The Interview: Top Model and Activist Cameron Russell

With a new book out this month, the Cambridge native is looking to transform the fashion industry, one difficult conversation at a time.

Portrait by Mei Tao

Sure, being a supermodel comes with plenty of perks—shoots in Milan, free clothes, an endless supply of cappuccinos—but as Cambridge-raised Cameron Russell writes in her searing memoir about the trials and tribulations of her career, it’s not all Zoolander jokes and smiling for the camera. An outspoken activist since the start of her career 20 years ago, the former Victoria’s Secret runway model cofounded the Model Mafia collective, a network of colleagues working to build a more sustainable and equitable fashion industry and world. Now, ahead of the release this month of her book, How to Make Herself Agreeable to Everyone, she sat down with us to chat about motherhood, life after modeling, and how even cover girls still get pimples—just like the rest of us.

You’re publishing your memoir, but what else comes after modeling?

For me, there’s never really been a before and after, because I started when I was so young. It sort of started as a side gig—I was going to high school, and then I would take the Chinatown bus to New York to work, and then I’d come back and go back to high school. Then I went to college while I did it. I also started a magazine, and I organized artists and activists, and then I realized that actually organizing within my own industry would probably be more effective—I had a big network. All of which is to say that I never really felt like I just did this one thing. I was doing things inside and alongside this work.

Was that the start of the Model Mafia?

Yeah, it became the Model Mafia, but even before that, I was organizing models for about 10 years, trying to affect change inside our industry. I was in college and post-college, during the birth of a ton of movements like Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and the DREAMers. And then I realized, at some point, that it would probably be powerful to show up as my full self and organize my peers to show up with me and figure out how we could bring those movements into our industry and also bring what we understood from our industry into those movements.

You’ve always been political, and you studied political science and economics at Columbia University. Do you see yourself going more and more into social activism?

Well, first of all, shout out to growing up in Cambridge and sneaking into all of those Harvard Kennedy School lectures. That was good encouragement. I snuck into Benazir Bhutto and Noam Chomsky and many lectures that I was not invited to but saw anyway. It truly colored my perspective and upbringing, but I think we’re headed toward a future in which we really have to reckon with the way that politics is affecting our lives in its unwillingness to catch up to human needs.

Has motherhood colored your thinking?

I honestly didn’t really have a before and after, the same way with modeling. I didn’t feel like I was born as a new person the day that I gave birth, except that I was in a new, lifelong relationship. Of course, it’s a change. But one thing that’s oddly similar between motherhood and modeling is that both are a form of feminine work that aren’t taken seriously and aren’t seen as skilled. My experience in mothering and parenting has allowed me to see the ways that the work of sustaining life is work that many, many, many people on this planet do without recognition.

Would you ever allow your child to pursue a modeling career?

I don’t know. Everybody is so different. I think it would depend on why they wanted to do it and what the circumstances were.

Models you admire?

My dear friend Ebonee Davis. She’s a model who has never waited for anybody to cast her in their story or on their cover. Since the very beginning of her career, she’s understood that she wants to speak in a fashion language in a particular way, and she sets up her own productions and produces work that easily rivals what’s happening at Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar—though she does work with those publications, as well. She’s a person who’s really interested in fashion as cultural expression.

Portrait by Mei Tao

How would you describe your book?

It’s a story about working in fashion for 20 years, which in some ways could be seen as a unique experience. When I started, it was more unusual than it is today because of social media. Now, everybody’s a model, right? Everyone has to think about their image and how what they put inside this frame will affect them. What opportunities will they have? Who’s listening? I think those questions and concerns are fairly universal.

What would you say is the biggest way that your career has messed with your head?

Well, that’s definitely part of the book: me trying to figure out and be honest about how affected I am—and I think we all are—by fashion. It’s supposed to be this place where we find joy, but in our day, it’s quite disposable. It’s supposed to be a fantasy, so we can’t be in a thoughtful, long-term, critical engagement with it because then it’s no longer a fantasy. But fashion is not separate from the rest of life. It’s afflicted by the same things the rest of the world is, and as it grows as a massive piece of our economy and as we start to realize that rampant consumerism is not the way forward, I think we all have to think really critically about how that affects us.

What impact do you think the fashion industry has on young people, especially girls?

I was listening to my cousins talk one day. They were looking at Instagram. They’re 11 and 12, and one of them said, “Oh, she looks so pretty. It’s too bad because the other person looks so terrible in that photo.” And the other one said, “You can’t say that. That’s not nice.” So there’s something very obvious, even to a child, about how it’s not right to say that one person is more beautiful than another. The place where it gets complicated is that our culture sends the wrong signals in that it celebrates the exceptional success of a very, very small group of women in this industry. If you are one of the women who encounters that success, it’s complicated to figure out. Everybody was telling me that I was successful and to keep on going. And yet it was obvious to me that there was something wrong in how this system works.

What’s the fundamental problem?

As I got older, I had the time and space to research my own industry—and with a degree in economics I better understood what was going on—so I have a much more pointed and clear critique. This is an industry that relies on gendered exploitation and racial exploitation. And as a white woman who’s successful in that industry, that’s a very complicated relationship. I have to figure out how to unpack that and how to constantly be aware of and challenge it the best that I can from the inside.

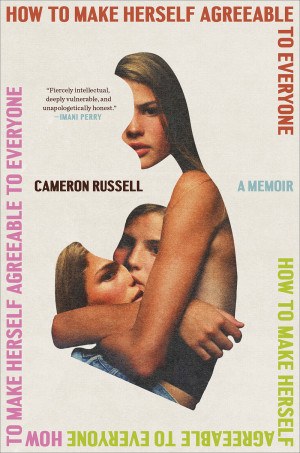

Courtesy Penguin Random House

You use the idea of complicity a lot in your book. Is that what you’re talking about: participating in and benefiting from a system that you have tremendous reservations about?

Of course. Some questions that I get a lot are, “Why still do this work?” “Why continue to engage if there’s an element of complicity, no matter what you do?” And in answering that, I always want to be thoughtful about not being apologetic and be very clear that I think the work I’ve done has done a lot to effectively challenge, change, and evolve the industry. But I don’t think that the industry is separate from the rest of the world.

When you look in the mirror, do you like what you see?

Honestly, when I’m not working, I don’t look in the mirror that much. But it’s incredible how these totally ridiculous concerns can sidetrack us. How is it that a pimple in the middle of my forehead can disturb me when it’s the hottest year on record? But rather than beating myself up, I try to question why I’m even disturbed to begin with. And it must be because something has set this up. Some patriarchal, capitalist system has been set up to make me profoundly concerned about this. We’re living inside this ridiculous system of hierarchy and evaluation.

What would you say your best feature is, and I don’t necessarily mean physical, although it can be if you want?

My friends and my family.

Do you view fashion and modeling as art forms?

They can be. One of the things that my book tries to untangle a little bit is whether there’s a way to be in front of the camera and make images as art and culture or whether it’s always in the service of making money. And I think we’re being asked to answer that question as we see the rise of AI models. Can AI do the job just as well, just as interestingly? If our only reason for making fashion is to make money, then perhaps AI can do just fine, but if we’re striving for something more human—something about culture, something about bodies, and the fact that we speak a language with our bodies—then I think the answer is that AI can’t replace models.

You’ve been extremely outspoken about “fast fashion.”

You know, fast fashion started almost exactly when I started working. I think H & M opened just before I became a model. And during the next two decades, it moved from being more about culture to being more about money. The challenge for everyone in the industry now is to be thoughtful and serious about returning fashion to culture, taking it back from being a purely money-making endeavor.

Who’s doing that now?

So many people, and they’re doing it so brilliantly. I think of Custom Collaborative, a nonprofit in New York that trains low-income women of color to start their own sustainable lines. Angel Chang is a brilliant designer who does carbon-neutral womenswear with a small indigenous community in China. I could go on.

Can you name a moment of pure joy in your modeling career?

Absolutely. There were millions of moments that were wonderful. I remember a time my friend Shannan and I were on some shoot in Milan where they kept offering us cappuccinos. We were working well into the night, having a complete giggle fit. Or shooting for Prada in a dark studio for four days. By the time they got to the TV commercial, the video part of it, I was in such a silly, playful mood, I was crawling across the floor.

Thing you’re most afraid of?

You sound like my younger sister. She loves to ask me existential questions. I’ll say climate change.

How do you feel about the criticism that modeling is a major factor in young girls’ body dysmorphia?

I think fashion is part of the problem there, and we should be critical of and interrogate that and figure out how we can have more diversity both in front of and behind the camera—how we can protect, honor, and respect young girls coming of age in this culture.

What’s the greatest length you ever went to for a shoot, or just something absurd or harebrained?

I’m sure it was doing something in high heels.

What one thing would you tell yourself at the age of 16 if you could go back?

To trust my intuition more. The older I get, the more I find that just because I can’t articulate something clearly, there are still a whole bunch of other signals that I should listen to. Feeling something, just because you can’t name what it is, isn’t a reason to ignore it. And just because you’re not as articulate or as loud as someone else in the room doesn’t mean that what you’re perceiving is not correct.

First published in the print edition of the March 2024 issue with the headline, “Model Behavior.”

Previously

- The Interview: Legendary Philanthropist and Ad Man Jack Connors

- The Interview: Celtics Co-Owner Wyc Grousbeck

- The Interview: Cybersecurity Expert Corey Thomas

- The Interview: Crime-Fiction Writer Dennis Lehane

- The Interview: Novelist Hank Phillippi Ryan