006 and 2011, and more than 80 percent took place in Boston’s historic neighborhoods of color,” says Lisa Owens, executive director of City Life/Vida Urbana, a tenant advocacy group. What followed was a torrent of evictions and the displacement of Black families.

This set up Black neighborhoods for a wave of gentrification in the wake of the crisis, when homes throughout Boston’s Black neighborhoods where working-class families once lived were bought up by real estate investors and resold to higher-paying homeowners, Owens says. A recently released study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition found that nationwide, between 2013 and 2017, Boston ranked third for gentrification.

This process is perhaps the greatest irony of the saga of segregation. People who were once forced to live in certain Boston neighborhoods are currently being forced out of those places now that they’re seen as desirable in the eyes of white people. Many displaced Black families who are not doubling up with other families in crowded living spaces are leaving the city altogether for more affordable places such as Brockton, Fall River, New Bedford, and Randolph. As Rushing says, “Black people have given up on Boston.”

There is no shortage of plans and policy proposals that could help Boston and its suburbs become less segregated. But to turn those bright ideas into lasting change, we’ll need something more: a commitment to take on this debt to our Black community and invest in reversing the harm of decades of housing discrimination. When we talk about integration, it is important not to become enamored with shortcuts, nor to lose sight of the fact that “integration is not a pathway to social justice; it is a result of social justice,” says David Harris, the managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School.

The Boston Foundation, city officials, and many other housing activists say it is high time for suburban communities—many of them filled with progressives who support Black Lives Matter—to drop their exclusionary zoning policies and allow for the construction of more affordable housing in their towns. Doing so, proponents say, will not just expand the area’s housing stock, stemming the rise of home prices in Boston proper, but would also enable more people of color to move to the suburbs.

While Chapter 40B, known as the “anti-snob zoning act,” has established that 10 percent of cities’ and towns’ housing stock should be affordable, many people, including Governor Charlie Baker, believe municipalities have to do more. Baker is currently trying to get a law passed that would allow local zoning decisions about affordable housing projects to pass with a simple majority rather than the two-thirds approval currently required. The federal government under Barack Obama also showed interest in promoting affordable housing with a 2015 rule that required towns and cities receiving U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development funding to identify potential fair-housing issues—including segregation—and address them. This year however, President Donald Trump tweeted that he had rescinded this policy. “I am happy to inform all of the people living in their Suburban Lifestyle Dream that you will no longer be bothered or financially hurt by having low income housing built in your neighborhood,” he wrote. “Enjoy.”

Even if suburbs were to open their doors to lower-income residents, though, Tufts lecturer Terrell wonders why it is that Black people are the ones who always have to move. In fact, he says, the constant drumbeat about the advantages of living outside the city smacks of bias by holding up the white suburban lifestyle as the gold standard to which Black people should aspire. Many Black people don’t feel welcome in the suburbs, nor do their kids feel welcome in suburban schools. Terrell, for his part, lives in Roxbury and says he doesn’t want to live anywhere else. He is not alone. Recent studies show that Black Bostonians live in poorer neighborhoods than their white counterparts of equal income do. Some of this is due to ongoing discrimination, but some of it may well also be preference.

That’s why Terrell says it’s important to ensure that Black residents can continue to afford to live where they want while enjoying opportunities there that are equal to those in white suburbia. To make that happen, housing activists say, Boston needs to reinvent the way it thinks about urban planning, among other things. It isn’t enough to be nondiscriminatory; according to City Councilor Lydia Edwards, policies must actively seek to repair the harm from decades of discrimination. The city and developers can’t simply “plan for new housing in the city and then advertise to communities of color that they are welcome in the new housing and say therefore we have done our jobs,” she says. “It’s laughable, but that is the fair-housing policy of the city of Boston right now. That is exactly how you end up with a neighborhood like the Seaport.”

Edwards, for her part, is trying to head off another Seaport in East Boston. When it seemed like the project to develop the Suffolk Downs racetrack—the largest private development in Boston history—was careening toward the mold of another white, wealthy enclave, the city councilor helped negotiate several impressive concessions from developer Thomas O’Brien of the HYM Investment Group. She says O’Brien agreed to include more affordable units, define “affordable” at a level that more closely mirrors the local neighborhood, and make these affordable units larger in order to accommodate families. What’s more, the site will adhere to Edwards’s proposed new equity standards that she is working to get accepted into the city’s zoning code.

Edwards’s proposal, which the mayor has signaled he is willing to sign, would be the first of its kind in the nation, ensuring that city planning occurs through a fair-housing lens. If passed, it would demand that the real estate development industry, which was so instrumental in segregation, assume responsibility to help the community heal, she says.

In a profit-driven world, though, any effort to right the wrongs of the past will require no small amount of public funding to ensure that enough affordable housing gets built. Unfortunately, according to Sheila Dillon, chief of housing and director of neighborhood development for Boston, the feds under Trump have reduced funds available to cities for affordable housing, and a couple of proposed policy changes that would enable Boston to collect a fortune by increasing real estate transaction fees have been marooned at the State House. “We are doing everything we can at the city level,” Dillon says, “but we really do need state and federal partners.”

Let’s hope they get them. After all, if this annus horribilis has taught us anything, it is that legions of Bostonians believe that Black lives matter; that when we are faced with an emergency like the pandemic, we are willing to make personal sacrifices for the greater good; and that, when necessary, the government can come up with a lot of money really fast. As we look forward to a fresh start in 2021, there’s never been a better time to undo the segregated city that took so many resources to create in the first place.

Note: Due to mistakes in multiple secondary sources, the original version of this article incorrectly identified the source of the racially restrictive language as an earlier Brookline deed from Thomas Aspinwall Davis’ 1843 development of the subdivision known as “The Lindens.”