Bulger Victim’s Kin: ‘I Will Never Get Justice’

As the first day of the Whitey Bulger trial wrapped up at the Moakley Courthouse on Wednesday afternoon, Michael Patrick MacDonald, who grew up in Southie the 1970s under the shadow Bulger cast during his prime, recounted some of the details he didn’t expect to hear this soon.

“They sort of acknowledged that in some way he oversaw the drug trade. Bulger has always tried to skirt that accusation—for years people insisted he kept drugs out of South Boston. Now that he has returned from the dead, he is not saying that,” said MacDonald, author of the book All Souls: A Family Story From Southie, which details his siblings’ ties to the notorious gangster and what growing up in the Old Colony projects was like.

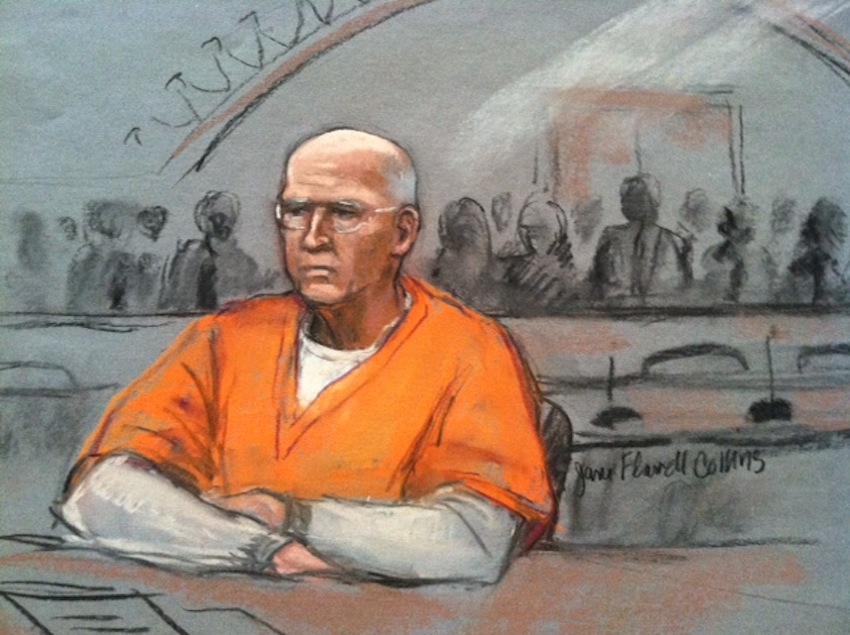

Bulger’s lawyers and federal prosecutors had the chance to offer opening statements on Wednesday, two days after originally planned, following a daunting jury selection process that required sifting through hundreds of potential people from the jury pool. Assistant U.S. Attorney Brian Kelly spent roughly one hour outlining some of the alleged offenses that were a part of Bulger’s crime-spree syndicate, skimming the surface of the 32 charges that are the basis of what’s undoubtedly going to be a months-long trial. During that testimony, Kelly touched upon key points that pinned Bulger to the drug ring beset on the neighborhood he once called home.

For MacDonald, a sense of some relief came from finally hearing from both the prosecution and the defense that there was a connection between Bulger and the rampant drug use that plagued one of Boston’s poorest neighborhoods in the 1970s. “When my book came out in 1999, and I made those claims [about Bulger’s connection to the drug trade], I had to leave town,” said MacDonald, who said he received death threats for insinuating the prospect “But now with everyone saying what they want about the trial, and about the crimes, it was amazing to hear that confirmed, all that stuff I wrote 13 years ago. It’s a relief that, after all these years, that it’s not in dispute.”

For MacDonald, what’s still in dispute after all these years are the circumstances surrounding the deaths of his brothers, Frankie and Kevin, who were each found dead after working odd jobs with some of Bulger’s associates.

MacDonald said Kevin, who the family sort of expected to wind up traveling down a troubled path, even had Bulger as his witness during an impromptu wedding ceremony with a Justice of the Peace in Boston. Kevin was found hanged in a prison cell in March 1985, and MacDonald said he suspects Kevin’s death stemmed from fear that his brother would speak about acts he committed under Bulger’s wing in exchange for a shorter sentence.

Frankie, a four-time Golden Gloves championship boxer with a bright future, surprised everyone in the neighborhood, MacDonald said, after he was shot and killed in July 1984, during a botched bank robbery that may have been orchestrated by criminals in Bulger’s circle. Some of Frankie’s biggest fans, who also worked his corner in the boxing ring, were Bulger’s closest associates.

MacDonald said their deaths, just a year apart, occurred during “the height of the Bulger years.”

While some preliminary details have come to light just one day into the trial, MacDonald says what the court proceedings won’t do is provide justice for the “hundreds upon hundreds” of lives that were impacted by the trickle-down of drug use and political corruption through generations of Southie families. “[My brothers] were just a small part of the very large population of Southie residents whose lives were lost, or maimed, in those years dominated by Whitey Bulger’s reign,” said MacDonald.

An eye for an eye won’t make it better:

As the trial is focused on 19 murders that Bulger allegedly committed or ordered to be carried out, some of those charges Bulger has vehemently denied, citing a so-called “code of honor.” One such instance is the 1981 death of Debra Davis, a former girlfriend of Bulger’s right-hand man Steve Flemmi. According to testimony Flemmi gave when he stood trial for his own crimes, Bulger insisted the pair kill Davis, calling her a flight risk who knew too much about their operations. He testified that it was Bulger who strangled the woman before the pair dumped her body in a marsh.

In letters recently obtained by the Globe, Bulger wrote about his innocence in Davis’ death, saying it went against his ideals to kill women. But in an interview, Steve Davis, brother of the victim, called it “bullshit,” saying it was just another ruse from a known swindler.

“You can’t go back. There is no taking it back,” Davis said. “And now he is trying to justify that he didn’t do it, and that’s bullshit. I want my sister’s death to mean something to me, that there was justice. I’m an eye-for-an-eye type of guy. If I can’t beat you with my hands, I’ll do it a dirty way. I’ll never get even with this, though.”

If Bulger were let off the hook from his alleged role in Davis’ murder, Davis isn’t sure he’d know how to handle it. “I can’t see him beating my sister’s murder. There is no way in the world. I couldn’t even … I couldn’t put that thought in my head. It would be too much to digest,” he said.

Like MacDonald, Davis believes Bulger’s role in running an elaborate crime ring only touches the surface of a deeper, more corrupt system that stretched from the halls of Beacon Hill to the projects of South Boston. “The politician ties he has in Massachusetts are stronger than any other gang in the world. You are talking—this guy, his brother, [former Senate President] Billy Bulger, put a lot of people in office and to work, and appointed a lot of people in the courts. They should be going after him, too,” said Davis, sounding agitated. “The full part of justice won’t be served [with just Whitey]—I want his brother Billy. I want Billy more than him.”

According to MacDonald, the trial could expose some of those “truths” and drudge up information that could show how so much blatant crime went unpunished, including within the FBI, shedding light on a culture in South Boston that was forced into silence by Bulger and “his helpers in high places.” Bulger has been fingered as federal informant who allegedly worked closely with former FBI agent John Connolly, something Bulger’s lawyers now expressly deny. Connolly is currently serving a 10-year jail sentence for his relationship with both Bulger and Flemmi. In May 2002, a federal jury convicted him of racketeering and obstruction of justice, and for tipping the two off to their secret indictment in 1994. When Bulger learned of the pending indictment, he fled Boston, spending 16 years on the lam.

“All the political officials knew what was going on … I think that Billy absolutely knew what was going on … we were an incredibly connected community,” said MacDonald. “We were incredibly informed about everything going on in the streets, nothing could go under the radar, and I can’t imagine that Billy Bulger was in the dark while my little brothers, who were 9 and 10, knew what was going on.”

But regardless of the things that can’t be seen on a 32-count indictment—and no matter the outcome of the trial—Davis said he will be there every single day, staked out in the same room as his sister’s alleged killer, waiting, patiently, for his day in court. “He’s not going to live long. I know it. So no matter what happens, you are giving him a death sentence anyway,” he said.