Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King in Boston: A Love Story

Separating fact from myth in the Kings' love story.

Photo by David Briddell

There are two photographs of Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta, that paint a vivid picture of their time together in Boston. Captured in the Public Garden months before they would head to Montgomery and take their place on the world stage, one is of the couple alone. In the other, they are joined by MLK’s BU classmate David Briddell and his then-fiancé, LaVerne Weston, who, like Coretta, was studying voice at the New England Conservatory.

Dressed to the nines, the two couples stand on a footpath halfway between the George Washington statue on the western side of the Garden, and the lagoon footbridge, a stone’s throw from the bench Matt Damon and Robin Williams made famous in Good Will Hunting. The blooming bed of tulips at their feet signals it’s April, the high western sun on their faces confirms it’s afternoon, and the wedding band on Martin’s hand resting on Coretta’s shoulder makes it 1954, 10 months after they exchanged vows the previous June.

Photo by David Briddell

From all indications, Martin and Coretta are happy and content, the picture of married perfection. But reaching this point in their Boston journey, and finding each other, did not come easily. They were each facing their own personal challenges before their arrival in the city in September 1951.

There has been no shortage of myth-making involving the life and times of MLK, and his Boston love story with Coretta is no exception. A prime example of this surfaced recently, as veteran journalist Katie Couric hosted a ‘virtual’ celebration of Boston Preservation Alliance’s 32nd Annual Preservation Achievement Awards this past October honoring laudatory renovation projects around town. That’s when award recipient Boston University claimed its renovated Myles Standish Hall in Kenmore Square marked the spot where “Martin Luther King met his wife.”

“It’s folklore, but I think it’s based on truth,” said retired BU assistant vice president Marc Robillard in a prerecorded interview. “There was an event—it might have been in this very room—that Coretta Scott was singing at, and Martin Luther King was here,” he said, noting the school’s desire to keep and preserve this message and history.

The truth is Robillard and BU had the right couple, but the wrong campus. Martin and Coretta met, in fact, on a blind date across town at the New England Conservatory of Music in January 1952, under cold wet midday skies. And to be sure, she wasn’t singing. “I waited for him on the steps outside the conservatory on the Huntington Avenue side,” she wrote in her 1969 autobiography, My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr. “The green car pulled up to the curb, and as I walked down the steps, I could see the young man sitting in the car.”

BU’s faux pas, however innocent, illustrates the temptation of self-insertion when it comes to compelling historic narratives. It also speaks to how unmined the couple’s Boston history—from 1951 to 1954, during which time they lived here as students and first met—really is. And it underscores that this city, widely regarded as the home of the American Academy, should know better, and do better, in its awareness of the basic facts of two of its most famous former residents. With the 70th anniversary of the couple’s arrival in Boston and the unveiling of a world-class monument to them fast approaching, now is as good a time as any to set the record straight on the Kings’ years here.

Martin Luther King Jr. arrived in Boston heartbroken, after schoolmates at Crozer Theological Seminary outside Philadelphia, where he had been studying, urged him to break up with his longtime girlfriend, who was white. They insisted Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he was to succeed his father as pastor, would never accept Elizabeth “Betty” Moitz as its congregation’s “first lady.” Heeding their advice, King headed to BU alone to earn his PhD. It wouldn’t be his first exposure to New England—he spent the summers of 1944, at age 15, and 1947, at 18, picking shade tobacco in Simsbury, Connecticut, to help pay his way through Morehouse College.

Coretta, meanwhile, had been scarred after racism reared its ugly head in Yellow Springs, Ohio. She was matriculating at Antioch College there when local school officials denied her request to student-teach in their predominantly white classrooms, a requirement of her elementary education and music major. Incensed after college administrators refused to come to her defense, she joined the local NAACP before transferring to the New England Conservatory of Music.

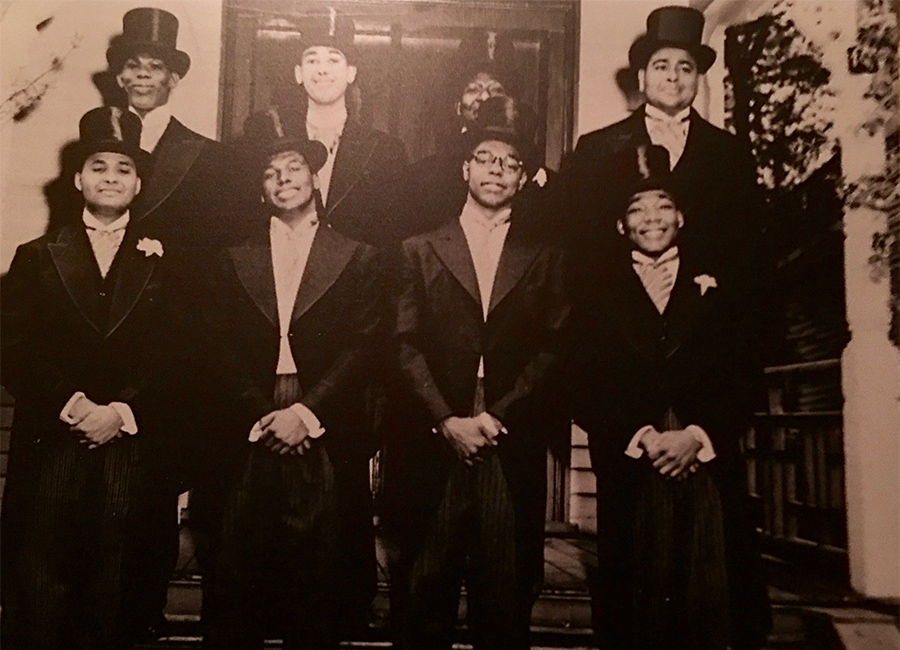

While both Martin and Coretta arrived in Boston gifted, capable, and eager, they did not enjoy the same financial freedom. Martin owned a car, lived in an off-campus apartment, and preached as an assistant minister at the prestigious Twelfth Baptist Church (a successor to the historic African Meeting House on Beacon Hill). He enrolled in classes at Harvard Divinity School, earning credits toward his degree at BU. He was also drawing a salary as an associate pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church back in Atlanta, where his father was pastor. That revenue stream gave him choices, including joining the Sigma Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity in Roxbury, whose members included future U.S. Senator Edward Brooke.

Photo of Martin Luther King Jr. and his frat brothers courtesy Baron Martin, Esq.

The promising Atlanta divinity student made strong impressions everywhere he went. “I just remember him knocking on the front door of my grandfather’s house on Ruthven Street,” recalled the late attorney Herman Hemingway, who pledged with Martin, and posed in a group photo of fellow pledgees on Wabon Street in Roxbury. “I will never forget how Martin introduced himself as a graduate divinity student,” he said with amusement in a 2017 interview at his Waltham home. “He asked us all to refrain from using profanity in his presence.”

Joining a sorority, conversely, was not in the cards for Coretta. Money was so tight she couldn’t go home for Christmas one year. Nearly two years older than Martin, she had arrived in Boston with $15 in her pocket, and a scholarship that covered little more than her tuition and fees at the conservatory. Desperate to make ends meet, she worked as a maid for her landlady, Antioch College patron Charlotte “Cabot” Bartol, a member of Boston’s first family, who rented her a room in her Beacon Hill mansion. When she wasn’t in class, Coretta scrubbed floors, cleaned rooms, did laundry, and, for a time, ate graham crackers, peanut butter, and fruit for dinner. After two and a half months, things improved when the local chapter of the Urban League helped land her a part-time job with a mail order company.

While Martin was gregarious and outgoing, the Heiberger, Alabama, voice major was reserved and guarded. LaVerne Eagleson, now 90, arrived the same fall to study voice at NEC, and met both Martin and Coretta before they met each other. Eagleson (then known as LaVerne Weston) remembered her first impression of Coretta in a recent phone interview from her Salisbury, Maryland, home. “We were in line to pay our fees. I looked around, and everybody was white, and standing right next to me was this Black girl,” she said. “And I said, ‘Oh my goodness. Hi, my name is LaVerne and I’m from Houston, Texas.’” Pausing, the Alabama native’s response was measured: “Oh, I’m Coretta, and I’m from Ohio.”

Despite Coretta’s less-than-warm demeanor and distancing from her Jim Crow southern roots, Eagleson did not think she meant to be rude. “I think she was a little aloof. That was her personality.”

Around the same time, Eagleson also met Martin. “I had come from church and went to a restaurant called the Sharaf’s Cafeteria on Mass. Ave.,” she recalled. “And this guy came and sat at the table across from me, and he kept staring, and decided to pick up his tray and come sit at my table.”

Eagleson went out twice with Martin. Despite admiring the future civil rights leader’s intellect, there was nothing between them. “The thing that stuck with me most about him was that he said that he was going to kill Jim Crow. And I just listened, you know. I said, ‘I wonder, how is he going to do that as a preacher?’”

Coretta and Martin orbited initially in separate worlds in Boston. He lived in predominantly Black South End/Lower Roxbury, while she lived in predominantly white Beacon Hill. He attended church, while she worshiped in her room, since almost all the Black churches had already migrated to Roxbury.

They were two trains running on parallel tracks, with no station in sight. That is, until late January 1952, when a mutual acquaintance intervened. Like Coretta, Mary Louise Powell studied voice at the New England Conservatory. She was also married to the nephew of Martin’s mentor, Morehouse College president Benjamin E. Mays.

Visit the Landmarks of their love story

680 Shawmut Ave.

Formerly Twelfth Baptist Church, where MLK was assistant minister.

170 St. Botolph St.

MLK’s first Boston residence

1 Chestnut St.

Coretta’s first Boston residence, where she earned her room and board working as a maid.

9 Greenwich St.

Former Home of Mary L. Powell, who introduced the couple.

290 Huntington Ave.

The New England Conservatory of Music, where the couple first met.

187 Mass. Ave.

Formerly Sharaf’s Cafeteria, site of the couple’s first date.

397 Mass. Ave.

MLK’s second Boston residence.

558 Mass. Ave.

League of Women for Community Service, Coretta’s second Boston residence.

396 Northampton St.

Formerly Lincoln Apartments, site of the couple’s first home.

Martin approached Mary that fateful January about eligible coeds, prompting her to share Coretta’s name and, later, telephone number. The two spoke and agreed to have lunch between classes the following day.

It was love at first sight for him, but not for her. “My first thought was, ‘How short he seems,’ and the second was, ‘How unimpressive he looks,’” Coretta wrote. Still, Martin picked up Coretta in his green Chevy, taking her from the Conservatory on Huntington to Sharaf’s Cafeteria on Mass Ave., where he turned on his charm.

“You have everything I ever wanted in a wife,” Coretta recalled him saying.

“You don’t even know me,” she responded.

Martin was smitten, and despite any reservations Coretta may have had, he was driven to win her over with his sense of humor, ability to dance, and love of good music and conversation. They became inseparable, going everywhere together. To hear pianist Arthur Rubinstein at Symphony Hall. To attend his sermons at Twelfth Baptist. To ride the roller coaster and Ferris wheel at Revere Beach. To attend a friend’s weekend party in Watertown. Even to go shopping in downtown Boston. “Why don’t you buy that pretty coat we saw in Filene’s?” she recalled him saying.

By the end of her first year, Coretta moved off Beacon Hill and into Martin’s South End/Lower Roxbury neighborhood. She rented a room from the League of Women for Community Service in the South End, while he moved from his apartment on St. Botolph Street to one on Massachusetts Avenue. Less than three blocks separated them now.

Their lives became intertwined. They introduced family members to each other. Coretta’s sister, Edythe, cooked creole pork chops in Martin’s apartment during a visit. Martin’s sister, Christine, a professor at Spelman College, spent her spring break with them. In the fall, Martin’s parents came to town.

Coretta recalled her relationship with her future father-in-law got off to a rocky start. “He’s gone out with some of the finest girls—beautiful girls, intelligent, from fine families,” Martin’s father told her. “Those girls have a lot to offer.”

Still, Coretta held her own, eventually having the last word. The following Easter, the Kings announced the engagement of their son to Coretta in the Atlanta Daily World. In June 1953, a little over a year after that first lunch together, Martin and Coretta exchanged vows on the front lawn of her parents’ home, with Daddy King officiating.

The two spent that summer in Atlanta. Coretta worked as a clerk for a Black bank where Martin’s father was a director, while Martin relieved his father of preaching duties at Ebenezer. They then headed back to Boston for their final year in the city.

Home became a dilapidated six-story former hotel, later known as Lincoln Apartments, that would be leveled in the ’60s to make way for I-95. That is, until protests forced politicians to scrap those plans, and create what is now the Southwest Corridor Park. Their one-bedroom rental was located on Northampton Street and Watson, a block from Mass. Ave. and Columbus, then the epicenter of Black life in Boston. From here, Martin completed his residency requirements and began his thesis.

Coretta, meanwhile, accepted her new role as a preacher’s wife, switching majors from voice to music education, taking a heavy course load, and even practice-teaching in Boston at an all-white high school and two elementary schools. She graduated from the NEC and marched June 15, 1954, at Jordan Hall, on the same block where she first met Martin. Then she headed to Atlanta to spend the summer with her husband’s parents, while Martin stayed behind in Boston to continue working on his dissertation through the month of July.

In October 1954, a month after being inducted as pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, he and Coretta took a train back to Boston, where they spent two weeks holed up in a hotel room, typing his nearly-350-page dissertation. Before they finally left the city, the two paid a parting visit to Twelfth Baptist Church where he had been an assistant minister.

The late Reverend Michael Haynes, who was an assistant minister with King and died in 2019, had a conversation with him and Coretta standing outside the sanctuary. “Martin asked me whether I wanted to come with him,” Haynes shared in a 2018 interview at the former Shawmut Avenue site of the church. “I turned his offer down because of what I had heard about the Jim Crow South. I will never forget that.”

After earning his PhD from BU a year later, Martin was a no-show at his own graduation in June 1955, due to his wife’s pregnancy and his lack of travel money. But just six months after earning his doctorate, Coretta and Martin emerged on the world stage during the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Other battles, accolades, and headlines followed. Albany. Birmingham. The March on Washington. St. Augustine. Selma. The Nobel Peace Prize. The passages of the Civil Rights Act of ’64 and Voting Rights Act of ’65.

He returned to Boston multiple times during those years. To accept honorary degrees. To donate his papers. To friend-raise and fundraise. And to lead a march in April 1965, protesting “racial imbalance in schools,” which some regard as the opening shot of the Boston busing crisis. The march route was a homecoming of sorts, starting at William E. Carter Park—named for a Black military veteran and located a block from the Kings’ home at Lincoln Apartments—and ending on Boston Common.

Three years later, on April 4, 1968, an assassin’s bullet cut his life short at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where LaVerne, Coretta’s old schoolmate, and her then-husband, David Briddell, had stayed only a year before.

All these years later, Laverne reflected on what Martin shared with her when they first met about his life’s purpose: “Rosa Parks just gave him a chance to fulfill his dream to kill Jim Crow, and he did it.”

More than half a century has passed since Martin’s death, and 15 years since Coretta’s. And while Boston prepares to honor their legacy in sculptured, mirrored bronze on Boston Common, its greatest inheritance will be the Kings’ simple story of a love found, a vision shared, and lives lived that changed the world for the better. That is why Boston will forever be holy ground—and no amount of myth-making can cloud, distract, or alter that simple truth.