The Life in Our Stars

Astronomers, Seager explains, probably won’t be able to use the transit method to study the atmosphere of a true Earth twin, because such a planet would be simply too small, compared with its star, to detect. Instead, they’ll need to take a picture of the planet directly. And to do that, they’ll first have to block the otherwise overwhelming glare of the star. Thus Seager’s latest project: the development of that giant star shade, one that can hover in front of a space telescope as it peers out at planets.

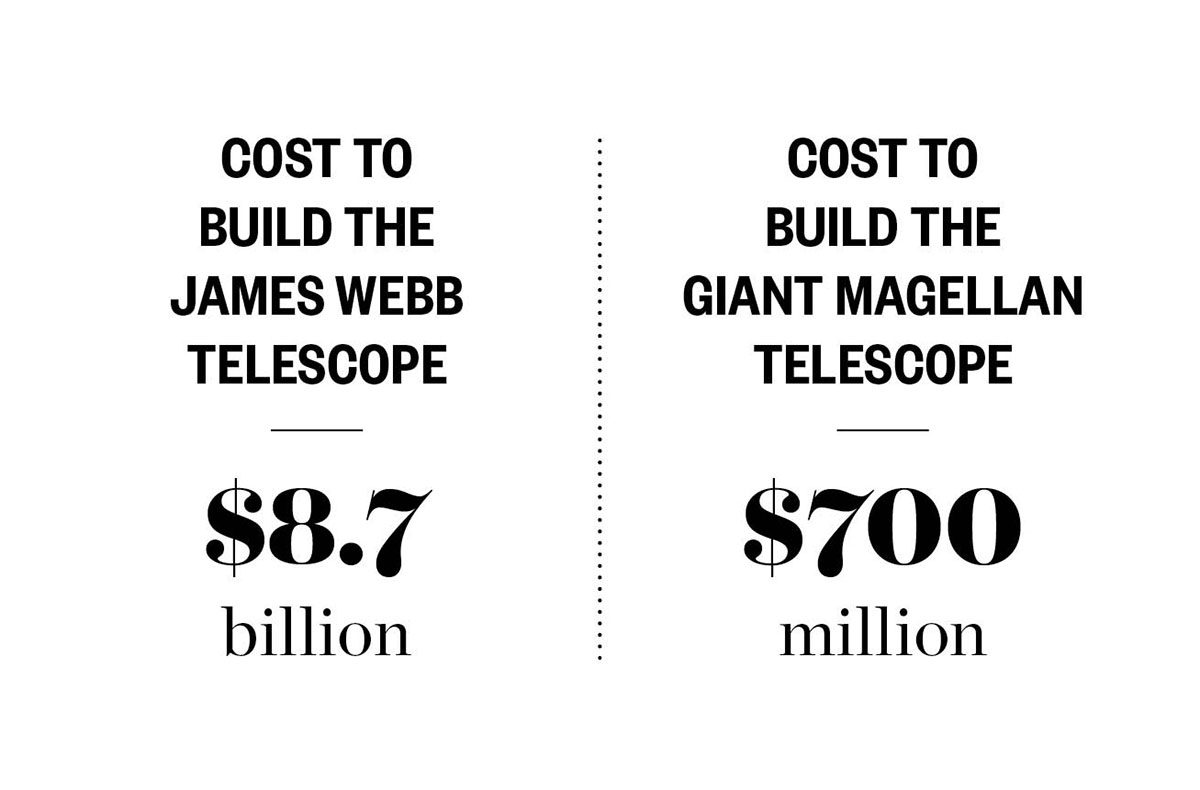

One of Seager’s MIT colleagues, Kerri Cahoy, is working on a version that would fit inside the space telescope when it’s launched, paired with tiny mirrors to help focus the planet’s tiny slivers of light. Once again, Seager is designing technologies for missions that don’t yet exist. She’s already planning for more-advanced exoplanet-hunting instruments that will follow the James Webb telescope. There’s one called the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) that’s already moving through NASA’s lengthy mission-vetting process. The technical challenges are huge. It’s not rocket science: It’s much harder.

“The star shade and telescope have to be aligned, just so, at tens of thousands of kilometers apart,” Seager explained in her 2013 Cambridge TEDx talk. “That’s like asking a friend to hold up a dime at 5 miles away and line up right with you.”

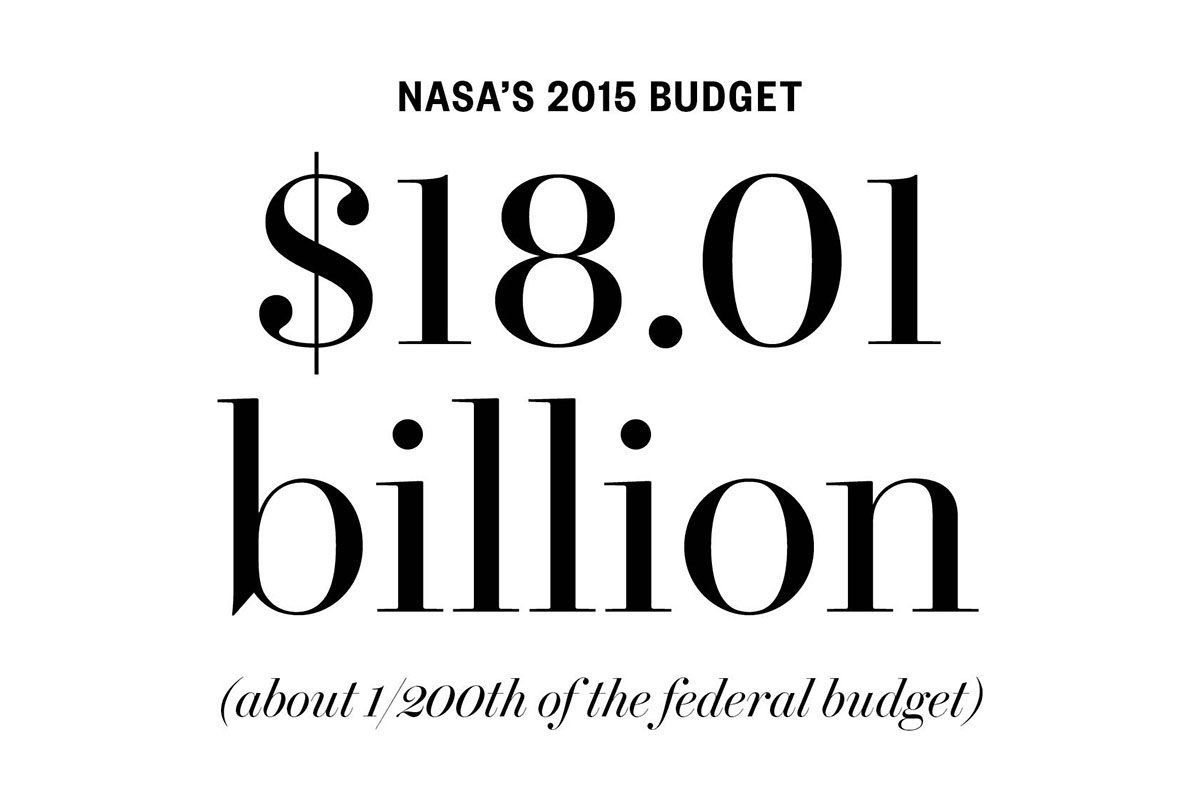

There are still huge budgetary hurdles. For the past several years, NASA’s total budget has hovered around $17 or $18 billion—or about half a percent of the federal budget. With $18 trillion in national debt, there are plenty of people who question the wisdom of spending billions to explore space. Every year, the space agency makes its case to Congress and the public on the relevance of its work. An online video accompanying the agency’s 2015 budget proposal, for example, included a not-so-subtle reminder that only NASA could save the Earth from a world-destroying asteroid. The Congressional committee that keeps tabs on NASA includes Congressman Paul Broun, a Republican from Georgia who has described evolution, and the big bang theory, as “lies straight from the pit of hell.” In spite of him, Congress allocated $18 billion to NASA for 2015, a 2 percent increase from 2014 and $500 million more than the agency had requested.

In June 2013, Seager was the keynote speaker at an amateur weekend astronomy event in Toronto, put on by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada—the same group that hosted the star party where, as a girl, Seager had first fallen in love with the night sky. There she met Charles Darrow, then president of the RASC’s Toronto chapter. They struck up a friendship and started dating in early 2014.

“It’s a long story,” Seager tells me with a laugh. “But he’s my fiancé. I’m getting married again now. It’s so cool having him around. It’s like being a newlywed.”

Last summer, in the July issue of Astrophysical Journal, Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb and his colleagues suggested that we could find alien civilizations, or at least their remnants, by looking for industrial pollutants in the atmospheres of exoplanets, rather than just biomarkers like oxygen.

On a chilly fall evening, I drove out to visit Loeb at his home in Lexington. We went outside into the middle of his quiet street and looked up, something Loeb does most every clear night.

“When the moon is not bright, you can sort of see the stars of the Milky Way,” Loeb said. On that evening, only the brightest stars were out, but Loeb walked over to some birch trees that blocked the glare of a neighbor’s house lights, to give us a better view. “You know, the Milky Way is not standing still, relative to the universe. It’s in motion, and I think of it like a giant spaceship that is full of lights,” he continued. “And the basic question is, Are there other passengers on this giant spaceship streaming through space?”

After a pause, I asked him, “What do you want the answer to be?”

“I very much hope we’ll find evidence for other intelligent civilizations,” he said. “That would make the universe more fascinating and unpredictable.” If it happened, Loeb said, “it would be the biggest thrill of my life. The prejudice people have—that we’re alone, because we’re special—that will go away. It will perhaps lead people to realize that we are part of the same team. It makes no sense for us to fight with each other over territorial boundaries on this two-dimensional surface of the Earth. There is a much bigger volume out there, and we’d better stick together, because in the big scheme of things, we have the same fate. In astronomical terms, if the Sun dies, we all have to move somewhere else.”

Today, about one-third of the applicants to Harvard’s graduate program in astronomy declare an interest in studying exoplanets, Charbonneau points out. This next generation of scientists has never known a universe without other worlds orbiting other stars.

They have already begun to take up the task of looking, meticulously, for signs of life. It could be as close to us as Mars—hidden beneath its sterile surface—or on Jupiter’s moon, Europa, where scientists believe a liquid ocean hides beneath an icy crust. Or it could go the other way. Maybe in the next 50 years, Charbonneau says, we’ll find hundreds of Earthlike planets, and “extensively study the 10 closest, Earthiest ones, and find nothing.”

Charbonneau hopes that’s not the case: “I started my career as an astronomer, and my hope is that in 20 years, I’ll end up as a biologist…to study the biology on other planets.”

Loeb says, “We make progress by showing how many of the things we assumed were true were actually wrong. Unless you put yourself in a position where you may be wrong, you don’t learn about reality. It is the essence of science.”