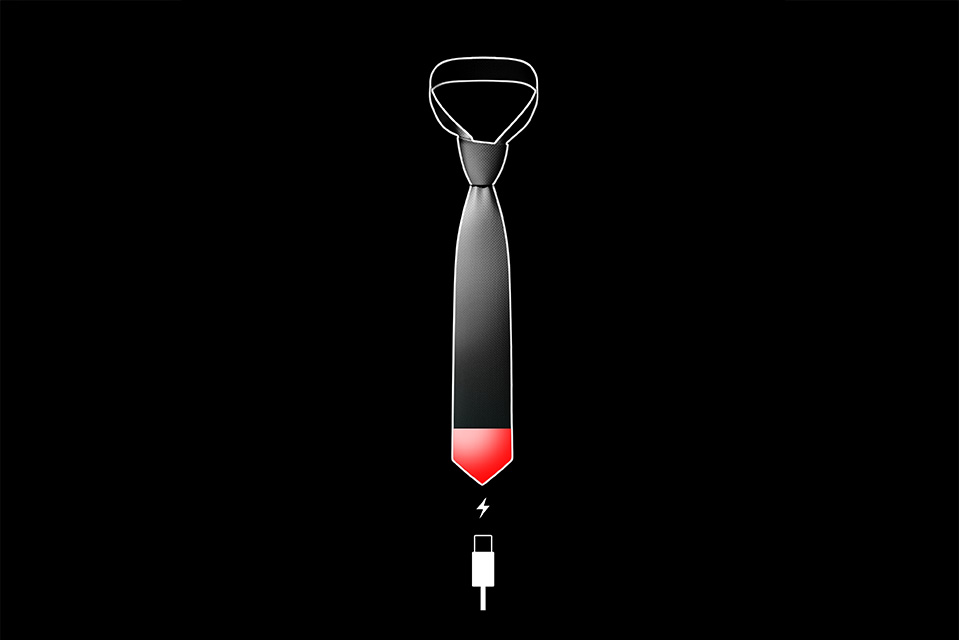

Has Boston Business Lost Its Juice?

The city’s corporate class once saved Boston from bankruptcy. Now, with a fiscal crisis and mayoral showdown looming, the business community faces its biggest test yet—and Boston’s future hangs in the balance.

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis

Of all the trappings of corporate and political spin, none is more ubiquitous than the grip-and-grin. You’ve seen it a million times: bigwigs emerging from the blood-soaked battlefield of negotiation with a show of unity, hands that moments ago were at each other’s throats now locked in a celebratory shake, their forced smiles gleaming for the cameras.

Mayor Michelle Wu’s press release last fall hit every note of this familiar script. With empty office towers and plunging real estate values threatening an unprecedented budget crisis, City Hall faced a crucial choice: slash city spending, hike residential taxes in an election year, or squeeze more taxes from struggling businesses. Her announced “compromise”—negotiated with the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce, Boston Municipal Research Bureau, the Commercial Real Estate Development Association (NAIOP), and Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation—was hailed by Wu as the product of “the strong leadership and partnership from across our neighborhoods and business community.” Chamber president Jim Rooney played his part, declaring he was “proud that we worked with Mayor Wu to reach a resolution.”

Yet private emails from Rooney to members of the Chamber’s executive committee (obtained by Boston) paint a different picture—one of capitulation rather than compromise. Before the agreement was finalized, Rooney had sent the committee an email saying that Wu was “mounting a divisive pressure [and] misinformation campaign…bashing the business community” that was “starting to wear down” the resistance of some members of the legislature. After the compromise, which allowed for a dramatic increase in commercial taxes without any city spending reductions, was finalized, Rooney wrote that he was “not happy,” explaining that Wu had proven “immovable” on spending cuts.

Ultimately, the state Senate blocked legislation needed for Wu’s plan and was still holding her refiling in limbo as this column went to press. But the failure of the business establishment to extract significant concessions from the mayor is a reminder of how far removed they are from the days when the Chamber and other organizations—including the notorious “Vault,” once the city’s most powerful business leadership group—could persuasively flex political muscle and win.

Decades earlier, for instance, Vault members (who advised four mayors—John Collins, Kevin White, Ray Flynn, and Tom Menino) had rallied to help save the city from bankruptcy, and successfully promoted city charter change. In the 1990s, meanwhile, business groups led the charge for a massive public investment to improve public education statewide in exchange for an accountability system anchored by the MCAS test, an evaluation high school students had to pass to graduate.

By contrast, the weakness of today’s business community was on display when, just weeks after its capitulation on commercial taxes, nearly six in 10 voters statewide brushed aside business opposition and voted to drop the MCAS graduation requirement. In the fight over Ballot Question 2, the Massachusetts Teachers Association (MTA) raised the vast majority of the repeal campaign’s $16 million, while the business community, which opposed the measure, mustered less than a third of that—most from a last-minute donation by billionaire media mogul and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a Medford native. “I’m very disappointed in the lack of business community involvement,” Michael Rodrigues, chair of the Senate Committee on Ways and Means, told a business group later in a rare public rebuke. “The silence was deafening.”

It represented quite a comedown for the corporate lion kings whose roars of disapproval once reverberated through the jungle. Today, they’re mostly gone—decimated by out-of-town takeovers, corporate mergers, and retirements—replaced by something far less intimidating and far more decentralized. As the millennium faded, the Vault dissolved, as did the clout and cohesion of other local business advocacy groups, their political muscles atrophying over the years as a string of pro-business governors, legislative leaders, and mayors were on hand to save their bacon.

It was a run of good luck that, in City Hall at least, seems to have run out—and the stakes couldn’t be higher. The voice of business “is significantly diminished compared to my era, and I don’t think it’s a good thing,” says Dorchester’s Larry DiCara, an unofficial city historian who served on the Boston City Council in the 1970s. “When people interested in building in the city don’t get phone calls returned and can’t get a meeting with the decision maker, they take their money and go somewhere else.”

The numbers echo the story of a place increasingly hostile to business. As recently as 2012, then-Governor Deval Patrick was proudly citing Massachusetts’ sixth-place standing in the annual CNBC ranking of the nation’s top states for business—confirmation, he claimed, of “our proven growth strategy.” In the most recent survey, we’re down to 38th, kept afloat by strong showings in technology and innovation as well as quality of life, but a dismal 49th in the cost of doing business. The millionaire’s tax, impending cuts in federal funding affecting our biggest industries—eds and meds—and the continuing exodus of younger workers threaten to bring our state down even lower. And that’s bad news for Boston, with the looming commercial real estate collapse that has the potential to plunge the city into the dreaded “doom loop,” in which plummeting tax revenue, a projected $500 million shortfall, and service cuts further undermine economic vitality.

Now, amid a mayoral showdown that could determine whether Boston remains wide-open for business or faces an exodus of capital, the business community has a golden opportunity to assert its influence once again. Yet at this make-or-break moment, the city’s business leaders seem weaker than ever—raising the question: Has Boston’s once-mighty business establishment lost its mojo?

In 1959, beneath the streets of Boston, a fateful meeting took place that would alter the city’s destiny. In the basement of the Boston Safe Deposit and Trust Company, 14 of Boston’s most influential business leaders gathered with an audacious mission: to rescue their hometown from financial collapse.

The city was on its knees. Boston’s bond rating had plunged to historic lows, and skyrocketing property taxes (sound familiar?) were making businesses increasingly reluctant to invest—or worse, forcing them to flee altogether. The once-proud place had become an emblem of urban decay. Into this crisis stepped Ralph Lowell and his fellow titans of industry—a mix of banking executives, industrialists, and real estate moguls—who believed private enterprise could be Boston’s salvation. Their basement gathering place earned them the “Vault” nickname from the press. The timing was critical. As newly elected Mayor Collins took office, he inherited a city in crisis. The Vault, operating as the Boston Coordinating Committee, became his invisible cabinet, working behind the scenes to rally support for ambitious redevelopment efforts like the Prudential Center and Government Center. What started as an informal gathering of self-appointed advisers expanded to 30 members by the early 1980s, forging an unprecedented alliance between private wealth and public power. For nearly 40 years, while politicians cycled through City Hall, the Vault endured, steering Boston’s economic revival from the shadows. “I know this sounds immodest,” John LaWare, CEO of Shawmut Bank and chairman of the Vault in the 1980s, once said, “but we have an enormous amount of clout.”

The old guard reflected Boston’s glaring inequities—power concentrated among white, mostly Harvard-educated men operating in private clubs. Yet, in the Boston Busines Journal in 1983, political expert Peter Dreier noted that this privileged circle held a common commitment to carving “out an image as a socially responsible corporate citizen”—and they had the financial muscle to back it up. Even after the Vault shut down, when critical issues putting business interests at risk arose, says a veteran of past ballot campaigns, a single meeting of top executives could yield “a guarantee of $10 million.”

Following the economic boom set into motion then, Boston’s corporate landscape experienced a series of unexpected seismic changes—transforming the city’s power structure in the process. Globalization, corporate mergers, out-of-town takeovers, and waves of retirements created a far less centralized network of influence, hollowing out the once-unified business community. Between 1991 and 2011 alone, according to one report, the state lost a third of its corporate headquarters.

The decentralization of Boston’s business class had real consequences, and it became exponentially more challenging for the city to control its own destiny.

This decentralization of Boston’s business class had real consequences, and it became exponentially more challenging for the city to control its own destiny. Having lost many long-standing local leaders, branch managers were suddenly in charge here—often left begging distant CEOs for help with political advocacy that they were typically reluctant to provide. In a 2003 report for Harvard Kennedy School’s Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston, former Bank of Boston executive Ira Jackson, who also served as chief of staff to Mayor White, noted that Boston essentially transformed into a “branch plant town,” and that the “lack of a powerful business voice and agenda has undermined efforts to address a wide range of public issues.” The report stated that while individual executives served on nonprofit boards and supported fundraising, broader business leadership on policy had practically vanished. At the time, corporate giving had favored marketing-friendly sponsorships over local needs—particularly among foreign-owned companies, which research showed gave less locally and focused more on national or global causes.

By the 1990s, the Vault’s influence had shifted to newer business groups, and the organization officially dissolved in 1997. Some still miss its clear business leadership and local control, crediting it with sparking Boston’s renaissance after an era when a fractured business community battled City Hall. Yet many celebrate the end of this exclusive power center, whose all-white Yankee membership seemed increasingly out of touch with Boston’s diversifying population.

The truth is, the days when old-boy bankers could wield unchecked power were numbered a long time ago, their reputation battered by decades of corporate excess, from the “greed is good” 1980s through today’s DC billionaire chainsaw rallies. The public’s trust has eroded accordingly: From 2022 to 2024 alone, the number of Americans who want to hear business leaders’ views on current events dropped by double digits, to below 40 percent.

In Boston, this decline in business clout was laid bare during last fall’s MCAS ballot-question debacle. According to interviews with people close to the situation (most of whom insisted on speaking anonymously), the business lobby’s grossly underfunded campaign to keep MCAS as the graduation standard was hamstrung by conflicting personalities and agendas, with campaign insiders keeping experienced operatives sidelined. Meanwhile, several sources claim the Massachusetts Competitive Partnership (MACP), a Vault-like group that includes big-name executives such as Ronald O’Hanley, State Street chair and CEO; Roger Crandall, president and CEO of MassMutual; and Anne Klibanski, president and CEO of Mass General Brigham, launched an untimely fundraising drive for its new advocacy offshoot, the Mass Opportunity Alliance (MOA), that allegedly impeded fundraising for the fight against Question 2. (Not true, says an MACP spokesman.)

An additional sign of the business community’s discord is evident in another recent MOA controversy. The group—also tied to the Massachusetts High Technology Council and the right-leaning Pioneer Institute—has alienated business leaders with what some saw as an act of clumsiness: an online ad about the $2.1 billion in federal pandemic funds erroneously used by the state government to cover unemployment claims. At first blush, it seemed like a reasonable take: The ad demanded Beacon Hill, not business owners, cover the shortfall, using the slogan “You Broke It. You Need To Fix It.” But one crucial detail was missing: The blunder occurred during Charlie Baker’s administration, not Healey’s. The omission infuriated legislative leaders and Governor Healey, whose team reportedly saw it as evidence the MOA was operating as a stealth platform for Republican Mike Keneally’s gubernatorial bid—he’d just resigned from Pioneer’s board to challenge Healey. Most telling, the MOA’s frontal assault on Beacon Hill broke sharply with the relationship-based approach favored by Rooney and other business groups.

While business groups squabble over fundraising, turf, personalities, and

priorities, their weakened political muscle has created a vacuum—one eagerly filled by left-wing groups like the MTA, backers of the Question 2/MCAS purge, and Raise Up Massachusetts, a coalition of labor unions and their allies behind more than a decade’s worth of increases in business costs, including the 2022 passage of the millionaire’s tax. “It’s nobody’s fault where we are,” says Jay Ash, president and CEO of the Massachusetts Competitive Partnership, the parent of MOA. “We’ve all become complacent.”

Other business leaders, still steaming over MOA’s alleged role in the Question 2 fundraising failure and alarmed by its right-leaning orientation, beg to differ. But the blame game isn’t likely to repair the core problem: A business community that for decades offered a clear, politically effective voice for fiscal restraint and moderate social progressivism is increasingly morphing into a Tower of Babel—and getting its butt kicked by its ideological adversaries. “I’m surprised at everything that’s gone on,” says Katherine Craven, of the Massachusetts Business Roundtable. “All of the organizations are reflective of the membership, and they’re organizationally dealing with their own issues. But things that were once done on a

strictly policy basis have become extraordinarily political.”

Yet in politics, as the old saying goes, to the victor belong the spoils. Faced with what might be the last best chance to derail Wu, arguably the least business-friendly major political figure in the state right now, the business elites are so far standing down.

The stakes may be high for the business community when it comes to this fall’s mayoral race, but so far at least, very few leaders seem to be speaking out—and they might see good reason not to overtly put their thumb on the scales. Take the mayor’s recent clash with the Boston Municipal Research Bureau (BMRB), the staid 93-year-old City Hall watchdog group. When the BMRB, Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation, NAIOP, and the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce retreated from the negotiated compromise after the city backed off inflated forecasts of residential tax increases, Wu skipped the traditional mayoral speech at BMRB’s annual fundraiser and took to social media to dismiss the organization as “a political action committee to lower corporate taxes.” In her own statement, BMRB interim president Marty Walz said, “We are disappointed that Mayor Wu has chosen not to participate in our annual meeting because of a single policy disagreement.”

Still, a path forward exists—if the business community wants it. And some smaller players have shown the way. In 2017, for instance, facing union-backed ballot questions on minimum wage and paid leave, Jon Hurst, president of the Retailers Association of Massachusetts, took “a page out of the playbook of the left-wing advocates,” as he noted the following year. He gathered funds for a ballot question to slash the state sales tax—a billion-dollar threat that brought unions to the bargaining table. The resulting “grand bargain” was signed into law in 2018 by then-Governor Charlie Baker, and won businesses a slower wage-hike phase-in and modified leave requirements. “The entire business community must be more willing in the future to engage, invest, and lead to ensure common sense prevails, and that the Commonwealth remains attractive to employers of all types and sizes,” Hurst wrote.

Meanwhile, in Needham, Greg Reibman’s Charles River Regional Chamber, which also includes Newton, Watertown, and Wellesley, offers a modest model the Boston heavyweights might want to study. Reibman says his group has focused on housing, as it is “critical for economic vitality,” identifying exclusionary zoning as the major barrier to affordable development. Their success in breaking down opposition to a mixed-use development on Needham Street in Newton a few years ago came through coalition-building—“working with housing advocates and environmentalists and local clergy”—the same tactics used by unions and NIMBY groups. The chamber, he says, also trained business owners in “how you talk to municipal boards without alienating the public in general.” If nothing else, it’s an approach that takes business voices out of the boardroom and into the community with a focused, thoughtful message—giving businesspeople a chance to prove they aren’t aloof, greed-crazed aliens.

The stakes are clear. With Wu a prohibitive favorite for reelection and public-sector unions eyeing their next round of tax-raising, power-consolidating campaigns, the business community might want to heed the lesson from that classic children’s song: The more we get together, the happier we’ll be. Or watch from the sidelines while others run the show.

This article was first published in the print edition of the June 2025 issue with the headline: “Has Boston Business Lost Its Juice?”