What It’s Like to Be a Conservator at the Boston Athenaeum

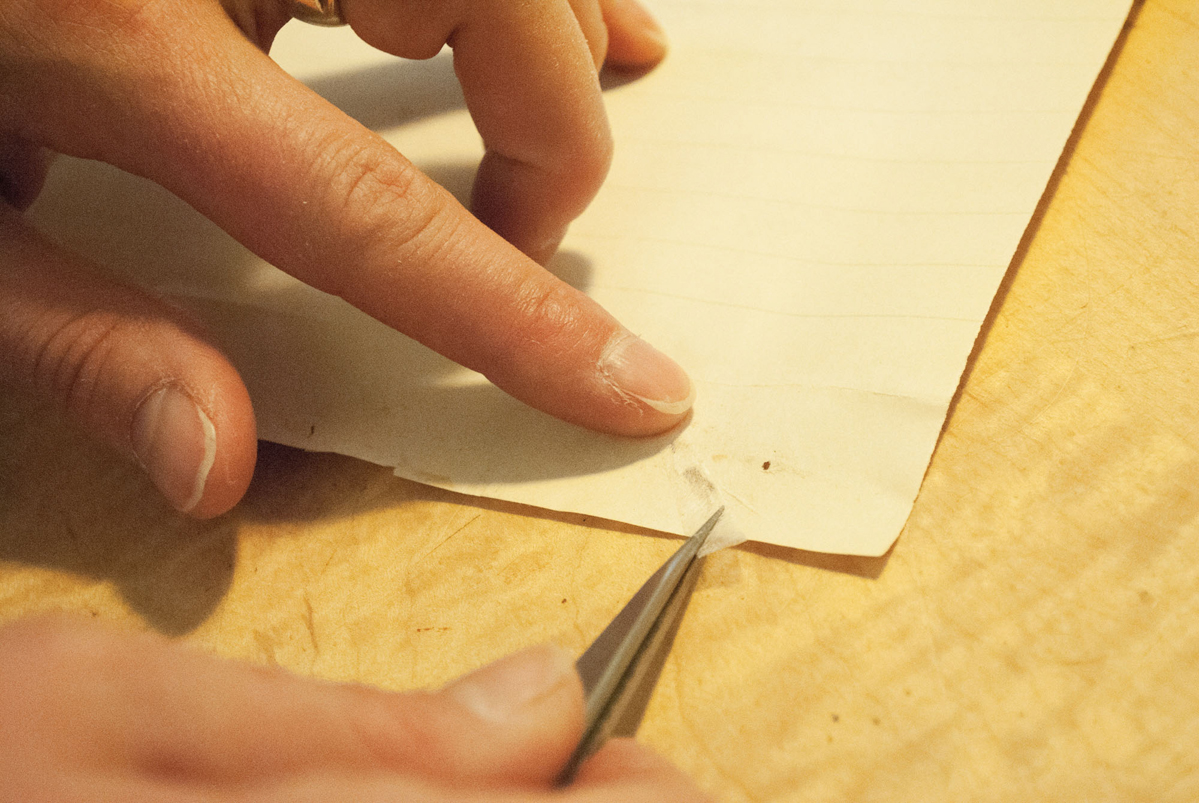

Books to be re-bound sit on a work table. / Photo by Madeline Bilis

Dawn Walus picks up a hefty book.

The cover is tattered and its binding has worn thin. The book, filled with rare atlases, dates back to 1585. She sets the book down on a work table to revisit later in the afternoon.

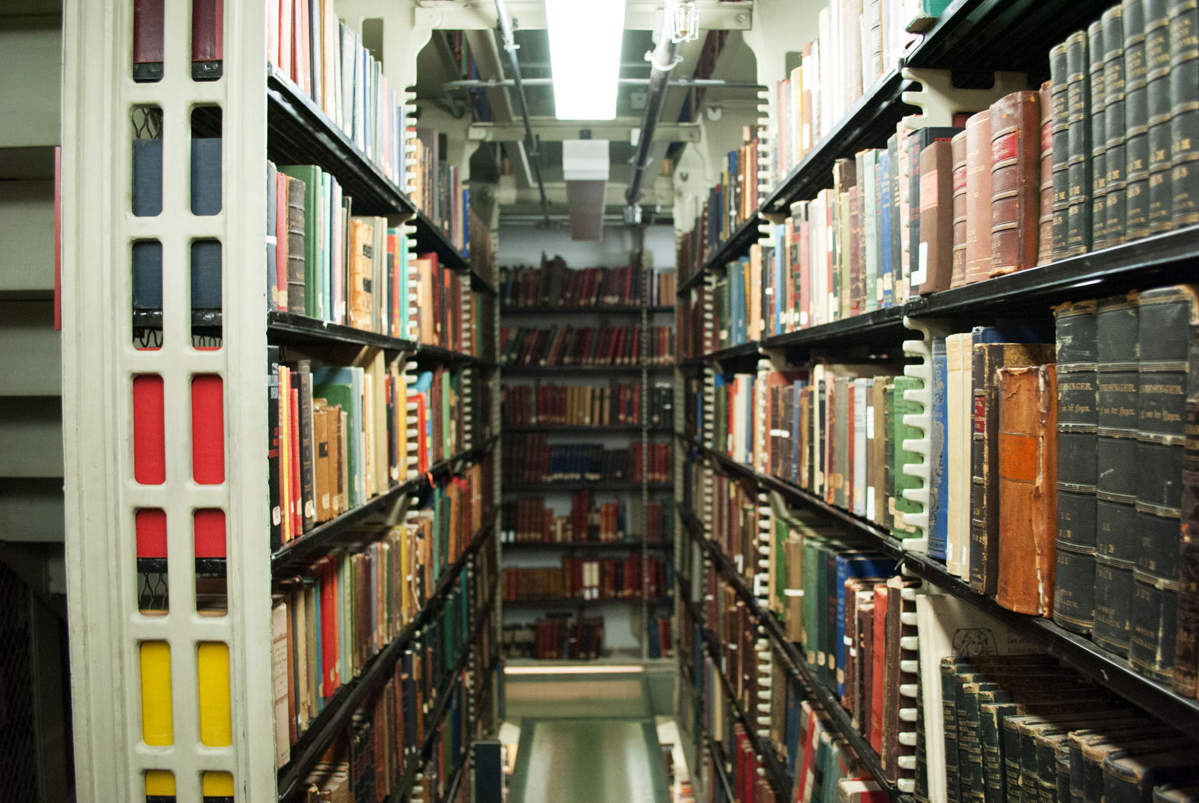

Walus and her colleagues frequently tend to 400-year-old books, maps, letters, prints, posters, and all types of ephemera in a basement laboratory at 10½ Beacon Street. She’s the chief conservator at the Boston Athenaeum, one of the oldest membership libraries in the country.

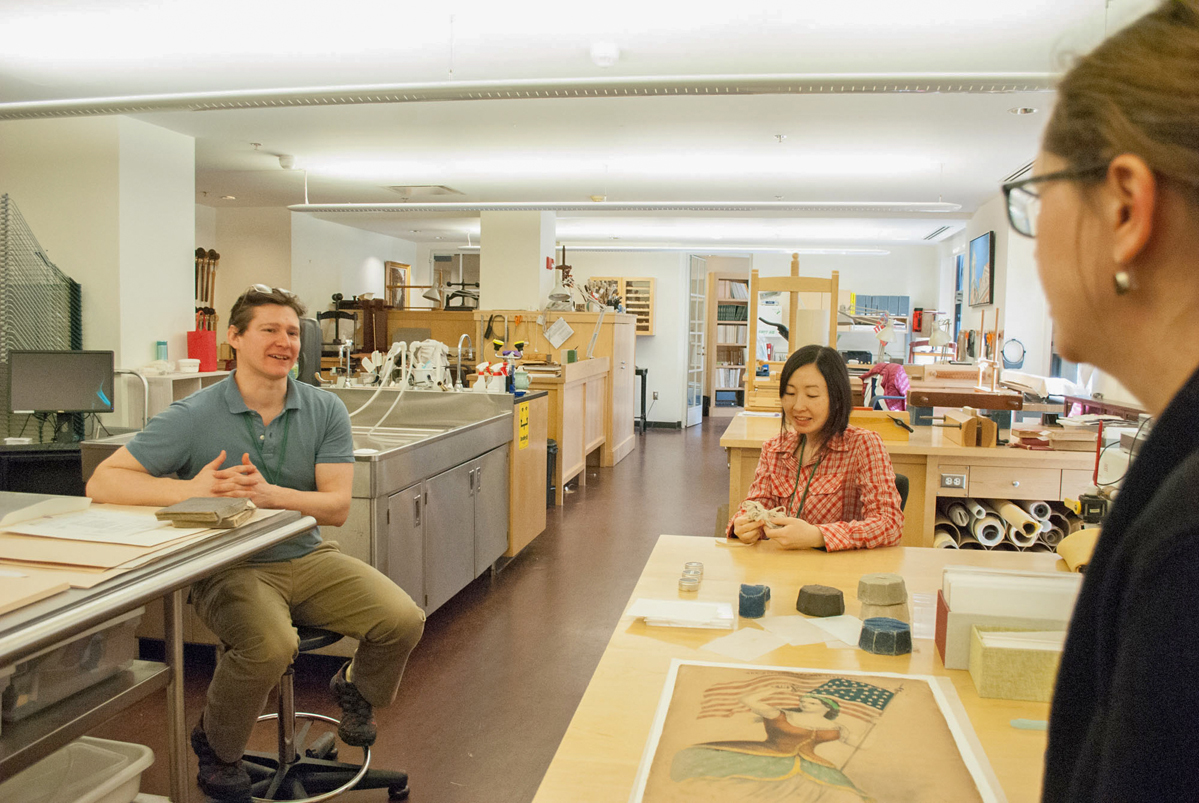

While the Athenaeum was founded in 1807, the conservation lab was more recently established in 1963. Still, the lab is one of the oldest of its kind. Walus, associate conservator Evan Knight, and research fellows Lauren Calcote and Liane Na’auao are tasked with the long-term preservation of the Athenaeum’s collections.

On any given day, Walus could be working with a poster from the Civil War, or rebinding a book that Paul Revere once held and read. On a Monday morning in March, she arranges the pages of a 200-year-old letter with her bare hands. One might envision a conservation as a sterile goggles-and-gloves-wearing profession, but Walus says gloves generally aren’t necessary.

“For the profession as a whole, we’ve found that we can actually do more damage with these clumsy cotton gloves than you would if you just had clean hands,” she says.

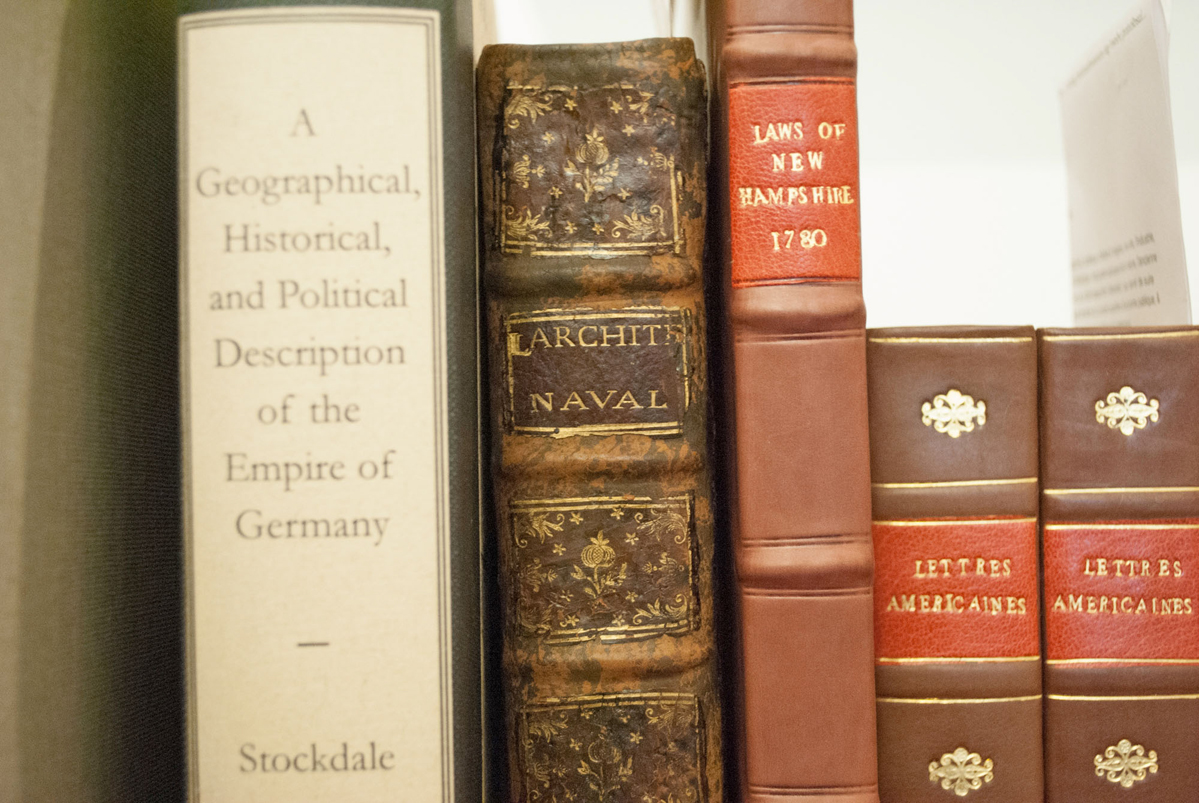

Around the 1,500-square-foot lab, the gloveless conservators could be preserving papers of the past in various ways. Books are rebound, recovered, and redecorated. Japanese paper, called washi, is used to mend tears and holes in old, brittle papers. Maps are prevented from further ripping with clear adhesive, and small boxes are built to cover certain books.

On that same March morning, Calcote presses metallic designs into a leather book cover. She uses ornamental tools to decorate the cover in a style authentic to the book’s time period. Similarly, Walus constructs a book box for an antique book, measuring and cutting on another work table.

Meanwhile, Na’auao assembles a wheat starch paste near the lab’s sink. She mixes the ingredients in a machine called a Cook N’ Stir, a kitchen appliance that’s more than ten years old.

“It’s a small field so there aren’t many people making materials or equipment specifically for conservation. A lot of times we’re adopting from other fields,” says Walus.

“The Cook N’ Stir is really meant to make sauces—those fancy French sauces that you need to stir and stir and stir or it’s not going to come out right.”

But the Cook N’ Stir is not nearly the oldest tool used in the lab. Huge metal machines weighing upward of 1,000 pounds can be found in different corners of the room. A metal contraption called a job backer sits near the entryway—it holds a book in place while being hand-bound. A 1900s standing bookbinding press occupies the back wall of the lab, and a large board sheer manufactured in Worcester, Massachusetts, more than 100 years ago is situated outside of Walus’s office.

The dated machines are the dominant features of the lab, where there’s a surprisingly refreshing lack of screens. In bookbinding and preservation, old tools reign supreme.

“That’s sort of the nature of the Athenaeum’s collections. It’s an old collection, for the most part, and we’re using the tools that would have been used to make these things originally,” says Walus.

“The lab is set up as this sort of blend between old technology and new technology. What we need to do the job is the old technology. The sort of innovative thing that we’re doing is bringing new materials into our work, but also at the same time, (we use) tools that have stood the test of time and we know they’re not going to harm the materials that we’re trying to preserve.”

Through her work, Walus explains she’s upholding a historical authenticity.

“I think anybody who does this kind of work is keeping a certain number of various traditions alive. That’s a good thing, too,” she says. “We’re trained in history and the technology of how these things have been made.”

“And it’s a very long tradition,” laughs Walus. “About 2,000 years old.”